Atlantic U-boat Campaign (World War I)

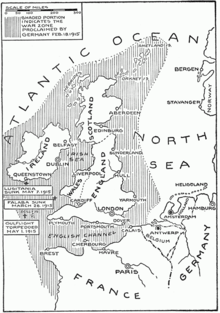

Initially the U-boat campaign was directed against the warships of the British Grand Fleet. Later U-boat fleet action was extended to include action against the trade routes of the Allied powers. This campaign was highly destructive, and resulted in the loss of nearly half of Britain's initial merchant marine fleet during the course of the war. To counter the German submarines, the Allies moved shipping into convoys guarded by destroyers, blockades such as the Dover Barrage and minefields such as the North Sea Mine Barrage were laid, and aircraft patrols monitored the U-boat bases. Increased ship construction meant the amount of Allied shipping available remained fairly stable.

The U-boat campaign was thus not able to cut off supplies before the US entered the war in 1917 and in later 1918, the U-boat bases were abandoned in the face of the Allied advance.

The tactical successes and failures of the Atlantic U-boat Campaign would later be used as a set of available tactics in World War II in a similar U-boat war against the British Empire.

1914: Initial campaign

This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2011) |

First patrols

On 6 August 1914, two days after Britain had declared war on Germany, the German U-boats U-5, U-7, U-8, U-9, U-13, U-14, U-15, U-16, U-17, and U-18 sailed from their base in Heligoland to attack Royal Navy warships in the North Sea in the first submarine war patrols in history.

The U-boats sailed north, hoping to encounter Royal Navy squadrons between Shetland and Bergen. On 8 August, one of U-9's engines broke down and she was forced to return to base. On the same day, off Fair Isle, U-15 sighted the British battleships HMS Ajax, Monarch, and Orion on manoeuvres and fired a torpedo at Monarch. This failed to hit, and succeeded only in putting the battleships on their guard. At dawn the next morning, the 1st Light Cruiser Squadron, which was screening the battleships, came into contact with the U-boats. HMS Birmingham sighting U-15, which was lying on the surface. There was no sign of any lookouts on the U-boat and sounds of hammering could be heard, as though her crew were performing repairs. Birmingham immediately altered course and rammed U-15 just behind her conning tower. The submarine was cut in two and sank with all hands.

On 12 August, seven U-boats returned to Heligoland; U-13 was also missing, and it was thought she had been mined. While the operation was a failure, it caused the Royal Navy some uneasiness, disproving earlier estimates as to U-boats' radius of action and leaving the security of the Grand Fleet's unprotected anchorage at Scapa Flow open to question. On the other hand, the ease with which U-15 had been destroyed by Birmingham encouraged the false belief that submarines were no great danger to surface warships.

First action

On 5 September 1914, U-21 commanded by Lieutenant Otto Hersing made history when he torpedoed the Royal Navy light cruiser HMS Pathfinder. The cruiser's magazine exploded, and the ship sank in four minutes, taking 259 of her crew with her. It was the first combat victory of the modern submarine.

The German U-boats were to get even luckier on 22 September. Early in the morning of that day, a lookout on the bridge of U-9, commanded by Lieutenant Otto Weddigen, spotted a vessel on the horizon. Weddigen ordered the U-boat to submerge immediately, and the submarine went forward to investigate. At closer range, Weddigen discovered three old Royal Navy armoured cruisers, HMS Aboukir, Cressy, and Hogue. These three vessels were not merely antiquated, but were staffed mostly by reservists, and were so clearly vulnerable that a decision to withdraw them was already filtering up through the bureaucracy of the Admiralty. The order did not come soon enough for the ships. Weddigen sent one torpedo into Aboukir. The captains of Hogue and Cressy assumed Aboukir had struck a mine and came up to assist. U-9 put two torpedoes into Hogue, and then hit Cressy with two more torpedoes as the cruiser tried to flee. The three cruisers sank in less than an hour, killing 1,460 British sailors.

Three weeks later, on 15 October, Weddigen also sank the old cruiser HMS Hawke, and the crew of U-9 became national heroes. Each was awarded the Iron Cross Second Class, except for Weddigen, who received the Iron Cross First Class. The sinkings caused alarm within the British Admiralty, which was increasingly nervous about the security of the Scapa Flow anchorage, and the fleet was sent to ports in Ireland and the west coast of Scotland until adequate defenses were installed at Scapa Flow. This, in a sense, was a more significant victory than sinking a few old cruisers; the world's most powerful fleet had been forced to abandon its home base. On 18 October, SM U-27 sank HMS E3, the first instance of one submarine sinking another.

