Atlantic Puffins

The Atlantic puffin (Fratercula arctica), also known as the common puffin, is a species of seabird in the auk family. It is the only puffin native to the Atlantic Ocean; two related species, the tufted puffin and the horned puffin being found in the northeastern Pacific. The Atlantic puffin breeds in Russia, Iceland, Ireland, Britain, Norway, Greenland, Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, and the Faroe Islands, and as far south as Maine in the west and France in the east. It is most commonly found in the Westman Islands, Iceland. Although it has a large population and a wide range, the species has declined rapidly, at least in parts of its range, resulting in it being rated as vulnerable by the IUCN. On land, it has the typical upright stance of an auk. At sea, it swims on the surface and feeds on zooplankton, small fish, and crabs, which it catches by diving underwater, using its wings for propulsion.

This puffin has a black crown and back, light grey cheek patches, and a white body and underparts. Its broad, boldly marked red-and-black beak and orange legs contrast with its plumage. It moults while at sea in the winter, and some of the brightly coloured facial characteristics are lost, with colour returning during the spring. The external appearances of the adult male and female are identical, though the male is usually slightly larger. The juvenile has similar plumage, but its cheek patches are dark grey. The juvenile does not have brightly coloured head ornamentation, its bill is narrower and is dark grey with a yellowish-brown tip, and its legs and feet are also dark. Puffins from northern populations are typically larger than in the south and these populations are generally considered a different subspecies.

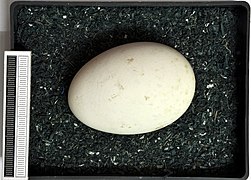

Spending the autumn and winter in the open ocean of the cold northern seas, the Atlantic puffin returns to coastal areas at the start of the breeding season in late spring. It nests in clifftop colonies, digging a burrow in which a single white egg is laid. Chicks mostly feed on whole fish and grow rapidly. After about 6 weeks, they are fully fledged and make their way at night to the sea. They swim away from the shore and do not return to land for several years.

Colonies are mostly on islands with no terrestrial predators, but adult birds and newly fledged chicks are at risk of attacks from the air by gulls and skuas. Sometimes, a bird such as an Arctic skua or blackback gull can cause a puffin arriving with a beak full of fish to drop all the fish the puffin was holding in its mouth. The puffin's striking appearance, large, colourful bill, waddling gait, and behaviour have given rise to nicknames such as "clown of the sea" or "sea parrot". It is the official bird of the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador.

Taxonomy and etymology

| Cladogram of the family Alcidae |

The Atlantic puffin is a species of seabird in the order Charadriiformes. It is in the auk family, Alcidae, which includes the guillemots, typical auks, murrelets, auklets, puffins, and the razorbill. The rhinoceros auklet (Cerorhinca monocerata) and the puffins are closely related, together composing the tribe Fraterculini. The Atlantic puffin is the only species in the genus Fratercula to occur in the Atlantic Ocean. Two other species are known from the northeast Pacific, the tufted puffin (Fratercula cirrhata) and the horned puffin (Fratercula corniculata), the latter being the closest relative of the Atlantic puffin.

The generic name Fratercula comes from the Medieval Latin fratercula, friar, a reference to their black and white plumage, which resembles monastic robes. The specific name arctica refers to the northerly distribution of the bird, being derived from the Greek ἄρκτος (arktos), the bear, referring to the northerly constellation, the Ursa Major (Great Bear). The vernacular name "puffin" – puffed in the sense of swollen – was originally applied to the fatty, salted meat of young birds of the unrelated species Manx shearwater (Puffinus puffinus), which in 1652 was known as the "Manks puffin". It is an Anglo-Norman word (Middle English pophyn or poffin) used for the cured carcasses. The Atlantic puffin acquired the name at a much later stage, possibly because of its similar nesting habits, and it was formally applied to Fratercula arctica by Pennant in 1768. While the species is also known as the common puffin, "Atlantic puffin" is the English name recommended by the International Ornithological Congress.

The three subspecies generally recognized are:

- F. a. arctica

- F. a. grabae

- F. a. naumanni

The only morphological difference between the three is their size. Body length, wing length, and size of beak all increase at higher latitudes. For example, a puffin from northern Iceland (subspecies F. a. naumanii) weighs about 650 g (1 lb 7 oz) and has a wing length of 186 mm (7+5⁄16 in), while one from the Faroes (subspecies F. a. grabae) weighs 400 g (0.9 lb) and has a wing length of 158 mm (6.2 in). Individuals from southern Iceland (subspecies F. a. arctica) are intermediate between the other two in size. Ernst Mayr has argued that the differences in size are clinal and are typical of variations found in the peripheral population and that no subspecies should be recognised.

