Detroit Dry Dock Company

The complex is significant as a historic maritime manufacturing facility. The earliest structure, an 1892 machine shop, is also significant as an early example of an industrial building entirely supported by its steel frame, but using traditional brick and standard windows to infill the curtain walls. The complex was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2009. In 2012, the Department of Natural Resources received funding for historic redevelopment of the complex, along the city's east riverfront promenade.

History

The Dry Dock Engine Works-Detroit Dry Dock Company Complex includes pieces of two once-independent companies—the Dry Dock Engine Works and the Detroit Dry Dock Company—which merged in 1899.

Detroit Dry Dock Company

In the 1840s, Captain Stephen R. Kirby began a shipbuilding firm in Cleveland, Ohio, and by 1852 had moved to Saginaw, Michigan. In 1870, Kirby's son Frank, a Cooper Union-trained engineer, joined the firm as lead designer. (Frank Kirby went on to a successful shipbuilding career, which included the design of two National Historic Landmarks: the Columbia and the Ste. Claire.) In 1872, the Kirby's firm purchased a shipyard in Wyandotte, Michigan.

In 1852, Campbell, Wolverton and Company opened a ship repair yard on the Detroit River at the foot of Orleans Street. In 1860 the firm, now known (with the addition of John Owen as president) as Campbell & Owen, constructed a 260' dry dock in the same location. They constructed their first steamship in 1867.

In 1877, Campbell & Owen reorganized, changing its name to the Detroit Dry Dock Company. At about the same time, Detroit Dry Dock purchased the Kirby's Wyandotte shipbuilding firm. Also in the late 1870s, railroad and shipping magnate James McMillan became interested in shipbuilding, purchasing shares in Detroit Dry Dock. By 1890, McMillan was president of the company, and by 1892 was also president of the nearby Dry Dock Engine Works.

Dry Dock Engine Works

Dry Dock Engine Works, a marine engine manufacturer, was formed in 1866 by William Cowie, Edward Jones, and Robert Donaldson, with Cowie as president. The firm set up shop on Atwater, between Orleans and Dequindre, across from the dry dock firm that was then called Campbell & Owen. The firm slowly acquired surrounding lots, and by 1880 owned nearly the entire city block back to Guoin Street. (The city vacated Dequindre in the vicinity of the Dry Dock Engine Works in 1917, and Guoin some time later; neither street currently exists in the area.)

The main product line of the Dry Dock Engine Works was marine engines, and they produced 129 engines between 1867 and 1894. However, the firm also produced stationary and portable steam engines, as well as mining equipment, mill gearing, and brass and iron casting. In 1883, Dry Dock Engine Works bought the nearby boiler shop of Desotell & Hudson, expanding their product line.

Although unimportant at the time, the Dry Dock Engine Works is significant as an early employer of Henry Ford. The future automobile magnate worked at the firm between 1880 and 1882 as an apprentice machinist. His work with steam engines at the Dry Dock Engine Works inspired in part Ford's later idea of adding an engine to a carriage for road use.

The Dry Dock Engine Works had always had a special relationship with the nearby Detroit Dry Dock Company, which only increased as the years passed. In the 1870s, Dry Dock Engine Works sold over 1/3 of their engines to Detroit Dry Dock; by the early 1890s that fraction had increased to nearly 2/3. The ties were enhanced by the fact that Frank Kirby, John Owen, and James McMillan of Detroit Dry Dock slowly acquired shares in Dry Dock Engine Works. By the end of the 1880s, virtually all of the Dry Dock Engine Works shares were owned by Detroit Dry Dock principals. In 1892, James McMillan took over the presidency of Dry Dock Engine Works, and the two firms were controlled by the same person. It was around this time that the oldest of the remaining structures in the complex, the machine shop and dry dock no. 2, were built.

Integration: Detroit Shipbuilding Company

Although even after 1892 the two firms were technically separate, they essentially operated as a single business unit, with the same principals in charge of both. In 1899, this relationship became more formal, as the Dry Dock Engine Works, the Detroit Dry Dock Company, and the Detroit Sheet Metal and Brass Works were combined to form the Detroit Shipbuilding Company, which itself was a subsidiary of the American Shipbuilding Company headquartered in Cleveland, Ohio. The integration of these operating units created a substantial company: in 1900, the Detroit Shipbuilding Company employed 1337 people, and was the fourth-largest employer in Detroit.