End of the first campaign

These concerns were well-founded. On 23 November U-18 penetrated Scapa Flow via Hoxa Sound, following a steamer through the boom and entering the anchorage with little difficulty. However, the fleet was absent, being dispersed in anchorages on the west coast of Scotland and Ireland. As U-18 was making her way back out to the open sea, her periscope was spotted by a guard boat. The trawler Dorothy Gray altered course and rammed the periscope, rendering it unserviceable. U-18 then suffered a failure of her diving plane motor and the boat became unable to maintain her depth, at one point even impacting the seabed. Eventually, her captain was forced to surface and scuttle his command, and all but one crew-member were picked up by British boats.

The last success of the year came on 31 December. U-24 sighted the British battleship HMS Formidable on manoeuvres in the English Channel and torpedoed her. Formidable sank with the loss of 547 of her crew. The C-in-C Channel Fleet, Adm. Sir Lewis Bayly, was criticized for not taking proper precautions during the exercises, but was cleared of the charge of negligence. Bayly later served with distinction as commander of the anti-submarine warfare forces at Queenstown.

1915: War on commerce

First attacks on merchant ships

The first attacks on merchant ships had started in October 1914. On 20 October Glitra became the first British merchant vessel to be sunk by a German submarine in World War I. Glitra, bound from Grangemouth to Stavanger, Norway, was stopped and searched by U-17, under the command of Kapitänleutnant Johannes Feldkirchener. The operation was performed broadly in accordance with the cruiser rules, the crew being ordered into the lifeboats before Glitra was sunk by having her seacocks opened. It was the first time in history a submarine sank a merchant ship.

Less than a week later, on 26 October, U-24 became the first submarine to attack an unarmed merchant ship without warning, when she torpedoed the steamship Admiral Ganteaume, with 2,500 Belgian refugees aboard. Although the ship did not sink, and was towed into Boulogne, 40 people died, mainly due to panic. The U-boat's commander, Rudolf Schneider, claimed he had mistaken her for a troop transport.

On 30 January 1915, U-20, commanded by Kapitänleutnant Otto Dröscher, torpedoed and sank the steamships Ikaria, Tokomaru and Oriole without warning, and on 1 February fired a torpedo at, but missed, the hospital ship Asturias, despite her being clearly identifiable as a hospital ship by her white paintwork with green bands and red crosses.

Unrestricted submarine warfare

Britons believed before the war that the United Kingdom would starve without North American food; W. T. Stead wrote in 1901 that without it "We should be face to face with famine". Arthur Conan Doyle wrote a short story, Danger! suggesting the defeat of the UK using only a small number of submarines. Inspired in part by such tales, German Admirals like von Tirpitz and Hugo von Pohl agitated for a campaign against British commerce with no restrictions, despite the tiny number of submarines available (21 at the start of 1915, 7 of which were undergoing repair work). On 4 February 1915, the first unrestricted campaign against Allied trade was formally started.

In the first month 29 ships totalling 89,517 GRT were sunk, a pace of destruction which was maintained throughout the summer. As the sinkings increased, so too did the number of politically damaging incidents. On 19 February, U-8 torpedoed Belridge, a neutral tanker travelling between two neutral ports; in March U-boats sank Hanna and Medea, a Swedish and a Dutch freighter; in April two Greek vessels.

In March also, Falaba was sunk, with the loss of one US life, and in April Harpalyce, a Belgian Relief ship, was sunk. On 7 May, U-20 sank RMS Lusitania with the loss of 1,197 lives, 124 of them US citizens. These incidents caused outrage amongst neutrals and the scope of the unrestricted campaign was scaled back in September 1915 to lessen the risk of those nations entering the war against Germany.

British countermeasures were largely ineffective. The most effective defensive measures proved to be advising merchantmen to turn towards the U-boat and attempt to ram, forcing it to submerge. Over half of all attacks on merchant ships by U-boats were defeated in this way. This response freed the U-boat to attack without warning, however. On 20 March 1915, this tactic was used by the Great Eastern Railway packet Brussels to escape an attack by U-33. For this her captain, Charles Fryatt, was executed after being captured by the Germans in June 1916, provoking international condemnation.

Another option was arming ships for self-defence, which, according to the Germans, put them outside the protection of the cruiser rules.

Another option was to arm and man decoy ships with hidden guns, the Q-ship. A variant on the idea was to equip small vessels with a submarine escort. In 1915, three U-boats were sunk by Q-ships and two more by submarines accompanying trawlers. In June, U-40 was sunk by HMS C24 while attacking Taranaki, and in July U-23 was sunk by C-27 attacking Princess Louise. Also in July U-36 was sunk by the Q-ship Prince Charles, and in August and September U-27 and U-41 were sunk by Baralong, the former in the notorious Baralong Incident.

