Explicit Material

The oldest artifacts considered pornographic were discovered in Germany in 2008 and are dated to be at least 35,000 years old. Human enchantment with sexual imagery representations has been a constant throughout history. However, the reception of such imagery varied according to the historical, cultural, and national contexts. The Indian Sanskrit text Kama Sutra (3rd century CE) contained prose, poetry, and illustrations regarding sexual behavior, and the book was celebrated; while the British English text Fanny Hill (1748), considered "the first original English prose pornography," has been one of the most prosecuted and banned books. In the late 19th century, a film by Thomas Edison that depicted a kiss was denounced as obscene in the United States, whereas Eugène Pirou's 1896 film Bedtime for the Bride was received very favorably in France. Starting from the mid-twentieth century on, societal attitudes towards sexuality became lenient in the Western world where legal definitions of obscenity were made limited. In 1969, Blue Movie by Andy Warhol became the first film to depict unsimulated sex that received a wide theatrical release in the United States. This was followed by the "Golden Age of Porn" (1969–1984). The introduction of home video and the World Wide Web in the late 20th century led to global growth in the pornography business. Beginning in the 21st century, greater access to the Internet and affordable smartphones made pornography more mainstream.

Pornography has been vouched to provision a safe outlet for sexual desires that may not be satisfied within relationships and be a facilitator of sexual fulfillment in people who do not have a partner. Pornography consumption is found to induce psychological moods and emotions similar to those evoked during sexual intercourse and casual sex. Pornography usage is considered a widespread recreational activity in-line with other digitally mediated activities such as use of social media or video games. People who regard porn as sex education material were identified as more likely not to use condoms in their own sex life, thereby assuming a higher risk of contracting sexually transmitted infections (STIs); performers working for pornographic studios undergo regular testing for STIs unlike much of the general public. Comparative studies indicate higher tolerance and consumption of pornography among adults tends to be associated with their greater support for gender equality. Among feminist groups, some seek to abolish pornography believing it to be harmful, while others oppose censorship efforts insisting it is benign. A longitudinal study ascertained that pornography use is not a predictive factor in intimate partner violence. Porn Studies, started in 2014, is the first international peer-reviewed, academic journal dedicated to the critical study of "products and services" deemed pornographic.

Pornography is a major influencer of people's perception of sex in the digital age; numerous pornographic websites rank among the top 50 most visited websites worldwide. Called an "erotic engine", pornography has been noted for its key role in the development of various communication and media processing technologies. For being an early adopter of innovations and a provider of financial capital, the pornography industry has been cited to be a contributing factor in the adoption and popularization of media related technologies. The exact economic size of the porn industry in the early twenty-first century is unknown. In 2023, estimates of the total market value stood at over US$172 billion. The legality of pornography varies across countries. From the mid-2010s, unscrupulous pornography such as deepfake pornography and revenge porn have become issues of concern.

Etymology and definition

The word pornography is a conglomerate of two ancient Greek words: πόρνος (pórnos) "fornicators", and γράφειν (gráphein) "writing, recording, or description". In Greek language, the term pornography connotes depiction of sexual activity; no date is known for the first use of the term pornography, the earliest attested, most related word found is πορνογράφος (pornographos) i.e. "someone writing about harlots" in the 3rd century CE work Deipnosophists by Athenaeus.

The oldest published reference to the word pornography as in 'new pornographie,' is dated back to 1638 and is credited to Nathaniel Butter in a history of the Fleet newspaper industry. The modern word pornography entered the English language as the more familiar word in 1842 via French "pornographie," from Greek "pornographos".

The term porn is an abbreviation of pornography. The related term πόρνη (pórnē) "prostitute" in Greek, originally meant "bought, purchased" similar to pernanai "to sell", from the proto-Indo-European root per-, "to hand over" — alluding to act of selling.

The word pornography was originally used by classical scholars as "a bookish, and therefore inoffensive term for writing about prostitutes", but its meaning was quickly expanded to include all forms of "objectionable or obscene material in art and literature". In 1864, Webster's Dictionary published "a licentious painting" as the meaning for pornography, and the Oxford English Dictionary: "obscene painting" (1842), "description of obscene matters, obscene publication" (1977 or earlier).

Definitions for the term "pornography" are varied, with people from both pro- and anti-pornography groups defining it either favorably or unfavorably, thus making any definition very stipulative. Nevertheless, academic researchers have defined pornography as sexual subject material such as a picture, video, text, or audio that is primarily intended to assist sexual arousal in the consumer, and is created and commercialized with "the consent of all persons involved". Arousal is considered the primary objective, the raison d'etre a material must fulfill for it to be treated as pornographic. As some people can feel aroused by an image that is not meant for sexual arousal and conversely cannot feel aroused by material that is clearly intended for arousal, the material that can be considered as pornography becomes subjective.

Pornography throughout history

Pornography from ancient times

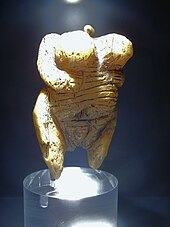

Pornography is viewed by historians as a complex cultural formation. Depictions of a sexual nature existed since prehistoric times as seen in Venus figurines and rock art. People across various civilizations created works that depicted explicit sex; these include artifacts, music, poetry, and murals among other things that are often intertwined with religious and supernatural themes. The oldest artifacts, including the Venus of Hohle Fels, which is considered to be borderline pornographic, were discovered in 2008 CE at a cave near Stuttgart in Germany, radiocarbon dating suggests they are at least 35,000 years old, from the Aurignacian period.

Vast number of artifacts discovered in ancient Mesopotamia region had explicit depictions of heterosexual sex. Glyptic art from the Sumerian Early Dynastic Period frequently showed scenes of frontal sex in the missionary position. In Mesopotamian votive plaques from the early second millennium (c. 2000 – c. 1500 BCE), a man is usually shown penetrating a woman from behind while she bends over drinking beer through a straw. Middle Assyrian lead votive figurines often portrayed a man standing and penetrating a woman as she rests on an altar. Scholars have traditionally interpreted all these depictions as scenes of hieros gamos (an ancient sacred marriage between a god and a goddess), but they are more likely to be associated with Inanna, the Mesopotamian goddess of sex and sacred prostitution. Many sexually explicit images, including models of male and female sexual organs were found in the temple of Inanna at Assur.

