Ælfwald Of East Anglia

After returning from exile, Æthelbald of Mercia succeeded Coelred and afterwards endowed the church at Crowland. Ælfwald's friendly stance towards Æthelbald helped to maintain peaceful relations with his more powerful neighbour. The Life of Guthlac, which includes information about Æthelbald during his period of exile at Crowland, is dedicated to Ælfwald. Later versions of the Life reveal the high quality of written Old English produced in East Anglia during Ælfwald's reign. He was a literate and devoutly Christian king: his letter written to Boniface in around 747 reveals his diplomatic skills and gives a rare glimpse into the life of a ruler who is otherwise shrouded in obscurity.

Pedigree

The East Anglian pedigree in the Anglian collection brings the descent down to Ælfwald, indicating that it was compiled during his reign, possibly by around 726. Showing Ælfwald as son of Ealdwulf, the pedigree continues back through Ethelric, Eni, Tytla, Wuffa, Wehha, Wilhelm, Hryp, Hrothmund, Trygil, Tyttman and Caser (Caesar) to Woden. The Historia Brittonum, which was probably compiled in the early 9th century, also has a version (the de ortu regum Estanglorum) in descending order, showing: "Woden genuit ('begat') Casser, who begat Titinon, who begat Trigil, who begat Rodmunt, who begat Rippan, who begat Guillem Guechan. He first ruled in Britain over the race of East Angles. Guecha begat Guffa, who begat Tydil, who begat Ecni, who begat Edric, who begat Aldul, who begat Elric". It is not certain whether the last name, Elric, is a mistake for Ælfwald or is referring to a different individual.

Reign

Accession

At Ælfwald's accession in 713, Ceolred of Mercia had dominion over both Lindsey and Essex. Ælfwald's sister Ecgburgh was, possibly, the same as abbess Egburg at Repton in Derbyshire and Ælfwald's upbringing was undoubtedly Christian in nature.

The following family tree shows the descendants of Eni, who was the paternal grandfather of Ælfwald. The kings of East Anglia, Kent and Mercia are coloured green, blue and red respectively:

| Eni of East Anglia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Anna | Saewara | Æthelhere | Æthelwold | Æthelric | Hereswith | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Eorcenberht of Kent | Seaxburh | Æthelthryth | Æthelburh | Jurmin | Ealdwulf | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ermenilda | Wulfhere of Mercia | Ercongota | Ecgberht | Hlothhere | Ælfwald | Ecgburgh | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Coenred | Coelred of Mercia | Werburh | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Felix's 'Life of Guthlac'

Ceolred of Mercia's appropriation of monastic assets during his reign created disaffection amongst the Mercians. He persecuted a distant cousin, Æthelbald, the grandson of Penda's brother Eowa. Æthelbald was driven to take refuge deep in the Fens at Crowland, where Guthlac, another descendant of the Mercian royal house, was living as a hermit. When Guthlac died in 714, Ælfwald's sister Ecgburgh provided a stone coffin for his burial. Ceolred died in 716, blaspheming and insane, according to his chroniclers. Penda's line became extinct (or disempowered) and Æthelbald emerged as king of Mercia.

Æthelbald lived until 757 and carried Mercian power to a new height. His debt to Crowland was not forgotten: soon after his accession he richly endowed a new church on the site where Guthlac had lived as a hermit. The first Life of Guthlac, written by the monk Felix, appeared soon after Guthlac's death. Nothing is known about Felix, although Bertram Colgrave has observed that he was a good scholar who evidently had access to works by Bede and Aldhelm, to a Life of Saint Fursey and Latin works by Saint Jerome, Saint Athanasius and Gregory the Great. Felix was either an East Anglian or was living in the kingdom when he wrote the book, which was written at the request of Ælfwald. In the Life, Felix portrays Æthelbald's exile at Crowland and asserts Ælfwald's right to rule in East Anglia. Two Old English verse versions of the Life drawn on the work of Felix were written, which show the vigour of vernacular heroic and elegiac modes in Ælfwald's kingdom.

Sam Newton has proposed that the Old English heroic poem Beowulf has its origins in Ælfwald's East Anglia.

The king's bishops

Æcci held the East Anglian see of Dommoc, following its division in about 673, and during Ealdwulf's reign Æscwulf succeeded Æcci. At the Council of Clofeshoh in 716, Heardred attended as Bishop of Dommoc, while Nothberht was present as Bishop of Elmham, having succeeded Baduwine.

During the 720s, Cuthwine became bishop of Dommoc. Cuthwine was known to Bede and is known to have travelled to Rome, returning with a number of illuminated manuscripts, including Life and Labours of Saint Paul: his library also included Prosper Tiro's Epigrammata and Sedulius' Carmen Pachale. According to Bede, Ealdbeorht I was Bishop of Dommoc and Headulacus Bishop of Elmham in 731, but by 746 or 747, Heardred (II) had replaced Aldberct.

