Cardamom Range

The silhouette of the Cardamom Mountains appears in the provincial seal of Trat Province in Thailand.

Location and description

The mountain range extends along a southeast-northwest axis from Chanthaburi Province in Thailand, and Koh Kong Province in Cambodia on the Gulf of Thailand, to the Veal Veang District in Pursat Province, and extends to the southeast by the Dâmrei (Elephant) Mountains. The Thai part of the range comprise heavily eroded and dispersed mountain fragments of which the Khao Sa Bap, Khao Soi Dao and Chamao-Wong Mountains, east, north and west of Chanthaburi respectively, are the most prominent.

Dense tropical rainforest prevails on the wet westward slopes which annually receive from 3,800 to 5,000 mm (150 to 200 in) of rainfall. By contrast, only 1,000 to 1,500 mm (40 to 60 inches) fall on the wooded eastern slopes in the rain shadow facing the interior Cambodian plain, such as the Kirirom National Park. Most of the mountains are a dense wilderness, with almost no human population or activity, but on the eastern slopes, cardamom and pepper are grown commercially, and several large-scale construction projects have begun since the turn of the century.

Summits

The highest elevation of the Cardamom Mountains is Phnom Aural in the northeast at 1,813 m (5,948 ft). This is also Cambodia's highest peak.

Other important summits in the Cambodian parts are:

- Phnom Samkos (1,717 m (5,633 ft)

- Phnom Tumpor 1,516 m (4,974 ft)

- Phnom Kmoch 1,220 m (4,003 ft)

In Thailand, the most prominent peaks are:

- Khao Sa Bap 673 m (2,208 ft)

- Khao Soi Dao Tai 1,675 m (5,495 ft)

- Khao Chamao 1,024 m (3,360 ft)

History

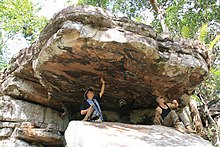

The Cardamom Mountains holds many historic sites and relics from the 15th- to 17th-century specifically. This includes a number of exposed burial sites of a type known as jar burials. The burials are scattered around the mountains, set out on remote, natural rock ledges, and contains 60 cm exotic ceramic jars and rough-hewn log coffins.

The jar burials are a unique feature of this region, and form a previously unrecorded burial practice in Khmer cultural history. Local legends suggest the bones are the remains of Cambodian royalty. Along with these jar burials archeologists have discovered various material evidence associated with the remains, such as glass beads consisting of various colors and composition. These glass beads, which were a common product in maritime trade between nearby countries, were most likely obtained by Cardamom Mountain communities by trading forest products, such as wood and resin, that they had access to.

Chulasirachumbot Cetiya in Namtok Phlio National Park, Thailand.

A unique rock art cave site known as Kanam depicts ancient elephants, elephant riders, deer and wild cow (or buffalo) in red ochre paint. The site is located in the eastern part of the Cardamoms near Kravanh Township (Pursat Province). The Cardamoms are home to one of the largest protected wild elephant populations in Southeast Asia. The human riders may represent elephant capture and training activities - a major cultural tradition among various ethnic groups in the area until the 1970s. Traditions, experts, and elephant populations were decimated by the Khmer Rouge Regime.

The cave and paintings may have played important roles for rituals and magic used to placate ancestors and spirits; seek protection (elephant capture is very dangerous); bring good fortune; and transmit specialized knowledge (teaching/training).

Some of the paintings may be various species of wild cow or buffalo. It is difficult to distinguish the possible cow from the possible deer representations due to the simple silhouette style. However, cowhides are extremely important for lassoes, ropes, snares and riggings related to elephant capture. Local elephant masters claimed there was more ritual and magic associated with these highly critical items than all others related to elephant capture. Thus, wild cow or buffalo representation might be expected.

