Civil War Era

Decades of controversy over slavery were brought to a head when Abraham Lincoln, who opposed slavery's expansion, won the 1860 presidential election. Seven Southern slave states responded to Lincoln's victory by seceding from the United States and forming the Confederacy. The Confederacy seized U.S. forts and other federal assets within their borders. The war began on April 12, 1861, when the Confederacy bombarded Fort Sumter in South Carolina. A wave of enthusiasm for war swept over the North and South, as military recruitment soared. Four more Southern states seceded after the war began and, led by its president, Jefferson Davis, the Confederacy asserted control over a third of the U.S. population in eleven states. Four years of intense combat, mostly in the South, ensued.

During 1861–1862 in the Western theater, the Union made permanent gains—though in the Eastern theater the conflict was inconclusive. The abolition of slavery became a Union war goal on January 1, 1863, when Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which declared all slaves in rebel states to be free, applying to more than 3.5 million of the 4 million enslaved people in the country. To the west, the Union first destroyed the Confederacy's river navy by the summer of 1862, then much of its western armies, and seized New Orleans. The successful 1863 Union siege of Vicksburg split the Confederacy in two at the Mississippi River, while Confederate General Robert E. Lee's incursion north failed at the Battle of Gettysburg. Western successes led to General Ulysses S. Grant's command of all Union armies in 1864. Inflicting an ever-tightening naval blockade of Confederate ports, the Union marshaled resources and manpower to attack the Confederacy from all directions. This led to the fall of Atlanta in 1864 to Union General William Tecumseh Sherman, followed by his March to the Sea. The last significant battles raged around the ten-month Siege of Petersburg, gateway to the Confederate capital of Richmond. The Confederates abandoned Richmond, and on April 9, 1865, Lee surrendered to Grant following the Battle of Appomattox Court House, setting in motion the end of the war. Lincoln lived to see this victory but was shot by an assassin on April 14, dying the next day.

By the end of the war, much of the South's infrastructure was destroyed. The Confederacy collapsed, slavery was abolished, and four million enslaved black people were freed. The war-torn nation then entered the Reconstruction era in an attempt to rebuild the country, bring the former Confederate states back into the United States, and grant civil rights to freed slaves. The war is one of the most extensively studied and written about episodes in the history of the United States. It remains the subject of cultural and historiographical debate. Of continuing interest is the myth of the Lost Cause of the Confederacy. The war was among the first to use industrial warfare. Railroads, the electrical telegraph, steamships, the ironclad warship, and mass-produced weapons were widely used. The war left an estimated 698,000 soldiers dead, along with an undetermined number of civilian casualties, making the Civil War the deadliest military conflict in American history. The technology and brutality of the Civil War foreshadowed the coming World Wars.

Origins

The origins of the war were rooted in the desire of the Southern states to preserve the institution of slavery. Historians in the 21st century overwhelmingly agree on the centrality of slavery in the conflict—at least for the Southern states. They disagree on which aspects (ideological, economic, political, or social) were most important, and on the North's reasons for refusing to allow the Southern states to secede. The pseudo-historical Lost Cause ideology denies that slavery was the principal cause of the secession, a view disproven by historical evidence, notably some of the seceding states' own secession documents. After leaving the Union, Mississippi issued a declaration stating, "Our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery—the greatest material interest of the world."

The principal political battle leading to Southern secession was over whether slavery would expand into the Western territories destined to become states. Initially Congress had admitted new states into the Union in pairs, one slave and one free. This had kept a sectional balance in the Senate but not in the House of Representatives, as free states outstripped slave states in numbers of eligible voters. Thus, at mid-19th century, the free-versus-slave status of the new territories was a critical issue, both for the North, where anti-slavery sentiment had grown, and for the South, where the fear of slavery's abolition had grown. Another factor leading to secession and the formation of the Confederacy was the development of white Southern nationalism in the preceding decades. The primary reason for the North to reject secession was to preserve the Union, a cause based on American nationalism.

Background factors in the run up to the Civil War were partisan politics, abolitionism, nullification versus secession, Southern and Northern nationalism, expansionism, economics, and modernization in the antebellum period. As a panel of historians emphasized in 2011, "while slavery and its various and multifaceted discontents were the primary cause of disunion, it was disunion itself that sparked the war."

Lincoln's election

Abraham Lincoln won the 1860 presidential election. Southern leaders feared Lincoln would stop slavery's expansion and put it on a course toward extinction. His victory triggered declarations of secession by seven slave states of the Deep South, all of whose riverfront or coastal economies were based on cotton that was cultivated by slave labor. Lincoln was not inaugurated until March 4, 1861, giving the South time to prepare for war during the winter of 1860–1861. Nationalists in the North and "Unionists" in the South refused to accept the declarations of secession. No foreign government ever recognized the Confederacy. The U.S. government, under President James Buchanan, refused to relinquish its forts that were in territory claimed by the Confederacy. According to Lincoln, the American people had shown they had been successful in establishing and administering a republic, but a third challenge faced the nation: maintaining a republic based on the people's vote, in the face of an attempt to destroy it.

Outbreak of the war

Secession crisis

Lincoln's election provoked South Carolina's legislature to call a state convention to consider secession. South Carolina had done more than any other state to advance the notion that a state had the right to nullify federal laws and even secede. On December 20, 1860, the convention unanimously voted to secede and adopted a secession declaration. It argued for states' rights for slave owners but complained about states' rights in the North in the form of resistance to the federal Fugitive Slave Act, claiming that Northern states were not fulfilling their obligations to assist in the return of fugitive slaves. The "cotton states" of Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas followed suit, seceding in January and February 1861.

