Bairat Temple

It is situated in the ancient region of Matsya Janpad, a centre of vedic sacrifices in early literary and epigraphic references. Thus evidence of a flourishing Buddhist centre from this region is very significant. Bairat temple has been given attention by several archaeologists such as Cunningham and later by Carlleyle, Bhandarkar and Dayaram Sahni. The significant structures at the site of Bairat include a monastery and numerous remnants of Asokan pillars beside the circular temple.

Circular Temple and Artefacts at Bairat

The circular temple is constructed on the lower platform. It is surrounded by a circumambulatory path. It is a structural temple that had made use of fire burnt bricks. It has crevices that indicate that it was surrounded by wooden pillars. The lime-plastered panels of brickwork in the shrine alternate with twenty-six octagonal pillars of wood. It shows two circles in plan and has no precedent of the kind. Dayaram Sahni has suggested that Bairat temple is the oldest structural temple and it served as model for the numerous rock-cut temples of Western and Eastern India. The monastery attached to the shrine is elaborate with cells being large enough to accommodate just a single monk or nun. It is situated on the upper platform. Many portable antiquities like pottery jars, lamps etc have also been found on the site. All the evidence indiacate that Bairat temple was highly revered in the contemporary Buddhist world.

Sahni suggests that the elaborate structures indicate sincreasing visibility of Buddhist sites. The remarkable presence of structures like the Bairat temple can be linked to increasing popularity of Buddhism at the time. Mauryan king Asoka's support and interest led to extraordinary development of Buddhist art. It appears that Rajasthan did not remain untouched with this wave of Buddhism. The sangharam of Bairat and the circular stupa at the Bijak hills were definitely majestic. They evidence that Buddhism existed here in a developed stage.

A rare circular stand-alone temple

Early Chaitya halls are known from the 3rd century BCE. They generally followed a circular or apsidal plan, and were either rock-cut or freestanding. Temples —built on elliptical, circular, quadrilateral, or apsidal plans— were initially constructed using brick and timber. Some temples of timber with wattle-and-daub may have preceded them, but none remain to this day.

Today, only the foundation of the temple remains. The circular temple was located inside a rectangular enclosure wall, and had an outer diameter of 5.6 meters. It was built around a small stupa at the centre, with a diameter of 1.6 meters. There was also an internal circle of 26 wooden octagonal columns surrounding the stupa. The layout created two pradaksina circular paths for devotional deambulation. The global shape of the temple has been inferred from more or less contemporary reliefs of such buildings from Bharhut, or from rock-cut temples at Kondivite, Tulja Caves or Guntupalli Caves.

It has been suggested that this circular design with columns was derived from the similar design of the Greek Tholos. However local circular hut designs are a more probable source of inspiration.

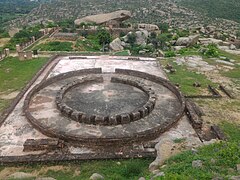

-

Another view of the remains.

-

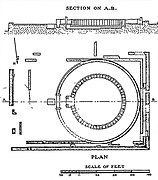

Temple plan.

-

Drawing of original temple

-

Relief of a circular temple, Bharhut, circa 100 BCE.

-

Early circular Mahabodhi Temple, Bharhut, circa 100 BCE.

Minor Rock Edict of Ashoka

A Minor Rock Edict of Ashoka (the unique Minor Rock Edict No.3) was found in close proximity to the Temple: the Bairat-Calcutta Edict, also called the Bhabru Edict, from the name of a nearby village. Dating to circa 250 BCE, the edict was found just in front of the remains of the Bairat Temple, on the lower platform located between the temple and the cannon-shaped large rock, by Major Burt in 1840 (27°25′02″N 76°09′45″E / 27.417124°N 76.162569°E). The presence of this inscription, its date and its Buddhist content, help date the temple with a high level of certainty, as well as confirm its Buddhist affiliation.

The Edict, relocated since the 19th century to the Asiatic Society of Bengal in Calcutta (hence the name "Calcutta-Bairat Edict)", is the only one of its kind, describing Buddhist scriptures recommended by Ashoka for study. It reads:

The Magadha King Priyadarsin, having saluted the Samgha hopes they are both well and comfortable.

It is known to you, Sirs, how great is my reverence and faith in the Buddha, the Dharma (and) the Samgha.

Whatsoever, Sirs, has been spoken by the blessed Buddha, all that is quite well spoken.

But, Sirs, what would indeed appear to me (to be referred to by the words of the scripture): "thus the true Dharma will be of long duration", that I feel bound to declare:

The following expositions of the Dharma, Sirs, (viz.) the Vinaya-Samukasa ("The Exaltation of Discipline"), the Aliya-vasas ("The Ideal Mode of Life"), the Anagata-bhayas ("Fears to Come"), the Muni-gathas ("The Songs of the Hermit"), the Moneya-Suta ("Discourse on the Hermit Life"), the Upatisa-pasina ("The Questions of Upatishya"), and the Laghulovada ("The Sermon to Rahula") which was spoken by the blessed Buddha concerning falsehood, — I desire, Sirs, that many groups of monks and (many) nuns may repeatedly listen to these expositions of the Dharma and may reflect (on them).

In the same way both laymen and laywomen (should act).

For the following (purpose), Sirs, am I causing this to be written, (viz.) in order that they may know my intention.

— Adapted from Inscriptions of Asoka. New Edition by E. Hultzsch 1925 p.172 Public Domain

This edict was the basis for the efforts at deciphering Brahmi, led by James Prinsep in 1837. A commemorative plaque is visible at the Asiatic Society.