Depictions of sexual intercourse were not part of the general repertory of ancient Egyptian formal art, but rudimentary sketches of heterosexual intercourse have been found on pottery fragments and in graffiti. The final two thirds of the Turin Erotic Papyrus (Papyrus 55001), an Egyptian papyrus scroll discovered at Deir el-Medina, consists of a series of twelve vignettes showing men and women in various sexual positions. The scroll was probably painted in the Ramesside period (1292–1075 BCE) and its high artistic quality indicates that it was produced for a wealthy audience. No other similar scrolls have yet been discovered.

Archaeologist Nikolaos Stampolidis had noted that the society of ancient Greece held lenient attitudes towards sexual representation in the fields of art and literature. The Greek poet Sappho's Ode to Aphrodite (600 BCE) is considered an earliest example of lesbian poetry. Red-figure pottery invented in Greece (530 BCE) often portrayed images that displayed eroticism. The fifth-century BC comic Aristophanes elaborated 106 ways of describing the male genitalia and in 91 ways the female genitalia. Lysistrata (411 BCE) is a sex-war comedy play performed in ancient Greece.

In India, Hinduism embraced an inquisitive attitude towards sex as an art and a spiritual ideal. Some ancient Hindu temples incorporated various aspects of sexuality into their art work. The temples at Khajuraho and Konark are particularly renowned for their sculptures, which had detailed representations of human sexual activity. These depictions were viewed with a spiritual outlook as sexual arousal is believed to indicate the embodying of the divine.

"pornography is sometimes characterised as the symptom of a degenerate society, but anyone even noddingly familiar with Greek vases or statues on ancient Hindu temples will know that so-called unnatural sex acts, orgies and all manner of complex liaisons have for millennia past been represented in art for the pleasure and inspiration of the viewer everywhere. The desire to ponder images of love-making is clearly innate in the human – perhaps particularly the male – psyche." — Tom Hodgkinson

Kama, the word used to connote sexual desire, was explored in Indian literary works such as the Kama Sutra, which dealt with the practical as well as the psychological aspects of human courtship and sexual intercourse. The Sanskrit text Kama sutra was compiled by the sage Vatsyayana into its final form sometime during the second half of the third century CE. This text, which included prose, poetry, as well as illustrations regarding erotic love and sexual behavior, is one of the most celebrated Indian erotic works. Koka shastra is another medieval Indian work that explored kama.

Pornography from the Roman era

When large-scale archaeological excavations were undertaken in the ancient Roman city of Pompeii during the 18th century, much of the erotic art in Pompeii and Herculaneum came to light, shocking the authorities who endeavored to hide them away from the general public. In 1821, the moveable objects were locked away in the Secret Museum in Naples, and what could not be removed was either covered or cordoned off from public view.

Other examples of early art and literature of sexual nature include: Ars Amatoria (Art of Love), a second-century CE treatise on the art of seduction and sensuality by the Roman poet Ovid; the artifacts of the Moche people in Peru (100 CE to 800 CE); The Decameron, a collection of short stories, some of which are sexual in nature by the 14th-century Italian author Giovanni Boccaccio; and the fifteenth-century Arabic sex manual The Perfumed Garden.

Pornography from early modern era

A highly developed culture of visual erotica flourished in Japan during the early modern era. From at least the 17th century, erotic artworks became part of the mainstream social culture. Depictions of sexual intercourse were often presented on pictures that were meant to provide sex education for medical professionals, courtesans, and married couples. Makura-e (pillow pictures) were made for entertainment as well as for the guidance of married couples. The ninth-century Japanese art form "Shunga", which depicted sexual acts on woodblock prints and paintings became so popular by the 18th century that the Japanese government began to issue official edicts against them. Even so, Japanese erotica flourished with the works of artists such as Suzuki Harunobu achieving worldwide fame. Japanese censorship laws enacted in 1870 made the production of erotic works difficult. The laws remained in effect until the end of the Pacific War in 1945; nevertheless, pornography flourished through the sale of "erotic, grotesque, nonsense" (ero-guro-nansensu) periodicals, particularly in the Taishō era (1912–1926). From the 1960s, pink films, which portrayed sexual themes became popular in Japan. In 1981 the first Japanese Adult video (AV) was released. The Japanese pornography industry peaked in the early 2000s when about 30,000 AVs were made a year. From the mid-2010s, increased availability of free porn on the Internet led to a decline in the production of AVs. Other forms of adult entertainment such as hentai, which refers to pornographic manga and anime, and erotic video games have become popular in recent decades.

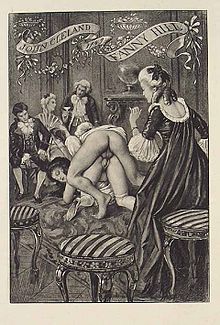

In Europe, the Italian Renaissance work from the 16th century - I Modi (The Ways) also known as The Sixteen Pleasures became famous for its engravings that explicitly depicted sex positions. The publication of this book was considered the beginning of print pornography in Rome. The second edition of this book was published in 1527, titled Aretino Postures, which combined erotic images with text - a first in the Western culture. The Vatican called for the complete destruction of all the copies of the book and imprisonment of its author Marcantonio Raimondi. With the development of printing press in Europe, the publication of written and visual material, which was essentially pornographic began. Heptaméron written in French by Marguerite de Navarre and published posthumously in 1558 is one of the earliest examples of salacious texts from this era. Beginning with the Age of Enlightenment and advances in printing technology, the production of erotic material became popular enough that an underground marketplace for such works developed in England with a separate publishing and bookselling business. Historians have identified the 18th century as an age of pornographic opulence. Written by anonymous authors, the titles: The Progress of Nature (1744); The History of the Human Heart: or, the Adventures of a Young Gentleman (1749), which had descriptions of female ejaculation; and The Child of Nature (1774) have been noted as prominent pornographic fictional works from this period. The book Fanny Hill (1748), is considered "the first original English prose pornography, and the first pornography to use the form of the novel." An erotic literary work by John Cleland, Fanny Hill was first published in England as Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure. The novel has been one of the most prosecuted and banned books in history. The author John Cleland was charged for "corrupting the King's subjects."

