Balcón De Montezuma

This Huastec site is located some 203 kilometres (126.1 mi) north-west from the Las Flores Huastec archaeological site.

Background

According to paleontological and archaeological records, the earliest settlements in Tamaulipas are dated to twelve thousand years before the Christian era, and are identified in the so-called "complex Devil", in allusion to a Canyon of the Sierra of Tamaulipas. Later, at the Tropic of cancer level, are the first manifestations of native civilization, linked to the discovery and domestication of corn and thus to the beginning of agricultural life and the grouping of permanent settlements. As a result, in this period began to appear manifestations of Mesoamerican cultures in this region.

Before the arrival of the Spanish invaders, the Tamaulipas territory was occupied by various ethnic groups, one of them were the Wasteks. Américo Vespucio, famous Italian cartographer after whom the American continents were named, visited the Tamaulipas territory at the end of the 16th century and in his correspondence with Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco mentioned that the natives called the territory "lariab". During colonial times was known by other names: "Kingdom Guasteca, province of Amichel and Earth Garayana, Pánuco province, Comarca of Paul, Alifau and Ocinan, Magdalena Medanos and "New Santander". The current name comes from the founding "Tamaholipa" by Fray Andrés de Olmos in 1544.

In Tamaulipas, the Huastecs settled primarily along the lower basin of the Guayalejo River-Tamesí and in mountain valleys of Tanguanchín (Ocampo) and Tammapul (Tula). Politically they did not seem to constitute a State, but rather a series of Lordships. They were skilled craftsmen and possessed a complex religious cosmogony, insomuch that in the Huasteca emerged the concept of the Quetzalcoatl deity. As a culture located in a peripheral area of nuclear Mesoamerica, they held a long autonomy until in the late postclassical period the Mexicas subjected them to their domain to a portion of the Huasteca.

Other Huastec settlements with a great constructive work, are evident in the Balcón de Montezuma, an archaeological site located in the vicinity of the present capital of the State.

The Huastec culture large geographical development above is evident by the many sites scattered throughout the almost impenetrable mountains, as it is the case of the Sabinito, an interesting site currently in research, which speaks of an organized society of Mesoamerican type. However, there is evidence that during the postclassical period this cultural model was depleted, leaving the sierra inhabited by various groups of farmers, but of a lesser civilization level.

Cultural development

In the Tamaulipas sierras, three mesoamerican related archaeological phases are present; Laguna, Eslabones and Salta, covering a chronological period from 650 BCE to 1000 CE.

It had an initial cultural Pantheon defined by a constant evolution and the emergence of scattered villages between the sierra that concentrated up to 400 homes located around squares and platforms; and small circular base structures. But it was around 500 CE when this culture reached its peak, to expand urban concentrations up to a thousand houses, which formed villages in the peaks of the hills, with a central core of small pyramids. Simple urban planning suggests the existence of a possibly theocratic and centralized government, and pottery indicate trade with the nuclear area of Mesoamerica.

The Huastecs

The Huastec, also known as Huaxtec, Wastek and Huastecos, are a native group of Mexico, historically based in the states of Hidalgo, Veracruz, San Luis Potosí and Tamaulipas concentrated along the route of the Pánuco River and along the coast of the Gulf of Mexico.

The ancient Huastec culture is thought to date back to approximately the 10th century BCE, although their most productive period of civilization is usually considered to be the Postclassic era between the fall of Teotihuacan and the rise of the Aztec Empire. The Huastecs constructed temples on step-pyramids, carved independently-standing sculptures, and produced elaborately painted pottery.

The Huastecs attained an important culture and built cities, yet usually wore no clothing. They were admired for their abilities as musicians by other Mesoamerican peoples.

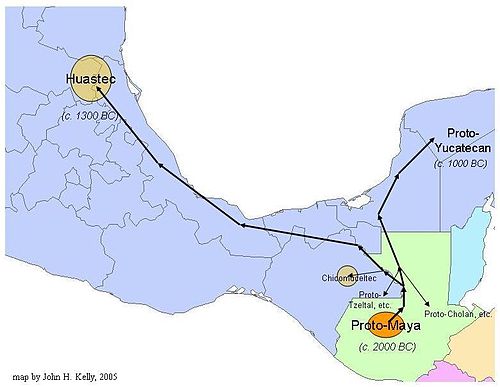

The Huastecs arrived in northern Mesoamerica between 1500 BCE and 900 BCE. The linguistic evidence is corroborated by archaeological discoveries. In 1954, Richard Stockton MacNeish found ceramics and figurines from the mid-preclassical (Formative) period, called "Pavon de Panuco" in the Panuco River sites of the Huasteca, which resemble preclassical period objects from Uaxactun, a Petén-region Maya site. A date not earlier than 1100 BCE for the Huastecs' arrival at their present location seems most likely, since they probably did not arrive at the north-central Veracruz site of Santa Luisa until about 1200 BCE, the phase at the end of the early preclassical period known locally as the "Ojite phase". Artifacts of the period include Panuco-like basalt manos and metates. The Huastecs remained in Santa Luisa, located east of Papantla near the Gulf coast, until supplanted or absorbed by the Totonacs around 1000 CE.