A few years later, in 1902, the Detroit Shipbuilding Company built two more still-surviving structures, the foundry and the industrial loft building. Sometime in the 1910s, three more structures were built, which completed the enclosure of the block where the original Dry Dock Engine Company was founded, and represent the latest of the surviving buildings of the complex.

Shipbuilding continued at the facilities in Wyandotte and Detroit through the 1920s, with a substantial number of ships constructed in the World War I years of 1917-1919. However, business soon decreased and in 1920 the yard in Wyandotte was closed as a cost-cutting measure. Not long afterward, in 1924, a pair of steamers were fitted up in the Detroit yards; these two proved to be the last vessels constructed in Detroit by the American Shipbuilding Company. The Detroit Shipbuilding Company completely ceased operations in 1929.

Use post-maritime construction

The property owned by the Detroit Shipbuilding Company at Atwood and Orleans passed through several hands, being used by a cabinet shop and a stove manufacturer in the early 1930s. In 1935, the property was acquired by the Detroit Edison Company. It is unclear what use, if any, Detroit Edison put the property to in the 1930s and 40s, but in the 1950s and 60s Edison used the engine-building plant as a reconditioning and appliance shop. By 1968, the property was occupied by the Globe Trading Company, a machinery and mill supplies dealer. In 1981, Edison sold the property to Globe. At some time later, the property was abandoned, and by 2002 was empty and owned by the city of Detroit.

Redevelopment

In 2006, a $15-million redevelopment plan was announced, with 45 condominiums and 10,000 square feet (930 m) of ground floor retail space. To facilitate the renovation, in 2007, the city received an Environmental Protection Agency brownfields grant to clean up the building. However, the economic downturn in 2008-2009 forced a reconsideration of the renovation project, and the project plan was converted to incorporate rental units. The redevelopment was intended to be financed in part by the Department of Housing and Urban Development and in part by using historic tax credits, made possible by the inclusion of the complex on the National Register of Historic Places in 2009.

Instead of the proposed housing development, in 2013 the Michigan Department of Natural Resources began renovating the building into the Outdoor Adventure Center. This development involved demolition of portions of the historic building complex. The center opened in 2015.

Buildings and Structures

The Dry Dock Engine Works began manufacturing engines on Atwater Street in 1867; however, the earliest buildings used by the company were replaced by later buildings, built between 1892 and 1919. These early structures were located throughout the city block owned by the company, and included a sheet metal works, boiler shop, forge, machine shop, and the Dry Dock Hotel. The Detroit Dry Dock Company began shipbuilding in the same area as early as 1852. Their earlier dry docks, including Dry Dock No. 1, no longer exist. A complex of six buildings, as well as Dry Dock No. 2, do remain.

Detroit Dry Dock Co. Dry Dock No. 2 (1892)

In 1892, the Detroit Dry Dock Company constructed a new dry dock near the foot of Orleans Street, just west of their original dry dock facility. Dry Dock No. 2 was 378 feet (115 m) long, 20.5 feet (6.2 m) deep below the water line, with a width of between 91 feet (28 m) (at the top) and 55 feet (17 m) (at the bottom). Over two thousand piles were driven into the ground to support the dock. As constructed, the dock could be flooded in twenty minutes and pumped dry in about ninety minutes. The dock was sized to be able to accommodate any vessel traveling on the Great Lakes at that time, and could house even fully loaded vessels.

A monument with sculpture depicting the Dry Dock and the steamer Pioneer is located at the north end of the dry dock.

- Dry Dock No. 2, contemporary and historical images

-

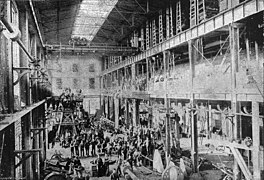

Dry Dock No 2 nearing the end of construction, 1892.

-

Steamer EC Pope in Detroit Dry Dock No 2, c. 1894. Note machine shop in left background and Dry Dock Hotel in right background.

-

Steamer Pioneer in Detroit Dry Dock No 2, 1894.