Among the ordinances of secession, those of Texas, Alabama, and Virginia mentioned the plight of the "slaveholding states" at the hands of Northern abolitionists. The rest made no mention of slavery but were brief announcements by the legislatures of the dissolution of ties to the Union. However, at least four—South Carolina, Mississippi, Georgia, and Texas—provided detailed reasons for their secession, all blaming the movement to abolish slavery and its influence over the North. Southern states believed that the Fugitive Slave Clause made slaveholding a constitutional right. These states agreed to form a new federal government, the Confederate States of America, on February 4, 1861. They took control of federal forts and other properties within their boundaries, with little resistance from outgoing President James Buchanan, whose term ended on March 4. Buchanan said the Dred Scott decision was proof the Southern states had no reason to secede and that the Union "was intended to be perpetual". He added, however, that "The power by force of arms to compel a State to remain in the Union" was not among the "enumerated powers granted to Congress". A quarter of the US army—the Texas garrison—was surrendered in February to state forces by its general, David E. Twiggs, who joined the Confederacy.

As Southerners resigned their Senate and House seats, Republicans could pass projects that had been blocked. These included the Morrill Tariff, land grant colleges, a Homestead Act, a transcontinental railroad, the National Bank Act, authorization of United States Notes by the Legal Tender Act of 1862, and the end of slavery in the District of Columbia. The Revenue Act of 1861 introduced income tax to help finance the war.

In December 1860, the Crittenden Compromise was proposed to re-establish the Missouri Compromise line, by constitutionally banning slavery in territories to the north of it, while permitting it to the south. The Compromise would likely have prevented secession, but Lincoln and the Republicans rejected it. Lincoln stated that any compromise that would extend slavery would bring down the Union. A February peace conference met in Washington, proposing a solution similar the Compromise; it was rejected by Congress. The Republicans proposed the Corwin Amendment, an alternative, not to interfere with slavery where it existed, but the South regarded it as insufficient. The remaining eight slave states rejected pleas to join the Confederacy, following a no-vote in Virginia's First Secessionist Convention on April 4.

On March 4, Lincoln was sworn in as president. In his inaugural address, he argued that the Constitution was a more perfect union than the earlier Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union, was a binding contract, and called secession "legally void". He did not intend to invade Southern states, nor to end slavery where it existed, but he said he would use force to maintain possession of federal property, including forts, arsenals, mints, and customhouses that had been seized. The government would not try to recover post offices, and if resisted, mail delivery would end at state lines. Where conditions did not allow peaceful enforcement of federal law, US marshals and judges would be withdrawn. No mention was made of bullion lost from mints. He stated that it would be US policy "to collect the duties and imposts"; "there will be no invasion, no using of force against or among the people anywhere" that would justify an armed revolution. His speech closed with a plea for restoration of the bonds of union, famously calling on "the mystic chords of memory" binding the two regions.

The Davis government of the new Confederacy sent delegates to Washington to negotiate a peace treaty. Lincoln rejected negotiations, because he claimed that the Confederacy was not a legitimate government and to make a treaty with it would recognize it as such. Lincoln instead attempted to negotiate directly with the governors of seceded states, whose administrations he continued to recognize.

Complicating Lincoln's attempts to defuse the crisis was Secretary of State William H. Seward, who had been Lincoln's rival for the Republican nomination. Embittered by his defeat, Seward agreed to support Lincoln's candidacy only after he was guaranteed the executive office then considered the second most powerful. In the early stages of Lincoln's presidency Seward held little regard for him, due to his perceived inexperience. Seward viewed himself as the de facto head of government, the "prime minister" behind the throne. Seward attempted to engage in unauthorized and indirect negotiations that failed. Lincoln was determined to hold all remaining Union-occupied forts in the Confederacy: Fort Monroe in Virginia, Fort Pickens, Fort Jefferson, and Fort Taylor in Florida, and Fort Sumter in South Carolina.

Battle of Fort Sumter

The American Civil War began on April 12, 1861, when Confederate forces opened fire on the Union-held Fort Sumter. Fort Sumter is located in the harbor of Charleston, South Carolina. Its status had been contentious for months. Outgoing President Buchanan had dithered in reinforcing its garrison, commanded by Major Robert Anderson. Anderson took matters into his own hands and on December 26, 1860, under the cover of darkness, sailed the garrison from the poorly placed Fort Moultrie to the stalwart island Fort Sumter. Anderson's actions catapulted him to hero status in the North. An attempt to resupply the fort on January 9, 1861, failed and nearly started the war then, but an informal truce held. On March 5, Lincoln was informed the fort was low on supplies.

Fort Sumter proved a key challenge to Lincoln's administration. Back-channel dealing by Seward with the Confederates undermined Lincoln's decision-making; Seward wanted to pull out. But a firm hand by Lincoln tamed Seward, who was a staunch Lincoln ally. Lincoln decided holding the fort, which would require reinforcing it, was the only workable option. On April 6, Lincoln informed the Governor of South Carolina that a ship with food but no ammunition would attempt to supply the fort. Historian McPherson describes this win-win approach as "the first sign of the mastery that would mark Lincoln's presidency"; the Union would win if it could resupply and hold the fort, and the South would be the aggressor if it opened fire on an unarmed ship supplying starving men. An April 9 Confederate cabinet meeting resulted in Davis ordering General P. G. T. Beauregard to take the fort before supplies reached it.

At 4:30 am on April 12, Confederate forces fired the first of 4,000 shells at the fort; it fell the next day. The loss of Fort Sumter lit a patriotic fire under the North. On April 15, Lincoln called on the states to field 75,000 volunteer troops for 90 days; impassioned Union states met the quotas quickly. On May 3, 1861, Lincoln called for an additional 42,000 volunteers for three years. Shortly after this, Virginia, Tennessee, Arkansas, and North Carolina seceded and joined the Confederacy. To reward Virginia, the Confederate capital was moved to Richmond.

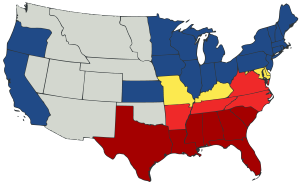

Attitude of the border states

Maryland, Delaware, Missouri, West Virginia and Kentucky were slave states whose people had divided loyalties to Northern and Southern businesses and family members. Some men enlisted in the Union Army and others in the Confederate Army. West Virginia separated from Virginia and was admitted to the Union on June 20, 1863, though half its counties were secessionist.