The large representation of deer may relate to the massive deerskin trade to Japan in the 15th - 17th centuries. Taiwan's deer populations had been almost annihilated due to insatiable demands for Samurai armor and Japanese accessories made of deerskin. Deerskin sourcing shifted to Cambodia and Thailand. As deer populations decreased, local hunters also may have resorted to more investment in magic and ritual to seek assistance from ancestors and spirits to increase luck. The paintings are thought to date from the late Angkorian period through the post-Angkor period (contemporaneous with the jar burials, perhaps created and used by the same ethnic groups). The site may date to as early as the Funan period (1st - 6th centuries) when the practice of capturing, training, and trading live elephants was first historically noted (a mission was sent to China in 357 AD with trained elephants as part of the tributary gifts to Emperor Mu of Jin). Whether or not elephant capture, training, and use for labor, prestige and warfare existed prior to the Funan period is unknown. It is possible that the practice, technology and knowledge was obtained through South Asian influence in the early first millennium AD.

These paintings help with understanding the ecological history. Local ethnic groups were able to maintain, sustain and promote elephant populations through a somewhat symbiotic relation until the 20th century. Deer and wild cow/buffalo, however, may have been hunted to near extinction by the 15th - 17th centuries. Eld's deer, muntjac, sambar, gaur, kouprey and banteng were probably far more prevalent in the past.

Indigenous people

Part of the mountains are home to indigenous people, including the Chhong in both Thailand and Cambodia, and the ethnic Por (or Pear) in Pursat Province, Cambodia. They all belong to the group known as Pearic peoples. In Cambodia, indigenous people are collectively referred to as Khmer Loeu.

Khmer Rouge

This largely inaccessible mountain range formed one of the last strongholds of the Khmer Rouge, driven out by Vietnamese forces during the Cambodian–Vietnamese War. The Thai border to the west acted as a conduit for Chinese support and, eventually, a sanctuary for fleeing Khmer fighters and refugees.

Modern development

The inaccessibility of the hills has also helped to preserve the primeval forest and ecosystems of the area relatively intact. In 2002, however, a transborder highway to Thailand was completed south of the Cardamoms, along the coast. The highway has fragmented habitats for large mammals, such as elephants, big cats and monkeys. The highway has also opened up for agricultural slash-and-burn projects and opportunistic poaching for endangered animals, all degrading the natural value and the forests’ ecosystems.

Tourism is relatively new to the Cardamom Mountains. In 2008, Wildlife Alliance launched a community-based ecotourism program in the village of Chi-Phat, marketed as the "gateway to the Cardamoms". Tourist visitors to Chi-Phat continue to grow and the community is regarded as a model for community-based ecotourism, with approximately 3,000 annual visitors generating more than $US 150,000 for the local community.

International conservation organizations working in the area includes Wildlife Alliance, Conservation International, and Fauna and Flora International. In 2016, the southern slopes of the Cardamom Mountains were designated as a new national park; Southern Cardamom National Park. It appears, however, that rampant illegal poaching is continuing nonetheless.

Ecology

These relatively isolated mountains are part of the Cardamom Mountains rain forests ecoregion, an important ecoregion of mostly tropical moist broadleaf forest. Being one of the largest and still mostly unexplored forests in Southeast Asia, it is separated from other rainforests in the region by the large Khorat Plateau to the north. For these reasons, the ecoregion is home to several endemic species and is a refuge for species that have been decimated or are endangered elsewhere. The Vietnamese Phú Quốc island off the coast of Cambodia has similar vegetation and is included in the ecoregion.

Most of the ecoregion is covered in evergreen rain forest, but with several different habitats. Above 700 metres, a special thick evergreen forest-type dominates, and on the southern slopes of the Elephant Mountains, dwarf conifer Dacrydium elatum forests grow. On the Kirirom plateau, Tenasserim pine forest is found. The northern part of the Cardamom Mountains is home to the southernmost natural habitats of Betula (species Betula alnoides). Throughout, Hopea pierrei, an endangered canopy tree rare elsewhere, is relatively abundant in the Cardamom Mountains. Other angiosperm tree species are Anisoptera costata, Anisoptera glabra, Dipterocarpus costatus, Hopea odorata, Shorea hypochra, Caryota urens and Oncosperma tigillarium. Other conifers include Pinus kesiya, Dacrycarpus imbricatus, Podocarpus neriifolius, P. pilgeri and Nageia wallichiana.