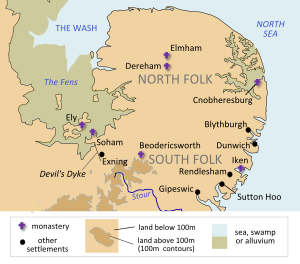

The development of the port at Gipeswic

Ipswich was the first East Anglian town to be created by the Anglo-Saxons, predating other new towns such as Norwich by a century. Excavation work at Ipswich has revealed that the town expanded out to become 50 hectares (120 acres) in size during Ælfwald's reign, when it was known as Gipeswic. It is generally considered that Gipeswic, as the trade capital of Ælfwald's kingdom, developed under the king's patronage.

A rectangular grid of streets linked the earlier quayside town northwards to an ancient trackway that ran eastwards. The quay at Gipeswic also continued to develop in a form that was similar to the quayside at Dorestad, south of the continental town of Utrecht, which was perhaps its principal trading partner. Gipeswic's street grid, parts of which have survived, was subdivided into rectangular plots or insulae and new houses were built directly adjacent to metalled roads. The town's pottery industry, producing what has been known since the 1950s as 'Ipswich ware', gained its full importance at around this time.

The former church dedication to Saint Mildred is one that can be dated to the 740s, when Mildred's relics were translated at Minster-in-Thanet by her successor abbess Eadburh.

Coinage

The coins of Ælfwald's reign are amongst the earliest that were minted in East Anglia. The coinage of silver pennies known as sceattas expanded in his time and several types are attributed to East Anglian production. Most of them fall into two main groups, known as the 'Q' and 'R' series. Neither group bears a royal name or title and the authority by which they were issued cannot not established. The 'Q' series, which has some Northumbrian affinities, is most densely distributed in western East Anglia, along the Fen edge between the Wash and Cambridge. The R series, with bust and standard, derived from earlier Kentish types, is more densely distributed in central and eastern East Anglia, including the Ipswich area. According to Michael Metcalf, the 'R' series was also East Anglian, being minted at Gipeswic.

Letter to Boniface

"To the most glorious lord, deserving of every honour and reverence. Archbishop Boniface, Ælfwald, by God's gift endowed with kingly sway over the Angles, and the whole abbey with all the brotherhood of the servants of God in our province who invoke Him, throned on high, with prayers night and day for the safety of the churches, greetings in God who rewards all.

First of all we would have thee know, beloved, how gratefully we learn that our weakness has been commended to your holy prayers; so that, whatever your benignity by the inspiration of God commanded concerning the offering of masses and the continuous prayers, we may attempt with devoted mind to fulfil. Your name will be remembered perpetually in the seven offices of our monasteries; by the number seven perfection is often designated. Wherefore, since this has been well ordered and by God's help the rules for the soul have been duly determined and the state of the inner man is provided for, the external aids of earthly substance, which by the bounty of God have been placed in our power, we wish to be at your will and command, on condition, however, that through your loving kindness you have the assistance of your prayers given to us without ceasing in the churches of God. And just as the purpose of God willed thee to become a shepherd over His people, so we long to feel in thee our patron. The names of the dead and of those who enter upon the way of all flesh, will be brought forward on both sides, as the season of the year demands, that the God of Gods and the Lord of Lords, who willed to place you in authority over bishops, may deign to bring His people through you to a knowledge of the One in Three, the Three in One.

Farewell, until you pass the happy goal.

Besides, holy father, we would have thee know that we have sent across the bearer of the present letter with a devout intention; just as we have found him faithful to you, so wilt thou find that he speaks the truth in anything relating to us."

A letter from Ælfwald to Boniface, the leader of the English continental mission, has survived. It was written at some time between 742 and 749 and is one of the few surviving documents from the period that relate the ecclesiastical history of East Anglia.

The letter, which is a response to Boniface who had requested his support, reveals Ælfwald's sound understanding of Latin. Ælfwald's letter reassures Boniface that his name was being remembered by the East Angles: it contains an offer to exchange the names of their dead, so that mutual prayers could be read for them. According to Richard Hoggett, a phrase in the letter, "in septenis monasteriorum nostorum sinaxis", has been interpreted incorrectly by historians to imply that there were at the time seven monasteries in Ælfwald's kingdom in which prayers were being read, a theory which has proved difficult for scholars to explain. Hoggett argues that the words in the phrase refer to the number of times that the monks offered praise during the monastic day and not to the number of monasteries then in existence. He points out that this interpretation was published by Haddan and Stubbs as long ago as 1869.

Death

Ælfwald died in 749. It is not known whether he left an immediate heir. After his death, according to mediaeval sources, East Anglia was divided among three kings, under circumstances that are not clear.

Notes

- ^ For a detailed discussion of Felix's writing style and the works that he would have been familiar with and that would have influenced him, see the introductory chapter in Felix's Life of Saint Guthlac, by Bertram Colgrave.

References

- ^ Dumville, The Anglian Collection, pp. 23-50.

- ^ Nennius, in Giles (ed.), Old English Chronicles, p. 412.

- ^ Royal Historical Society, Guides and Handbooks, Issue 2, p. 20.

- ^ Yorke, Kings, p, 63.

- ^ Fyrde et al, Handbook of British Chronology, pp. 1-25.

- ^ Eckenstein, Lina (1963) [1896]. Woman under Monasticism. New York: Russell and Russell. pp. 109, 125.

