Chauvet Cave

Discovered on December 18, 1994, it is considered one of the most significant prehistoric art sites and the UN's cultural agency UNESCO granted it World Heritage status on June 22, 2014. The cave was first explored by a group of three speleologists: Eliette Brunel-Deschamps, Christian Hillaire, and Jean-Marie Chauvet (for whom the cave was named) six months after an aperture now known as "Le Trou de Baba" ('Baba's Hole') was discovered by Michel Rosa (Baba). At a later date the group returned to the cave. Another member of this group, Michel Chabaud, along with two others, travelled further into the cave and discovered the Gallery of the Lions, the End Chamber. Chauvet has his own detailed account of the discovery. In addition to the paintings and other human evidence, they also discovered fossilized remains, prints, and markings from a variety of animals, some of which are now extinct.

Further study by French archaeologist Jean Clottes has revealed much about the site. The dates have been a matter of dispute but a study published in 2012 supports placing the art in the Aurignacian period, approximately 32,000–30,000 years ago. A study published in 2016 using an additional 88 radiocarbon dates showed two periods of habitation, one 37,000 to 33,500 years ago and the second from 31,000 to 28,000 years ago, with most of the black drawings dating to the earlier period.

Features

The cave is situated above the previous course of the Ardèche before the Pont d'Arc opened up. The gorges of the Ardèche region are the site of numerous caves, many of them having some geological or archaeological importance.

Based on radiocarbon dating, the cave appears to have been used by humans during two distinct periods: the Aurignacian and the Gravettian. Most of the artwork dates to the earlier, Aurignacian, era (32,000 to 30,000 years ago). The later Gravettian occupation, which occurred 27,000 to 25,000 years ago, left little but a child's footprints, the charred remains of ancient hearths, and carbon smoke stains from torches that lit the caves. The footprints may be the oldest human footprints that can be accurately dated. After the child's visit to the cave, evidence suggests that due to a landslide that covered its historical entrance, the cave remained untouched until it was discovered in 1994.

The soft, clay-like floor of the cave retains the paw prints of cave bears along with large, rounded depressions that are believed to be the "nests" where the bears slept. Fossilised bones are abundant and include the skulls of cave bears and the horned skull of an ibex. Paw-prints dated to 26,000 YBP are suggested as being those of a dog; however, these have been challenged as being left by a wolf.

Paintings

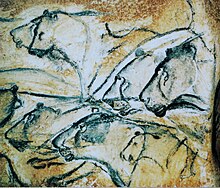

Hundreds of animal paintings have been catalogued, depicting at least 13 different species, including some rarely or never found in other ice age paintings. Rather than depicting only the familiar herbivores that predominate in Paleolithic cave art, i.e. horses, aurochs, mammoths, etc., the walls of the Chauvet Cave feature many predatory animals, e.g., cave lions, leopards, bears, and cave hyenas. There are also paintings of rhinoceroses.

Typical of most cave art, there are no paintings of complete human figures, although there are two partial "Venus" figures: one within a niche or vestibule of the End Chamber, and the other on a roughly conical or dental-shaped pendant several meters away; both are composed of what appears to be a vulva attached to an incomplete pair of legs. Above the pendant Venus, and in contact with it, is a bison head, which has led some to describe the composite drawing as a Minotaur. There are a few panels of red ochre hand prints and hand stencils made by blowing pigment over hands pressed against the cave surface. Abstract markings—lines and dots—are found throughout the cave. There are also two unidentifiable images that have a vaguely butterfly or avian shape to them. This combination of subjects has led some students of prehistoric art and cultures to believe that there was a ritual, shamanic, or magical aspect to these paintings.

One drawing, later overlaid with a sketch of a deer, is reminiscent of a volcano spewing lava, similar to the regional volcanoes that were active at the time. If confirmed, this would represent the earliest known drawing of a volcanic eruption.