Maryland's territory surrounded Washington, D.C., and could cut it off from the North. It had anti-Lincoln officials who tolerated anti-army rioting in Baltimore and the burning of bridges, both aimed at hindering the passage of troops to the South. Maryland's legislature voted overwhelmingly to stay in the Union, but rejected hostilities with its southern neighbors, voting to close Maryland's rail lines to prevent their use for war. Lincoln responded by establishing martial law and unilaterally suspending habeas corpus in Maryland, along with sending in militia units. Lincoln took control of Maryland and the District of Columbia by seizing prominent figures, including arresting one-third of the members of the Maryland General Assembly on the day it reconvened. All were held without trial, with Lincoln ignoring a ruling on June 1, 1861, by Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger Taney, not speaking for the Court, that only Congress could suspend habeas corpus (Ex parte Merryman). Federal troops imprisoned a Baltimore newspaper editor, Frank Key Howard, after he criticized Lincoln in an editorial for ignoring Taney's ruling.

In Missouri, an elected convention on secession voted to remain in the Union. When pro-Confederate Governor Claiborne Fox Jackson called out the state militia, it was attacked by federal forces under General Nathaniel Lyon, who chased the governor and rest of the State Guard to the southwestern corner of Missouri (see Missouri secession). Early in the war the Confederacy controlled southern Missouri through the Confederate government of Missouri but was driven out after 1862. In the resulting vacuum, the convention on secession reconvened and took power as the Unionist provisional government of Missouri.

Kentucky did not secede, it declared itself neutral. When Confederate forces entered in September 1861, neutrality ended and the state reaffirmed its Union status while maintaining slavery. During an invasion by Confederate forces in 1861, Confederate sympathizers and delegates from 68 Kentucky counties organized the secession Russellville Convention, formed the shadow Confederate Government of Kentucky, inaugurated a governor, and Kentucky was admitted into the Confederacy on December 10, 1861. Its jurisdiction extended only as far as Confederate battle lines in the Commonwealth, which at its greatest extent was over half the state, and it went into exile after October 1862.

After Virginia's secession, a Unionist government in Wheeling asked 48 counties to vote on an ordinance to create a new state in October 1861. A voter turnout of 34% approved the statehood bill (96% approving). Twenty-four secessionist counties were included in the new state, and the ensuing guerrilla war engaged about 40,000 federal troops for much of the war. Congress admitted West Virginia to the Union on June 20, 1863. West Virginians provided about 20,000 soldiers to each side in the war. A Unionist secession attempt occurred in East Tennessee, but was suppressed by the Confederacy, which arrested over 3,000 men suspected of loyalty to the Union; they were held without trial.

War

The Civil War was marked by intense and frequent battles. Over four years, 237 named battles were fought, along with many smaller actions, often characterized by their bitter intensity and high casualties. Historian John Keegan described it as "one of the most ferocious wars ever fought," where, in many cases, the only target was the enemy's soldiers.

Mobilization

As the Confederate states organized, the U.S. Army numbered 16,000, while Northern governors began mobilizing their militias. The Confederate Congress authorized up to 100,000 troops in February. By May, Jefferson Davis was pushing for another 100,000 soldiers for one year or the duration, and the U.S. Congress responded in kind.

In the first year of the war, both sides had more volunteers than they could effectively train and equip. After the initial enthusiasm faded, relying on young men who came of age each year was not enough. Both sides enacted draft laws (conscription) to encourage or force volunteering, though relatively few were drafted. The Confederacy passed a draft law in April 1862 for men aged 18–35, with exemptions for overseers, government officials, and clergymen. The U.S. Congress followed in July, authorizing a militia draft within states that could not meet their quota with volunteers. European immigrants joined the Union Army in large numbers, including 177,000 born in Germany and 144,000 in Ireland. About 50,000 Canadians served, around 2,500 of whom were black.

When the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect in January 1863, ex-slaves were energetically recruited to meet state quotas. States and local communities offered higher cash bonuses for white volunteers. Congress tightened the draft law in March 1863. Men selected in the draft could provide substitutes or, until mid-1864, pay commutation money. Many eligibles pooled their money to cover the cost of anyone drafted. Families used the substitute provision to select which man should go into the army and which should stay home. There was much evasion and resistance to the draft, especially in Catholic areas. The New York City draft riots in July 1863 involved Irish immigrants who had been signed up as citizens to swell the vote of the city's Democratic political machine, not realizing it made them liable for the draft. Of the 168,649 men procured for the Union through the draft, 117,986 were substitutes, leaving only 50,663 who were conscripted.

In the North and South, draft laws were highly unpopular. In the North, some 120,000 men evaded conscription, many fleeing to Canada, and another 280,000 soldiers deserted during the war. At least 100,000 Southerners deserted, about 10 percent of the total. Southern desertion was high because many soldiers were more concerned about the fate of their local area than the Southern cause. In the North, "bounty jumpers" enlisted to collect the generous bonus, deserted, then re-enlisted under a different name for a second bonus; 141 were caught and executed.

From a tiny frontier force in 1860, the Union and Confederate armies grew into the "largest and most efficient armies in the world" within a few years. Some European observers at the time dismissed them as amateur and unprofessional, but historian John Keegan concluded that each outmatched the French, Prussian, and Russian armies, and without the Atlantic, could have threatened any of them with defeat.

Southern Unionists

Unionism was strong in certain areas within the Confederacy. As many as 100,000 men living in states under Confederate control served in the Union Army or pro-Union guerrilla groups. Although they came from all classes, most Southern Unionists differed socially, culturally, and economically from their region’s dominant prewar, slave-owning planter class.

