Anisoptera

Dragonflies can be mistaken for the closely related damselflies, which make up the other odonatan infraorder (Zygoptera) and are similar in body plan, though usually lighter in build; however, the wings of most dragonflies are held flat and away from the body, while damselflies hold their wings folded at rest, along or above the abdomen. Dragonflies are agile fliers, while damselflies have a weaker, fluttery flight. Dragonflies make use of motion camouflage when attacking prey or rivals.

Dragonflies are predatory insects, both in their aquatic nymphal stage (also known as "naiads") and as adults. In some species, the nymphal stage lasts up to five years, and the adult stage may be as long as 10 weeks, but most species have an adult lifespan in the order of five weeks or less, and some survive for only a few days. They are fast, agile fliers capable of highly accurate aerial ambush, sometimes migrating across oceans, and often live near water. They have a uniquely complex mode of reproduction involving indirect insemination, delayed fertilisation, and sperm competition. During mating, the male grasps the female at the back of the head, and the female curls her abdomen under her body to pick up sperm from the male's secondary genitalia at the front of his abdomen, forming the "heart" or "wheel" posture.

Fossils of very large dragonfly-like insects, sometimes called griffinflies, are found from 325 million years ago (Mya) in Upper Carboniferous rocks; these had wingspans up to about 750 mm (30 in), though they were only distant relatives, not true dragonflies which first appeared during the Early Jurassic.

Dragonflies are represented in human culture on artefacts such as pottery, rock paintings, statues, and Art Nouveau jewellery. They are used in traditional medicine in Japan and China, and caught for food in Indonesia. They are symbols of courage, strength, and happiness in Japan, but seen as sinister in European folklore. Their bright colours and agile flight are admired in the poetry of Lord Tennyson and the prose of H. E. Bates.

Etymology

The infraorder Anisoptera comes from Greek ἄνισος anisos "unequal" and πτερόν pteron "wing" because dragonflies' hindwings are broader than their forewings.

Evolution

Dragonflies and their relatives are similar in structure to an ancient group, the Meganisoptera or griffinflies, from the 325 Mya Upper Carboniferous of Europe, a group that included one of the largest insects that ever lived, Meganeuropsis permiana from the Early Permian, with a wingspan around 750 mm (30 in). The Protanisoptera, another ancestral group that lacks certain wing-vein characters found in modern Odonata, lived in the Permian.

Anisoptera first appeared during the Toarcian age of the Early Jurassic, and the crown group developed in the Middle Jurassic. They retain some traits of their distant predecessors, and are in a group known as the Palaeoptera, meaning 'ancient-winged'. Like the gigantic griffinflies, dragonflies lack the ability to fold their wings up against their bodies in the way modern insects do, although some evolved their own different way to do so. The forerunners of modern Odonata are included in a clade called the Panodonata, which include the basal Zygoptera (damselflies) and the Anisoptera (true dragonflies). Today, some 3,000 species are extant around the world.

The relationships of anisopteran families are not fully resolved as of 2021, but all the families are monophyletic except the Corduliidae, and the Austropetaliidae are sister to the Aeshnoidea:

| Anisoptera |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Distribution and diversity

About 3,012 species of dragonflies were known in 2010; these are classified into 348 genera in 11 families. The distribution of diversity within the biogeographical regions are summarized below (the world numbers are not ordinary totals, as overlaps in species occur).

| Family | Indomalaya | Neotropical | Australasian | Afrotropical | Palaearctic | Nearctic | Pacific | World |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aeshnidae | 149 | 129 | 78 | 44 | 58 | 40 | 13 | 456 |

| Austropetaliidae | 7 | 4 | 11 | |||||

| Petaluridae | 1 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 10 | |||

| Gomphidae | 364 | 277 | 42 | 152 | 127 | 101 | 980 | |

| Chlorogomphidae | 46 | 5 | 47 | |||||

| Cordulegastridae | 23 | 1 | 18 | 46 | ||||

| Neopetaliidae | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Corduliidae | 23 | 20 | 33 | 6 | 18 | 51 | 12 | 154 |

| Libellulidae | 192 | 354 | 184 | 251 | 120 | 105 | 31 | 1037 |

| Macromiidae | 50 | 2 | 17 | 37 | 7 | 10 | 125 | |

| Synthemistidae | 37 | 9 | 46 | |||||

| Incertae sedis | 37 | 24 | 21 | 15 | 2 | 99 |

Dragonflies live on every continent except Antarctica. In contrast to the damselflies (Zygoptera), which tend to have restricted distributions, some genera and species are spread across continents. For example, the blue-eyed darner Rhionaeschna multicolor lives all across North America, and in Central America; emperors Anax live throughout the Americas from as far north as Newfoundland to as far south as Bahia Blanca in Argentina, across Europe to central Asia, North Africa, and the Middle East. The globe skimmer Pantala flavescens is probably the most widespread dragonfly species in the world; it is cosmopolitan, occurring on all continents in the warmer regions. Most Anisoptera species are tropical, with far fewer species in temperate regions.

Some dragonflies, including libellulids and aeshnids, live in desert pools, for example in the Mojave Desert, where they are active in shade temperatures between 18 and 45 °C (64 and 113 °F); these insects were able to survive body temperatures above the thermal death point of insects of the same species in cooler places.

Dragonflies live from sea level up to the mountains, decreasing in species diversity with altitude. Their altitudinal limit is about 3700 m, represented by a species of Aeshna in the Pamirs.

Dragonflies become scarce at higher latitudes. They are not native to Iceland, but individuals are occasionally swept in by strong winds, including a Hemianax ephippiger native to North Africa, and an unidentified darter species. In Kamchatka, only a few species of dragonfly including the treeline emerald Somatochlora arctica and some aeshnids such as Aeshna subarctica are found, possibly because of the low temperature of the lakes there. The treeline emerald also lives in northern Alaska, within the Arctic Circle, making it the most northerly of all dragonflies.

General description

Dragonflies (suborder Anisoptera) are heavy-bodied, strong-flying insects that hold their wings horizontally both in flight and at rest. By contrast, damselflies (suborder Zygoptera) have slender bodies and fly more weakly; most species fold their wings over the abdomen when stationary, and the eyes are well separated on the sides of the head.

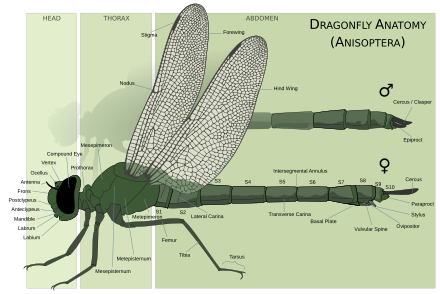

An adult dragonfly has three distinct segments, the head, thorax, and abdomen, as in all insects. It has a chitinous exoskeleton of hard plates held together with flexible membranes. The head is large with very short antennae. It is dominated by the two compound eyes, which cover most of its surface. The compound eyes are made up of ommatidia, the numbers being greater in the larger species. Aeshna interrupta has 22650 ommatidia of two varying sizes, 4500 being large. The facets facing downward tend to be smaller. Petalura gigantea has 23890 ommatidia of just one size. These facets provide complete vision in the frontal hemisphere of the dragonfly. The compound eyes meet at the top of the head (except in the Petaluridae and Gomphidae, as also in the genus Epiophlebia). Also, they have three simple eyes or ocelli. The mouthparts are adapted for biting with a toothed jaw; the flap-like labrum, at the front of the mouth, can be shot rapidly forward to catch prey. The head has a system for locking it in place that consists of muscles and small hairs on the back of the head that grip structures on the front of the first thoracic segment. This arrester system is unique to the Odonata, and is activated when feeding and during tandem flight.