- ^ Fryde et al, Handbook of British Chronology, p. 9.

- ^ Brown and Farr, Mercia, p. 70.

- ^ Colgrave, Life of Guthlac, p. 5.

- ^ Colgrave, Life of Guthlac, p. 6.

- ^ Colgrave, Life of Guthlac, p. 147.

- ^ Colgrave, Life of Guthlac, p. 7.

- ^ Hunter Blair, Roman Britain, p. 168.

- ^ Plunkett, Suffolk, p. 144.

- ^ Colgrave, Life of Saint Guthlac, pp. 15-16.

- ^ Colgrave, Life of Saint Guthlac, pp. 16-18.

- ^ Colgrave, Felix's Life of Saint Guthlac, p. 61.

- ^ Newton, The Origins of Beowulf, p. 133.

- ^ Fyrde et al, Handbook of British Chronology, p. 216.

- ^ Plunkett, Suffolk in Anglo-Saxon Times, p. 144.

- ^ Plunkett, Suffolk in Anglo-Saxon Times, p. 146.

- ^ Fryde et al, Handbook of British Chronology, p. 216.

- ^ Wade, Ipswich, p. 1,

- ^ Wade, Ipswich, p. 2.

- ^ Allen, Ipswich Borough Archives, p. xvii.

- ^ Yorke, Kings, pp. 65-66

- ^ Plunkett, Suffolk in Anglo-Saxon Times, p. 149.

- ^ Russo, Town Origins and Development in Early England, c.400-950 A.D., p. 172.

- ^ Plunkett, Suffolk in Anglo-Saxon Times, pp. 149-150.

- ^ Wade, Ipswich, p. 3.

- ^ Yorke, Kings, p. 66.

- ^ Plunkett, Suffolk in Anglo-Saxon Times, p. 148.

- ^ Newman, in Two Decades of Discovery, p. 18.

- ^ Metcalf, Two Decades of Discovery, p. 10.

- ^ Kylie, English Correspondence, pp. 152-153.

- ^ Hoggett, The Archaeology of the East Anglian Conversion, p. 34.

- ^ Hoggett, East Anglian Conversion, pp. 34-35.

- ^ Haddan, Stubbs, Ecclesiastical Documents, pp. 152-153.

- ^ Plunkett, Suffolk, p. 155.

- ^ Kirby, The Earliest English Kings, p. 115.

Sources

- Colgrave, B., ed. (2007). Felix's Life of Guthlac. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-31386-5.

- Dumville, D. N. (1976). "The Anglian Collection of Royal Genealogies and Regnal Lists". Anglo-Saxon England. 5. Cambridge Journals Online: 23–50. doi:10.1017/S0263675100000764. S2CID 162877617.

- Brown, Michelle P.; Farr, Carol Ann (2001). Mercia: an Anglo-Saxon Kingdom in Europe. Leicester University Press. ISBN 0-8264-7765-8.

- Fryde, E. B.; Greenway, D. E.; Porter, S.; Roy, I. (1986). Handbook of British Chronology (3rd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-56350-X.

- Hoggett, Richard (2010). The Archaeology of the East Anglian Conversion. Woodbridge, UK: The Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-595-0.

- Haddan, Arthur West; Stubbs, William (1869). Councils and Ecclesiastical Documents relating to Great Britain and Ireland. Vol. 3. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 387–388. OCLC 1317490. Retrieved 23 August 2011.

- Hunter Blair, Peter (1966). Roman Britain and Early England: 55 B.C. - A.D. 871. W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-00361-2.

- Kirby, D. P. (2000). The Earliest English Kings. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-4152-4211-8.

- Kylie, Edward (1911). English Correspondence, Being for the Most Part Letters Exchanged Between the Apostle of the Germans and his English Friends. London: Chatto & Windus.

- Metcalf, Michael (2008). "Sceattas: Twenty-One Years of Progress". In Abramson, Tony (ed.). Two Decades of Discovery. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-371-0.

- Nennius (1906) [9th century]. "Historia Brittonum". In Giles, J. A. (ed.). Old English Chronicles. London: George Bell. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- Newman, John (2008). "Sceattas in East Anglia: An Archaeological Perspective". In Abramson, Tony (ed.). Two Decades of Discovery. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-371-0.

- Plunkett, Steven (2005). Suffolk in Anglo-Saxon Times. Stroud: Tempus. ISBN 0-7524-3139-0.

- Russo, Daniel G. (1998). Town Origins and Development in Early England, c.400-950 A.D. Westport, U.S.A.: Greenwood. ISBN 0-313-30079-8.

- Wade, Keith (2001). "Gipeswic: East Anglia's first economic capital, 600-1066". Ipswich from the First to the Third Millennium. Ipswich: Wolsey Press. ISBN 0-9507328-1-8.

- Yorke, Barbara (2002). Kings and Kingdoms of Early Anglo-Saxon England. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-16639-X.

External links

- Ælfwald 6 at Prosopography of Anglo-Saxon England

- A translation into both modern and Old English of Felix's Vita Sancti Guthlaci ('Life of St Guthlac') by Charles Goodwin (1848), from the Internet Archive.