At around the same time, erotic graphic art that began to be extensively produced in Paris came to be known in the Anglosphere as "French postcards". Enlightenment-era France had been noted by historians as the center of origin for modern-era pornography. The works of French pornography, which often concentrated on the education of an ingénue into libertine, dominated the sale of sexually explicit content. The French sought to interlace narratives of sexual pleasure with philosophical and anti-establishment basis. Political pornography began with the French Revolution (1789–99). Apart from the sexual component, pornography became a popular medium for protest against the social and political norms of the time. Pornography during this period was used to explore the ideas of sexual freedom for women and men, the various methods of contraception, and to expose the offenses of powerful royals and elites. The working and lower classes in France produced pornographic material en masse with themes of impotency, incest, and orgies that ridiculed the authority of the Church-State, aristocrats, priests, monks, and other royalty.

One of the most important authors of socially radical pornography was the French aristocrat Marquis de Sade (1740–1814), whose name helped derive the words "sadism" and "sadist". He advocated libertine sexuality and published writings that were critical of authorities, many of which contained pornographic content. His work Justine (1791) interlaced orgiastic scenes along with extensive debates on the ills of property and traditional hierarchy in society.

Pornography in the Victorian era

During the Victorian era (1837–1901), the invention of the rotary printing press made publication of books easier, many works of lascivious nature were published during this period often under pen names or anonymity. In 1837, the Holywell Street (known as "Booksellers' Row") in London had more than 50 shops that sold pornographic material. Many of the works published in the Victorian era are considered bold and graphic even by today's lenient standards. The English novel The Adventures, Intrigues, and Amours, of a Lady's Maid! written by anonymous "Herself" (c. 1838) professed the notion that homosexual acts are more pleasurable for women than heterosexuality which is linked to painful and uncomfortable experiences. Some of the popular publications from this era include: The Pearl (magazine of erotic tales and poems published from 1879 to 1881); Gamiani, or Two Nights of Excess (1870) by Alfred de Musset; and Venus in Furs (1870) by Leopold von Sacher-Masoch, from whose name the term "masochism" was derived. The Sins of the Cities of the Plain (1881) is one of the first sole male homosexual literary work published in English, this work is said to have inspired another gay literary work Teleny, or The Reverse of the Medal (1893), whose authorship has often been attributed to Oscar Wilde. The Romance of Lust, written anonymously and published in four volumes during 1873–1876, contained graphical descriptions of themes detailing incest, homosexuality, and orgies. Other publications from the Victorian era that included fetish and taboo themes such as sadomasochism and 'cross-generational sex' are: My Secret Life (1888–1894) and Forbidden Fruit (1898). On accusations of obscenity many of these works had been outlawed until the 1960s.

Criminalization

The English act

The world's first law that criminalized pornography was the English Obscene Publications Act 1857, enacted at the urging of the Society for the Suppression of Vice. The act passed by the British Parliament in 1857 applied to the United Kingdom and Ireland. The act made the sale of obscene material a statutory offense, and gave the authorities the power to seize and destroy any material which they considered as obscene.

For centuries before, sexually explicit material was considered a domain that is exclusive to aristocratic classes. When pornographic material flourished in the Victorian-era England, the affluent classes believed they are sensible enough to deal with it, unlike the lower working classes whom they thought would get distracted by such material and cease to be productive. Beliefs that masturbation would make people ill, insane, or become blind also flourished. The obscenity act gave government officials the power to interfere in the private lives of people unlike any other law before. Some of the people suspected for masturbation were forced to wear chastity devices. "Cures" and "treatment" for masturbation involved such measures like giving electric shock and applying carbolic acid to the clitoris. The law was criticized for being established on still yet unproven claims that sexual material is noxious for people or public health.

The American act

In 1865, the US postal service was seen as a "vehicle" for the transmission of materials that were deemed obscene by the American lawmakers. An act relating to the postal services was passed, which made people pay a fine of $500 for knowingly mailing any "obscene book, pamphlet, picture print, or other publication". From 1865 to up until the first three months of 1872, a total number of nine people were held for various charges of obscenity, with one person sentenced to prison for a year; while in the next ten months fifteen people were arrested under this law. This was partly due to the efforts of Anthony Comstock, who became a major figure in 1872 and held great power to control sexual related activities of people including the choice of abortion. The Comstock Act of 1873 is the American equivalent of the English Obscene Act. The anti-obscenity bill, drafted by Anthony Comstock, was debated for less than an hour in the US Congress before being passed into law. Apart from the power to seize and destroy any material alleged to be obscene, the law made it possible for the authorities to make arrests over any perceived act of obscenity, which included possession of contraceptives by married couples. Reportedly in the US, 15 tons of books and 4 million pictures were destroyed, and about 15 people were driven to suicide with 4,000 arrests. At least 55 people whom Comstock identified as abortionists got indicted under the Comstock act.

Steps towards liberalization

The laws regarding pornography have differed in various historical, cultural, and national contexts. The English Act did not apply to Scotland where the common law continued to apply. Before the English Act, publication of obscene material was treated as a common law misdemeanor, this made effectively prosecuting authors and publishers difficult even in cases where the material was clearly intended as pornography. However, neither the English, nor the United States Act defined what constituted "obscene", leaving this for the courts to determine. For implementing the Comstock act, the US courts used the British Hicklin test to define obscenity, the definition of which was first proposed in 1868, ten years after the passing of the English obscene act. The definition became cemented in 1896 and continued until the mid-twentieth century. Starting from 1957 to 1997, the US Supreme Court made numerous judgments that redefined obscenity.

The nineteenth-century legislation eventually outlawed the publication, retail and trafficking of certain writings and images that were deemed pornographic. Although laws ordered the destruction of shop and warehouse stock meant for sale, the private possession and viewing of (some forms of) pornography was not made an offense until the twentieth century. Historians have explored the role of pornography in determining social norms. The Victorian attitude that pornography was only for a select few is seen in the wording of the Hicklin test, stemming from a court case in 1868, where it asked: "whether the tendency of the matter charged as obscenity is to deprave and corrupt those whose minds are open to such immoral influences".

Although officially prohibited, the sale of sexual material nevertheless continued through "under the counter" means. Magazines specialising in a genre called "saucy and spicy" became popular during this time (1896 to 1955), titles of few popular magazines include; Wink: A Whirl of Girls, Flirt: A FRESH Magazine, and Snappy. Cover stories in these magazines featured segments such as "perky pin-ups" and "high-heel cuties". Some of the popular erotic literary works from the twentieth century include the novels: Story of the Eye (1928), Tropic of Cancer (1934), Tropic of Capricorn (1938), the French Histoire d'O (Story of O) (1954); and the short stories: Delta of Venus (1977), and Little Birds (1979).