The thorax consists of three segments as in all insects. The prothorax is small and flattened dorsally into a shield-like disc, which has two transverse ridges. The mesothorax and metathorax are fused into a rigid, box-like structure with internal bracing, and provide a robust attachment for the powerful wing muscles inside. The thorax bears two pairs of wings and three pairs of legs. The wings are long, veined, and membranous, narrower at the tip and wider at the base. The hindwings are broader than the forewings and the venation is different at the base. The veins carry haemolymph, which is analogous to blood in vertebrates, and carries out many similar functions, but which also serves a hydraulic function to expand the body between nymphal stages (instars) and to expand and stiffen the wings after the adult emerges from the final nymphal stage. The leading edge of each wing has a node where other veins join the marginal vein, and the wing is able to flex at this point. In most large species of dragonflies, the wings of females are shorter and broader than those of males. The legs are rarely used for walking, but are used to catch and hold prey, for perching, and for climbing on plants. Each has two short basal joints, two long joints, and a three-jointed foot, armed with a pair of claws. The long leg joints bear rows of spines, and in males, one row of spines on each front leg is modified to form an "eyebrush", for cleaning the surface of the compound eye.

The abdomen is long and slender and consists of 10 segments. Three terminal appendages are on segment 10; a pair of superiors (claspers) and an inferior. The second and third segments are enlarged, and in males, the underside of the second segment has a cleft, forming the secondary genitalia consisting of the lamina, hamule, genital lobe, and penis. There are remarkable variations in the presence and the form of the penis and the related structures, the flagellum, cornua, and genital lobes. Sperm is produced at the 9th segment, and is transferred to the secondary genitalia prior to mating. The male holds the female behind the head using a pair of claspers on the terminal segment. In females, the genital opening is on the underside of the eighth segment, and is covered by a simple flap (vulvar lamina) or an ovipositor, depending on species and the method of egg-laying. Dragonflies having simple flaps shed the eggs in water, mostly in flight. Dragonflies having ovipositors use them to puncture soft tissues of plants and place the eggs singly in each puncture they make.

Dragonfly nymphs vary in form with species, and are loosely classed into claspers, sprawlers, hiders, and burrowers. The first instar is known as a prolarva, a relatively inactive stage from which it quickly moults into the more active nymphal form. The general body plan is similar to that of an adult, but the nymph lacks wings and reproductive organs. The lower jaw has a huge, extensible labium, armed with hooks and spines, which is used for catching prey. This labium is folded under the body at rest and struck out at great speed by hydraulic pressure created by the abdominal muscles. Both damselfly and dragonfly nymphs ventilate the rectum, but just some damselfly nymphs have a rectal epithelium that is rich in trachea, relying mostly on three feathery external gills as their major source of respiration. Only dragonfly nymphs have internal gills, called a branchial chamber, located around the fourth and fifth abdominal segments. These internal gills consist originally of six longitudinal folds, each side supported by cross-folds. But this system has been modified in several families. Water is pumped in and out of the abdomen through an opening at the tip. The naiads of some clubtails (Gomphidae) that burrow into the sediment, have a snorkel-like tube at the end of the abdomen enabling them to draw in clean water while they are buried in mud. Naiads can forcefully expel a jet of water to propel themselves with great rapidity.

Coloration

Many adult dragonflies have brilliant iridescent or metallic colours produced by structural colouration, making them conspicuous in flight. Their overall coloration is often a combination of yellow, red, brown, and black pigments, with structural colours. Blues are typically created by microstructures in the cuticle that reflect blue light. Greens often combine a structural blue with a yellow pigment. Freshly emerged adults, known as tenerals, are often pale, and obtain their typical colours after a few days. Some have their bodies covered with a pale blue, waxy powderiness called pruinosity; it wears off when scraped during mating, leaving darker areas.

Some dragonflies, such as the green darner, Anax junius, have a noniridescent blue that is produced structurally by scatter from arrays of tiny spheres in the endoplasmic reticulum of epidermal cells underneath the cuticle.

The wings of dragonflies are generally clear, apart from the dark veins and pterostigmata. In the chasers (Libellulidae), however, many genera have areas of colour on the wings: for example, groundlings (Brachythemis) have brown bands on all four wings, while some scarlets (Crocothemis) and dropwings (Trithemis) have bright orange patches at the wing bases. Some aeshnids such as the brown hawker (Aeshna grandis) have translucent, pale yellow wings.

Dragonfly nymphs are usually a well-camouflaged blend of dull brown, green, and grey.

Biology

Ecology

Dragonflies and damselflies are predatory both in the aquatic nymphal and adult stages. Nymphs feed on a range of freshwater invertebrates and larger ones can prey on tadpoles and small fish. Naiads of one species, Phanogomphus militaris, may even act as parasites, feeding on the gills of gravid freshwater mussels. Adults capture insect prey in the air, making use of their acute vision and highly controlled flight.

The mating system of dragonflies is complex, and they are among the few insect groups that have a system of indirect sperm transfer along with sperm storage, delayed fertilisation, and sperm competition.

Adult males vigorously defend territories near water; these areas provide suitable habitat for the nymphs to develop, and for females to lay their eggs. Swarms of feeding adults aggregate to prey on swarming prey such as emerging flying ants or termites.

Dragonflies as a group occupy a considerable variety of habitats, but many species, and some families, have their own specific environmental requirements. Some species prefer flowing waters, while others prefer standing water. For example, the Gomphidae (clubtails) live in running water, and the Libellulidae (skimmers) live in still water. Some species live in temporary water pools and are capable of tolerating changes in water level, desiccation, and the resulting variations in temperature, but some genera such as Sympetrum (darters) have eggs and nymphs that can resist drought and are stimulated to grow rapidly in warm, shallow pools, also often benefiting from the absence of predators there. Vegetation and its characteristics including submerged, floating, emergent, or waterside are also important. Adults may require emergent or waterside plants to use as perches; others may need specific submerged or floating plants on which to lay eggs. Requirements may be highly specific, as in Aeshna viridis (green hawker), which lives in swamps with the water-soldier, Stratiotes aloides. The chemistry of the water, including its trophic status (degree of enrichment with nutrients) and pH can also affect its use by dragonflies. Most species need moderate conditions, not too eutrophic, not too acidic; a few species such as Sympetrum danae (black darter) and Libellula quadrimaculata (four-spotted chaser) prefer acidic waters such as peat bogs, while others such as Libellula fulva (scarce chaser) need slow-moving, eutrophic waters with reeds or similar waterside plants.