Huastec language

The Wastek or Huastec language is a Mayan language of Mexico, spoken by the Huastecs. Though relatively isolated from them, it is related to the Mayan languages spoken further south and east in Mexico and Central America.

The language is called Teenek (with varying spellings) by its speakers, and this name has gained currency in Mexican national and international usage in recent years.

The now-extinct Chicomuceltec language is believed to have been most closely related to Wastek.

The first linguistic description of the Huastec language accessible to Europeans was written by Andrés de Olmos, who also wrote the first grammatical descriptions of Nahuatl and Totonac.

Toponymy

The name Tamaulipas (Spanish pronunciation: [tamawˈlipas]) is probably derived from Tamaholipa, a Huastec term in which the tam- prefix signifies "place where." As yet, there is no scholarly agreement on the meaning of holipa, the native population of Tamaulipas, now extinct, was referred to as the "Olives"

Tamaulipas probably means "Montes Altos" (high hills). Another version states that means "Place of olives", natives originating in Florida, USA.

Site Investigation

This site was explored and restored between 1989 and 1990, by archaeologist Jesus Nárez. Based on the research, it is known that ancient houses found at the site—hut style with palm roofs—were built on top of the circular bases while their dead was buried under the floors. In the 1980s numerous human skeletal remains were found, both children and adults.

Balcón de Montezuma is representative of small farming villages of the sierra that originated in the Late Classic period (600–900 CE) of Mesoamerican chronology.

The site

This site represents a village (400–1200CE) composed of around 90 circular bases distributed in two plazas; and is located in the Sierra Madre Oriental range, at an altitude of 1,200 metres (3,937 ft) above mean sea level.

The site contains vestiges and architectonic styles of human groups that inhabited the Sierra Madre Oriental (Sierra Gorda) region and the Sierra de Tamaulipas, whose culture and the Mesoamerican profile shares features of the Huastec culture and the Southwestern United States.

So far no representations of their gods have been found, nor it is known if any of the buildings functioned as temples. The original entrance to the site was via a large stairway of more than 80 steps located on the western hillside; it was built as an adaptation to natural limestone hill protrusions.

Structures

The site comprises more than 70 circular structures of different diameters and heights grouped into two small semi-circular plazas. These bases were built with limestone, overlaid without mortar, the core is made up of dirt, small stones and pottery remains. The site displays unique characteristics, such as a small stairway with 3 to 4 steps, recessed or superimposed, with a fan-shaped base. It is thought that the bases were houses circular foundations, with bajareque walls and palm leaf roofs.

The archaeological remains have traces of stone slabs paved surfaces.

Archaeological material found at the site revealed practices of its people such as smoking pipes, using crystal quartz – perhaps as amulets-, necklaces, stone disks and burial of the dead under the floor of the House, accompanied by ceramic offerings.

See also

References

- ^ "Turismo Arqueologico en Tamaulipas" [Archaeological tourism in Tamaulipas] (in Spanish). Visiting Mexico. Archived from the original on 11 August 2010.

- ^ Kaufman, p. 106

- ^ Stresser-Pean

- ^ Ochoa, p. 42

- ^ Wilkerson, p. 897

- ^ Wilkerson, p. 892

- ^ "Tamaulipas y Tampico" (in Spanish). Enciclopedia de los Municipios de México.

- ^ "Work continued at Balcón de Montezuma" (in Spanish). Arts & History. Archived from the original on 19 July 2011.

- ^ "Balcón de Montezuma Official Web Page" (in Spanish). INAH. Archived from the original on 10 September 2010.

Bibliography

- Ariel de Vidas, A. 2003. "Ethnicidad y cosmologia: La construccion cultural de la diferencia entre los teenek (huaxtecos) de Veracruz", in UNAM, Estudios de Cultura Maya. Vol. 23.

- Campbell, L. and T. Kaufman. 1985. "Maya linguistics: Where are we now?," in Annual Review of Anthropology. Vol. 14, pp. 187–98

- Dahlin, B. et al. 1987. "Linguistic divergence and the collapse of Preclassic civilization in southern Mesoamerica". American Antiquity. Vol. 52, No. 2, pp. 367–82.