Invention of photography and filmography

After the invention of photography, the birth of erotic photography followed. The oldest surviving image of a pornographic photo is dated back to about 1846, described as to depict "a rather solemn man gingerly inserting his penis into the vagina of an equally solemn and middle-aged woman". At one point of time, it was more expensive to purchase an erotic photograph than to hire a prostitute. The Parisian demimonde included Napoleon III's minister, Charles de Morny, an early patron who delighted in acquiring and displaying erotic photos at large gatherings.

Pornographic film production commenced almost immediately after the invention of the motion picture in 1895. A pioneer of the motion picture camera, Thomas Edison, released various films, including The Kiss that were denounced as obscene in late 19th century America. Two of the earliest pioneers of pornographic films were Eugène Pirou and Albert Kirchner. Kirchner directed the earliest surviving pornographic film for Pirou under the trade name "Léar". The 1896 film, Le Coucher de la Mariée, showed Louise Willy performing a striptease. Pirou's film inspired a genre of risqué French films that showed women disrobing, and other filmmakers realized profits could be made from such films.

Legalization

Sexually explicit films opened producers and distributors to be liable for prosecution. Such films were produced illicitly by amateurs, starting in the 1920s, primarily in France and the United States. Processing the film was risky as was their distribution, which was strictly private. In the Western world, during the 1960s, social attitudes towards sex and pornography slowly changed. In 1967, Denmark repealed the obscenity laws on literature; this led to a decline in the sale of pornographic and erotic literature. Hoping for a similar effect, in the summer of 1969, legislators in Denmark abolished censorship on picture pornography, thereby effectively becoming, from July 1, 1969, the first country that legalized pornography, including child pornography, which was later prohibited in 1980. The 1969 legislation, instead of resulting in a decline in pornography production, led to an explosion of investment in, and commercial production of pornography in Denmark, which made the country's name synonymous with sex and pornography. The total retail turnover of pornography in Denmark for the year 1969 was estimated at $50 million. Much of the pornographic material produced in Denmark was smuggled into other countries around the world.

In the United States, pornography is protected by the First Amendment to the United States Constitution unless it constitutes obscenity or child pornography that is produced with real children. Nevertheless, in Stanley v. Georgia (1969), the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the right of an adult to possess obscene material in private. Subsequently, however, the Supreme Court rejected the claim that under Stanley there is a constitutional right to provide obscene material for private use or to acquire it for private use. The right to possess obscene material does not imply the right to provide or acquire it, because the right to possess it "reflects no more than ... the law's 'solicitude to protect the privacies of the life within [the home]'".

In 1969, Blue Movie by Andy Warhol became the first feature film to depict explicit sexual intercourse that received a wide public theatrical release in the United States.

Blue Movie was real. But it wasn't done as pornography—it was done as an exercise, an experiment. But I really do think movies should arouse you, should get you excited about people, should be prurient. Prurience is part of the machine. It keeps you happy. It keeps you running."

Film scholar Linda Williams remarked that prurience "is a key term in any discussion of moving-image sex since the sixties. Often it is the "interest" to which no one wants to own up". In 1968, the Motion Picture Association of America created a new film ratings system in which any film that was not approved by the association was released with an "X" rating. When pornographers began to release their productions with the rating X, the association adopted NC-17 rating for adults only films, leaving the X rating to pornography. Later the invented gimmick rating "XXX" became a standard for pornographic material.

Commissions and their findings

In 1970, the United States President's Commission on Obscenity and Pornography, set up to study the effects of pornography, reported that there was "no evidence to date that exposure to explicit sexual materials plays a significant role in the causation of delinquent or criminal behavior among youths or adults". The report further recommended against placing any restriction on the access of pornography by adults and suggested that legislation "should not seek to interfere with the right of adults who wish to do so to read, obtain, or view explicit sexual materials". Regarding the notion that sexually explicit content is improper, the Commission found it "inappropriate to adjust the level of adult communication to that considered suitable for children". The Supreme Court supported this view.

In 1971, Sweden removed its obscenity clause. Further relaxation of legislations during the early 1970s in the US, West Germany and other countries led to rise in pornography production. The 1970s had been described by Linda Williams as 'the "Classical" Era of Theatrically Exhibited Porn', a time period now called the Golden Age of Porn.

In 1979, the British Committee on Obscenity and Film Censorship better known as the Williams Committee, formed to review the laws concerning obscenity reported that pornography could not be harmful and to think anything else is to see pornography "out of proportion". The committee declared that existing variety of laws in the field should be scrapped and so long as it is prohibited from children, adults should be free to consume pornography as they see fit.

The Meese Report in 1986 argued against loosening restrictions on pornography in the US. The report was criticized as biased, inaccurate, and not credible.

In 1988, the Supreme Court of California ruled in the People v. Freeman case that "filming sexual activity for sale" does not amount to procuring or prostitution and shall be given protection under the first amendment. This ruling effectively legalized the production of X-rated adult content in the Los Angeles county, which by 2005 had emerged as the largest center in the world for the production of pornographic films. Pornographic films appeared throughout the twentieth century. First as stag films (1900–1940s), then as porn loops or short films for peep shows (1960s), followed by as feature films for theatrical release in adult movie theaters (1970s), and as home videos (1980s).

Role of magazines in legalization

Pornographic magazines published during the mid-twentieth century have been noted for playing an important role in the sexual revolution and the liberalization of laws and attitudes towards sexual representation in the Western world. Hugh Hefner, in 1953 published the first US issue of the Playboy, a magazine which as Hefner described is a "handbook for the urban male". The magazine contained images of nude women along with articles and interviews covering politics and culture. Twelve years later, in 1965, Bob Guccione in the UK started his publication Penthouse, and published its first American issue in 1969 as a direct competitor to Playboy. In its early days, the images of naked women published in Playboy did not show any pubic hair or genitals. Penthouse became the first magazine to show pubic hair in 1970. Playboy followed the lead and there ensued a competition between the two magazines over publication of more racy pictures, a contest that eventually got labeled as the "Pubic Wars".

"We were the first to show full frontal nudity. The first to expose the clitoris completely. I think we made a very serious contribution to the liberalization of laws and attitudes. HBO would not have gone as far as it does if it was not for us breaking the barriers. Much that has happened now in the Western world with respect to sexual advances is directly due to steps that we took." — Bob Guccione, Penthouse founder in 2004.