Behaviour

Many dragonflies, particularly males, are territorial. Some defend a territory against others of their own species, some against other species of dragonfly and a few against insects in unrelated groups. A particular perch may give a dragonfly a good view over an insect-rich feeding ground; males of many species such as the Pachydiplax longipennis (blue dasher) jostle other dragonflies to maintain the right to alight there. Defending a breeding territory is common among male dragonflies, especially in species that congregate around ponds. The territory contains desirable features such as a sunlit stretch of shallow water, a special plant species, or the preferred substrate for egg-laying. The territory may be small or large, depending on its quality, the time of day, and the number of competitors, and may be held for a few minutes or several hours. Dragonflies including Tramea lacerata (black saddlebags) may notice landmarks that assist in defining the boundaries of the territory. Landmarks may reduce the costs of territory establishment, or might serve as a spatial reference. Some dragonflies signal ownership with striking colours on the face, abdomen, legs, or wings. The Plathemis lydia (common whitetail) dashes towards an intruder holding its white abdomen aloft like a flag. Other dragonflies engage in aerial dogfights or high-speed chases. A female must mate with the territory holder before laying her eggs. There is also conflict between the males and females. Females may sometimes be harassed by males to the extent that it affects their normal activities including foraging and in some dimorphic species females have evolved multiple forms with some forms appearing deceptively like males. In some species females have evolved behavioural responses such as feigning death to escape the attention of males. Similarly, selection of habitat by adult dragonflies is not random, and terrestrial habitat patches may be held for up to 3 months. A species tightly linked to its birth site utilises a foraging area that is several orders of magnitude larger than the birth site.

Reproduction

Mating in dragonflies is a complex, precisely choreographed process. First, the male has to attract a female to his territory, continually driving off rival males. When he is ready to mate, he transfers a packet of sperm from his primary genital opening on segment 9, near the end of his abdomen, to his secondary genitalia on segments 2–3, near the base of his abdomen. The male then grasps the female by the head with the claspers at the end of his abdomen; the structure of the claspers varies between species, and may help to prevent interspecific mating. The pair flies in tandem with the male in front, typically perching on a twig or plant stem. The female then curls her abdomen downwards and forwards under her body to pick up the sperm from the male's secondary genitalia, while the male uses his "tail" claspers to grip the female behind the head: this distinctive posture is called the "heart" or "wheel"; the pair may also be described as being "in cop".

Egg-laying (ovipositing) involves not only the female darting over floating or waterside vegetation to deposit eggs on a suitable substrate, but also the male hovering above her or continuing to clasp her and flying in tandem. This behaviour following the transfer of sperm is termed as mate guarding and the guarding male attempts to increase the probability of his sperm fertilising eggs. Sexual selection with sperm competition occurs within the spermatheca of the female and sperm can remain viable for at least 12 days in some species. Females can fertilise their eggs using sperm from the spermatheca at any time. Males use their penis and associated genital structures to compress or scrape out sperm from previous matings; this activity takes up much of the time that a copulating pair remains in the heart posture. Flying in tandem has the advantage that less effort is needed by the female for flight and more can be expended on egg-laying, and when the female submerges to deposit eggs, the male may help to pull her out of the water.

Egg-laying takes two different forms depending on the species. The female in some families (Aeshnidae, Petaluridae) has a sharp-edged ovipositor with which she slits open a stem or leaf of a plant on or near the water, so she can push her eggs inside. In other families such as clubtails (Gomphidae), cruisers (Macromiidae), emeralds (Corduliidae), and skimmers (Libellulidae), the female lays eggs by tapping the surface of the water repeatedly with her abdomen, by shaking the eggs out of her abdomen as she flies along, or by placing the eggs on vegetation. In a few species, the eggs are laid on emergent plants above the water, and development is delayed until these have withered and become immersed.

Life cycle

Dragonflies are hemimetabolous insects; they do not have a pupal stage and undergo an incomplete metamorphosis with a series of nymphal stages from which the adult emerges. Eggs laid inside plant tissues are usually shaped like grains of rice, while other eggs are the size of a pinhead, ellipsoidal, or nearly spherical. A clutch may have as many as 1500 eggs, and they take about a week to hatch into aquatic nymphs or naiads which moult between six and 15 times (depending on species) as they grow. Most of a dragonfly's life is spent as a nymph, beneath the water's surface. The nymph extends its hinged labium (a toothed mouthpart similar to a lower mandible, which is sometimes termed as a "mask" as it is normally folded and held before the face) that can extend forward and retract rapidly to capture prey such as mosquito larvae, tadpoles, and small fish. They breathe through gills in their rectum, and can rapidly propel themselves by suddenly expelling water through the anus. Some naiads, such as the later stages of Antipodophlebia asthenes, hunt on land.

The nymph stage of dragonflies lasts up to five years in large species, and between two months and three years in smaller species. When the naiad is ready to metamorphose into an adult, it stops feeding and makes its way to the surface, generally at night. It remains stationary with its head out of the water, while its respiration system adapts to breathing air, then climbs up a reed or other emergent plant, and moults (ecdysis). Anchoring itself firmly in a vertical position with its claws, its exoskeleton begins to split at a weak spot behind the head. The adult dragonfly crawls out of its nymph exoskeleton, the exuvia, arching backwards when all but the tip of its abdomen is free, to allow its exoskeleton to harden. Curling back upwards, it completes its emergence, swallowing air, which plumps out its body, and pumping haemolymph into its wings, which causes them to expand to their full extent.

Dragonflies in temperate areas can be categorized into two groups: an early group and a later one. In any one area, individuals of a particular "spring species" emerge within a few days of each other. The springtime darner (Basiaeschna janata), for example, is suddenly very common in the spring, but disappears a few weeks later and is not seen again until the following year. By contrast, a "summer species" emerges over a period of weeks or months, later in the year. They may be seen on the wing for several months, but this may represent a whole series of individuals, with new adults hatching out as earlier ones complete their lifespans.

Sex ratios

The sex ratio of male to female dragonflies varies both temporally and spatially. Adult dragonflies have a high male-biased ratio at breeding habitats. The male-bias ratio has contributed partially to the females using different habitats to avoid male harassment. As seen in Hine's emerald dragonfly (Somatochlora hineana), male populations use wetland habitats, while females use dry meadows and marginal breeding habitats, only migrating to the wetlands to lay their eggs or to find mating partners. Unwanted mating is energetically costly for females because it affects the amount of time that they are able to spend foraging.

Flight

Dragonflies are powerful and agile fliers, capable of migrating across the sea, moving in any direction, and changing direction suddenly. In flight, the adult dragonfly can propel itself in six directions: upward, downward, forward, backward, to left and to right. They have four different styles of flight.

- Counter-stroking, with forewings beating 180° out of phase with the hindwings, is used for hovering and slow flight. This style is efficient and generates a large amount of lift.

- Phased-stroking, with the hindwings beating 90° ahead of the forewings, is used for fast flight. This style creates more thrust, but less lift than counter-stroking.

- Synchronised-stroking, with forewings and hindwings beating together, is used when changing direction rapidly, as it maximises thrust.

- Gliding, with the wings held out, is used in three situations: free gliding, for a few seconds in between bursts of powered flight; gliding in the updraft at the crest of a hill, effectively hovering by falling at the same speed as the updraft; and in certain dragonflies such as darters, when "in cop" with a male, the female sometimes simply glides while the male pulls the pair along by beating his wings.

The wings are powered directly, unlike most families of insects, with the flight muscles attached to the wing bases. Dragonflies have a high power/weight ratio, and have been documented accelerating at 4 G linearly and 9 G in sharp turns while pursuing prey.

