Duwamish Waterway

Name

In the Lushootseed language, the name of the Duwamish River (and of the Cedar River) is dxʷdəw, meaning "inside." The Lushootseed name for the Duwamish people, who lived along the river and its tributaries, is dxʷdəwʔabš, meaning "people of the inside."

History

For thousands of years, the Duwamish people have lived along the Duwamish River and its tributaries. The earliest archaeological evidence of human habitation along the Duwamish River dates back to the 6th century CE. The Duwamish traditionally used the river to hunt ducks and geese, fish for salmon, cod, and halibut, harvest clams, and gather berries, camas, and other plants for food and medicinal purposes. When the first American settlers came to what is now the Seattle area in 1851, the Duwamish lived in more than 90 longhouses, in at least 17 villages.

Native villages on the Duwamish were eventually supplanted by white settlements and commercial uses, and there was evidence of deliberate burning of Indian longhouses in 1893. Duwamish people continued to work and fish in the area, using man-made "Ballast Island" on the Seattle waterfront as a canoe haul-out and informal market, but by the early 20th Century, most remnants of traditional life along the river had disappeared.

Until 1906, the White and Green Rivers combined at Auburn, and joined the Black River at Tukwila to form the Duwamish. In 1906, however, the White River changed course following a major flood and emptied into the Puyallup River as it does today. The lower portion of the historic White River—from the historic confluence of the White and Green Rivers to the confluence with the Black River—is now considered part of the Green River. Later, in 1911 the Cedar River was diverted to empty into Lake Washington instead of into the Black River; at that time, the lake itself still emptied into the Black River. Then, with the opening of the Lake Washington Ship Canal in 1916, the lake's level dropped nearly nine feet and the Black River dried up. From that time forward, the point of the name change from Green to Duwamish is no longer the confluence of the Green and Black Rivers, though it has not changed location.

The last year-round Duwamish residents on the river – an old man named Seetoowathl, and his wife – died of starvation in their float-house on Kellogg Island in the winter of 1920.

In 2009, the Duwamish Longhouse and Cultural Center was opened on the west bank of the river as part of the Duwamish Tribal Organization's reassertion of its historic rights in the area and its continuing struggle for federal recognition as the Duwamish Tribe.

Duwamish Waterway

As of the present day, the Duwamish Waterway empties into Elliott Bay in Seattle. The waterway was completed after the completion of the man-made Harbor Island in 1909. The waterway is now divided into two channels, the East and West Waterways.

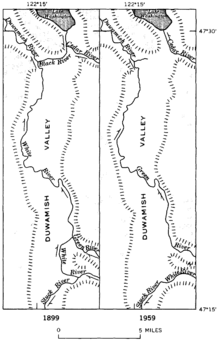

In 1895, Eugene Semple, who had earlier served as Governor of Washington Territory, outlined a plan for a series of major public works projects in the Seattle area, including the straightening and dredging of the Duwamish River, both to open up the area to commercial use and to alleviate flooding. In 1909 the City of Seattle formed the Duwamish Waterway Commission to sell bonds and oversee the re-channelling of the river. Work began in October 1913, and the oxbows gradually disappeared, with a few recesses in the channel left to accommodate high water flows and turning ships. Parts of the Georgetown and South Park neighborhoods once on quiet riverbank found themselves inland; the Georgetown Steam Plant was now almost a mile from the river, and special water pumping facilities had to be installed. By 1920, 4½ miles of the Duwamish Waterway had been dredged to a depth of 50 feet, with 20 million cubic feet of mud and sand going into the expansion of Harbor Island. The shallow, meandering, nine-mile-long river became a five-mile engineered waterway capable of handling ocean-going vessels.

The Duwamish basin soon became Seattle's industrial and commercial core area. Activities included cargo handling and storage, marine construction, ship and boat manufacturing, concrete manufacturing, paper and metals fabrication, food processing, and countless other industrial operations. Boeing Plant 1 was established on the Lower Duwamish in 1916, and Boeing Plant 2, further upriver, in 1936.

Pollution

Due to 20th century industrial contamination, the lower 5 miles (8.0 km) of the Duwamish Waterway was declared a Superfund site by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 2001. The contaminants include PCBs, PAHs, arsenic, mercury, and phthalates, discharged from multiple industries.

The cleanup included a plan for an "early action" or hotspot cleanup proposed to dredge contaminated sediment and dump the resulting sludge in Tacoma's Commencement Bay, 26 miles (42 km) to the southwest. Opposition to this plan in both Seattle and Tacoma forced the sludge to be shipped to Klickitat County in south central Washington instead of disposal in Puget Sound. EPA has identified responsible parties for the pollution and in 2014 it published a final cleanup plan. By late 2015, 50 percent of the PCB-contaminated sediment had been removed. As of 2022, cleanup and restoration efforts are ongoing.

The Duwamish River faces other types of pollution such as fecal coliform bacteria, caused by combined sewer overflows. If these overflows were to be cleaned up, the overall quality of the water would not improve much. The river's most common pollutant is petroleum. Other common contamination occurs from farms, surface runoff, or failing septic tanks.

With the spread of ecological concerns in the 1970s, various environmental, tribal, and community organizations became interested in the severely polluted Duwamish River and Waterway. Kellogg Island, the last remnant of the original river, was declared a wildlife preserve, and nearby terminal T-107 was converted into a park, creating a substantial natural area near the mouth of the river. In 2001, the Duwamish River Cleanup Coalition (DRCC) was established as a community advisory group in response to the EPA declaring the Duwamish a Superfund site. As of 2023, the DRCC continues to organize cleanup events, provide community education, and campaign for environmental justice.