Prisoners

At the war's start, a parole system operated, under which captives agreed not to fight until exchanged. They were held in camps run by their army, paid, but not allowed to perform any military duties. The system of exchanges collapsed in 1863 when the Confederacy refused to exchange black prisoners. After that, about 56,000 of the 409,000 POWs died in prisons, accounting for 10 percent of the conflict's fatalities.

Women

Historian Elizabeth D. Leonard writes that between 500 and 1,000 women enlisted as soldiers on both sides, disguised as men. Women also served as spies, resistance activists, nurses, and hospital personnel. Women served on the Union hospital ship Red Rover and nursed Union and Confederate troops at field hospitals. Mary Edwards Walker, the only woman ever to receive the Medal of Honor, served in the Union Army and was given the medal for treating the wounded during the war. One woman, Jennie Hodgers, fought for the Union under the name Albert D. J. Cashier. After she returned to civilian life, she continued to live as a man until she died in 1915 at the age of 71.

Naval tactics

The small U.S. Navy of 1861 rapidly expanded to 6,000 officers and 45,000 sailors by 1865, with 671 vessels totaling 510,396 tons. Its mission was to blockade Confederate ports, control the river system, defend against Confederate raiders on the high seas, and be ready for a possible war with the British Royal Navy. The main riverine war was fought in the West, where major rivers gave access to the Confederate heartland. The U.S. Navy eventually controlled the Red, Tennessee, Cumberland, Mississippi, and Ohio rivers. In the East, the Navy shelled Confederate forts and supported coastal army operations.

The Civil War occurred during the early stages of the industrial revolution, leading to naval innovations, notably the ironclad warship. The Confederacy, recognizing the need to counter the Union's naval superiority, built or converted over 130 vessels, including 26 ironclads. Despite these efforts, Confederate ships were largely unsuccessful against Union ironclads. The Union Navy used timberclads, tinclads, and armored gunboats. Shipyards in Cairo, Illinois, and St. Louis built or modified steamboats.

The Confederacy experimented with the submarine CSS Hunley, which was not successful, and with the ironclad CSS Virginia, rebuilt from the sunken Union ship Merrimack. On March 8, 1862, Virginia inflicted significant damage on the Union's wooden fleet, but the next day, the first Union ironclad, USS Monitor, arrived to challenge it in the Chesapeake Bay. The resulting three-hour Battle of Hampton Roads was a draw, proving ironclads were effective warships. The Confederacy scuttled the Virginia to prevent its capture, while the Union built many copies of the Monitor. The Confederacy's efforts to obtain warships from Great Britain failed, as Britain had no interest in selling warships to a nation at war with a stronger enemy and feared souring relations with the U.S.

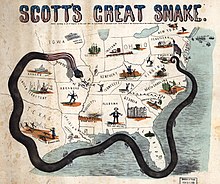

Union blockade

By early 1861, General Winfield Scott had devised the Anaconda Plan to win the war with minimal bloodshed, calling for a blockade of the Confederacy to suffocate the South into surrender. Lincoln adopted parts of the plan but opted for a more active war strategy. In April 1861, Lincoln announced a blockade of all Southern ports; commercial ships could not get insurance, ending regular traffic. The South blundered by embargoing cotton exports before the blockade was fully effective; by the time they reversed this decision, it was too late. "King Cotton" was dead, as the South could export less than 10% of its cotton. The blockade shut down the ten Confederate seaports with railheads that moved almost all the cotton. By June 1861, warships were stationed off the principal Southern ports, and a year later nearly 300 ships were in service.

Blockade runners

The Confederates began the war short on military supplies, which the agrarian South could not produce. Northern arms manufacturers were restricted by an embargo, ending existing and future contracts with the South. The Confederacy turned to foreign sources, connecting with financiers and companies like S. Isaac, Campbell & Company and the London Armoury Company in Britain, becoming the Confederacy's main source of arms.

To transport arms safely to the Confederacy, British investors built small, fast, steam-driven blockade runners that traded arms and supplies from Britain, through Bermuda, Cuba, and the Bahamas in exchange for high-priced cotton. Many were lightweight and designed for speed, only carrying small amounts of cotton back to England. When the Union Navy seized a blockade runner, the ship and cargo were condemned as a prize of war and sold, with proceeds given to the Navy sailors; the captured crewmen, mostly British, were released.

Economic impact

The Southern economy nearly collapsed during the war due to multiple factors, the most notable being severe food shortages, failing railroads, loss of control over key rivers, foraging by Northern armies, and the seizure of animals and crops by Confederate forces. Historians agree the blockade was a major factor in ruining the Confederate economy; however, Wise argues blockade runners provided enough of a lifeline to allow Lee to continue fighting for additional months, thanks to supplies like 400,000 rifles, lead, blankets, and boots that the homefront economy could no longer supply.

Surdam contends that the blockade was a powerful weapon that eventually ruined the Southern economy, costing few lives in combat. The Confederate cotton crop became nearly useless, cutting off the Confederacy's primary income source. Critical imports were scarce, and coastal trade largely ended as well. The blockade's success was not measured by the few ships that slipped through but by the thousands that never tried. European merchant ships could not get insurance and were too slow to evade the blockade, so they stopped calling at Confederate ports.

To fight an offensive war, the Confederacy purchased arms in Britain and converted British-built ships into commerce raiders. The smuggling of 600,000 arms enabled the Confederacy to fight on for two more years, and the commerce raiders targeted U.S. Merchant Marine ships in the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Insurance rates soared, and the American flag virtually disappeared from international waters, though reflagging ships with European flags allowed them to continue operating unmolested. After the war, the U.S. government demanded Britain compensate it for the damage caused by blockade runners and raiders outfitted in British ports. Britain paid the U.S. $15 million in 1871, but only for commerce raiding.

Dinçaslan argues that another outcome of the blockade was the rise of oil as a prominent commodity. The declining whale oil industry took a blow as many old whaling ships were used in blockade efforts, such as the Stone Fleet, and Confederate raiders harassed Union whalers. Oil products, especially kerosene, began replacing whale oil in lamps, increasing oil's importance long before it became fuel for combustion engines.