The artists who produced these paintings used techniques rarely found in other cave art. Many of the paintings appear to have been made only after the walls were scraped clear of debris and concretions, leaving a smoother and noticeably lighter area upon which the artists worked. Similarly, a three-dimensional quality and the suggestion of movement are achieved by incising or etching around the outlines of certain figures. The art is also exceptional for its time for including "scenes", e.g., animals interacting with each other; a pair of woolly rhinoceroses, for example, are seen butting horns in an apparent contest for territory or mating rights.

Dating

The cave contains some of the oldest known cave paintings, based on radiocarbon dating of "black from drawings, from torch marks and from the floors", according to Jean Clottes. Clottes concludes that the "dates fall into two groups, one centred around 27,000–26,000 BP and the other around 32,000–30,000 BP." As of 1999, the dates of 31 samples from the cave had been reported. The earliest, sample Gifa 99776 from "zone 10", dates to 32,900 ± 490 BP.

Some archaeologists have questioned these dates. Christian Züchner, relying on stylistic comparisons with similar paintings at other well-dated sites, expressed the opinion that the red paintings are from the Gravettian period (c. 28,000–23,000 BP) and the black paintings are from the Early Magdalenian period (early part of c. 18,000–10,000 BP). Pettitt and Bahn also contended that the dating is inconsistent with the traditional stylistic sequence and that there is uncertainty about the source of the charcoal used in the drawings and the extent of surface contamination on the exposed rock surfaces. Stylistic studies showed that some Gravettian engravings are superimposed on black paintings proving the paintings' older origins.

By 2011, more than 80 radiocarbon dates had been taken, with samples from torch marks and from the paintings themselves, as well as from animal bones and charcoal found on the cave floor. The radiocarbon dates from these samples suggest that there were two periods of creation in Chauvet: 35,000 years ago and 30,000 years ago. This would place the occupation and painting of the cave within the Aurignacian period.

A research article published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in May 2012 by scientists from the University of Savoy, Aix-Marseille University and the Centre National de Prehistoire confirmed that the paintings were created by people in the Aurignacian era, between 30,000 and 32,000 years ago. The researchers' findings are based on the analysis using geomorphological and

Cl dating of the rock slide surfaces around what is believed to be the cave's only entrance. Their analysis showed that the entrance was sealed by a collapsing cliff some 29,000 years ago. Their findings put the date of human presence in the cave and the paintings in line with that deduced from radiocarbon dating, i.e., between 32,000–30,000 years BP.

A 2016 study in the same journal examining 259 radiocarbon dates, some unpublished before, concluded that there were two phases of human occupation, one running from 37,000 to 33,500 years ago and the second from 31,000 to 28,000 years ago. All but two of the dates for the black drawings were from the earlier phase. The authors believe that the first phase ended with a rockfall that sealed the cave, with two more rockfalls at the end of the second occupation phase after which no humans or large animals entered the cave until it was rediscovered. In an email to the Los Angeles Times two of the authors explained,

A human group (band or tribe) visited the Chauvet cave during the first period around 36,000 years ago for cultural purposes. They produced black drawings of huge mammals. Then, several thousands of years after, another group from another place with another culture visited the cave.

In 2020, researchers used the new IntCal20 radiocarbon calibration curve to estimate that the oldest painting in the cave was created 36,500 years ago.

In parallel with the dating carried out in Chauvet cave itself, from 2008 onwards, several members of the scientific team in charge of studying the cave undertook chronological research in other rock art sites along the Ardèche river gorges under the direction of Julien Monney. It took place at Points cave (Aiguèze; Gard; France), which presents flagrant iconographic similarities with Chauvet cave, but also at Deux-Ouvertures cave. Under the name of "Datation Grottes Ornées" (or DGO) project, this research is intended to determine the context in which the rock art caves of the region were visited. The DGO project proposes to discuss the apparent chronological and iconographic exceptionality of Chauvet cave "from the outside" by placing it within a regional ensemble. This research is still in progress (2020). However, it has already produced many results indirectly concerning the chronology of Chauvet cave.