The tussle between Playboy and Penthouse paled into obscurity when Larry Flynt started Hustler, which became the first magazine to publish labial "pink shots" in 1974. Hustler projected itself as the magazine for the working classes as opposed to the urban centered Playboy and Penthouse. During the same time in 1972, Helen Gurley Brown, editor of the Cosmopolitan magazine, published a centerfold that featured actor Burt Reynolds in nude. His popular pose has been later emulated by many other famous people. The success of Cosmo led to the launch of Playgirl in 1973. At their peak, Playboy sold close to six million copies a month in the US, while Penthouse nearly five million. In the 2010s, as the market for printed versions of pornographic magazines declined, with Playboy selling about a million and Penthouse about a hundred thousand, many magazines became online publications. As of 2005, the best-selling US adult magazines maintained greater reach compared to most other non-pornographic magazines, and often ranked among top-sellers.

Modern-day pornography

Modern-day pornography began to take shape from the mid-1980s when the first desktop computers and public computer networks were released. Since the 1990s, the Internet has made pornography more accessible and culturally visible. Before the 90s, Usenet newsgroups served as the base for what has been called the "amateur revolution" where non-professionals from the late 1980s and early 1990s, with the help of digital cameras and the Internet, created and distributed their own pornographic content independent of mainstream networks. The use of the World Wide Web became popular with the introduction of Netscape navigator in 1994. This development led to newer methods of pornography distribution and consumption. The Internet turned out to be a popular source for pornography and was called the "Triple A-Engine" for offering consumers "anonymity, affordability, and accessibility", while driving the business of pornography. The notion of Internet being a medium abound with porn became popular enough that in 1995 Time published a cover story titled "CYBERPORN" with the face of a shocked child as the cover photo. In the Reno v. ACLU (1997) ruling, the US Supreme Court upheld the legality of pornography distribution and consumption by adults over the Internet. The Court noted that government may not reduce the communication between adults to "only what is fit for children".

With the introduction of broadband connections, much of the distribution networks of pornography moved online giving consumers anonymous access to a wide range of pornographic material. To have better control over their content on the Internet some professional pornographers maintain their own websites. Danni's Hard Drive started in 1995 by Danni Ashe is considered one of the earliest online pornographic websites, coded by Ashe – a former stripper and nude model, the website was reported by CNN to had generated revenues of $6.5 million by 2000. According to some leading pornography providers on the Internet, customer subscription rates for a website would be about one in a thousand people who visit the site for a monthly fees averaging around $20. Ashe said in an interview that her website employs 45 people and she expects to earn $8 million in 2001 alone. The total number of pornographic websites in 2000 were estimated to be more than 60,000. The development of streaming sites, peer-to-peer file sharing (P2P) networks, and tube sites led to a subsequent decline in the sale of DVDs and adult magazines.

Starting in the 21st century, greater access to the Internet and affordable smartphones made pornography more accessible and culturally mainstream. The total number of pornographic websites in 2012 was estimated to be around 25 million comprising 12% of all the websites. About 75 percent of households in the US gained Internet access by 2012. Data from 2015 suggests an increase in pornography consumption over the past few decades which is attributed to the growth of Internet pornography. Technological advancements such as digital cameras, laptops, smartphones, and Wi-Fi have democratized the production and consumption of pornography. Subscription-based service providers such as OnlyFans, founded in 2016, are becoming popular as the platforms for pornography trade in the digital era. Apart from the professional pornographers, content creators on such platforms include others like; a physics teacher, a race car driver, a woman undergoing cancer treatment. In 2022, the total pornographic content accessible online was estimated to be over 10,000 terabytes.

AVN and XBIZ are the industry-specific organizations based in the US that provide information about the adult entertainment business. XBIZ Awards and AVN Awards, analogous to the Golden globes and Oscars, are the two prominent award shows of the adult entertainment industry. Free Speech Coalition (FSC) is a trade association and Adult Performer Advocacy Committee (APAC) is a labor union for the adult entertainment industry based in the US. The scholarly study of pornography notably in cultural studies is limited. Porn Studies, which began in 2014, is the first international peer-reviewed, academic journal that is exclusively dedicated to the critical study of the "products and services" identified to constitute pornography.

Classifications

Adult content classifications

Adult content is generally classified as either pornography or erotica. Considerations of distinctness between pornography and erotica is mostly subjective. Pornographic content is categorized as softcore or hardcore. Softcore pornography contains depictions of nudity but without explicit depiction of sexual activity. Hardcore pornography includes explicit depiction of sexual activity. Hardcore porn is more regulated than softcore porn. Softcore porn was popular between the 1970s and 1990s.

Mainstream pornography

Pornography productions cater to consumers of various sexual orientations. Nonetheless, pornography featuring heterosexual acts made for heterosexual consumers, comprise the bulk of what is called the "mainstream porn", marking the industry more or less as "heteronormative".

Mainstream pornography involves professional performers who work for various corporate film studios in their respective productions.

Mainstream pornography productions are usually classified as feature or gonzo. Features involve storylines, characterizations, scripted dialog, elegant costumes, detailed sets, and soundtracks, which make the productions look similar to mainstream Hollywood productions but with the depictions of explicit sexual activity included. Features contain both original narratives as well as parodies that parody mainstream feature films, TV shows, celebrities, video games or literary works. Gonzo is a form of content creation that attempts to put the viewer into the scene, this is commonly achieved by close-up camera work or performers talking to the audience; also called "wall-to-wall", gonzo involves some aspects of "breaking the fourth wall" between the audience and performers. The term "gonzo" is often misused as a genre to identify demeaning depictions, however gonzo is a film-making style and not a genre. Gonzo style is variably incorporated in the creation of all types or genres of adult content. Gonzos do not involve the expensive sets or the costly production values of features, which makes their production relatively inexpensive. From the mid-2010s about 95 percent of porn productions are gonzo.

Indie pornography

Pornography productions that are independent of mainstream pornographic studios are classified as indie (or) independent pornography. These productions cater to more specific audience, and often feature different scenarios and sexual activity compared to the mainstream porn. The performers in indie porn include real-life couples and regular people, who sometimes work in partnership with other performers. Apart from content creation the performers do the background work such as videography, editing, web development themselves, and distribute under their own brand. Paysites like Clips4Sale.com, MakeLoveNotPorn.tv, and PinkLabel.tv provide a platform to the web-based content of independent pornographers.