There were no means to detect submerged U-boats, and attacks on them were limited to efforts to damage their periscopes with hammers and dropping guncotton bombs. Use of nets to ensnare U-boats was also examined, as was a destroyer, Starfish, fitted with a spar torpedo. U-boats did not cause substantial damage, as merchant traffic was not intimidated into ceasing as the planners had anticipated. Sixteen U-boats were destroyed during this phase of the campaign, while they sank 370 ships of 750,000 GRT. Britain had around 20 million GRT in shipping at the start of the war and production managed to more than keep pace with losses.

1916: In support of the High Seas fleet

1916 was a year of political struggles between opponents and proponents of unrestricted submarine warfare. Reinhard Scheer became the commander of the High Seas Fleet, and as an effort to "blackmail" command into adopting unrestricted submarine warfare, refused to use his submarines in any sort of limited commerce raiding campaign. Thus German Navy returned to a strategy of using the U-boats to erode the Grand Fleet's numerical superiority by staging a series of operations designed to lure the Grand Fleet into a U-boat trap. Due to the U-boats' poor speed compared to the main battle fleet these operations required U-boat patrol lines to be set up, while the High Seas fleet manoeuvred to draw the Grand Fleet to them.

Several of these operations were staged, in March and April 1916, but with no success. Ironically, the major fleet action which did take place, the Battle of Jutland, in May 1916, saw no U-boat involvement at all; the fleets met and engaged largely by chance, and there were no U-boat patrols anywhere near the battle area. A further series of operations, in August and October 1916, were similarly unfruitful, and the strategy was abandoned in favour of resuming commerce warfare. Renewed orders in October suggested that unrestricted submarine warfare may come at some point in the future, but commerce attacks had to operate under cruiser rules for now. To the consternation of Scheer, operating in this way turned out to be a great success, with around 1.4 million tons sunk in less than four months. Only 4 submarines from the High Seas Fleet were lost, due solely to mines or accidents. According to German estimates, Scheer's intransigence cost Germany the opportunity to sink 1.6 to 3 million tons of Allied shipping.

1917: Renewed "unrestricted" campaign

In 1917 Germany decided to resume full unrestricted submarine warfare. It was expected to bring America into the war, but the Germans gambled that they could defeat Britain by this means before the US could mobilize. German planners estimated that if the sunk tonnage were to exceed 600,000 tons per month, Britain would be forced to sue for peace after five to six months.

In February 1917 U-boats sank over 414,000 GRT in the war zone around Britain, 80% of the total for the month; in March they sank over 500,000 (90%), in April over 600,000 of 860,000 GRT, the highest total sinkings of the war. This, however was the high point.

In May, the first convoys were introduced, and were immediately successful. Overall losses started to fall; losses to ships in convoy fell dramatically. In the three months following their introduction, on the Atlantic, North Sea, and Scandinavian routes, of 8,894 ships convoyed just 27 were lost to U-boats. By comparison 356 were lost sailing independently.

As shipping losses fell, U-boat losses rose; during the period May to July 1917, 15 U-boats were destroyed in the waters around Britain, compared to 9 the previous quarter, and 4 for the quarter before the campaign was renewed.

As the campaign became more intense, it also became more brutal. 1917 and 1918 saw a series of attacks on hospital ships, which generally sailed fully lit, to show their non-combatant status. UB-32 damaged HMHS Gloucester Castle in March 1917, U-55 sank HMHS Rewa in January 1918 and U-86 sank HMHS Llandovery Castle in June 1918. Commanded by Wilhelm Werner, U-55 also deliberately drowned dozens of crewmen who had survived the sinkings of the cargo ships Torrington in April 1917 and Belgian Prince in June 1917. As U-boats became more wary, encounters with Q-ships also became more intense. In February 1917 U-83 was sunk by HMS Farnborough, but only after Gordon Campbell, Farnborough's captain, allowed her to be torpedoed in order to get close enough to engage. In March Privet sank U-85 in a 40-minute gun battle, but sank before reaching harbour.

In April Heather was attacked by U-52 and was badly damaged; the U-boat escaped unscathed. And a few days later Tulip was sunk by U-62 whose captain was suspicious of her appearance.