Description

The Atlantic puffin is sturdily built with a thick-set neck and short wings and tail. It is 28 to 30 cm (11 to 12 in) in length from the tip of its stout bill to its blunt-ended tail. Its wingspan is 47 to 63 cm (19 to 25 in) and on land it stands about 20 cm (8 in) high. The male is generally slightly larger than the female, but they are coloured alike. The forehead, crown, and nape are glossy black, as are the back, wings, and tail. A broad, black collar extends around the neck and throat. On each side of the head is a large, lozenge-shaped area of very pale grey. These face patches taper to a point and nearly meet at the back of the neck. The shape of the head creates a crease extending from the eye to the hindmost point of each patch, giving the appearance of a grey streak. The eyes look almost triangular because of a small, peaked area of horny blue-grey skin above them and a rectangular patch below. The irises are brown or very dark blue, and each has a red orbital ring. The underparts of the bird, the breast, belly, and under tail coverts, are white. By the end of the breeding season, the black plumage may have lost its shine or even taken on a slightly brown tinge. The legs are short and set well back on the body, giving the bird its upright stance when on land. Both legs and large webbed feet are bright orange, contrasting with the sharp, black claws.

The beak is very distinctive. From the side, the beak is broad and triangular, but viewed from above, it is narrow. The half near the tip is orange-red and the half near the head is slate grey. A yellow, chevron-shaped ridge separates the two parts, with a yellow, fleshy strip at the base of the bill. At the joint of the two mandibles is a yellow, wrinkled rosette. The exact proportions of the beak vary with the age of the bird. In an immature individual, the beak has reached its full length, but it is not as broad as that of an adult. With time the bill deepens, the upper edge curves, and a kink develops at its base. As the bird ages, one or more grooves may form on the red portion. The bird has a powerful bite.

The characteristic bright orange bill plates and other facial characteristics develop in the spring. At the close of the breeding season, these special coatings and appendages are shed in a partial moult. This makes the beak appear less broad, the tip less bright, and the base darker grey. The eye ornaments are shed and the eyes appear round. At the same time, the feathers of the head and neck are replaced and the face becomes darker. This winter plumage is seldom seen by humans because when they have left their chicks, the birds head out to sea and do not return to land until the next breeding season. The juvenile bird is similar to the adult in plumage, but altogether duller with a much darker grey face and yellowish-brown beak tip and legs. After fledging, it makes its way to the water and heads out to sea, and does not return to land for several years. In the interim, each year, it will have a broader bill, paler face patches, and brighter legs and beaks.

The Atlantic puffin has a direct flight, typically 10 m (35 ft) above the sea surface and higher over the water than most other auks. It mostly moves by paddling along efficiently with its webbed feet and seldom takes to the air. It is typically silent at sea, except for the soft purring sounds it sometimes makes in flight. At the breeding colony, it is quiet above ground, but in its burrow makes a growling sound somewhat resembling a chainsaw being revved up.

Distribution

The Atlantic puffin is a bird of the colder waters of the North Atlantic Ocean. It breeds on the coasts of northwest Europe, the Arctic fringes, and eastern North America. More than 90% of the global population is found in Europe (4,770,000–5,780,000 pairs, equalling 9,550,000–11,600,000 adults) and colonies in Iceland alone are home to 60% of the world's Atlantic puffins. The largest colony in the western Atlantic (estimated at more than 260,000 pairs) can be found at the Witless Bay Ecological Reserve, south of St. John's, Newfoundland and Labrador. Other major breeding locations include the north and west coasts of Norway, the Faroe Islands, Shetland and Orkney, the west coast of Greenland, and the coasts of Newfoundland. Smaller-sized colonies are also found elsewhere in the British Isles, the Murmansk area of Russia, Novaya Zemlya, Spitzbergen, Labrador, Nova Scotia, and Maine. Islands seem particularly attractive to the birds for breeding as compared to mainland sites, likely to avoid predators.

While at sea, the bird ranges widely across the North Atlantic Ocean, including the North Sea, and may enter the Arctic Circle. In the summer, its southern limit stretches from northern France to Maine; in the winter, the bird may range as far south as the Mediterranean Sea and North Carolina. These oceanic waters have such a vast extent of 15×10–30×10 km (6×10–12×10 sq mi) that each bird has more than 1 km of range at its disposal, so is seldom seen out at sea. In Maine, light-level geolocators have been attached to the legs of puffins, which store information on their whereabouts. The birds need to be recaptured to access the information, a difficult task. One bird was found to have covered 7,700 km (4,800 mi) of the ocean in 8 months, traveling northwards to the northern Labrador Sea then southeastward to the mid-Atlantic before returning to land.

In a long-living bird with a small clutch size, such as the Atlantic puffin, the survival rate of adults is an important factor influencing the success of the species. Only 5% of the ringed puffins that failed to reappear at the colony did so during the breeding season. The rest were lost some time between departing from land in the summer and reappearing the following spring. The birds spend the winter widely spread out in the open ocean, though a tendency exists for individuals from different colonies to overwinter in different areas. Little is known of their behaviour and diet at sea, but no correlation was found between environmental factors, such as temperature variations, and their mortality rate. A combination of the availability of food in winter and summer probably influences the survival of the birds, since individuals starting the winter in poor condition are less likely to survive than those in good condition.

Behaviour

Like many seabirds, the Atlantic puffin spends most of the year far from land in the open ocean and only visits coastal areas to breed. It is a sociable bird and it usually breeds in large colonies.