Fauna

The moist climate and undisturbed nature of the rocky mountainsides appear to have allowed a rich variety of wildlife to thrive, although the Cardamom and Elephant Mountains are poorly researched and the wildlife that is assumed to be here remains to be catalogued. They are thought to be home to over 100 mammals, such as the large Indian civet and banteng cattle, and most importantly the mountains are thought to shelter at least 62 globally threatened animal species and 17 globally threatened trees, many of them endemic to Cambodia. Among the animals are fourteen endangered and threatened mammal species, including the largest population of Asian elephant in Cambodia and possibly the whole of Indochina although this still needs to be proved. Other mammals, many of which are threatened, include Indochinese tiger, clouded leopard (Pardofelis nebulosa), dhole (a wild dog) (Cuon alpinus), gaur (Bos gaurus), banteng (Bos javanicus), the disputed kting voar (Pseudonovibos spiralis), Malayan sun bear, pileated gibbon (Hylobates pileatus), Sumatran serow (Capricornis sumatraensis), Sunda pangolin and the Tenasserim white-bellied rat. There are at least 34 species of amphibians, three of them described as new species to science from here.

The rivers are home to both Irrawaddy and humpback dolphins and are home to some of the last populations on Earth of the very rare Siamese crocodiles and the only nearly extinct northern river terrapin, or royal turtle remaining in Cambodia. While the forests are habitat for more than 450 bird species, half of Cambodia's total of which four, the chestnut-headed partridge, Lewis's silver pheasant (Lophura nycthemera lewisi), the green peafowl (Pavo muticus) and the Siamese partridge (Arborophila diversa) are endemic to these mountains. A reptile and amphibian survey led in June 2007 by Dr Lee Grismer of La Sierra University in Riverside, California, USA, and the conservation organisation Fauna and Flora International uncovered new species, such as a new Cnemaspis gecko, C. neangthyi.

-

Malayan Sun Bear was formerly much more extant in South-East Asia

-

Lewis's silver pheasant

-

The vulnerable Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin is here

-

Lizards. Flower's long-headed lizard (pseudocalotes floweri), a species endemic to this region

-

Snakes. Here Vogel's pit viper (trimeresurus vogeli)

-

The moist conditions of the rain forests support numerous species of amphibians. (polypedates megacephalus, spot-legged tree frog)

Protected areas

With the establishment of the Southern Cardamom National Park in May 2016, nearly all of the Cardamom Mountains are now under some form of high level protection, mostly national park area and wildlife sanctuaries. However, the level of active protection has been criticised.

The human population of the Cardamom Mountain Range, although very small, is extremely poor. Threats to the ecological stability and biological diversity of the region include illegal wildlife poaching, habitat destruction due to illegal logging, construction and infrastructure projects, plantation clearings, mining projects, and forest fires caused by slash-and-burn agriculture. While the Cambodian forests in the Cardamom Mountains are fairly intact, the section in Thailand has been badly affected.

Protections in the Cardamom Mountains comprise the following:

- Cambodia

- Central Cardamom Mountains National Park

- Southern Cardamom National Park

- Botum-Sakor National Park

- Kirirom National Park

- Preah Monivong National Park (aka Bokor National Park)

- Phnom Samkos Wildlife Sanctuary

- Phnom Aural Wildlife Sanctuary

- Tatai Wildlife Sanctuary

- Peam Krasop Wildlife Sanctuary

- Thailand

- Namtok Khlong Kaeo National Park

- Namtok Phlio National Park

- Khao Khitchakut National Park

- Khao Chamao-Khao Wong National Park

- Khao Soi Dao Wildlife Sanctuary

- Klong Kruewai Chalerm Prakiat Wildlife Sanctuary

- Khao Ang Rue Nai Wildlife Sanctuary.