Dragonflies generate lift in at least four ways at different times, including classical lift like an aircraft wing; supercritical lift with the wing above the critical angle, generating high lift and using very short strokes to avoid stalling; and creating and shedding vortices. Some families appear to use special mechanisms, as for example the Libellulidae which take off rapidly, their wings beginning pointed far forward and twisted almost vertically. Dragonfly wings behave highly dynamically during flight, flexing and twisting during each beat. Among the variables are wing curvature, length and speed of stroke, angle of attack, forward/back position of wing, and phase relative to the other wings.

Flight speed

Old and unreliable claims are made that dragonflies such as the southern giant darner can fly up to 97 km/h (60 mph). However, the greatest reliable flight speed records are for other types of insects. In general, large dragonflies like the hawkers have a maximum speed of 36–54 km/h (22–34 mph) with average cruising speed of about 16 km/h (9.9 mph). Dragonflies can travel at 100 body-lengths per second in forward flight, and three lengths per second backwards.

Motion camouflage

In high-speed territorial battles between male Australian emperors (Hemianax papuensis), the fighting dragonflies adjust their flight paths to appear stationary to their rivals, minimizing the chance of being detected as they approach. To achieve the effect, the attacking dragonfly flies towards his rival, choosing his path to remain on a line between the rival and the start of his attack path. The attacker thus looms larger as he closes on the rival, but does not otherwise appear to move. Researchers found that six of 15 encounters involved motion camouflage.

Temperature control

The flight muscles need to be kept at a suitable temperature for the dragonfly to be able to fly. Being cold-blooded, they can raise their temperature by basking in the sun. Early in the morning, they may choose to perch in a vertical position with the wings outstretched, while in the middle of the day, a horizontal stance may be chosen. Another method of warming up used by some larger dragonflies is wing-whirring, a rapid vibration of the wings that causes heat to be generated in the flight muscles. The green darner (Anax junius) is known for its long-distance migrations, and often resorts to wing-whirring before dawn to enable it to make an early start.

Becoming too hot is another hazard, and a sunny or shady position for perching can be selected according to the ambient temperature. Some species have dark patches on the wings which can provide shade for the body, and a few use the obelisk posture to avoid overheating. This behaviour involves doing a "handstand", perching with the body raised and the abdomen pointing towards the sun, thus minimising the amount of solar radiation received. On a hot day, dragonflies sometimes adjust their body temperature by skimming over a water surface and briefly touching it, often three times in quick succession. This may also help to avoid desiccation.

Feeding

Adult dragonflies hunt on the wing using their exceptionally acute eyesight and strong, agile flight. They are almost exclusively carnivorous, eating a wide variety of insects ranging from small midges and mosquitoes to butterflies, moths, damselflies, and smaller dragonflies. A large prey item is subdued by being bitten on the head and is carried by the legs to a perch. Here, the wings are discarded and the prey usually ingested head first. A dragonfly may consume as much as a fifth of its body weight in prey per day. Dragonflies are also some of the insect world's most efficient hunters, catching up to 95% of the prey they pursue.

The nymphs are voracious predators, eating most living things that are smaller than they are. Their staple diet is mostly bloodworms and other insect larvae, but they also feed on tadpoles and small fish. A few species, especially those that live in temporary waters, are likely to leave the water to feed. Nymphs of Cordulegaster bidentata sometimes hunt small arthropods on the ground at night, while some species in the Anax genus have even been observed leaping out of the water to attack and kill full-grown tree frogs.

Eyesight

Dragonfly vision is thought to be like slow motion for humans. Dragonflies see faster than humans do; they see around 200 images per second. A dragonfly can see in 360 degrees, and nearly 80 per cent of the insect's brain is dedicated to its sight.

Predators

Although dragonflies are swift and agile fliers, some predators are fast enough to catch them. These include falcons such as the American kestrel, the merlin, and the hobby; nighthawks, swifts, flycatchers and swallows also take some adults; some species of wasps, too, prey on dragonflies, using them to provision their nests, laying an egg on each captured insect. In the water, various species of ducks and herons eat dragonfly nymphs and they are also preyed on by newts, frogs, fish, and water spiders. Amur falcons, which migrate over the Indian Ocean at a period that coincides with the migration of the globe skimmer dragonfly, Pantala flavescens, may actually be feeding on them while on the wing.

Parasites

Dragonflies are affected by three groups of parasites: water mites, gregarine protozoa, and trematode flatworms (flukes). Water mites, Hydracarina, can kill smaller dragonfly nymphs, and may also be seen on adults. Gregarines infect the gut and may cause blockage and secondary infection. Trematodes are parasites of vertebrates such as frogs, with complex life cycles often involving a period as a stage called a cercaria in a secondary host, a snail. Dragonfly nymphs may swallow cercariae, or these may tunnel through a nymph's body wall; they then enter the gut and form a cyst or metacercaria, which remains in the nymph for the whole of its development. If the nymph is eaten by a frog, the amphibian becomes infected by the adult or fluke stage of the trematode.

Dragonflies and humans

Conservation

Most odonatologists live in temperate areas and the dragonflies of North America and Europe have been the subject of much research. However, the majority of species live in tropical areas and have been little studied. With the destruction of rainforest habitats, many of these species are in danger of becoming extinct before they have even been named. The greatest cause of decline is forest clearance with the consequent drying up of streams and pools which become clogged with silt. The damming of rivers for hydroelectric schemes and the drainage of low-lying land has reduced suitable habitat, as has pollution and the introduction of alien species.

In 1997, the International Union for Conservation of Nature set up a status survey and conservation action plan for dragonflies. This proposes the establishment of protected areas around the world and the management of these areas to provide suitable habitat for dragonflies. Outside these areas, encouragement should be given to modify forestry, agricultural, and industrial practices to enhance conservation. At the same time, more research into dragonflies needs to be done, consideration should be given to pollution control and the public should be educated about the importance of biodiversity.

Habitat degradation has reduced dragonfly populations across the world, for example in Japan. Over 60% of Japan's wetlands were lost in the 20th century, so its dragonflies now depend largely on rice fields, ponds, and creeks. Dragonflies feed on pest insects in rice, acting as a natural pest control. Dragonflies are steadily declining in Africa, and represent a conservation priority.

The dragonfly's long lifespan and low population density makes it vulnerable to disturbance, such as from collisions with vehicles on roads built near wetlands. Species that fly low and slow may be most at risk.

Dragonflies are attracted to shiny surfaces that produce polarization which they can mistake for water, and they have been known to aggregate close to polished gravestones, solar panels, automobiles, and other such structures on which they attempt to lay eggs. These can have a local impact on dragonfly populations; methods of reducing the attractiveness of structures such as solar panels are under experimentation.

In culture

A blue-glazed faience dragonfly amulet was found by Flinders Petrie at Lahun, from the Late Middle Kingdom of ancient Egypt.

For the Navajo, dragonflies symbolize pure water. Often stylized in a double-barred cross design, dragonflies are a common motif in Zuni pottery, as well as Hopi rock art and Pueblo necklaces.

As a seasonal symbol in Japan, dragonflies are associated with the season of autumn. In Japan, they are symbols of rebirth, courage, strength, and happiness. They are also depicted frequently in Japanese art and literature, especially haiku poetry. Japanese children catch large dragonflies as a game, using a hair with a small pebble tied to each end, which they throw into the air. The dragonfly mistakes the pebbles for prey, gets tangled in the hair, and is dragged to the ground by the weight.