Preservation

The cave has been sealed off to the public since 1994. Access is severely restricted owing to the experience with decorated caves such as Altamira and Lascaux found in the 19th and 20th century, where the admission of visitors on a large scale led to the growth of mold on the walls that damaged the art in places. In 2000 the archaeologist and expert on cave paintings Dominique Baffier was appointed to oversee conservation and management of the cave. She was followed in 2014 by Marie Bardisa.

Caverne du Pont-d'Arc (Grotte Chauvet 2), a facsimile of Chauvet Cave on the model of the so-called "Faux Lascaux", was opened to the general public on 25 April 2015. It is the largest cave replica ever built worldwide, ten times bigger than the Lascaux facsimile. The art is reproduced full-size in a condensed replica of the underground environment, in a circular building above ground, a few kilometres from the actual cave. Visitors' senses are stimulated by the same sensations of silence, darkness, temperature, humidity, and acoustics, carefully reproduced.

See also

- Art of the Upper Paleolithic

- Cave of Forgotten Dreams, a 2010 documentary film about Chauvet Cave by Werner Herzog

- Coliboaia Cave in Romania, where 35–32,000-year-old figures were drawn using a similar technique

- List of Stone Age art

References

- ^ UNESCO. [1], June 2014.

- ^ Clottes (2003b), p. 214.

- ^ France 24. "UNESCO grants heritage status to prehistoric French cave" Archived 2018-01-07 at the Wayback Machine, June 2014.

- ^ Hammer, Joshua (April 2015). "Finally, the Beauty of France's Chauvet Cave Makes its Grand Public Debut". Smithsonian. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- ^ Chauvet, Jean-Marie; Deschamps, Eliette Brunel; Hillaire, Christian; Clottes, Jean; Bahn, Paul (1996). Dawn of art : the Chauvet Cave : the oldest known paintings in the world. New York: H.N. Abrams. ISBN 0-8109-3232-6.

- ^ Ferrier, Catherine; Debard, Évelyne; Kervazo, Bertrand; Brodard, Aurélie; Guibert, Pierre; Baffier, Dominique; Feruglio, Valérie; Gély, Bernard; Geneste, Jean-Michel; Maksud, Frédéric (2014-12-28). "Heated walls of the cave Chauvet-Pont d'Arc (Ardèche, France): characterization and chronology". PALEO. Revue d'archéologie préhistorique (25): 59–78. doi:10.4000/paleo.3009. ISSN 1145-3370. Retrieved 2019-10-25.

- ^ Curtis, Gregory (2006). The Cave Painters: Probing the Mysteries of the World's First Artists. New York: Knopf, pp. 215–16.

- ^ "Smithsonian Magazine, December 2010". Smithsonianmag.com. 2017-06-21. Archived from the original on 2013-11-02. Retrieved 2018-01-31.

- ^ Thalmann, O.; Shapiro, B.; Cui, P.; Schuenemann, V.J.; Sawyer, S.K.; Greenfield, D.L.; Germonpré, M.B.; Sablin, M.V.; López-Giráldez, F.; Domingo-Roura, X.; Napierala, H.; Uerpmann, H-P.; Loponte, D.M.; Acosta, A.A.; Giemsch, L.; Schmitz, R.W.; Worthington, B.; Buikstra, J.E.; Druzhkova, A.S.; Graphodatsky, A.S.; Ovodov, N.D.; Wahlberg, N.; Freedman, A.H.; Schweizer, R.M.; Koepfli, K.-P.; Leonard, J.A.; Meyer, M.; Krause, J.; Pääbo, S.; Green, R.E.; Wayne, Robert K. (15 November 2013). "Complete Mitochondrial Genomes of Ancient Canids Suggest a European Origin of Domestic Dogs". Science. 342 (6160): 871–874. Bibcode:2013Sci...342..871T. doi:10.1126/science.1243650. PMID 24233726. S2CID 1526260. refer Supplementary material Page 27 Table S1

- ^ Diedrich, Cajus G. (15 September 2013). "Late Pleistocene leopards across Europe – northernmost European German population, highest elevated records in the Swiss Alps, complete skeletons in the Bosnia Herzegowina Dinarids and comparison to the Ice Age cave art". Quaternary Science Reviews. 76: 167–193. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2013.05.009. ISSN 0277-3791. Retrieved 11 February 2024 – via Elsevier Science Direct.