Wildlife

Despite the industrialization of the Duwamish river, it remains an important habitat for the wildlife in the area. Thousands of salmon and trout that visit the marshes and estuaries each year to spawn. The Duwamish supports chinook, coho, chum and steelhead, as well as the more rare sockeye, sea-run cutthroat trout and bull trout. Pink salmon run in the millions every odd-numbered years in recent history. Canada geese, great blue herons, starlings, cormorants, pigeons, buffleheads, Caspian terns, warblers, hawks, ospreys, bald eagles, and numerous waterfowl call the river home and can be seen feeding in and around its waters.

Many of the animal species found in or around the river contain an unhealthy amount of contaminants. For example, other than salmon, any type of fish or shellfish found in the river is unfit for human consumption. It was found that PCB levels in fish and crab that live in the waterway most of their lives are 35 to 110 times higher than in Puget Sound salmon. The Ecological Risk Assessment also found that river otters from the Lower Duwamish River might be exposed to such high levels of PCBs that the growth or survival of their offspring may be reduced.

Recreation

The Port of Seattle owns several properties along the Duwamish River and industrial channels. In 2020, a set of six parks were renamed to use Indigenous Lushootseed names following consultation with local tribes.

Bridges

The Duwamish Waterway is spanned by four major, public bridges: the First Avenue South Bridge, the South Park Bridge, the Spokane Street Bridge, and, directly above the latter, the West Seattle Bridge. Historically, the West Spokane Street Bridge also crossed the west fork of the Duwamish Waterway from 1924 until the 1970s and 1980s.

See also

References

- ^ Bates, Dawn; Hess, Thom; Hilbert, Vi (1994). Lushootseed Dictionary. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-97323-4. OCLC 29877333.

- ^ "Culture and History". Duwamish Tribe. Archived from the original on January 20, 2018. Retrieved December 11, 2023.

- ^ "Seattle's Duwamish Tribe celebrates new Longhouse and Cultural Center on January 3, 2009. - HistoryLink.org". www.historylink.org. Retrieved December 11, 2023.

- ^ Duwamish Tribe-Exile to Ballast Island; http://www.duwamishtribe.org/ballastisland.html Archived November 27, 2015, at the Wayback Machine retvd 12 13 15

- ^ "The Green-Duwamish: A River System Re-Plumbed", The Green-Duwamish River: Connecting people with a diverse environment. Duwamish River Cleanup Coalition/TAG. No date, appears to be 2008 or 2009.

- ^ Gwinn, Mary Ann-"Native landscape: The rich layer of indigenous history under Seattle's skin",The Seattle Times, August 30, 2007

- ^ "Waterlines: Overview". www.burkemuseum.org. Retrieved December 11, 2023.

- ^ Wilma, David-"Straightening of Duwamish River begins on October 14, 1913." HistoryLink.org Essay 2986; http://www.historylink.org/index.cfm?DisplayPage=output.cfm&File_Id=2986 retvd 12 13 15

- ^ Boeing-History of the Duwamish Waterway; http://www.boeing.com/principles/environment/duwamish/history.page retvd 12 13 15

- ^ "Lower Duwamish Waterway; Cleanup Activities". Superfund. Seattle, WA: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). July 15, 2022.

- ^ "Lower Duwamish Waterway; Health & Environment". Superfund. EPA. July 15, 2022.

- ^ Paulson, Tom (September 11, 2003). "Tainted sludge won't go to Tacoma". Seattle Post-Intelligencer.

- ^ Impacts of Environmental Problems on the Reuse and Redevelopment of the Properties in the Duwamish Industrial Area (Report). Seattle, WA: Remediation Technologies, Inc. 1994.

- ^ Combined Sewer Overflow Water Quality Assessment for the Duwamish River and Elliott Bay; Stakeholder Committee Report (Report). Seattle, WA: King County Department of Natural Resources. 1999.

- ^ "$4.6 Million Project Will Restore 16.5 Acres of Critical Aquatic Habitat Along Lower Duwamish River at Seaboard Lumber Site". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. November 3, 1998. Press release. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016.

- ^ "How EPA wants to spend $290M to clean up a Superfund site in Seattle". The Seattle Times. May 1, 2023. Retrieved November 6, 2023.

- ^ "Seattle's Aquatic Environments: Duwamish Estuary" (PDF). City of Seattle. Retrieved April 4, 2009.

- ^ "Duwamish Waterway Park, King County, WA, US – eBird Hotspot". ebird.org. Retrieved December 30, 2022.

- ^ "Lower Duwamish Waterway Superfund Site" (PDF). Region 10 Cleanup. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. June 2008. Retrieved November 3, 2008.

- ^ "Port Announces New Names for Six Parks along the Duwamish River" (Press release). Port of Seattle. October 27, 2020. Retrieved December 14, 2021.

External links

- Partnow, Jessica (September 24–28, 2007). "Life on the Duwamish:Rediscovering Seattle's Dirty South". KUOW-FM. Archived from the original on October 17, 2015. Retrieved September 3, 2014.

- McClure, Robert (November 26–28, 2007). "A River Lost? Decision time on the Duwamish". The Seattle Post-Intelligencer.

- Three of a long series published by the Seattle Post-Intelligencer in Nov–Dec 2007.

- River Lost?, November 11, 2007.

- Many question if Seattle's Duwamish waterway can ever be restored, November 25, 2007.

- River: Dead or alive?, December 1, 2007.