Banner Of Poland

Derived from early flag-like objects, the Polish royal banner of arms dates as far back as the 11th century. A symbol of royal authority, it was used at coronations and in battles. In the interwar period, it was replaced with the Banner of the Republic of Poland, which was part of the presidential insignia. A national banner is not mentioned in the current (2007) regulations on Polish national symbols, although today's presidential jack is based directly on the pre-war design for the Banner of the Republic.

History

From stanica to chorągiew

The banner of Poland traces its origins to the ancient vexilloids known as stanice (pronounced [staˈɲit͡sɛ]; singular: stanica), probably used at least as early as the 10th century. Although no specimens or images are preserved, a stanica was probably a cloth draped vertically from a horizontal crosspiece attached to a wooden pole or spear, resembling the Roman vexillum. It was both a religious and military symbol; the stanice were kept either inside or outside pagan temples in peacetime and were taken to war as military insignia.

With Poland's conversion to Christianity in the late 10th century, the pagan stanice were probably Christianized by replacing pagan symbols with Christian ones such as images of patron saints, or a Chi-Rho or dove symbolizing the Holy Spirit. In the year 1000, during his pilgrimage to the tomb of Saint Adalbert in Gniezno, the capital of Poland until about 1040, Emperor Otto III officially recognized Duke Boleslaus the Brave as King of Poland (see Congress of Gniezno), crowning him and presenting him with a replica of the Holy Lance, also known as Saint Maurice's Spear. This relic, together with the vexillum attached to it, was probably the first insignia of the nascent Kingdom of Poland, a symbol of King Boleslaus's rule, and of his allegiance to the Emperor. It remains unknown what images, if any, were painted or embroidered on the vexillum.

A royal banner was used as early as the reign of Boleslaus the Generous (r. 1076-1079). The earliest mention of a banner (Polish: chorągiew, pronounced [xɔˈrɔŋɡʲɛf]) bearing the sign of an eagle is found in Wincenty Kadłubek's Chronicle which says that Duke Casimir the Just fought the Ruthenians in 1182 "under the sign of the victorious eagle". A seal of Duke Premislaus II from 1290 shows the ruler holding a banner emblazoned with a crowned eagle. Five years later, Premislaus was crowned King of Poland, and his crowned white eagle became the royal coat of arms of Poland. During the reign of King Ladislaus the Elbow-High (r. 1320–1333), the red cloth with the White Eagle was finally established as the Banner of the Kingdom of Poland (Polish: chorągiew Królestwa Polskiego). The orientation of the eagle on the banner varied; its head could point either upwards or towards the hoist. The actual rendering of the eagle changed with time according to new artistic styles.

The national banner was identical with that of Lesser Poland, the territory where Kraków, the capital of Poland until 1596, is located. It was therefore carried by the Standard-bearer of Kraków until that office was replaced by the Grand Standard-Bearer of the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland (Polish: chorąży wielki koronny, Latin: vexillifer regni).

Polish–Lithuanian union

One of the most famous standard-bearers of Kraków was Marcin of Wrocimowice (d. 1442) who carried the national banner in the Battle of Grunwald (Tannenberg) in 1410. The military unit (chorągiew) that went to the battle under that banner comprised the elite of Polish knights, including such chivalrous celebrities as Zawisza the Black, which is a clear sign that the banner, described by the chronicler Jan Długosz as "the great banner of Kraków Territory", was also the insignia of the entire kingdom. During the course of the battle, according to Długosz, the national banner slipped out of Marcin's hand and fell to the ground, but it was quickly picked up and saved from destruction by the Polish army's most valiant knights, which further motivated the Poles to strive for victory over the Teutonic Knights.

With the establishment of a dynastic union with the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in 1386, it became customary to use two banners—Polish and Lithuanian—as equally important insignia of royal authority. In the mid-16th century, before the creation of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (real union) in 1569, a single banner for the entire entity also came into use. The Commonwealth banner was initially plain white emblazoned with the arms of the Commonwealth which combined the heraldic charges of Poland (White Eagle) and Lithuania (Pursuer). During the 17th century, the banner was often divided into three or four horizontal stripes of white and red, ending with swallowtails. Elective kings' dynastic arms were often placed in an inescutcheon. Variants with the White Eagle and the Pursuer placed side by side without an escutcheon directly in the field or with the Eagle on the obverse and the Pogonia on the reverse side of the banner were also used.

During royal coronations, however, separate banners for each of the two constituent nations of the Commonwealth were still used. Crown (i.e., Polish) and Lithuanian standard-bearers carried the furled banners in a procession to the royal cathedral where, shortly after the anointment and just before the crowning of the king-elect, they handed the banners to the primate who unfurled them and handed them to the kneeling king. The king would then stand up and give the unfurled banners back to the standard-bearers.

Time of partitions

Partitions of Poland at the end of the 18th century brought an end to the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and Polish sovereignty. Nevertheless, succeeding puppet states often featured the Polish White Eagle or the colours white and red in their respective banners, notably the French Duchy of Warsaw and the German Grand Duchy of Posen. In 1815, the Congress of Vienna established a semi-autonomous Kingdom of Poland (known as the Congress Kingdom) under control of and in personal union with the Russian Empire. The Russian Tsars, who usurped the title of Polish kings, used a white royal banner emblazoned with the arms of the Congress Kingdom—a black double-headed Russian eagle with the White Eagle in an inescutcheon.