Genres

Pornography encompasses a wide variety of genres providing for an enormous range of consumer tastes. Most of the genres or types are named according to the depiction of sexual activity, these include: anal, creampie, cum shot, double penetration, fisting, threesome. Categorizations based on the age of the performers include: teens, milf, mature. Other categorizations based on gender and sexual identity include: lesbian, transsexual, queer, shemale; while those based on race include: ethnic, interracial. Others include: Mormon, zombie. Pornography also features numerous fetishes like: "'fat' porn, amateur porn, disabled porn, porn produced by women, queer porn, BDSM and body modification."

Commercialism

Pornography is commercialized mainly through the sale of pornographic films. Many adult films had theatrical releases during the 1970s corresponding with the Golden Age of Porn. A 1970 federal study estimated that the total retail value of hardcore pornography in the United States was no more than $5 million to $10 million. The release of the VCR by Sony Corporation for the mass market in 1975 marked the shift of people from watching porn in adult movie theaters, to the confines of their houses. The introduction of VHS brought down the production quality through the 1980s.

Starting in the 1990s, Internet eased the access to pornography. The pay-per-view model enabled people to buy adult content directly from cable and satellite TV service providers. According to Showtime Television network report, in 1999 adult pay-per-view services made $367 million, which was six times more than the $54 million earned in 1993. Although this development resulted in a decline in rentals, the revenues generated over the Internet, provided much financial gains for pornography producers and credit card companies among others. By the mid-1990s, the adult film industry had agents for performers, production teams, distributors, advertisers, industry magazines, and trade associations. The introduction of home video and the World Wide Web in the late twentieth century led to global growth in the pornography business. Performers got multi-film contracts. In 1998, Forrester Research reported that online "adult content" industry's estimated annual revenue is at $750 million to $1 billion.

Retail stores or sex shops engaged in the sale of adult entertainment material ranging from videos, magazines, sex toys and other products, significantly contributed to the overall commercialization of pornography. Sex shops sell their products on both online shopping platforms such as Amazon and on specialized websites.

| Commercialization of pornography | |||

|

In 2000, the total annual revenue from the sales and rentals of pornographic material in the US was estimated to be over $4 billion. The hotel industry through the sale of adult movies to their customers as part of room service, over pay-per-view channels, had generated an annual income of about $180-$190 million. Some of the major companies and hotel chains that were involved in the sale of adult films over pay-per-view platforms include; AT&T, Time Warner, DirecTV from General Motors, EchoStar, Liberty Media, Marriott International, Westin and Hilton Worldwide. The companies said their services are in response to a growing American market that wanted pornography delivered at home. Studies in 2001 had put the total US annual revenue (including video, pay-per-view, Internet and magazines) between $2.6 billion and $3.9 billion.

Economics

The production and distribution of pornography are economic activities of some importance. In Europe, Budapest is regarded as the industry center. Other pornography production centers in the world are located in Florida (US), Brazil, Czech Republic, and Japan. In the United States, the pornography industry employs about 20,000 people including 2,000 to 3,000 performers, and is centered in the San Fernando Valley of Los Angeles. By 2005, it became the largest pornography production center in the world. Apart from regular media coverage, the industry in the US receives considerable attention from private organizations, government agencies, and political organizations.

As of 2011, pornography was becoming one of the biggest businesses in the United States. In 2014, the porn industry was believed to bring in at least $13 billion on a yearly basis in the United States. Through the 2010s, many pornography production companies and top pornographic websites such as Pornhub, RedTube and YouPorn have been acquired by MindGeek, a company that has been described as "a monopoly" in the pornography business. This development was identified as a problem. According to Marina Adshade, a professor from the Vancouver School of Economics and the author of Dollars and Sex: How economics influences sex and love, having a monopoly in the pornography business has forced the producers to reduce their charges, and radically changed the work of performers "who are now under greater pressure to perform acts that they would have been able to refuse in the past", all at a lower price without profits for themselves.

Online pornography is available both for a fee and free of charge. The availability of free porn on the Internet has led to a decline in the business of mainstream pornography. Piracy is estimated to result in losses of some $2 billion a year for the porn industry. Budgets of many studios reduced considerably and contracts for performers became less common. Reportedly, applications by established pornography companies for porn-shoot permits in Los Angeles County fell by 95 percent during the period 2012 to 2015. According to Mark Spiegler, an adult talent agent, in the early 2000s female performers made about $100,000 a year. By 2017, the amount is about $50,000.

The technological era led to decline of the studio and "the rise of the pornography worker herself". Newer ways of monetization have opened for the pornography workers who are taking the path of entrepreneurship. In 1995, Jenna Jameson signed her first contract with the porn studio Wicked Pictures. After building a brand image for herself she started her own company ClubJenna, which by 2005 was reportedly earning an annual revenue of $30-$35 million. "Performers are hustlers now," said Chanel Preston (a performer who was also chairperson of the Adult Performer Advocacy Committee), while noting that performers have to be creative to sustain their income and reach audience, both of which, she said are mainly achieved through "feature dancing, selling merchandise, webcamming", among other activities. "Custom" pornography made according to the requests of customer clients has emerged as one new business niche. The average career for the new age performer lasts about four to six months. Before moving on to the business side, adult performers use studio works to advertise and build a brand image for themselves. They acquire an audience who would later pay at personal website or webcam performances. Commercial webcamming, which emerged in the 1990s as a niche sector in the adult entertainment industry, grew to become a multibillion-dollar business by the mid-2020s.

The exact economic size of the porn industry in the early-twenty-first century is unknown to anyone. Kassia Wosick, a sociologist from New Mexico State University, estimated the global porn market value at $97 billion in 2015, with the US revenue estimated at $10 and $12 billion. IBISWorld, a leading researcher of various markets and industries, calculated total US revenue to reach $3.3 billion by 2020. On the basis of a research report by a market analysis firm, USA Today published that the estimated worth of the adult entertainment industry market in 2023 is over $172 billion.

Technology

Pornographers have taken advantage of each major technological advancement for the production and distribution of their services. Pornography has been called an "erotic engine" and a driving force in the development of various media related technologies from the printing press, through photography (still and motion), to satellite TV, Home video, and streaming media.