- INAH. 1988. Atlas cultural de Mexico: Linguistica. Mexico City: Instituto Nacional de Antropologia e Historia.

- Kaufman, T. 1976. "Archaeological and linguistic correlations in Mayaland and associated areas of Mesoamerica." World Archaeology 8:101–18.

- Malstrom, V. 1985. "The origins of civilization in Mesoamerica: A geographic perspective", in L. Pulsipher, ed. Yearbook of the Conference of Latin Americanist Geographers. Vol. 11, pp. 23–29.

- Ochoa, L. 2003. "La costa del Golfo y el area maya: Relaciones imaginables o imaginadas?", in UNAM, Estudios de Cultura Maya. Vol. 23.

- Robertson, J. 1993. "The origins and development of Huastec pronouns." International Journal of American Linguistics. 59(3):294–314

- Stresser-Pean, G. 1989. "Los indios huastecos." In Huastecos y Totonacas, edited by L. Ochoa. Mexico City: CONACULTA.

- Vadillo Lopez, C. and C. Riviera Ayala. 2003. "El tráfico marítimo, vehículo de relaciones culturales entre la región maya chontal de Laguna de Términos y la región huaxteca del norte de Veracruz, siglos XVI-XIX", in UNAM, Estudios de Cultura Maya. Vol. 23.

- Wilkerson, J. 1972. Ethnogenesis of the Huastecs and Totonacs. PhD dissertation, Department of Anthropology and Archaeology, Tulane University, New Orleans.

- E. B. Tylor, "On the Game of Patolli in Ancient Mexico, and Its Probably Asiatic Origin" (Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland) Vol. 8, 1879), pp. 116–129.

- E. B. Tylor, "American Lot Games as Evidence of Asiatic Intercourse before the Time of Columbus" (Internationales Archie fur Ethnogrophie, Vol. 9, supplement, 1896), p. 66. For a critical evaluation of Tylor's method, see C. J. Erasmus, "Patolli, Pachisi, and the Limitation of Possibilities" (Southwestern Journal of Anthropology, Vol. 6, 1950), pp. 369–387.

- F. Boas, Tsimshian Mythology (Bureau of American Ethnology, Annual Report 31, 1916), pp. 393–558. This is the classic study of the reflection of a people's material culture and social organization in their mythology.

Further reading

- Ariel de Vidas, A. 2003. "Etnicidad y cosmología: La construcción cultural de la diferencia entre los teenek (huaxtecos) de Veracruz", in UNAM, Estudios de Cultura Maya. Vol. 23.

- Campbell, L. and T. Kaufman. 1985. "Maya linguistics: Where are we now?," in Annual Review of Anthropology. Vol. 14, pp. 187–98

- Dahlin, B. et al. 1987. "Linguistic divergence and the collapse of Preclassic civilization in southern Mesoamerica". American Antiquity. Vol. 52, No. 2, pp. 367–82.

- INAH. 1988. Atlas cultural de Mexico: Linguistica. Mexico City: Instituto Nacional de Antropologia e Historia.

- Kaufman, T. 1976. "Archaeological and linguistic correlations in Mayaland and associated areas of Mesoamerica," in World Archaeology. Vol. 8, pp. 101–18

- Malstrom, V. 1985. "The origins of civilization in Mesoamerica: A geographic perspective", in L. Pulsipher, ed. Yearbook of the Conference of Latin Americanist Geographers. Vol. 11, pp. 23–29.

- (CDI). No date. San Luis Potosí: A Teenek Profile; Summary.

- Ochoa, L. 2003. "La costa del Golfo y el area maya: Relaciones imaginables o imaginadas?", in UNAM, Estudios de Cultura Maya. Vol. 23.

- Robertson, J. 1993. "The origins and development of Huastec pronouns." International Journal of American Linguistics. Vol. 59, No. 3, pp. 294–314

- Stresser-Pean, G. 1989. "Los indios huastecos", in Ochoa, L., ed. Huastecos y Totonacas. Mexico City: CONACULTA.

- Vadillo Lopez, C. and C. Riviera Ayala. 2003. "El trafico marítimo, vehículo de relaciones culturales entre la región maya chontal de Laguna de Términos y la región huasteca del norte de Veracruz, siglos XVI-XIX", in UNAM, Estudios de Cultura Maya. Vol. 23.

- Wilkerson, J. 1972. Ethnogenesis of the Huastecs and Totonacs. PhD dissertation, Department of Anthropology and Archaeology, Tulane University, New Orleans.

External links

- Tampico municipal government Official website (in Spanish)

- Tamaulipas state government. (in Spanish)

- Ciudad Victoria Municipal government official web page (in Spanish)