Threats

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2019) |

The flora, fauna and ecosystems of the Cardamom Mountains are threatened by large construction and infrastructure projects, mining, illegal logging, and opportunistic hunting and poaching.

Despite the very high level of protectional status, the actual protection of the conservation areas and implementation of the law has been very poor. The violation of the protection laws has happened on all levels, from opportunistic locals, and local business entrepreneurs, to governmental institutions, foreign companies and international criminal organisations. In the late 2010s, international conservation organisations, and the UN, has collaborated with the Cambodian government to halt a number of planned construction projects and clearings in protected areas. In 2016, the Cambodian government established a collaboration with international conservation organisations to increase on-ground patrolling and actual park ranger services, building several ranger headquarters and hiring armed personnel with arresting rights. This might signify a change in the destructive trends, at least concerning governmental responsibilities.

Tourism

The Cardamom Mountains are an emerging tourist destination.

The village of Chi Phat runs a Community-Based Eco-Tourism project with the support of conservation NGO, Wildlife Alliance. Previously a logging and hunting community, villagers now make sustainable income through homestays, multiple day guided treks to natural and cultural sites, mountain bike, boat and bird watching tours.

The Wildlife Release Station in Koh Kong Province is a release site for animals rescued from the illegal wildlife trade in Cambodia by the NGO Wildlife Alliance. Binturong, porcupine, pangolins, civets, macaques and an array of birds are among the many species that have been released on site. The station was opened to tourists in December 2013, offering guests an insight into the workings of a wildlife rehabilitation and release site while staying in jungle chalets and enjoying Cambodian hospitality. Activities offered can include feeding resident wildlife, jungle hiking, radio tracking and setting camera traps to monitor released wildlife.

Wild Animal Rescue (WAR Adventures Cambodia) also organize a wide range of deep jungle activities from the family trekking to the hardcore RAID adventure, jungle orientation and survival training course, even animals and human tracking course, all in the region of Sre Ambel in the South-west of the Cardamom mountains.

-

Scenic nature

-

Campsite in Khao Khitchakut National Park, Thailand

-

Campsite in Kirirom National Park, Cambodia

-

The waterfalls in the Thai part of the mountains are popular destinations

See also

- Dâmrei Mountains

- Cardamom Khmer, a variant of the Khmer language spoken in these mountains

- K5 Plan

References

- ^ "Cambodia Ecological Zonation" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2012-01-28.

- ^ Seals of The Provinces of Thailand

- ^ Cardamom and Elephant Mountains (Cambodia) It does snow in these mountain rangesArchived 2012-03-25 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Beavan, Nancy; Halcrow, Sian; McFaden, Bruce; Hamilton, Derek; Buckley, Brendan; Tep, Sokha; Shewan, Louise; Ouk, Sokha; Fallon, Stewart (2012). "Radiocarbon Dates from Jar and Coffin Burials of the Cardamom Mountains Reveal a Unique Mortuary Ritual in Cambodia's Late- to Post-Angkor Period (15th–17th Centuries AD)". Radiocarbon. 54 (1): 1–22. Bibcode:2012Radcb..54....1B. doi:10.2458/azu_js_rc.v54i1.15828. hdl:1885/52455. ISSN 1945-5755.

- ^ Beavan, Nancy; Hamilton, Derek; Tep, Sokha; Sayle, Kerry (2015). "Radiocarbon Dates from the Highland Jar and Coffin Burial Site of Phnom Khnang Peung, Cardamom Mountains, Cambodia" (PDF). Radiocarbon. 57 (1): 15–31. Bibcode:2015Radcb..57...15B. doi:10.2458/azu_rc.57.18194. ISSN 1945-5755. S2CID 129583294.

- ^ "ANU - Ceramic Jars". Archived from the original on 2012-03-17. Retrieved 2011-11-14.