-

Monument at the site of Detroit Dry Dock No. 2, depicting the steamer Pioneer in the dry dock.

Dry Dock Engine Works Machine Shop (1892)

Also in 1892, Detroit Dry Dock built a machine shop at the corner of Atwater and Orleans, running parallel to Orleans. The shop replaced a portion of the earlier machine shop which fronted on Atwater. The building was designed and built by Berlin Iron Bridge Company, a firm from Connecticut now part of the American Bridge Company. The building featured a load-bearing steel frame and non-load-bearing brick curtain walls, at the time a novel construction technique. Also in 1892, Berlin Iron Bridge also built a boiler shop of the same construction across Dequindre from the main complex; this building has since been demolished.

Description

The machine shop is 200 feet (61 m) long, 66 feet (20 m) wide, and 48 feet (15 m) tall to the top of the wall; a roof monitor extends the height an additional 10 feet (3.0 m). The building consists of thirteen bays dividing the length into 15-foot sections (4.6 m), with the northernmost bay a full 2 feet (0.61 m) wider. Internally, the shop is separated by columns into a 37-foot-wide erecting bay (11 m) running the length of the building on the west side, and a 27-foot-wide lean-to (8.2 m) on the east side.

Pediment walls at each end of the building rise above the roof and are capped with limestone. Two windows per bay were included along the west side. The original windows were replaced sometime between 1912 and 1932. The building originally had two large doorways on the west side; these have since been bricked in. The roof is supported by a series of trusses spaced at nearly 12-foot intervals (3.7 m). A 13-foot-wide roof monitor (4.0 m) runs most of the length of the roof. Although now covered with sheet metal, the sides and roof of the monitor were originally glass.

Background

The 1892 machine shop was constructed to take advantage of what was at the time the most modern innovations applied to manufacturing buildings: electric drive machinery and an electrically driven traveling overhead crane. The tall, wide construction of the building, containing an open space lacking support columns, reflects the desire to implement the crane into the company's manufacturing process. In fact, contemporaneous material from the Detroit Dry Dock Company extols the virtues of the open plan of the building, the "great advantages of light and air" afforded by the skylight and windows, and the effectiveness of the crane.

The open space in the building was possible due to the construction of the building in what was at the time a novel method. Steel frame construction had emerged in 1880s Chicago in the construction of office buildings, the first being the nine-story Home Insurance Building, constructed in 1884. However, the first building to be completely supported by a riveted all-steel frame was the 1889 Rand McNally Building. The steel frame allowed the exterior walls to be reduced to a simple curtain covering the frame, rather than supporting the weight of the building. The Berlin Iron Bridge Company, already experienced in riveted steel construction through their bridge construction, moved into the design and construction of steel-framed industrial buildings at some time in the late 1880s.

Significance

The machine shop is an early example of an industrial building which was entirely supported by a rigid structural steel frame, with exterior walls that were merely a curtain around the structure. This building may very well have been the first such structure in Detroit.

The particular design used by the Berlin Iron Bridge Company represented a conservative, hybrid design. The steel frame completely supported the structure, but the non-load-bearing curtain walls were nonetheless designed the same way as traditional brick load-bearing walls. The windows in the infill were standard-sized windows arranged in a traditional two per bay, side-by-side configuration.

The construction gave the Dry Dock Engine Works the advantages of the open interior space provided by the steel frame construction combined with the more substantial, traditional appearance afforded by the brick exterior. In addition, the brick gave some protection from cold during winter months, with enough windows to maximize the interior light. This particular building exemplifies a link between the traditional past style of industrial architecture and the revolutionary change represented by steel framing.

Eric J. Hill and John Gallagher, in their American Institute of Architects guide to Detroit architecture, state that this building is perhaps "the most important surviving nineteenth-century industrial building in Detroit."

Machine Shop photo gallery

- Machine Shop, Contemporary and historical images

-

Machine shop in 1894.

-

Machine shop in 2009.

-

South side wall, 2009. Note construction date and remnants of "Detroit Shipbuilding Machine Shop" sign

-

Structure of a machine shop bay. Note steel framing structural elements framing the bay.

