Cyril Colnik

He settled in Milwaukee Wisconsin, Colnik opened a workshop there in 1894. He was a pacifist, which lead him to close his business instead of making armaments for World War I. Colnik spent the remainder of his career working in and around Milwaukee, retiring in 1955 and dying in 1958.

Early life

Colnik was born in 1871, in the Austrian village of Trieben, Styria. His parents were Dominick and Anna Rudmilla Colnik; his father was a veterinarian, a politician and an economist. The family lived on a large estate, and from an early age, Colnik spent time around the property's smithy, according to author Alan Strekow.

He apprenticed in the 1880s as a mechanical assistant. He studied iron work in Vienna, and then moved to Graz to study under Franz Roth. He served in the apprenticeship in the metal shop in with Roth after which he studied in France and other countries in Europe, before eventually settling in Munich, Germany. In Munich, he worked in Reinhold Kirsch's workshop. He finished his studies there at the Munich Industrial Art School. Artisan Reinhold Kirsch recognized him as an exceptional student, and sent him to America as part of the German ironworking team at the Chicago World's Columbian Exposition.

Career

When Colnik arrived in Chicago in 1893, he was 22 years old. He worked on the hands of a donated clock for display at the Exposition. Colnik also entered an example of his work. His entry was a grille depicting the patron of blacksmiths: Vulcan, the God of Fire. The grille that he entered is described as a masterpiece by Strekow; he originally created it while still a student in Munich. He received a gold medal for his work depicting Vulcan, and also won a prize for an escutcheon entry. The United States experienced the Panic of 1893 and entered economic depression soon after the exposition, so he never received a physical copy of the medal.

At the Exposition, the brewer Frederick Pabst was showcasing a beer garden. It is thought that Pabst convinced Colnik to move to Southeastern Wisconsin. Colnik created many metal items for the wealthy German brewer, including an intricate wrought-iron and antler chandelier which ended up in a Milwaukee tavern called "Von Trier". Colnik soon opened his own shop in Milwaukee, and between 1894–1905 he gained a reputation for excellent iron work, according to Strekow. His wrought iron factory provided a variety of products for the wealthy residents in the area. Colnik was a pacifist and suspected that his shop may be called upon to make armaments for the war effort during World War I, so he closed his workshop.

During the Great Depression in the 1930s Colnik worked for the Works Progress Administration (WPA). He created the gates for Wisconsin Memorial Park, among other public works. He was admitted to the Wisconsin Chapter of the American Institute of Architects in 1938: the first non-architect to be admitted into the organization.

Colnik was also commissioned to do work for John Ringling, creating the iron work for the John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art. He retired in 1955 at the age of 84. Today, several of his ironwork sketches and photographs are exhibited at the Villa Terrace Decorative Arts Museum in Milwaukee. In 2008 he was given a Wisconsin Visual Art Lifetime Achievement Award.

Personal life

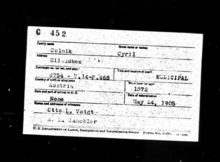

In 1905, Colnik married Marie Charolette (née Merz), the daughter of a Milwaukee shoemaker. On 24 May 1905 Colnik also became a naturalized United States citizen. In 1906 the couple had had a daughter, Gretchen. Colnik died on 25 October 1958 in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, survived by his daughter.

See also

- Jessie and John F. Kern House

- Herman Uihlein House

- St. Paul's Episcopal Church (Milwaukee, Wisconsin)

- Villa Terrace Decorative Arts Museum

Gallery

-

Escutcheon created by Colnik for the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition

-

Front of the grille Colnik created in 1893 in Chicago

-

Detail of the 1893 grille

-

1890-1893 Ornate wrought iron Weinkuhler featuring a face by Cyril Colnik

References

- ^ "Cyril Colnik". Metalsmith. Vol. 18. Society of North American Goldsmiths. 1998. p. 35.

- ^ "Cyril Colnik". The Anvil's Ring. Vol. 22–23. 1994. p. 31.

- ^ Kitchell Whyte, Bertha (1971). Craftsmen of Wisconsin. Racine, Wisconsin: Western Publishing Company. p. 139.

- ^ "Cyril Colnik". Kohler Foundation. Kohler Foundation, Inc. Archived from the original on 5 February 2022. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- ^ Strekow, Alan J. (2011). Cyril Colnik : man of iron (First ed.). Milwaukee, WI: Friends of Villa Terrace Decorative Arts Museum. ISBN 9780615481418.

- ^ "Cyril Colnik Dies: Museum Iron Craftsman". Tampa Bay Times. 14 November 1958. Archived from the original on 18 December 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- ^ Kingsley, John-Duane (February 2022). "The Mozart of Metal: Dan Nauman of 19th-Century Blacksmith Cyril Colnik". The Decorative Arts Trust. Retrieved 15 June 2022.

- ^ "Blacksmith Traditions: Cyril Colnik" (PDF). Blacksmiths of Arkansas. Voice May 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 April 2016. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- ^ Peterson, Gary (6 August 1981). "The Art that Cyril Colnik Wrought Included Peace". The Capital Times. Archived from the original on 18 December 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- ^ The Anvil's Ring – Volumes 9–10. Johnstown, Pennsylvania: Artist-Blacksmiths' Association of North America. 1981. p. 3.

- ^ Buchanan, Mel (29 June 2012). "From the Collection–Cyril Colnik Iron Basket". Milwaukee Art Museum. Archived from the original on 7 March 2022. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- ^ Deptolla, Carol (17 March 2018). "Von Trier bar auctioning off Colnik chandelier, other items". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Archived from the original on 18 December 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- ^ "Cyril Colnik". Wisconsin Visual Art Achievement Awards. Retrieved 15 June 2022.

- ^ "Miss Colnik to Speak May 19". Carbondale Free Press. 9 May 1949. Archived from the original on 18 December 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2021.