One of the world's leading anti-pornography campaigners, Gail Dines, has stated that "the demand for porn has driven the development of core cross-platform technologies for data compression, search, transmission and micro-payments." Many of the technological developments that had been led by pornography have benefited other fields of human activity too. In the early 2000s, Wicked Pictures pushed for the adoption of the MPEG-4 file format ahead of others, this later became the most commonly used format across high-speed Internet connections. In 2009, Pink Visual became one of the first companies to license and produce content with a software introduced by a small Toronto-based company called "Spatial view", which later made it possible to view 3D content on iPhones.

As an early adopter of innovations, the pornography industry has been cited to be a crucial factor in the development and popularization of various media processing and communication technologies. From innovative smaller film cameras, to the VCRs, and the Internet, the porn industry has employed newer technologies much ahead than other commercial industries, this early adoption provided the developers their early financial capital, which aided in the further development of these technologies. The success of innovative technologies is predicted by their greater use in the porn industry.

The way you know if your technology is good and solid is if it's doing well in the porn world.

Pornographic content accounted for most videotape sales during the late 1970s. The pornography industry has been considered an influential factor in deciding the format wars in media, including being a factor in the VHS vs. Betamax format war (the videotape format war) and the Blu-ray vs. HD DVD format war (the high-def format war). Piracy, the illegal copying and distribution of material, is of great concern to the porn industry. The industry has been the subject of many litigations and formalized anti-piracy efforts.

Many of the innovative data rendering procedures, enhanced payment systems, customer service models, and security methods developed by pornography companies have been co-opted by other mainstream businesses. Pornography companies served as the basis for a large number of innovations in web development. Much of the IT work in porn companies is done by people who are referred to as a "porn webmaster", often paid well in what are small businesses, they have more freedom to test innovations compared to other IT employees in larger organizations who tend to be risk-averse.

Virtual reality pornography

Some pornography is produced without human actors at all. The idea of computer-generated pornography was conceived very early as one of the obvious areas of application for computer graphics. Until the late 1990s, digitally manipulated pornography could not be produced cost-effectively. In the early 2000s, it became a growing segment as the modeling and animation software matured, and the rendering capabilities of computers improved. Further advances in technology allowed increasingly photorealistic 3D figures to be used in interactive pornography. The first pornographic film to be shot in 3D was 3D Sex and Zen: Extreme Ecstasy, released on 14 April 2011, in Hong Kong.

The various mediums for pornography depictions have evolved throughout the course of history, starting from prehistoric cave paintings, about forty millennia ago, to futuristic virtual reality renditions. Experts in the pornography business predict more people in the future would consume porn through virtual reality headsets, which are expected to give consumers better personal experiences than they can have in the real world. Speculations are rife about an increased presence of sex robots in the future pornography productions.

Consumption

Pornography is a product made by adults-for the consumption by adults, the consumption of which has become more common among people due to the expansive use of the Internet. About 90% of pornography is consumed on the Internet with consumers preferring content that is in tune with their sexuality. Pornography has been found to be a significant influencer of people's ideas about sex in the digital age. Pornographic websites rank among the top 50 most visited websites worldwide. XVideos and Pornhub are the two most visited pornographic websites worldwide.

Pornography consumption in people is found to induce "psychological moods and emotions" similar to those evoked during actual sexual intercourse and casual sex. Researchers identified four broad motivating factors for pornography consumption: an innate sexual drive or desire, to learn about sex and improve ones own sexual performance, peer pressure or social groups, lack of sexual relationship or absence of partner. Majority of pornography consumers tend to be male, unmarried, with higher levels of education. Younger people are more frequent consumers of porn than older people. There's been a gradual increase in the consumption rates across different age groups with the increased availability of free porn over the Internet.

Researchers at McGill University ascertained that on viewing pornographic content, men reached their maximum arousal in about 11 minutes and women in about 12 minutes. An average visit to a pornographic website lasts for 11.6 minutes. Both marriage and divorce are found to be associated with lower subscription rates for adult entertainment websites. Subscriptions are more widespread in regions that have higher measures of social capital. Pornographic websites are most often visited during office hours. As per a recent CNBC report, seventy per cent of online-porn access in the US happens between nine-to-five hours.

Sexual arousal and sexual enhancement tend to be the primary motivations among the self-reported reasons by users for their pornography consumption. Studies had found that greater levels of psychological distress leads to higher rates of pornography consumption. Pornography may provide a temporary relief from stress, or anxiety. A need to assuage coping and boredom is also found to result in higher consumption of pornography.

By Gender

A study of Austrian adults found that men consume pornography more frequently than women. The intent for consumption may vary, with men being more likely to use pornography as a stimulant for sexual arousal during solitary sexual activity, while women are more likely to use pornography as a source of information or entertainment, and rather prefer using it together with a partner to enhance sexual stimulation during partnered sexual activity. Studies have found that sexual functioning defined as "a person's ability to respond sexually or to experience sexual pleasure" is greater in women who consume pornography frequently than in women who do not. No such association was noticed in men. Women who consume pornography are more likely to know about their own sexual interests and desires, and in turn be willing and able to communicate them during partnered sexual activity, it has been reported that in women the ability to communicate their sexual preferences is associated with greater sexual satisfaction for themselves. Pornographic material is found to expand the sexual repertoire in women by making them learn new rewarding sexual behaviors such as clitoral stimulation and enhance their overall "sexual flexibility". Women who consume pornography frequently are more easily aroused during partnered sex and are more likely to engage in oral sex compared to the women who do not view pornography. Women users of pornography had reported (almost 50%) to have had engaged in cunnilingus, which research suggests is related to female orgasm, and to have had experienced orgasms more frequently than women who do not use pornography (87% vs. 64%). Most people, probably do not consider pornography use by a partner as indulging in infidelity.