Diplomacy

Although the Confederacy hoped Britain and France would join them against the Union, this was never likely, so they sought to bring them in as mediators. The Union worked to block this and threatened war if any country recognized the Confederacy. In 1861, Southerners voluntarily embargoed cotton shipments, hoping to start an economic depression in Europe that would force Britain to enter the war, but this failed. Worse, Europe turned to Egypt and India for cotton, which they found superior, hindering the South's post-war recovery.

Cotton diplomacy proved a failure as Europe had a surplus of cotton, while the 1860–62 crop failures in Europe made the North's grain exports critically important. It also helped turn European opinion against the Confederacy. It was said that "King Corn was more powerful than King Cotton," as U.S. grain went from a quarter to almost half of British imports. Meanwhile, the war created jobs for arms makers, ironworkers, and ships to transport weapons.

Lincoln's administration initially struggled to appeal to European public opinion. At first, diplomats explained that the U.S. was not committed to ending slavery and emphasized legal arguments about the unconstitutionality of secession. Confederate representatives, however, focused on their struggle for liberty, commitment to free trade, and the essential role of cotton in the European economy. The European aristocracy was "absolutely gleeful in pronouncing the American debacle as proof that the entire experiment in popular government had failed. European government leaders welcomed the fragmentation of the ascendant American Republic." However, a European public with liberal sensibilities remained, which the U.S. sought to appeal to by building connections with the international press. By 1861, Union diplomats like Carl Schurz realized emphasizing the war against slavery was the Union's most effective moral asset in swaying European public opinion. Seward was concerned an overly radical case for reunification would distress European merchants with cotton interests; even so, he supported a widespread campaign of public diplomacy.

U.S. minister to Britain Charles Francis Adams proved adept and convinced Britain not to challenge the Union blockade. The Confederacy purchased warships from commercial shipbuilders in Britain, with the most famous being the CSS Alabama, which caused considerable damage and led to serious postwar disputes. However, public opinion against slavery in Britain created a political liability for politicians, where the anti-slavery movement was powerful.

War loomed in late 1861 between the U.S. and Britain over the Trent affair, which began when U.S. Navy personnel boarded the British ship Trent and seized two Confederate diplomats. However, London and Washington smoothed this over after Lincoln released the two men. Prince Albert left his deathbed to issue diplomatic instructions to Lord Lyons during the Trent affair. His request was honored, and, as a result, the British response to the U.S. was toned down, helping avert war. In 1862, the British government considered mediating between the Union and Confederacy, though such an offer would have risked war with the U.S. British Prime Minister Lord Palmerston reportedly read Uncle Tom's Cabin three times when deciding what his decision would be.

The Union victory at the Battle of Antietam caused the British to delay this decision. The Emancipation Proclamation increased the political liability of supporting the Confederacy. Realizing that Washington could not intervene in Mexico as long as the Confederacy controlled Texas, France invaded Mexico in 1861 and installed the Habsburg Austrian archduke Maximilian I as emperor. Washington repeatedly protested France's violation of the Monroe Doctrine. Despite sympathy for the Confederacy, France's seizure of Mexico ultimately deterred it from war with the Union. Confederate offers late in the war to end slavery in return for diplomatic recognition were not seriously considered by London or Paris. After 1863, the Polish revolt against Russia further distracted the European powers and ensured they remained neutral.

Russia supported the Union, largely because it believed the U.S. served as a counterbalance to its geopolitical rival, the U.K. In 1863, the Imperial Russian Navy's Baltic and Pacific fleets wintered in the American ports of New York and San Francisco, respectively.

Eastern theater

The Eastern theater refers to the military operations east of the Appalachian Mountains, including Virginia, West Virginia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania, the District of Columbia, and the coastal fortifications and seaports of North Carolina.

Background

Army of the Potomac

Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan took command of the Union Army of the Potomac on July 26, 1861, and the war began in earnest in 1862. The 1862 Union strategy called for simultaneous advances along four axes:

- McClellan would lead the main thrust in Virginia towards Richmond.

- Ohio forces would advance through Kentucky into Tennessee.

- The Missouri Department would drive south along the Mississippi River.

- The westernmost attack would originate from Kansas.

Army of Northern Virginia

The primary Confederate force in the Eastern theater was the Army of Northern Virginia. The Army originated as the (Confederate) Army of the Potomac, which was organized on June 20, 1861, from all operational forces in Northern Virginia. On July 20 and 21, the Army of the Shenandoah and forces from the District of Harpers Ferry were added. Units from the Army of the Northwest were merged into the Army of the Potomac between March 14 and May 17, 1862. The Army of the Potomac was renamed Army of Northern Virginia on March 14. The Army of the Peninsula was merged into it on April 12, 1862.

When Virginia declared its secession in April 1861, Robert E. Lee chose to follow his home state, despite his desire for the country to remain intact and an offer of a senior Union command. Lee's biographer, Douglas S. Freeman, asserts that the army received its final name from Lee when he issued orders assuming command on June 1, 1862. However, Freeman does admit that Lee corresponded with Brigadier General Joseph E. Johnston, his predecessor in army command, before that date and referred to Johnston's command as the Army of Northern Virginia. Part of the confusion results from the fact Johnston commanded the Department of Northern Virginia (as of October 22, 1861) and the name Army of Northern Virginia can be seen as an informal consequence of its parent department's name. Jefferson Davis and Johnston did not adopt the name, but it is clear the organization of units as of March 14 was the same organization that Lee received on June 1, and thus it is generally referred to today as the Army of Northern Virginia, even if that is correct only in retrospect.

On July 4 at Harper's Ferry, Colonel Thomas J. Jackson assigned Jeb Stuart to command all the cavalry companies of the Army of the Shenandoah. He eventually commanded the Army of Northern Virginia's cavalry.