-

Interior of the machine shop in 1894

-

Interior of the machine shop c. 1915

-

Interior of the machine shop in 2002

-

Interior of the machine shop in 2009

-

Gallery in the machine shop, 1894

Industrial Loft Building and Foundry (1902)

In 1902, the company constructed two structures: the Industrial Loft Building and a foundry. The Industrial Loft Building ran along Atwater from the east side of the machine shop to what was then Dequindre. The loft building fronted on Atwood, stretching from the machine shop to Dequindre; the foundry faced Dequindre north of the loft building, completing the enclosure of the entire city block from Atwood to Guoin and Orleans to Dequindre.

Foundry

The foundry is 151 feet (46 m) long and 75 feet (23 m) wide, and stands 50 feet (15 m) high to the top of the wall; a roof monitor adds another 14 feet (4.3 m) to the height. The building is divided into seven 21-foot-wide bays (6.4 m). Clerestory windows run the length of the building. The interior is sectioned into a 46-foot-wide (14 m) main section and a 26-foot-wide lean-to (7.9 m).

Like the machine shop, the foundry is constructed with a load-bearing steel frame sheathed with non-load-bearing brick. The interior bays ran the full height of the building to make room for an overhead crane.

The foundry building operated as a foundry for only a little over a decade. Sometime in the 1910s, the company built a new foundry and this building was converted into an erecting shop. At some time afterward, possibly as late as the 1950s, the southernmost bay of the building was turned into a loading dock with the addition of an interior concrete block wall. Balconies above the dock were constructed, likely for storage.

Industrial Loft Building

At the same time as the foundry was constructed, the Detroit Shipbuilding Company also built a three-story loft building. The loft building fronted on Atwater Street, and was 172 feet (52 m) long, 50 feet (15 m) wide, and 55 feet (17 m) high to the top of the roof pediment.

The building was originally occupied by a blacksmith's shop, bolt-cutter, and office space on the first floor, a pattern shop and tool room on the second floor, and engineering offices and storage on the third floor. In addition, two narrow drives passed through the first floor to an interior courtyard. These drives were later bricked in. Other alterations of the facade over time include bricking in of windows on the east side and the addition of doors on the south side.

Like the machine shop and foundry, the loft building had a steel-framed structure with brick curtain walls. The framing supported the loads on the floors as well as the weight of the roof. The steel framing, however, was wholly contained within the building rather than being encased in the brick.

- Foundry and Industrial Loft Building Interiors

-

Interior of foundry, 2002.

-

Interior of foundry, 2009, looking west. Note interior passageway stretching through the complex to the machine shop.

-

Interior of Industrial Loft Building, 2002, first floor.

-

Interior of Industrial Loft Building, 2002, second floor.

Machine shop addition, chipping room, and shipping/receiving (c. 1910s)

Sometime between 1910 and 1919, three more structures were built, enclosing the yard between the 1892 machine shop and the 1902 foundry.

Machine shop addition

The machine shop addition is a steel-framed structure 122 feet (37 m) long, 41 feet (12 m) wide, and 43 feet (13 m) high to the roof trusses. A roof monitor extended the height another 4 feet (1.2 m). It was built along the east side of the 1892 machine shop; the brick in-fill of the machine shop was removed to provide a continuous inner area. The north wall of the structure had a large steel-framed window wall, although the lower portion of it is now bricked in.

The interior of the addition was originally a wide, open space with an overhead crane similar to the one in the original machine shop. However, some time after 1922 a wooden floor was constructed within the building to provide a second story on top of a 22-foot-high (6.7 m) first-floor bay.

Chipping room

Some time later, a chipping room was built along the north end of the block between the machine shop addition and the foundry building, displacing remnants of earlier buildings in the same place. The chipping room was where surface imperfections of castings were removed. This structure is also steel-framed, sharing its columns with adjacent buildings on the east and west. The building is 80 feet (24 m) long and 56 feet (17 m) wide, and was built in two sections separated by a masonry wall. Much of the north side was originally steel-framed windows; these have since been covered with blocks.

Shipping/receiving

In 1918, the company constructed a shipping/receiving building in the center of the complex, within what was previously an interior courtyard. This structure is a two-story steel-framed building measuring 5 by 72 feet (1.5 m × 22 m). The first floor was originally a shipping/receiving area, with access to Atwater via the drives running through the industrial loft building. The second floor functioned as a stockroom. A roof monitor provided light for the second floor, but the completely encased first floor required artificial lighting.