In both China and Japan, dragonflies have been used in traditional medicine. In Indonesia, adult dragonflies are caught on poles made sticky with birdlime, then fried in oil as a delicacy.

Images of dragonflies are common in Art Nouveau, especially in jewellery designs. They have also been used as a decorative motif on fabrics and home furnishings. Douglas, a British motorcycle manufacturer based in Bristol, named its innovatively designed postwar 350-cc flat-twin model the Dragonfly.

Among the classical names of Japan are Akitsukuni (秋津国), Akitsushima (秋津島), Toyo-akitsushima (豊秋津島). Akitsu is an old word for dragonfly, so one interpretation of Akitsushima is "Dragonfly Island". This is attributed to a legend in which Japan's mythical founder, Emperor Jimmu, was bitten by a mosquito, which was then eaten by a dragonfly.

In Europe, dragonflies have often been seen as sinister. Some English vernacular names, such as "horse-stinger", "devil's darning needle", and "ear cutter", link them with evil and injury. Some of these reference the popular misconception that dragonflies can bite or sting humans. Swedish folklore holds that the devil uses dragonflies to weigh people's souls. The Norwegian name for dragonflies is Øyenstikker ("eye-poker"), and in Portugal, they are sometimes called tira-olhos ("eyes-snatcher"). They are often associated with snakes, as in the Welsh name gwas-y-neidr, "adder's servant". The Southern United States terms "snake doctor" and "snake feeder" refer to a folk belief that dragonflies catch insects for snakes or follow snakes around and stitch them back together if they are injured.

The watercolourist Moses Harris (1731–1785), known for his The Aurelian or natural history of English insects (1766), published in 1780, the first scientific descriptions of several Odonata including the banded demoiselle, Calopteryx splendens. He was the first English artist to make illustrations of dragonflies accurate enough to be identified to species (Aeshna grandis at top left of plate illustrated), though his rough drawing of a nymph (at lower left) with the mask extended appears to be plagiarised.

More recently, dragonfly watching has become popular in America as some birdwatchers seek new groups to observe.

In heraldry, like other winged insects, the dragonfly is typically depicted tergiant (with its back facing the viewer), with its head to chief (at the top).

-

Faience amulets from Memphite region, ancient Egypt Middle Kingdom, 12-13 Dynasty

-

Accurately drawn dragonflies by Moses Harris, 1780: At top left, the brown hawker, Aeshna grandis (described by Linnaeus, 1758); the nymph at lower left is shown with the "mask" extended.

-

Woodcut on paper, after Kitagawa Utamaro, 1788

-

Tiffany dragonfly pendant lamp, designed c. 1903

In poetry and literature

Lafcadio Hearn wrote in his 1901 book A Japanese Miscellany that Japanese poets had created dragonfly haiku "almost as numerous as are the dragonflies themselves in the early autumn." The poet Matsuo Bashō (1644–1694) wrote haiku such as "Crimson pepper pod / add two pairs of wings, and look / darting dragonfly", relating the autumn season to the dragonfly. Hori Bakusui (1718–1783) similarly wrote "Dyed he is with the / Colour of autumnal days, / O red dragonfly."

The poet Lord Tennyson, described a dragonfly splitting its old skin and emerging shining metallic blue like "sapphire mail" in his 1842 poem "The Two Voices", with the lines "An inner impulse rent the veil / Of his old husk: from head to tail / Came out clear plates of sapphire mail."

The novelist H. E. Bates described the rapid, agile flight of dragonflies in his 1937 nonfiction book Down the River:

I saw, once, an endless procession, just over an area of water-lilies, of small sapphire dragonflies, a continuous play of blue gauze over the snowy flowers above the sun-glassy water. It was all confined, in true dragonfly fashion, to one small space. It was a continuous turning and returning, an endless darting, poising, striking and hovering, so swift that it was often lost in sunlight.

In technology

A dragonfly has been genetically modified with light-sensitive "steering neurons" in its nerve cord to create a cyborg-like "DragonflEye". The neurons contain genes like those in the eye to make them sensitive to light. Miniature sensors, a computer chip, and a solar panel were fitted in a "backpack" over the insect's thorax in front of its wings. Light is sent down flexible light-pipes named optrodes from the backpack into the nerve cord to give steering commands to the insect. The result is a "micro-aerial vehicle that's smaller, lighter and stealthier than anything else that's manmade".

Notes

- ^ This is not to say that other species may not use the same technique, only that this species has been studied.

- ^ Reviewing his artwork, the odonatologists Albert Orr and Matti Hämäläinen comment that his drawing of a 'large brown' (Aeshna grandis, top left of image) was "superb", while the "perfectly natural colours of the eyes indicate that Harris had examined living individuals of these aeshnids and either coloured the printed copper plates himself or supervised the colourists." However, they consider the nymph on the same plate far less good, "a very stiff dorso-lateral view of an aeshnid larva with mask extended. No attempt has been made to depict the eyes, antennae or hinge on the mask or labial palps, all inconceivable omissions for an artist of Harris' talent had he actually examined a specimen", and they suggest he copied it from August Johann Rösel von Rosenhof.

- ^ Optrode is a portmanteau of "optical electrode".

References

- ^ Selys-Longchamps, E. (1854). Monographie des caloptérygines (in French). Vol. t.9e. Brussels and Leipzig: C. Muquardt. pp. 1–291 [1–2]. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.60461.

- ^ Dijkstra, Klaas-Douwe B.; Bechly, Günter; Bybee, Seth M.; Dow, Rory A.; Dumont, Henri J.; Fleck, Günther; Garrison, Rosser W.; Hämäläinen, Matti; Kalkman, Vincent J.; Karube, Haruki; May, Michael L.; Orr, Albert G.; Paulson, Dennis R.; Rehn, Andrew C.; Theischinger, Günther; Trueman, John W.H.; Van Tol, Jan; von Ellenrieder, Natalia; Ware, Jessica (2013). "The classification and diversity of dragonflies and damselflies (Odonata). In: Zhang, Z.-Q. (Ed.) Animal Biodiversity: An Outline of Higher-level Classification and Survey of Taxonomic Richness (Addenda 2013)". Zootaxa. 3703 (1): 36–45. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3703.1.9. hdl:10072/61365. ISSN 1175-5334.

- ^ Paulson, D.; Schorr, M.; Abbott, J.; Bota-Sierra, C.; Deliry, C.; Dijkstra, K.-D.; Lozano, F. (2024). "World Odonata List". OdonataCentral, University of Alabama. Retrieved 4 October 2024.

- ^ Cannings, Robert A.; Stuart, Kathleen M. (1977). The Dragonflies of British Columbia (first ed.). Victoria, British Columbia, Canada: British Columbia Provincial Museum. p. 19.

- ^ Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert (1940). "ἄνισος". A Greek-English Lexicon. Perseus Digital Library.

- ^ Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert (1940). "πτερόν". A Greek-English Lexicon. Perseus Digital Library.

- ^ Gordh, G.; Headrick, D. (2011). A dictionary of entomology (2nd ed.). CABI Books. pp. 74–75. ISBN 978-1-84593-542-9.