1918: Final year

The convoy system was effective in reducing allied shipping losses, while better weapons and tactics made the escorts more successful at intercepting and attacking U-boats. Shipping losses in Atlantic waters were 98 ships (just over 170,000 GRT) in January; after a rise in February they fell again, and did not rise above that level for the rest of the war. At the same time, ship production increased, especially with the participation of the United States.

In January, six U-boats were destroyed in the theatre; this also became the average loss for the year.

The Allies continued to try to block access through the Straits of Dover, with the Dover Barrage. Until November 1917 it was ineffective; up to then just two U-boats had been destroyed by the Barrage force, and the Barrage itself had been a magnet for surface raids. After major improvement in the winter of 1917 it became more effective; in the four-month period after mid-December seven U-boats were destroyed trying to transit the area, and by February the High Seas Flotilla boats had abandoned the route in favour of sailing north-about round Scotland, with a consequent loss of effectiveness. The Flanders boats still tried to use the route, but continued to suffer losses, and after March switched their operations to Britain's east coast. Other measures, particularly against the Flanders flotilla, were the raids on Zeebrugge and Ostend, an attempt to blockade access to the sea. These were largely unsuccessful; the Flanders boats were able to maintain access throughout this period.

May 1918 saw the only attempt by the Germans to muster a group attack, the forerunner of the wolf-pack, to counter the Allied convoys. In May, six U-boats sailed, under the command of K/L Claus Rücker in U-103. On 11 May, U-86 sank one of a pair of ships detached from a convoy in the Channel, but the next day an attack on the troopship RMS Olympic led to the destruction of U-103, while UB-72 was sunk by British submarine HMS D4. Two more ships were sunk in convoys in the next week, and three independents, but over 100 ships had passed safely through the group's patrol area. During the summer, the extension of the convoy system and effectiveness of the escorts made the east coast of Britain as dangerous for the U-boats as the Channel had become. In this period, the Flanders flotilla lost a third of its boats, and in the autumn, losses were at 40%. In October, with the German army in full retreat, the Flanders flotilla was forced to abandon its base at Bruges before it was overrun. A number of boats were scuttled there, while the remainder, just ten boats, returned to bases in Germany.

In the summer, too, steps were taken to reduce the effectiveness of the High Seas Flotillas. In 1918, the Allies, particularly the US, undertook to create a barrage across the Norwegian Sea, to block U-boat access to the Western Approaches by the north-about route. This huge undertaking involved laying and maintaining minefields and patrols in deep waters over a distance of 300 nautical miles (556 kilometers). The North Sea Mine Barrage saw the laying of over 70,000 mines, mostly by the United States Navy, during the summer of 1918. From September to November 1918, six U-boats were sunk by this measure.

In July 1918, U-156 sailed to Massachusetts and took part in the Attack on Orleans for about an hour. This was the first time that US soil was attacked by a foreign power's artillery since the Siege of Fort Texas in 1846 and one of two places in North America to be subject to attack by the Central Powers. The other was the Battle of Ambos Nogales that was allegedly led by two German spies. On 20 October 1918 Germany suspended submarine warfare, and on 11 November 1918, World War I ended. The last task of the U-boat Arm was in helping to quell the Wilhelmshaven mutiny, which had broken out when the High Seas Fleet was ordered to sea for a final, doomed sortie. After the Armistice, the remaining U-boats joined the High Seas Fleet in surrender, and were interned at Harwich. Of the 12.5 million tons of Allied shipping destroyed in World War I, over 8 million tons, two-thirds of the total, had been sunk in the waters of the Atlantic war zone. Of the 178 U-boats destroyed during the war, 153 had been from the Atlantic forces, 77 from the much larger High Seas Flotillas and 76 from the much smaller Flanders force. Throughout the entire war, the tonnage of available Allied and neutral shipping fluctuated by a maximum of around 5%, and ended the war about 3% higher than at the start.

See also

Notes

- ^ Klovland 2017.

- ^ Gibson and Prendergast 2002, p. 2.

- ^ Messimer 2002, p. 34.

- ^ Halsey 1919, p. 223.

- ^ Halsey, pp. 212–217.

- ^ Halsey, pp. 217–218.

- ^ Messimer, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Halsey, pp. 221–222.

- ^ Messimer 2001, p. 15.

- ^ Prendergast & Gibson 2002, p. 21.

- ^ Stead 1901, pp. 348–349.

- ^ Manson 1977, pp. 70–71.

- ^ Halsey, p. 236.

- ^ The official figures give 1195 lost out of 1959, excluding three stowaways who also were lost. The figures here eliminate some repetitions from the list and people subsequently known not to be on board. "Passenger and Crew Statistics". The Lusitania Resource. Retrieved 27 April 2024.