- ^ Carter, A. K.; Dussubieux, L.; Beavan, N. (2016). "Glass Beads from 15th–17th Century CE Jar Burial Sites in Cambodia's Cardamom Mountains". Archaeometry. 58 (3): 401–412. doi:10.1111/arcm.12183. ISSN 1475-4754.

- ^ Latinis, D. Kyle; Griffin, P. Bion; Tep, Sokha (May 2016). "The Kanam Rock Painting Site, Cambodia: Current Assessments". NSC Archaeological Report Series. #2: 1–91.

- ^ Beyond material benefits – Connecting conservation and cultural identity in Cambodia

- ^ "The Survival of Cambodia's Ethnic Minorities". www.culturalsurvival.org. Archived from the original on 2019-06-08. Retrieved 2019-12-09.

- ^ Fiona Terry (12 April 2013). Condemned to Repeat?: The Paradox of Humanitarian Action. Cornell University Press. pp. 118–. ISBN 978-0-8014-6863-6.

- ^ "Southern Cardamom Forest Registered as a National Park!". Wildlife Alliance. 18 May 2016. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 14 August 2018.

- ^ Lonely Planet Chi Phat

- ^ Reimer, J. K., & Walter, P. (2013). How do you know it when you see it? Community-based ecotourism in the Cardamom Mountains of southwestern Cambodia. Tourism Management, 34, 122-132.

- ^ "Wildlife Alliance Forest Protection Program". Archived from the original on 2013-11-12. Retrieved 2013-11-25.

- ^ Conservation International Cambodia Program

- ^ Fauna & Flora International Cardamoms Mountain Program

- ^ "Over 100,000 snares found in Cardamom National Park". The Phnom Penh Post. 25 May 2018. Retrieved 14 August 2018.

- ^ "Cardamom Mountains rain forests". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund.

- ^ "World Wildlife Fund - Cardamom Mountains Moist Forests". Archived from the original on 2015-05-17. Retrieved 2012-02-21.

- ^ "Conifers of Cambodia, Lao PDR and Vietnam". Science/Genetics & Conservation/Conifer Conservation. Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh. 2010. Archived from the original on 29 November 2007. Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- ^ Forest Vegetation of Cardamom Mountains, Cambodia. A.N. Kuznetsov, S.P. Kuznetsova. BULLETIN OF MOSCOW SOCIETY OF NATURALISTS. BIOLOGICAL SERIES. 2012. Vol. 117, part 5, 2012 September – October, p. 39–50 (in Russian)

- ^ BBC News, "New cryptic gecko species is discovered in Cambodia ", 24 March 2010: accessed 24 March 2010.

- ^ CeroPath - Niviventer tenaster Thomas, 1916

- ^ Ohler, A.; S. R. Swan; J. C. Daltry (2002). "A recent survey of the amphibian fauna of the Cardamom Mountains, Southwest Cambodia with descriptions of three new species" (PDF). Raffles Bulletin of Zoology. 50: 465–481.

- ^ Grismer, J. L.; Grismer, L. L.; Chav, T. (2010). "New Species of Cnemaspis Strauch 1887 (Squamata: Gekkonidae) from Southwestern Cambodia". Journal of Herpetology. 44: 28–36. doi:10.1670/08-211.1. S2CID 86089147.

- ^ Mech Dara (25 May 2018). "Over 100,000 snares found in Cardamom National Park". The Phnom Penh Post. Retrieved 14 December 2019.

- ^ Timothy J. Killeen (2012). The Cardamom Conundrum - Reconciling Development and Conservation in the Kingdom of Cambodia. NUS Press. ISBN 978-9971-69-614-6.

- ^ Cardamom National Park, Cambodia

- ^ Duncan Forgan (25 June 2018). "How Luxury Camps are Saving the Cardamom Mountains". Remote Lands. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

External links

- Cardamom Mountains Moist Forests (WWF website)

- Description by Wayne McCallum of a trip through the forests in 2005

- Gerald Flynn; Vutha Srey (27 June 2024). "History repeats as logging linked to Cambodian hydropower dam in Cardamoms". Mongabay.