- ^ The Biology of Dragonflies. CUP Archive. 2018-10-13. p. 324. GGKEY:0Z7A1R071DD.

No dragonfly at present existing can compare with the immense Meganeura monyi of the Upper Carboniferous, whose expanse of wing was somewhere about 27 inches.

- ^ Resh, Vincent H.; Cardé, Ring T. (22 July 2009). Encyclopedia of Insects. Academic Press. p. 722. ISBN 978-0-08-092090-0.

- ^ Huguet, Aurélien; Nel, André; Martinez-Delclos, Xavier; Bechly, Gunter; Martins-Neto, Rafael (2002). "Preliminary phylogenetic analysis of the Protanisoptera (Insecta: Odonatoptera)". Geobios. 35 (5): 537–560. Bibcode:2002Geobi..35..537H. doi:10.1016/s0016-6995(02)00071-2. ISSN 0016-6995. S2CID 81495925.

- ^ Etter, Walter; Kuhn, Olivier (2000). "An Articulated Dragonfly (Insecta, Odonata) From The Upper Liassic Posidonia Shale Of Northern Switzerland". Palaeontology. 43 (5): 967–977. Bibcode:2000Palgy..43..967E. doi:10.1111/1475-4983.00157. ISSN 0031-0239. S2CID 140165815.

- ^ Kohli, Manpreet Kaur; Ware, Jessica L.; Bechly, Günter (2016). "How to date a dragonfly: Fossil calibrations for odonates". Palaeontologia Electronica. 19 (1): 576. doi:10.26879/576.

- ^ Grimaldi, David; Engel, Michael S. (2005). Evolution of the Insects. Cambridge University Press. pp. 175–187. ISBN 9780521821490.

- ^ Zhang, Z.-Q. (2011). "Phylum Arthropoda (von Siebold, 1848) In: Zhang, Z.-Q. (ed.) Animal Biodiversity: An outline of higher-level classification and survey of taxonomic richness" (PDF). Zootaxa. 3148: 99–103. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3148.1.14.

- ^ Dunkle, Sidney W. (2000). Dragonflies through Binoculars: A field guide to the dragonflies of North America. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-511268-9.

- ^ Bybee, Seth M.; Kalkman, Vincent J.; Erickson, Robert J.; Frandsen, Paul B.; Breinholt, Jesse W.; Suvorov, Anton; et al. (2021). "Phylogeny and classification of Odonata using targeted genomics". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 160: 107115. Bibcode:2021MolPE.16007115B. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2021.107115. hdl:11093/2768. ISSN 1055-7903. PMID 33609713.

- ^ Suhling, F.; Sahlén, G.; Gorb, S.; Kalkman, V.J.; Dijkstra, K-D.B.; van Tol, J. (2015). "Order Odonata". In Thorp, James; Rogers, D. Christopher (eds.). Ecology and general biology. Thorp and Covich's Freshwater Invertebrates (4 ed.). Academic Press. pp. 893–932. ISBN 9780123850263.

- ^ Bybee, Seth (May 2012) [August 2005]. "Featured Creatures: dragonflies and damselflies". University of Florida. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ^ Garrison, Rosser W.; Ellenrieder, Natalia von; Louton, Jerry A. (16 August 2006). Dragonfly Genera of the New World: An Illustrated and Annotated Key to the Anisoptera. JHU Press. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-8018-8446-7.

- ^ "Emperor dragonfly (Anax imperator)". Arkive.org. Archived from the original on 2015-04-09. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ^ Powell 1999, p. 9.

- ^ Polcyn, D. M. (August 1994). "Thermoregulation During Summer Activity in Mojave Desert Dragonflies (Odonata: Anisoptera)". Functional Ecology. 8 (4): 441–449. Bibcode:1994FuEco...8..441P. doi:10.2307/2390067. JSTOR 2390067.

- ^ Carchini, G.; Solimini, Angelo; Ruggiero, A. (2005). "Habitat Characteristics and Odonata Diversity in Mountain Ponds of Central Italy". Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems. 15 (6): 573–581. Bibcode:2005ACMFE..15..573C. doi:10.1002/aqc.741.

- ^ Mani, M.S. (1968). Ecology and Biogeography of High Altitude Insects. Springer. p. 246. ISBN 978-90-6193-114-0.

- ^ "Dragonfly Spotted In Iceland". Reykjavik Grapevine. 26 August 2011. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- ^ Smetanin, A. N. (2013). "On the Insect Fauna of the Kichiga River Basin, Northeastern Kamchatka". Entomological Review. 93 (2): 160–173. Bibcode:2013EntRv..93..160S. doi:10.1134/s0013873813020048. S2CID 32417175.

- ^ Hudson, John; Armstrong, Robert H. (2010). Dragonflies of Alaska (PDF) (Second ed.). Nature Alaska Images. pp. 5, 32. ISBN 978-1-57833-302-8.

- ^ Ruppert, Edward E.; Fox, Richard, S.; Barnes, Robert D. (2004). Invertebrate Zoology, 7th edition. Cengage Learning. p. 745. ISBN 978-81-315-0104-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pritchard, Gordon (1966). "On the morphology of the compound eyes of dragonflies (Odonata: Anisoptera), with special reference to their role in prey capture". Proceedings of the Royal Entomological Society of London. 41 (1–3): 1–8. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3032.1966.tb01126.x.

- ^ "Introduction to the Odonata". UCMP Berkeley. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- ^ Berger 2004, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Needham, J.G. (1975). A Manual of the Dragonflies of North America. University of California Press. pp. 10–21. GGKEY:5YCUC2C45TH.

- ^ Paulson, Dennis (2011). Dragonflies and Damselflies of the East. Princeton University Press. pp. 29–32. ISBN 978-1-4008-3966-7.

- ^ Miller, P. L. (1991). "The structure and function of the genitalia in the Libellulidae (Odonata)". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 102 (1): 43–73. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1991.tb01536.x.

- ^ Miller, P. L. (1995). "Sperm competition and penis structure in some Libellulid dragonflies (Anisoptera)". Odonatologica. 24 (1): 63–72. Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- ^ Battin, Tom J. (1993). "The odonate mating system, communication, and sexual selection: A review". Italian Journal of Zoology. 60 (4): 353–360. doi:10.1080/11250009309355839.

- ^ Tennessen, K.J. (2009). "Odonata (Dragonflies, Damselflies)". In Resh, Vincent H.; Carde, Ring T. (eds.). Encyclopedia of Insects (2 ed.). Academic Press. pp. 721–729.

- ^ Lawlor, Elizabeth P. (1999). Discover Nature in Water & Wetlands: Things to Know and Things to Do. Stackpole Books. pp. 88, 94–96. ISBN 978-0-8117-2731-0.

- ^ Aquatic Entomology

- ^ Insect Physiology

- ^ Powell 1999, p. 102.

- ^ Prum, Richard O.; Cole, Jeff A.; Torres, Rodolfo H. (15 October 2004). "Blue integumentary structural colours in dragonflies (Odonata) are not produced by incoherent Tyndall scattering" (PDF). Journal of Experimental Biology. 207 (22): 3999–4009. Bibcode:2004JExpB.207.3999P. doi:10.1242/jeb.01240. hdl:1808/1601. PMID 15472030. S2CID 15900357.

- ^ Dijkstra 2006, pp. 26–35.