- ^ Adams, Laurie (2011). Art Across Time (4th ed.). Mc-Graw Hill. p. 34.

- ^ Thurman, Judith (23 June 2008). "First Impressions: What does the world's oldest art say about us?". The New Yorker Magazine.

- ^ See, for example, Lewis-Williams (2002).

- ^ Callaway, Ewen (15 January 2016). "'Cave of forgotten dreams' may hold earliest painting of volcanic eruption". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2016.19177. S2CID 189976837.

- ^ Fritz, Carole; Tosello, Gilles (2007-02-21). "The Hidden Meaning of Forms: Methods of Recording Paleolithic Parietal Art". Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory. 14 (1). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 48–80. doi:10.1007/s10816-007-9027-3. ISSN 1072-5369. S2CID 144998541.

- ^ Clottes (2003b), p. 33. See also Chauvet (1996), p. 131, for a chronology of dates from various caves. Bahn's foreword and Clottes' epilogue to Chauvet (1996) discuss dating.

- ^ Züchner, Christian (September 1998). "Grotte Chauvet Archaeologically Dated". Communication at the International Rock Art Congress IRAC ´98. Retrieved 2014-12-05. Clottes (2003b), pp. 213–14, has a response by Clottes.

- ^ Pettitt, Paul; Paul Bahn (March 2003). "Current problems in dating Palaeolithic cave art: Candamo and Chauvet". Antiquity. 77 (295): 134–41. doi:10.1017/s0003598x00061421. S2CID 161903280.

- ^ Pettitt, P. (2008). "Art and the Middle-to-Upper Paleolithic transition in Europe: Comments on the archaeological arguments for an early Upper Paleolithic antiquity of the Grotte Chauvet art". Journal of Human Evolution, 2008 Aug 2. (abstract)

- ^ Bahn, P., P. Pettitt and C. Züchner, "The Chauvet Conundrum: Are claims for the 'birthplace of art' premature?" in An Enquiring Mind: Studies in Honor of Alexander Marshack (ed. P. Bahn), Oxford 2009, pp. 253–78.

- ^ Guy, Emmanuel (2004). The Grotte Chauvet: a completely homogeneous art? Archived 2014-07-30 at the Wayback Machine, paleoesthetique.com, February 2004.

- ^ "A Chauvet Primer". Archaeology. 64 (2): 39. March–April 2011.

- ^ Agence France-Presse (May 7, 2012). "France cave art gives glimpse into human life 40,000 years ago". National Post. Retrieved May 8, 2012.

- ^ Sadier, Benjamin; Delannoy, Jean-Jacques; Benedetti, Lucilla; Bourles, Didier; Jaillet, Stephane; Geneste, Jean-Michel; Lebatard, Anne-Elisabeth; Arnold, Maurice (2012). "Further constraints on the Chauvet cave artwork elaboration". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (21): 8002–6. Bibcode:2012PNAS..109.8002S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1118593109. PMC 3361430. PMID 22566649.

- ^ Anita Quiles, Hélène Valladas, Hervé Bocherens, Emmanuelle Delqué-Kolic, Evelyne Kaltnecker, Johannes van der Plicht, Jean-Jacques Delannoy, Valérie Feruglio, Carole Fritz, Julien Monney, Michel Philippe, Gilles Tosello, Jean Clottes, and Jean-Michel Geneste "A high-precision chronological model for the decorated Upper Paleolithic cave of Chauvet-Pont d'Arc, Ardèche, France" PNAS 2016 113 (17) 4670–75; doi:10.1073/pnas.1523158113 [2]

- ^ Netburn, Deborah (December 2016). "Chauvet cave: The most accurate timeline yet of who used the cave and when". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- ^ Turney, Chris; Hogg, Alan; Reimer, Paula J.; Heaton, Tim (13 August 2020). "From cave art to climate chaos: How a new carbon dating timeline is changing our view of history". Phys.org. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- ^ Monney, Julien (2018). "La grotte aux Points d'Aiguèze, petite soeur de la grotte Chauvet et les recherches menées dans le cadre du projet "Datation Grottes Ornées"". Karstologia. 72: 1–12. ISSN 0751-7688.