Interbellum

In August 1919, the Sejm (lower house of parliament) of the renascent Republic of Poland adopted a law defining the Banner of the Republic of Poland (chorągiew Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej). The banner was part of the insignia of the head of state—the State Leader (Naczelnik Państwa) and, later, President of the Republic. It was plain red emblazoned with the crowned White Eagle and bordered with a wężyk generalski, a wavy line used in the Polish military as a symbol of general's rank. It was modified on December 27, 1927, to reflect the adoption of a new official rendering of the national coat of arms.

As a symbol of presidential authority, the banner was carried or flown to mark the presence of the head of state and, at the same time, the commander-in-chief. It was flown on the president's official residence, and used as a car flag and instead of number plates on the president's vehicle. The banner was also used on special national occasions including the welcome ceremony for Ignacy Paderewski in Poznań in 1918 and Poland's wedding to the Baltic Sea in Puck in 1920. It also draped the coffins of Henryk Sienkiewicz in 1924, the Unknown Soldier in 1925, and Marshal Józef Piłsudski in 1935.

Second World War and People's Poland

Following the German-Soviet invasion of Poland in September 1939, President Ignacy Mościcki fled to Romania, taking the presidential insignia, including two specimens of the Banner of the Republic, with him. The banners were kept by the Polish government-in-exile in London until after the fall of Communism in Poland in 1989.

Meanwhile, the new Communist authorities at home used a modified version of the banner with a crownless White Eagle and a wider border. It was first used during the celebrations of the anniversary of the battle of Grunwald in 1945. Officially abandoned in 1955, the banner continued to be used in practice by the prime minister and, during the 1960s, by the Council of State, a collective head of state of the time.

Third Republic

On December 22, 1990, the last Polish president-in-exile, Ryszard Kaczorowski, handed the presidential insignia, including one of the banners rescued by Mościcki in 1939, to Lech Wałęsa, the first democratically elected president of post-war Poland. The ceremony, held at the Royal Castle in Warsaw was seen as a symbol of the Third Republic's continuity with the pre-war Second Republic. However, since legal regulations on national symbols did not recognize a national banner at that time, the banner brought by Kaczorowski did not become the presidential insignia again but was instead donated to the Royal Castle museum where it is now on display. The other of the two banners remains in the Sikorski Institute in London. Today, a kilim embroidered with the design of the pre-war Banner of the Republic is hanging in the Senate chamber, above the chair reserved for the President of Poland.

In 1996, the Minister of National Defense established a jack of the President of the Republic of Poland with the purpose of flying it on Polish Navy ships while the commander-in-chief is on board. The jack is identical in its design to the former Banner of the Republic of Poland. In 2005, the use of the presidential jack was extended to all branches of the Polish Armed Forces. It was first flown on land during a Constitution Day ceremony at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Warsaw on May 3, 2005.

Gallery

-

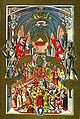

Crown and Lithuanian Standard-Bearers holding banners of Poland and Lithuania respectively in Erazm Ciołek's Pontifical (ca. 1515)

-

King Sigismund II Augustus' banner, 16th century

-

King Sigismund III's main banner, taken by the Swedish army in 1605

-

King Sigismund III's main banner, taken by the Swedish army in 1655

-

A presidential jack flying at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Warsaw during a Constitution Day ceremony

See also

References

- ^ Znamierowski, Alfred (1995). Stworzony do chwały (in Polish). Warsaw: Editions Spotkania. p. 299. ISBN 83-7115-055-5.

- ^ Pietras, Tomasz. "Od słowiańskich stanic do orzełka wojskowego. Z dziejów polskiej symboliki wojskowej" (PDF) (in Polish). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-02-06. Retrieved 2007-10-20.

- ^ Lileyko, Jerzy (1987). Regalia polskie (in Polish). Warsaw: Krajowa Agencja Wydawnicza. p. 153. ISBN 83-03-02021-8.

- ^ Długosz, Jan; transl. J. Mruk; edit. H. Samsonowicz (1984). Polska Jana Długosza. Wybór z pism (in Polish). Warsaw. Archived from the original on 2009-05-29. Retrieved 2007-08-01.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Mycielska, Dorota (January 2006) [September 1997]. "Sala obrad Senatu" (PDF). Senat Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej (in Polish). Kancelaria Senatu RP. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-02-16. Retrieved 2007-10-28.

- ^ (in Polish) Zarządzenie Ministra Obrony Narodowej z dnia 29 stycznia 1996 r. w sprawie szczegółowych zasad używania znaków Sił Zbrojnych Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej oraz ustalenia innych znaków używanych w Siłach Zbrojnych Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej (M.P.96.14.178 Archived 2007-09-30 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ (in Polish) Zarządzenie Ministra Obrony Narodowej z dnia 14 grudnia 2005 r. zmieniające zarządzenie w sprawie szczegółowych zasad używania znaków Sił Zbrojnych Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej oraz ustalenia innych znaków używanych w Siłach Zbrojnych Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej (M.P.05.82.1165 Archived 2007-09-30 at the Wayback Machine)

External links

- Kromer, Adam. "Polskie flagi i chorągwie". Chorągiew Królestwa Polskiego (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2007-08-05. Retrieved 2007-08-02.