- ^ Dijkstra 2006, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Levine, Todd D.; Lang, Brian K.; Berg, David J. (2009). "Parasitism of Mussel Gills by Dragonfly Nymphs". The American Midland Naturalist. 162 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1674/0003-0031-162.1.1.

- ^ Dijkstra 2006, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Dijkstra 2006, pp. 243, 272.

- ^ Dijkstra 2006, p. 246.

- ^ Ratcliffe, Derek (26 January 2012). A Nature Conservation Review: Volume 1: The Selection of Biological Sites of National Importance to Nature Conservation in Britain. Cambridge University Press. pp. 378–379. ISBN 978-0-521-20329-6.

- ^ Berger 2004, pp. 32–34.

- ^ Lojewski, Jeffrey A.; Switzer, Paul V. (1 March 2015). "The role of landmarks in territory maintenance by the black saddlebags dragonfly, Tramea lacerata". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 69 (3): 347–355. Bibcode:2015BEcoS..69..347L. doi:10.1007/s00265-014-1847-z. ISSN 1432-0762. S2CID 17617885.

- ^ Fincke, Ola M. (2004). "Polymorphic signals of harassed female odonates and the males that learn them support a novel frequency-dependent model". Animal Behaviour. 67 (5): 833–845. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2003.04.017. S2CID 15705194.

- ^ Khelifa, Rassim (2017). "Faking death to avoid male coercion: Extreme sexual conflict resolution in a dragonfly". Ecology. 98 (6): 1724–1726. Bibcode:2017Ecol...98.1724K. doi:10.1002/ecy.1781. PMID 28436995. S2CID 42601970.

- ^ Dolný, Aleš; Harabiš, Filip; Mižičová, Hana (2014-07-09). "Home Range, Movement, and Distribution Patterns of the Threatened Dragonfly Sympetrum depressiusculum (Odonata: Libellulidae): A Thousand Times Greater Territory to Protect?". PLOS ONE. 9 (7): e100408. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9j0408D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0100408. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4090123. PMID 25006671.

- ^ Cordero-Rivera, Adolfo; Cordoba-Aguilar, Alex (2010). 15. Selective Forces Propelling Genitalic Evolution in Odonata (PDF). p. 343.

- ^ Trueman & Rowe 2009, p. Life Cycle and Behavior.

- ^ Berger 2004, p. 39: "Romantic souls are pleased to note that at the climactic moment, the two slender bodies form a delicate heart shape. Experts say the pair is now 'in cop'."

- ^ Reinhardt, Klaus (2005). "Sperm numbers, sperm storage duration and fertility limitation in the Odonata". International Journal of Odonatology. 8 (1): 45–58. Bibcode:2005IJOdo...8...45R. doi:10.1080/13887890.2005.9748242. ISSN 1388-7890.

- ^ Cardé, Ring T.; Resh, Vincent H. (2012). A World of Insects: The Harvard University Press Reader. Harvard University Press. pp. 195–197. ISBN 978-0-674-04619-1.

- ^ Berger 2004, p. 39.

- ^ Bybee, Seth (1 May 2012). "Dragonflies and damselflies: Odonata". Featured Creatures. University of Florida: Entomology and Nematology. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- ^ Mill, P. J.; Pickard, R. S. (1975). "Jet-propulsion in anisopteran dragonfly nymphs". Journal of Comparative Physiology A. 97 (4): 329–338. doi:10.1007/BF00631969. S2CID 45066664.

- ^ Corbet, Philip S. (1980). "Biology of odonata". Annual Review of Entomology. 25: 189–217. doi:10.1146/annurev.en.25.010180.001201.

- ^ Berger 2004, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Berger 2004, p. 9.

- ^ Foster, S.E; Soluk, D.A (2006). "Protecting more than the wetland: The importance of biased sex ratios and habitat segregation for conservation of the Hine's emerald dragonfly, Somatochlora hineana Williamson". Biological Conservation. 127 (2): 158–166. Bibcode:2006BCons.127..158F. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2005.08.006.

- ^ Waldbauer, Gilbert (2006). A Walk Around the Pond: Insects in and Over the Water. Harvard University Press. p. 105. ISBN 9780674022119.

- ^ Rowe, Richard J. "Dragonfly Flight". Tree of Life. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ^ Tillyard, Robert John (1917). The Biology of Dragonflies (PDF). pp. 322–323. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 July 2017. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

I doubt if any greater speed than this occurs amongst Odonata

- ^ Dean, T. J. (2003-05-01). "Chapter 1 — Fastest Flyer". Book of Insect Records. University of Florida. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions about Dragonflies". British Dragonfly Society. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- ^ Hopkin, Michael (June 5, 2003). "Nature News". Dragonfly Flight Tricks the Eye. Nature.com. doi:10.1038/news030602-10. Retrieved January 16, 2012.

- ^ Mizutani, A. K.; Chahl, J. S.; Srinivasan, M. V. (June 5, 2003). "Insect behaviour: Motion camouflage in dragonflies". Nature. 65 (423): 604. Bibcode:2003Natur.423..604M. doi:10.1038/423604a. PMID 12789327. S2CID 52871328.

- ^ Glendinning, Paul (27 January 2004). "The mathematics of motion camouflage". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences. 271 (1538): 477–81. doi:10.1098/rspb.2003.2622. PMC 1691618. PMID 15129957.

- ^ Berger 2004, pp. 44–46.

- ^ Berger 2004, p. 31.

- ^ Powell 1999, p. 12.

- ^ Combes, S.A.; Rundle, D.E.; Iwasaki, J.M.; Crall, J.D. (2012). "Linking biomechanics and ecology through predator–prey interactions: flight performance of dragonflies and their prey". Journal of Experimental Biology. 215 (6): 903–913. Bibcode:2012JExpB.215..903C. doi:10.1242/jeb.059394. PMID 22357584.

- ^ Linares, Antonio Meira; Maciel-Junior, Jose Amantino Horta; de Mello, Humberto Espirito Santo; Leite, Felipe Sa Fortes (30 April 2016). "First report on predation of adult anurans by Odonata larvae". Salamandra. 52 (1): 42–44. Archived from the original on 24 December 2019. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- ^ "Dragonflies see the world in slow motion". BBC Reel. Retrieved 2023-08-11.

- ^ "The Symbolism, Biology and Lore of Dragonflies | The Dragonfly Foundation". Retrieved 2023-08-11.

- ^ Berger 2004, pp. 48–49.

- ^ "Hobby". BBC Nature. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ^ Meister 2001, p. 16.

- ^ Anderson, R. Charles (2009). "Do dragonflies migrate across the western Indian Ocean?". Journal of Tropical Ecology. 25 (4): 347–358. doi:10.1017/S0266467409006087. S2CID 86187189.

- ^ Mead, Kurt. "Dragonfly Biology 101". Minnesota Dragonfly Society. Archived from the original on 27 February 2015. Retrieved 27 February 2015.

- ^ Córdoba-Aguilar, Alex (28 August 2008). Dragonflies and Damselflies: Model Organisms for Ecological and Evolutionary Research. OUP Oxford. p. 176. ISBN 978-0-19-155223-6.

- ^ "An Introduction To The Study of Invertebrate Zoology. Platyhelminthes". University of California, Riverside. Retrieved 27 February 2015.