The inscription of Asoka found from this region addresses the Buddhist monks. There must have been a considerable presence of the Buddhist monks in Bairat. But the centre must have declined in later period and a change in situation is recorded in the travelogue of Hieun-tsang who wrote that the popularity of Buddhism in Bairat was not what he had imagined it to be.

Other circular temples

Some of the earliest free-standing temples may have been of a circular type. Ashoka also built the Mahabodhi Temple in Bodh Gaya circa 250 BCE, also a circular structure, in order to protect the Bodhi tree under which the Buddha had found enlightenment. Representations of this early temple structure are found on a 100 BCE relief sculpted on the railing of the stupa at Bhārhut, as well as in Sanchi. From that period the Diamond throne remains, an almost intact slab of sandstone decorated with reliefs, which Ashoka had established at the foot of the Bodhi tree. These circular-type temples were also found in later rock-hewn caves such as Tulja Caves or Guntupalli.

-

Bodhi tree temple depicted in Sanchi, Stupa 1, Southern gateway.

-

Relief of a multi-storied temple, 2nd century CE, Ghantasala Stupa.

-

Remains of the circular rock-hewn circular Chaitya with columns, Tulja Caves.

Apsidal temples

Another early free-standing temple in India, this time apsidal in shape, appears to be Temple 40 at Sanchi, which is also dated to the 3rd century BCE. It was an apsidal temple built of timber on top of a high rectangular stone platform, 26.52x14x3.35 metres, with two flights of stairs to the east and the west. The temple was burnt down sometime in the 2nd century BCE. This type of apsidal structure was also adopted for most of the cave temple (Chaitya-grihas), as in the 3rd century BCE Barabar Caves and most caves thereafter, with side, and then frontal, entrances. A freestanding apsidal temple remains to this day, although in a modified form, in the Trivikrama Temple in Ter, Maharashtra.

See also

References

- ^ "ASI Notice". Archived from the original on 30 August 2018. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- ^ Cunningham, Sir Alexander (1871). Archaeological Survey Of India Four Reports Made During The Years 1862 - 63 - 64 - 65 Volume Ii. pp. 242–248. Archived from the original on 31 October 2023. Retrieved 31 October 2023.

- ^ Le Huu Phuoc, 2010, p.233-237

- ^ Chaturvedi, Neekee (2012). "Evolution of Buddhism in Rajasthan". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 73: 155–162. ISSN 2249-1937. JSTOR 44156201. Archived from the original on 1 April 2023. Retrieved 31 October 2023.

- ^ "Archaeological Remains and Excavations at Bairat". INDIAN CULTURE. Archived from the original on 1 April 2023. Retrieved 1 April 2023.

- ^ Chakrabarty, Dilip K. (2009). India: An Archaeological History: Palaeolithic Beginnings to Early Historic Foundations. Oxford University Press. p. 421. ISBN 9780199088140. Archived from the original on 31 October 2023. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- ^ Chandra (2008)

- ^ "According to Cunningham this is probably the same inscription of Ashoka which Major Burt found in 1840 on a hill at Bairat." in Misra, Virendra N. (2007). Rajasthan: Prehistoric and Early Historic Foundations. Aryan Books International. p. 47. ISBN 978-81-7305-321-4. Archived from the original on 31 October 2023. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- ^ Cunningham, Alexander (1871). Archaeological Survey Of India Vol. 2. p. 247.

- ^ Smith, Vincent E. (2018). Asoka: The Buddhist Emperor. Sristhi Publishers & Distributors. p. 104. ISBN 978-93-87022-26-3. Archived from the original on 31 October 2023. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- ^ Proceedings of the Meetings of the Session, Volume 24, Indian Historical Records Commission, 1948 "the discovery at Bairat of the Asokan inscription which, in the hands of James Prinsep, became the key for unravelling and deciphering the edicts of King Piyadasi"

- ^ "Sowing the Seeds of the Lotus: A Journey to the Great Pilgrimage Sites of Buddhism, Part I" by John C. Huntington. Orientations, November 1985 pg 61

- ^ Buddhist Architecture, Huu Phuoc Le, Grafikol, 2010 p.240

- ^ A Global History of Architecture, Francis D. K. Ching, Mark M. Jarzombek, Vikramaditya Prakash, John Wiley & Sons, 2017 p.570ff Archived 2 July 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hardy, Adam (1995). Indian Temple Architecture: Form and Transformation: the Karṇāṭa Drāviḍa Tradition, 7th to 13th Centuries. Abhinav Publications. p. 39. ISBN 9788170173120. Archived from the original on 31 October 2023. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- ^ Le, Huu Phuoc (2010). Buddhist Architecture. Grafikol. p. 238. ISBN 9780984404308. Archived from the original on 31 October 2023. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- ^ Buddhist Architecture, Lee Huu Phuoc, Grafikol 2010, p.147

- ^ Abram, David; (Firm), Rough Guides (2003). The Rough Guide to India. Rough Guides. ISBN 9781843530893. Archived from the original on 31 October 2023. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- ^ Marshall, John (1955). Guide to Sanchi.

- ^ Le, Huu Phuoc (2010). Buddhist Architecture. Grafikol. p. 237. ISBN 9780984404308. Archived from the original on 31 October 2023. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

Sources

- Chandra, Pramod (2008), South Asian arts, Encyclopædia Britannica.

![Relief of a multi-storied temple, 2nd century CE, Ghantasala Stupa.[15][16]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/75/Andhra_pradesh%2C_santuario_a_pi%C3%B9_piani%2C_da_ghantasala%2C_90-110_ca..JPG/120px-Andhra_pradesh%2C_santuario_a_pi%C3%B9_piani%2C_da_ghantasala%2C_90-110_ca..JPG)