- ^ Halsey, pp. 248–282.

- ^ Messimer 2001, p. 31.

- ^ Holwitt 2009, p. 93.

- ^ Halsey, pp. 310–312.

- ^ Holwitt, p. 6.; Dönitz, Karl. Memoirs: Ten Years and Twenty Days; von der Poorten, Edward P. The German Navy in World War II (T. Y. Crowell, 1969); Milner, Marc. North Atlantic run: the Royal Canadian Navy and the battle for the convoys (Vanwell Publishing, 2006).

- ^ Tarrant 1989, p. 24.

- ^ McKee 1993, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Klovland 2017, p. 8.

- ^ Manson 1977, p. 355.

- ^ Halpern 1995, p. 329.

- ^ Manson 1977, p. 374

- ^ "U-boat Losses 1914-1918".

- ^ Lundeberg 1963, pp. 111–112.

- ^ Halsey, pp. 335–343, 364–366.

- ^ Tarrant 1989, p. 148.

- ^ Tarrant 1989, p. 43, 49 and 54.

- ^ Grey 1972, p. 243.

- ^ "Murdered by the German who became one of Hitler's henchmen". Southern Daily Echo. Southampton: Newsquest. 1 August 2017. Retrieved 9 May 2023.

- ^ Grey 1972, pp. 177–179.

- ^ Grey 1972, p. 194.

- ^ Klovland, p. 8.

- ^ Tarrant 1989, p. 75.

- ^ Tarrant 1989, pp. 61–62.

- ^ Halpern 1995, p. 407.

- ^ Halsey, pp. 371–378.

- ^ Halpern 1995, p. 427.

- ^ Halpern 1995, pp. 438–441.

- ^ Cook & Stevenson 2006, p. 21

- ^ Klovland 2017, pp. 50–54.

References

- Cook, Chris; Stevenson, John (2006). The Routledge Companion to World History since 1914. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-28178-7.

- Grey, Edwyn (1972). The Killing Time: The U-boat War, 1914–18. London: Seeley. ISBN 978-0-85422-070-0.

- Halpern, Paul (1995). A Naval History of World War I. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-85728-498-0.

- Halsey, Francis Whiting (1919). History of the World War: Compiled from Original and Contemporary Sources: American, British, French, German, and others. Vol. IX. New York: Funk & Wagnalls Company. OCLC 312834.

- Holwitt, Joel I. (2009). "Execute Against Japan": The U.S. Decision to Conduct Unrestricted Submarine Warfare. Williams-Ford Texas A&M University military history series (No. 121). College Station: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-1-60344-083-7. Retrieved 26 August 2024 – via Archive Foundation.

- Klovland, Jan T. (2017). "Navigating through torpedo attacks and enemy raiders: Merchant shipping and freight rates during World War 1" (PDF). Norwegian School of Economics (NHH). ISSN 0804-6824. Retrieved 26 August 2024.

- Lundeberg, Philip K. (1963). "The German Naval Critique of the U-Boat Campaign, 1915–1918". Military Affairs. 27 (3). doi:10.2307/1984204. ISSN 0026-3931. JSTOR 1984204.

- Manson, Janet Marilyn (1977). International law, German Submarines and American Policy (Thesis). Portland State University. Department of History. doi:10.15760/etd.2489. 2492. Retrieved 26 August 2024.

- McKee, Fraser M. (January 1993). "An Explosive Story: The Rise and Fall of the Depth Charge". The Northern Mariner. III (1). Grafton, ON: Canadian Nautical Research Society: 45–58. ISSN 1183-112X.

- Messimer, Dwight (2001). Find and Destroy: Antisubmarine Warfare in World War I. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-447-0.

- Messimer, Dwight R. (2002). Verschollen: World War I U-boat losses. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-475-3.

- Prendergast, Maurice; Gibson, R.H. (2002). The German Submarine War, 1914–1918. Penzance: Periscope Publishing. ISBN 978-1-904381-08-2.

- Stead, W. T. (1901). The Americanization of the World. New York: Horace Markley. OCLC 458560597. Retrieved 16 August 2024 – via Archive Foundation.

- Tarrant, V.E. (1989). The U-Boat Offensive 1914–1945. London: Arms and Armour. ISBN 978-0-85368-928-7.

Further reading

- Kemp, Paul (1997). U-Boats Destroyed. London: Arms and Armour. ISBN 978-1-85409-515-2.

External links

- Abbatiello, John: Atlantic U-boat Campaign, in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

- Karau, Mark D.: Submarines and Submarine Warfare, in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.