References

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- ^ Jeff Waraniak (December 28, 2015). "Enjoy the Great Indoors at the DNR's Outdoor Adventure Center". Hour Magazine.

- ^ Thomas A. Klug, Archived July 13, 2007, at the Wayback Machine Historic American Engineering Record: Dry Dock Engine Works, HAER no. MI-330, 2002, p. 1

- ^ Betsy H. Bradley, The works: the industrial architecture of the United States, 1999, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-509000-4 p. 149-150

- ^ Klug, p. 22

- ^ Detroit Dry Dock Company/Globe Trading Building from Detroit1701.org, retrieved 9/16/09

- ^ Klug, p.13

- ^ Klug, p. 5

- ^ Klug, p. 7

- ^ Klug, p. 8

- ^ Klug, p. 43

- ^ Klug, p. 11

- ^ Klug, p. 16

- ^ Klug, p. 14

- ^ Klug, p. 15

- ^ Klug, p. 20

- ^ Klug, p. 21

- ^ John Gallagher, "RIVERFRONT DEVELOPMENT: Back in the building: Historic structure to become living space." Detroit Free Press, October 20, 2006. Retrieved September 19, 2009

- ^ "EPA awards Brownfields grants to 16 Michigan communities and organizations," 05/14/2007, from the EPA

- ^ Daniel Duggan And Sherri Begin Welch, "Waterfront improvements aim to spur private development," Crain's Detroit Business, Aug. 23, 2009

- ^ Olga Stella, "Preservation for Economic Development," at Model D Detroit, retrieved 9/19/09

- ^ Sketch made using diagram contained in Thomas A. Klug, Historic American Engineering Record: Dry Dock Engine Works, HAER no. MI-330, 2002

- ^ Klug, p. 24

- ^ Detroit Dry Dock Company, Around the Lakes: Containing a Full List of American Lake Vessels, and Addresses of Managing Owners, Condensed Statistics of the Lake Business, and a Historical Resume and Illustrations of the Plant, and Vessels Built by the Detroit Dry Dock Company, Detroit, Mich. ship and Engine Builders, Marine Review Print., Cleveland, 1894, p. 115.

- ^ Klug, p. 40

- ^ Klug, p. 30

- ^ Klug, p. 33

- ^ Klug, p. 36

- ^ Klug, p. 37

- ^ Klug, p. 35

- ^ Klug, p. 26

- ^ Around the Lakes p. 86.

- ^ Klug, p. 27

- ^ Klug, p. 49

- ^ Eric J. Hill, John Gallagher AIA Detroit: the American Institute of Architects guide to Detroit architecture, 2003, Wayne State University Press, ISBN 0-8143-3120-3, p. 229

- ^ Klug, p. 44

- ^ Klug, p. 46

- ^ Klug, p. 45

- ^ Klug, p. 47

- ^ Klug, p. 48

External links

- Outdoor Adventure Center

- Detroit Dry Dock Company, Around the Lakes: Containing a Full List of American Lake Vessels, and Addresses of Managing Owners, Condensed Statistics of the Lake Business, and a Historical Resume and Illustrations of the Plant, and Vessels Built by the Detroit Dry Dock Company, Detroit, Mich. ship and Engine Builders, Marine Review Print., Cleveland, 1894.

- Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) No. MI-330, "Dry Dock Engine Works, 1801 Atwater Street, Detroit, Wayne County, MI", 28 photos, 20 measured drawings, 60 data pages, 3 photo caption pages

- Berlin Iron Bridge Company Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine history

- Video of the structure

- Inside the abandoned Dry Dock Complex

- Detroit Dry Dock complex photos by Kathy Toth

![Steamer EC Pope in Detroit Dry Dock No 2, c. 1894. Note machine shop in left background and Dry Dock Hotel in right background.[5]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5c/Steamer_EC_Pope_in_Detroit_Dry_Dock_No_2.jpg/156px-Steamer_EC_Pope_in_Detroit_Dry_Dock_No_2.jpg)