- ^ Moore, N.W. (1997). "Dragonflies: status survey and conservation action plan" (PDF). International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 13 September 2017.

- ^ Taku, Kadoya; Shin-ichi, Suda; Izumi, Washitani (2009). "Dragonfly Crisis in Japan: A likely Consequence of Recent Agricultural Habitat Degradation". Biological Conservation. 142 (9): 1889–1905. Bibcode:2009BCons.142.1899K. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2009.02.033.

- ^ Channa N. B. Bambaradeniya; Felix P. Amerasinghe (2004). Biodiversity associated with the rice field agroecosystem in Asian countries: A brief review. IWMI. p. 10. ISBN 978-92-9090-532-5.

- ^ Washitani, Izumi (2008). "Restoration of Biologically-Diverse Floodplain Wetlands Including Paddy Fields". Global Environmental Research. 12: 95–99.

- ^ Simaika, John P.; Samways, Michael J.; Kipping, Jens; Suhling, Frank; Dijkstra, Klaas-Douwe B.; Clausnitzer, Viola; Boudot, Jean Pierre; Domisch, Sami (2013). "Continental-Scale Conservation Prioritization of African Dragonflies". Biological Conservation. 157: 245–254. Bibcode:2013BCons.157..245S. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2012.08.039.

- ^ Soluk, Daniel A.; Zercher, Deanna S.; Worthington, Amy M. (2011). "Influence of roadways on patterns of mortality and flight behavior of adult dragonflies near wetland areas". Biological Conservation. 144 (5): 1638–1643. Bibcode:2011BCons.144.1638S. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2011.02.015.

- ^ Horvath, Gabor; Blaho, Miklos; Egri, Adam; Kriska, Gyorgy; Seres, Istvan; Robertson, Bruce (2010). "Reducing the Maladaptive Attractiveness of Solar Panels to Polarotactic Insects". Conservation Biology. 24 (6): 1644–1653. Bibcode:2010ConBi..24.1644H. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2010.01518.x. PMID 20455911. S2CID 39299883.

- ^ Horvath, Gabor; Malik, Peter; Kriska, Gyorgy; Wildermuth, Hansruedi (2007). "Ecological traps for dragonflies in a cemetery: the attraction of Sympetrum species (Odonata: Libellulidae)by horizontally polarizing black gravestones". Freshwater Biology. 52 (9): 1700–1709. Bibcode:2007FrBio..52.1700H. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2427.2007.01798.x.

- ^ "Beads UC7549". Petrie Museum Catalogue. The Petrie Museum, UCL. Archived from the original on 16 September 2017. Retrieved 10 June 2015. There is a photograph in the catalogue; it is free for non-commercial usage.

- ^ Mitchell, Forrest L.; Lasswell, James L. (2005). A Dazzle of Dragonflies. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-1-58544-459-5.

- ^ Baird, Merrily (2001). Symbols of Japan: Thematic Motifs in Art and Design. New York: Rizzoli. pp. 108–109. ISBN 978-0-8478-2361-1.

- ^ Corbet 1999, p. 559.

- ^ Moonan, Wendy (August 13, 1999). "Dragonflies Shimmering as Jewelry". The New York Times. pp. E2:38.

- ^ Large, Elizabeth (June 27, 1999). "The latest buzz; In the world of design, dragonflies are flying high". The Sun (Baltimore, MD). p. 6N. Archived from the original on 2015-02-23. Retrieved 2014-09-02.

- ^ Brown, Roland (November–December 2007). "1955 Douglas Dragonfly". Motorcycle Classics. Retrieved 2009-08-10.

- ^ Nussbaum, Louis Frédéric; Käthe Roth (2005). "Akitsushima". Japan Encyclopedia. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. p. 20. ISBN 9780674017535.

- ^ Nihonto

- ^ 杉浦洋一 (Youichi Sugiura); John K. Gillespie (ジョン・K・ギレスピー) (1999). 日本文化を英語で紹介する事典 [A Bilingual Handbook on Japanese Culture] (in Japanese and English). Chiyoda, Tokyo: Natsume Group. p. 305. ISBN 978-4-8163-2646-2. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

- ^ Trueman, John W. H.; Rowe, Richard J. "Odonata: Dragonflies and Damselflies". Tree of Life. Retrieved 27 February 2015.

- ^ Corbet 1999, pp. 559–561.

- ^ Jones, Richard (5 November 2015). "Do dragonflies bite or sting humans?". BBC Wildlife. Retrieved July 6, 2024.

- ^ Hand, Wayland D. (1973). "From Idea to Word: Folk Beliefs and Customs Underlying Folk Speech". American Speech. 48 (1/2): 67–76. doi:10.2307/3087894. JSTOR 3087894.

- ^ Newton, Blake (16 August 2008) [2004]. "Dragonflies". University of Kentucky Entomology.

- ^ Orr, Albert G.; Hämäläinen, Matti (July 2014). "Plagiarism or pragmatism – who cares? An analysis of some 18th century dragonfly illustrations". Agrion. 18 (2): 26–30.

- ^ Adams, Jill U. (July 2012). "Chasing Dragonflies and Damselflies". Audubon (July–August 2012). Retrieved 6 August 2018.

- ^ "Insects".

- ^ Waldbauer, Gilbert (30 June 2009). A Walk around the Pond: insects in and over the water. Harvard University Press. p. 247. ISBN 978-0-674-04477-7.

- ^ Mitchell, Forrest Lee; Lasswell, James (2005). A Dazzle Of Dragonflies. Texas A&M University Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-58544-459-5.

- ^ Tennyson, Alfred, Lord (17 November 2013). Delphi Complete Works of Alfred, Lord Tennyson (Illustrated). Delphi Classics. pp. 544–545. ISBN 978-1-909496-24-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Down the River". H. E. Bates official author website. Archived from the original on 2021-09-09. Retrieved 9 September 2021.

- ^ Powell 1999, p. 7.

- ^ Bates, H. E. (12 February 1937). "Country Life: Pike and Dragonflies". The Spectator. No. 5668. p. 269 (online p. 17).

- ^ "Equipping Insects for Special Service". Draper. 19 January 2017.

- ^ Ackerman, Evan (1 June 2017). "Draper's Genetically Modified Cyborg DragonflEye Takes Flight". IEEE Spectrum.

Sources

- Berger, Cynthia (2004). Dragonflies. Stackpole Books. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-8117-2971-0.

- Corbet, Phillip S. (1999). Dragonflies: Behavior and Ecology of Odonata. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. pp. 559–561. ISBN 978-0-8014-2592-9.

- Dijkstra, Klaas-Douwe B. (2006). Field Guide to the Dragonflies of Britain and Europe. British Wildlife Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9531399-4-1.

- Meister, Cari (2001). Dragonflies. ABDO. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-57765-461-2.

- Powell, Dan (1999). A Guide to the Dragonflies of Great Britain. Arlequin Press. ISBN 978-1-900-15901-2.

- Trueman, John W. H.; Rowe, Richard J. (2009). "Odonata". Tree of Life. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

External links

The dictionary definition of dragonfly at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of dragonfly at Wiktionary Media related to Anisoptera at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Anisoptera at Wikimedia Commons Data related to Anisoptera at Wikispecies

Data related to Anisoptera at Wikispecies