Battles

In July 1861, in of the first highly visible battles, Union troops under the command of Maj. Gen. Irvin McDowell attacking Confederate forces led by Beauregard near Washington were repulsed at the First Battle of Bull Run.

The Union had the upper hand at first, nearly pushing Confederate forces holding a defensive position into a rout, but Confederate reinforcements under Joseph E. Johnston arrived from the Shenandoah Valley by railroad, and the course of the battle quickly changed. A brigade of Virginians under the relatively unknown brigadier general from the Virginia Military Institute, Thomas J. Jackson, stood its ground, which resulted in Jackson's receiving his famous nickname, "Stonewall".

Upon the urging of Lincoln to begin offensive operations, McClellan attacked Virginia in the spring of 1862 by way of the peninsula between the York River and James River, southeast of Richmond. McClellan's army reached the gates of Richmond in the Peninsula campaign.

Also in the spring of 1862, in the Shenandoah Valley, Stonewall Jackson led his Valley Campaign. Audaciously employing rapid, unpredictable movements on interior lines, Jackson's 17,000 troops marched 646 miles (1,040 km) in 48 days and won minor battles as they successfully engaged three Union armies (52,000 men), including those of Nathaniel P. Banks and John C. Fremont, preventing them from reinforcing the Union offensive against Richmond. The swiftness of Jackson's men earned them the nickname of "foot cavalry".

Johnston halted McClellan's advance at the Battle of Seven Pines, but he was wounded in the battle, and Robert E. Lee assumed his position of command. Lee and top subordinates James Longstreet and Stonewall Jackson defeated McClellan in the Seven Days Battles and forced his retreat.

The Northern Virginia Campaign, which included the Second Battle of Bull Run, ended in yet another victory for the South. McClellan resisted General-in-Chief Halleck's orders to send reinforcements to John Pope's Union Army of Virginia, which made it easier for Lee's Confederates to defeat twice the number of combined enemy troops.

Emboldened by Second Bull Run, the Confederacy made its first invasion of the North with the Maryland Campaign. Lee led 45,000 troops of the Army of Northern Virginia across the Potomac River into Maryland on September 5. Lincoln then restored Pope's troops to McClellan. McClellan and Lee fought at the Battle of Antietam near Sharpsburg, Maryland, on September 17, 1862, the bloodiest single day in US military history. Lee's army, checked at last, returned to Virginia before McClellan could destroy it. Antietam is considered a Union victory because it halted Lee's invasion of the North and provided an opportunity for Lincoln to announce his Emancipation Proclamation.

When the cautious McClellan failed to follow up on Antietam, he was replaced by Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside. Burnside was defeated at the Battle of Fredericksburg on December 13, 1862, when more than 12,000 Union soldiers were killed or wounded during futile frontal assaults against Marye's Heights. After the battle, Burnside was replaced by Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker.

Hooker, too, proved unable to defeat Lee's army; despite outnumbering the Confederates by more than two to one, his Chancellorsville Campaign proved ineffective, and he was humiliated in the Battle of Chancellorsville in May 1863. Chancellorsville is known as Lee's "perfect battle" because his risky decision to divide his army in the presence of a much larger enemy force resulted in a significant Confederate victory. Stonewall Jackson was shot in the left arm and right hand by friendly fire during the battle. The arm was amputated, but he died of pneumonia. Lee famously said: "He has lost his left arm, but I have lost my right arm."

The fiercest fighting of the battle—and the second bloodiest day of the Civil War—occurred on May 3 as Lee launched multiple attacks against the Union position at Chancellorsville. That same day, John Sedgwick advanced across the Rappahannock River, defeated the small Confederate force at Marye's Heights in the Second Battle of Fredericksburg, and then moved to the west. The Confederates fought a successful delaying action at the Battle of Salem Church.

Gen. Hooker was replaced by Maj. Gen. George Meade during Lee's second invasion of the North, in June. Meade defeated Lee at the Battle of Gettysburg (July 1863). This was the bloodiest battle and has been called the war's turning point. Pickett's Charge on July 3 is considered the high-water mark of the Confederacy because it signaled the collapse of serious Confederate threats of victory. Lee's army suffered 28,000 casualties, versus Meade's 23,000.

Western theater

The Western theater refers to military operations between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River, including Alabama, Georgia, Florida, Mississippi, North Carolina, Kentucky, South Carolina, Tennessee, and parts of Louisiana.

Background

Army of the Tennessee and Army of the Cumberland

The primary Union forces in this theater were the Army of the Tennessee and Army of the Cumberland, named for the two rivers, Tennessee River and Cumberland River. After Meade's inconclusive fall campaign, Lincoln turned to the Western theater for new leadership. At the same time, the Confederate stronghold of Vicksburg surrendered, giving the Union control of the Mississippi River, permanently isolating the western Confederacy, and producing the new leader Lincoln needed, Ulysses S. Grant.

Army of Tennessee

The primary Confederate force in the Western theater was the Army of Tennessee. The army was formed on November 20, 1862, when General Braxton Bragg renamed the former Army of Mississippi. While the Confederate forces had successes in the Eastern theater, they were defeated many times in the West.

Battles

The Union's key strategist and tactician in the West was Ulysses S. Grant, who won victories at Forts Henry (February 6, 1862) and Donelson (February 11 to 16, 1862), earning him the nickname of "Unconditional Surrender" Grant. With these victories the Union gained control of the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers. Nathan Bedford Forrest rallied nearly 4,000 Confederate troops and led them to escape across the Cumberland. Nashville and central Tennessee thus fell to the Union, leading to attrition of local food supplies and livestock and a breakdown in social organization.

Confederate general Leonidas Polk's invasion of Columbus ended Kentucky's policy of neutrality and turned it against the Confederacy. Grant used river transport and Andrew Hull Foote's gunboats of the Western Flotilla, to threaten the Confederacy's "Gibraltar of the West" at Columbus, Kentucky. Although rebuffed at Belmont, Grant cut off Columbus. The Confederates, lacking their gunboats, were forced to retreat and the Union took control of west Kentucky and opened Tennessee in March 1862.