- ^ Monney, Julien (2018). "L'art pariétal paléolithique de la grotte aux Points d'Aiguèze : définition d'un dispositif pariétal singulier et discussion de ses implications". Karstologia. 72: 45–60. ISSN 0751-7688.

- ^ Monney, Julien (2010). "La grotte des Deux-Ouvertures : Le regard et la mémoire". Ardèche Archéologie. 27: 3–12.

- ^ Monney, Julien (2014). "Nouveaux éléments de discussion chronologique dans le paysage des grottes ornées de l'Ardèche: Oulen, Chabot et Tête-du-Lion". Paléo: 271–283. ISSN 1145-3370.

- ^ Monney, Julien (2014). "La grotte des Deux-Ouvertures à Saint-Martin-d'Ardèche: approches chronométriques croisées de la mise en place du massif stalagmitique (U/Th et 14C AMS): implications quant aux fréquentations humaines de la cavité et à la présence ursine dans la région". Paléo: 41–50. ISSN 1145-3370.

- ^ Condemi, Silvana; Voisin, Jean-Luc; Puymérail, Laurent; Monney, Julien; Philippe, Michel (2017-06-01). "Les restes humains de la grotte ornée paléolithique des Deux-Ouvertures (Ardèche, France)". Comptes Rendus Palevol. 16 (4): 452–461. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2017.02.001. ISSN 1631-0683.

- ^ Rauchhaupt, Ulf von. "Replik der Grotte Chauvet mit Höhlenmalereien". faz.net. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- ^ "Chauvet-Pont d'Arc cave, grand opening!". TRACCE Online Rock Art Bulletin. 7 February 2015. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- ^ "Conservation of prehistoric caves and stability of their inner climate: lessons from Chauvet and other French caves". Bourges F., Genthon P., Genty D., Lorblanchet M., Mauduit E., D'Hulst D. Science of the Total Environment. Vol. 493, 15 Sept. 2014, pp. 79–91 doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.05.137.

- ^ "Drawing Paleolithic Romania".

Bibliography

- Chauvet, Jean-Marie; Eliette Brunel Deschamps; Christian Hillaire (1996). Dawn of Art: The Chauvet Cave. Paul G. Bahn (Foreword), Jean Clottes (Epilogue). New York: Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 0-8109-3232-6. English translation by Paul G. Bahn from the French edition La Grotte Chauvet

- Clottes, Jean (2003a). Return To Chauvet Cave, Excavating the Birthplace of Art: The First Full Report. Thames & Hudson. p. 232. ISBN 0-500-51119-5.

- Clottes, Jean (2003b). Chauvet Cave: The Art of Earliest Times. Paul G. Bahn (translator). University of Utah Press. ISBN 0-87480-758-1. Translation of La Grotte Chauvet, l'art des origins, Éditions du Seuil, 2001.

- Lewis-Williams, David (2002). The Mind in the Cave. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28465-0.

- Clottes, Jean (August 2001). "France's Magical Ice Age Art". National Geographic. 200 (2). Archived from the original on February 3, 2008. (article includes many photographs)

External links

- The Cave of Chauvet-Pont-d'Arc French Ministry of Culture information site; includes an interactive map with photos.

- Ancient Grand Masters: Chauvet Cave, France A brief article by Jean Clottes of the French Ministry of Culture, responsible for overseeing the authentication of the contents and art of the cave

- Chauvet Cave (ca. 30,000 b.c.) on the Metropolitan Museum of Art's Timeline of Art History

- Cave of Forgotten Dreams a film by Werner Herzog using 3D technology