At the Battle of Shiloh, in Shiloh, Tennessee in April 1862, the Confederates made a surprise attack that pushed Union forces against the river as night fell. Overnight, the Navy landed reinforcements, and Grant counterattacked. Grant and the Union won a decisive victory—the first battle with the high casualty rates that would occur repeatedly. The Confederates lost Albert Sidney Johnston, considered their finest general before the emergence of Lee.

One of the early Union objectives was to capture the Mississippi River to cut the Confederacy in half. The Mississippi was opened to Union traffic to the southern border of Tennessee with the taking of Island No. 10 and New Madrid, Missouri, and then Memphis, Tennessee.

In April 1862, the Union Navy captured New Orleans. "The key to the river was New Orleans, the South's largest port [and] greatest industrial center." U.S. Naval forces under Farragut ran past Confederate defenses south of New Orleans. Confederate forces abandoned the city, giving the Union a critical anchor in the deep South, which allowed Union forces to move up the Mississippi. Memphis fell to Union forces on June 6, 1862, and became a key base for further advances south along the Mississippi. Only the fortress city of Vicksburg, Mississippi, prevented Union control of the entire river.

Bragg's second invasion of Kentucky in the Confederate Heartland Offensive included initial successes such as Kirby Smith's triumph at the Battle of Richmond and the capture of the Kentucky capital of Frankfort on September 3, 1862. However, the campaign ended with a meaningless victory over Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell at the Battle of Perryville. Bragg was forced to end his attempt at invading Kentucky and retreat, due to lack of logistical support and infantry recruits. Bragg was narrowly defeated by Maj. Gen. William Rosecrans at the Battle of Stones River in Tennessee, the culmination of the Stones River Campaign.

Naval forces assisted Grant in the long, complex Vicksburg Campaign that resulted in the Confederates surrendering at the Battle of Vicksburg in July 1863, which cemented Union control of the Mississippi and is one of the turning points of the war.

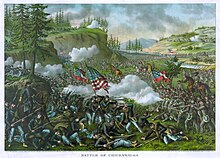

The one clear Confederate victory in the West was the Battle of Chickamauga. After Rosecrans' successful Tullahoma Campaign, Bragg, reinforced by Lt. Gen. James Longstreet's corps, defeated Rosecrans, despite the defensive stand of Maj. Gen. George Henry Thomas.

Rosecrans retreated to Chattanooga, which Bragg then besieged in the Chattanooga Campaign. Grant marched to the relief of Rosecrans and defeated Bragg at the Third Battle of Chattanooga, eventually causing Longstreet to abandon his Knoxville Campaign and driving Confederate forces out of Tennessee and opening a route to Atlanta and the heart of the Confederacy.

Trans-Mississippi theater

Background

The Trans-Mississippi theater refers to military operations west of the Mississippi, encompassing most of Missouri, Arkansas, most of Louisiana, and the Indian Territory in present-day Oklahoma. The Trans-Mississippi District was formed by the Confederate States Army to better coordinate Ben McCulloch's command of troops in Arkansas and Louisiana, Sterling Price's Missouri State Guard, as well as the portion of Earl Van Dorn's command that included the Indian Territory and excluded the Army of the West. The Union's command was the Trans-Mississippi Division, or the Military Division of West Mississippi.

Battles

The first battle of the Trans-Mississippi theater was the Battle of Wilson's Creek (August 1861). The Confederates were driven from Missouri early in the war as a result of the Battle of Pea Ridge.

Extensive guerrilla warfare characterized the trans-Mississippi region, as the Confederacy lacked the troops and logistics to support regular armies that could challenge Union control. Roving Confederate bands such as Quantrill's Raiders terrorized the countryside, striking military installations and civilian settlements. The "Sons of Liberty" and "Order of the American Knights" attacked pro-Union people, elected officeholders, and unarmed uniformed soldiers. These partisans could not be driven out of Missouri, until an entire regular Union infantry division was engaged. By 1864, these violent activities harmed the nationwide antiwar movement organizing against the re-election of Lincoln. Missouri not only stayed in the Union, but Lincoln took 70 percent of the vote to win re-election.

Small-scale military actions south and west of Missouri sought to control Indian Territory and New Mexico Territory for the Union. The Battle of Glorieta Pass was the decisive battle of the New Mexico Campaign. The Union repulsed Confederate incursions into New Mexico in 1862, and the exiled Arizona government withdrew into Texas. In the Indian Territory, civil war broke out within tribes. About 12,000 Indian warriors fought for the Confederacy but fewer for the Union. The most prominent Cherokee was Brigadier General Stand Watie, the last Confederate general to surrender.

After the fall of Vicksburg in July 1863, Jefferson Davis informed General Kirby Smith in Texas that he could expect no further help from east of the Mississippi. Although he lacked resources to beat Union armies, he built up a formidable arsenal at Tyler, along with his own Kirby Smithdom economy, a virtual "independent fiefdom" in Texas, including railroad construction and international smuggling. The Union, in turn, did not directly engage him. Its 1864 Red River Campaign to take Shreveport, Louisiana, failed and Texas remained in Confederate hands throughout the war.

Lower seaboard theater

Background

The lower seaboard theater refers to military and naval operations that occurred near the coastal areas of the Southeast as well as the southern part of the Mississippi. Union naval activities were dictated by the Anaconda Plan.

Battles

One of the earliest battles was fought at Port Royal Sound (November 1861), south of Charleston. Much of the war along the South Carolina coast concentrated on capturing Charleston. In attempting to capture Charleston, the Union military tried two approaches: by land over James or Morris Islands or through the harbor. However, the Confederates were able to drive back each attack. A famous land attack was the Second Battle of Fort Wagner, in which the 54th Massachusetts Infantry took part. The Union suffered a serious defeat, losing 1,515 soldiers while the Confederates lost only 174. However, the 54th was hailed for its valor, which encouraged the general acceptance of the recruitment of African American soldiers into the Union Army, which reinforced the Union's numerical advantage.

Fort Pulaski on the Georgia coast was an early target for the Union navy. Following the capture of Port Royal, an expedition was organized with engineer troops under the command of Captain Quincy Adams Gillmore, forcing a Confederate surrender. The Union army occupied the fort for the rest of the war after repairing it.

In April 1862, a Union naval task force commanded by Commander David Dixon Porter attacked Forts Jackson and St. Philip, which guarded the river approach to New Orleans from the south. While part of the fleet bombarded the forts, other vessels forced a break in the obstructions in the river and enabled the rest of the fleet to steam upriver to the city. A Union army force commanded by Major General Benjamin Butler landed near the forts and forced their surrender. Butler's controversial command of New Orleans earned him the nickname "Beast".

The following year, the Union Army of the Gulf commanded by Major General Nathaniel P. Banks laid siege to Port Hudson for nearly eight weeks, the longest siege in US military history. The Confederates attempted to defend with the Bayou Teche Campaign but surrendered after Vicksburg. These surrenders gave the Union control over the Mississippi.

Several small skirmishes but no major battles were fought in Florida. The biggest was the Battle of Olustee in early 1864.

Pacific coast theater

The Pacific coast theater refers to military operations on the Pacific Ocean and in the states and Territories west of the Continental Divide.

Conquest of Virginia

At the beginning of 1864, Lincoln made Grant commander of all Union armies. Grant made his headquarters with the Army of the Potomac and put Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman in command of most of the western armies. Grant understood the concept of total war and believed, along with Lincoln and Sherman, that only the utter defeat of Confederate forces and their economic base would end the war. This was total war not in killing civilians, but in taking provisions and forage and destroying homes, farms, and railroads, that Grant said "would otherwise have gone to the support of secession and rebellion. This policy I believe exercised a material influence in hastening the end."

Grant devised a coordinated strategy that would strike at the entire Confederacy from multiple directions. Generals Meade and Benjamin Butler were ordered to move against Lee near Richmond, General Franz Sigel was to attack the Shenandoah Valley, General Sherman was to capture Atlanta and march to the Atlantic Ocean, Generals George Crook and William W. Averell were to operate against railroad supply lines in West Virginia, and Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks was to capture Mobile, Alabama.

Grant's Overland Campaign

Grant's army set out on the Overland Campaign intending to draw Lee into a defense of Richmond, where they would attempt to pin down and destroy the Confederate army. The Union army first attempted to maneuver past Lee and fought several battles, notably at the Wilderness, Spotsylvania, and Cold Harbor. These resulted in heavy losses on both sides and forced Lee's Confederates to fall back repeatedly. At the Battle of Yellow Tavern, the Confederates lost Jeb Stuart.

An attempt to outflank Lee from the south failed under Butler, who was trapped inside the Bermuda Hundred river bend. Each battle resulted in setbacks for the Union that mirrored those they had suffered under prior generals, though unlike them, Grant chose to fight on rather than retreat. Grant was tenacious and kept pressing Lee's Army of Northern Virginia back to Richmond. While Lee was preparing for an attack on Richmond, Grant unexpectedly turned south to cross the James River and began the protracted Siege of Petersburg, where the two armies engaged in trench warfare for over nine months.

Sheridan's Valley Campaign

To deny the Confederacy continued use of the Shenandoah Valley as a base from which to launch invasions of Maryland and the Washington area, and to threaten Lee's supply lines for his forces, Grant launched the Valley campaigns in the spring of 1864. Initial efforts led by Gen. Sigel were repelled at the Battle of New Market by Confederate Gen. John C. Breckinridge. The Battle of New Market was the Confederacy's last major victory, and included a charge by teenage VMI cadets. After relieving Sigel, and following mixed performances by his successor, Grant finally found a commander, General Philip Sheridan, aggressive enough to prevail against the army of Maj. Gen. Jubal A. Early. After a cautious start, Sheridan defeated Early in a series of battles in September and October 1864, including a decisive defeat at the Battle of Cedar Creek. Sheridan then proceeded through that winter to destroy the agricultural base of the Shenandoah Valley, a strategy similar to the tactics Sherman later employed in Georgia.

Sherman's March to the Sea

Meanwhile, Sherman maneuvered from Chattanooga to Atlanta, defeating Confederate Generals Joseph E. Johnston and John Bell Hood. The fall of Atlanta on September 2, 1864, guaranteed the reelection of Lincoln. Hood left the Atlanta area to swing around and menace Sherman's supply lines and invade Tennessee in the Franklin–Nashville Campaign. Union Maj. Gen. John Schofield defeated Hood at the Battle of Franklin, and George H. Thomas dealt Hood a massive defeat at the Battle of Nashville, effectively destroying Hood's army.

Leaving Atlanta, and his base of supplies, Sherman's army marched, with no destination set, laying waste to about 20% of the farms in Georgia in his "March to the Sea". He reached the Atlantic at Savannah, Georgia, in December 1864. Sherman's army was followed by thousands of freed slaves; there were no major battles along the march. Sherman turned north through South Carolina and North Carolina, to approach the Confederate Virginia lines from the south, increasing the pressure on Lee's army.

The Waterloo of the Confederacy

Lee's army, thinned by desertion and casualties, was now much smaller than Grant's. One last Confederate attempt to break the Union hold on Petersburg failed at the decisive Battle of Five Forks on April 1. The Union now controlled the entire perimeter surrounding Richmond–Petersburg, completely cutting it off from the Confederacy. Realizing the capital was now lost, Lee's army and the Confederate government were forced to evacuate. The Confederate capital fell on April 2–3, to the Union XXV Corps, composed of black troops. The remaining Confederate units fled west after a defeat at Sayler's Creek on April 6.