By education level

A two year long survey (2018–2020) conducted to assess the role of pornography in the lives of highly educated medical university students, with median age of 24, in Germany found that pornography served as an inspiration for many students in their sex life. Pornography use among students was higher in males than in females, among the male students those who did not cheat on their partner or contracted an STI were found to be more frequent consumers of pornography. Although pornography use was more common among men, associations between pornography use and sexuality were more apparent in women. Among the female students, those who reported to be satisfied with their physical appearance have consumed three times as much pornography than the female students who had reported to be dissatisfied with their body. A feeling of physical inadequacy was found to be a restraining factor in the consumption of pornography. Female students who consume pornography more often had reported to have had multiple sexual partners. Both female and male students who enjoyed the experience of anal intercourse in their life were reported to be frequent consumers of pornography. Sexual content depicting bondage, domination, or violence was consumed by only a minority of 10%. More sexual openness and less sexual anxiety was observed in students who regularly consumed pornography. No association was noticed between regular pornography use and experience of sexual dissatisfaction in either female or male students. This finding was in concurrence with another finding from a longitudinal study, which demonstrated most pornography consumers differentiate pornographic sex from real partnered sex and do not experience diminishing satisfaction with their sex life.

By region

A vast majority of men and considerable number of women in the US use porn. A study in 2008 found that among University students aged 18 to 26 located in six college sites across the United States, 67% of young men and 49% of young women approved pornography viewing, with nearly 9 out of 10 men (87%) and 31% women reportedly using pornography. The Huffington Post reported in 2013 that porn websites registered higher number of visitors than Netflix, Amazon, and Twitter combined. A 2014 poll, which asked Americans when they had "last intentionally looked at pornography", elicited a result that 46% of men and 16% of women in the age group of 18–39 did so in the past week. A 2016 study reported that about 70% of men and 34% of women in romantic relationships use pornography annually. Gallup poll surveys conducted over the years 2011 to 2018 noted a gradual increase in the acceptance rates of pornography among the general American public.

Since the late 1960s, attitudes towards pornography have become more positive in Nordic countries; in Sweden and Finland the consumption of pornography has increased over the years. A 2006 study of Norwegian adults found that over 80% of the respondents used pornography at some point in their lives, a difference of 20% was observed between men and women in their respective use. A 2015 study in Finland noted that 75% of the 30-40-y.o. women and above 90% of the 30-40-y.o. men found porn "very exciting". Of those who had watched porn during the latest year, 71% of the 18-24-y.o. women, almost 60% of the 18-49-y.o. women, and a tenth of 65+ women did so; among men, the numbers were above 90% of the men under 50-y.o., 3/4 of the 18-64-y.o. and most of the 65+ y.o.; the numbers were quickly increasing, particularly for women, partially due to increased masturbation.

In 2012 and 2013, interviews with large number of Australians revealed that in the past year 63% of men and 20% of women had viewed pornography.

A 2020 Egyptian study surveying 15,027 individuals in Arab countries noted a prevalence of pornography use "nearly similar to Danish, German, and American ones".

In 2021, it was estimated that in modern countries, 46–74% of men and 16–41% of women are regular users of pornography. In 2022, a national survey in Japan, of men and women aged 20 to 69 revealed that 76% of men and 29% of women had used pornography as part of their sexual activity. A 2023 study reported that in Netherlands, young men who watched porn in the previous six months ranged between 65% (13–15-y.o.) to 96% (22–24-y.o.), and among young women between 22% (13–15-y.o.) to 75% (22–24-y.o.).

Legality and regulations

The legal status of pornography varies widely from country to country. Regulating hardcore pornography is more common than regulating softcore pornography. Child pornography is illegal in almost all countries, and some countries have restrictions on rape pornography and zoophilic pornography.

Pornography in the United States is legal provided it does not depict minors, and is not obscene. The community standards, as indicated in the Supreme Court decision, of the 1973 Miller v. California case determine what constitutes as "obscene". The US courts do not have jurisdiction over content produced in other countries, but anyone distributing it in the US is liable to prosecution under the same community standards. As the courts consider community standards foremost in deciding any obscenity charge, the changing nature of community standards over the course of time and place makes instances of prosecution limited.

In the United States, a person receiving unwanted commercial mail that he or she deems pornographic (or otherwise offensive) may obtain a Prohibitory Order. Many online sites require the user to tell the website they are a certain age and no other age verification is required. A total of 16 states and the Republican Party have passed resolutions declaring pornography a "public health" threat. These resolutions are symbolic and do not put any restrictions but are made to sway the public opinion on pornography. The notion of pornography as a threat to public health is not supported by any international health organization.

The adult film industry regulations in California requires that all performers in pornographic films use condoms. However, the use of condoms in pornography is rare. As porn does better financially when actors are without condoms many companies film in other states. Twitter is the popular social media platform used by the performers in porn industry as it does not censor content unlike Instagram and Facebook.

Pornography in Canada, as in the US, criminalizes the "production, distribution, or possession" of materials that are deemed obscene. Obscenity, in the Canadian context, is defined as "the undue exploitation of sex" provided it is connected to images of "crime, horror, cruelty, or violence". As to what is considered "undue" is decided by the courts, which assess the community standards in deciding whether exposure to the given material may result in any harm, with harm defined as "predisposing people to act in an anti-social manner".

Pornography in the United Kingdom does not have the concept of community standards. Following the highly publicized murder of Jane Longhurst, the UK government in 2009 criminalized the possession of what it terms as "extreme pornography". The courts decide whether any material is legally extreme or not, conviction for penalty include fines or incarceration up to three years. Content banned includes representations that are considered "grossly offensive, disgusting, or otherwise of an obscene character". While there are no restrictions on depiction of male ejaculation, any depiction of female ejaculation in pornography is completely banned in the UK, as well as in Australia.

In most of Southeast Asia, Middle East, and China, the production, distribution, and/or possession of pornography is illegal and outlawed. In Russia and Ukraine, webcam modeling is allowed provided it contains no explicit performances; in other parts of the world commercial webcamming is banned as a form of pornography.

Disseminating pornography to a minor is generally illegal. There are various measures to restrict minors' any access to pornography, including protocols for pornographic stores.

Pornography can infringe into basic human rights of those involved, especially when sexual consent was not obtained. Revenge porn is a phenomenon where disgruntled sexual partners release images or video footage of intimate sexual activity of their partners, usually on the Internet, without authorization or consent of the individuals involved. In many countries there has been a demand to make such activities specifically illegal carrying higher punishments than mere breach of privacy, or image rights, or circulation of prurient material. As a result, some jurisdictions have enacted specific laws against "revenge porn".

What is not pornography

In the US, a July 2014 criminal case decision in Massachusetts — Commonwealth v. Rex, 469 Mass. 36 (2014), made a legal determination as to what was not to be considered "pornography" and in this particular case "child pornography". It was determined that photographs of naked children that were from sources such as National Geographic magazine, a sociology textbook, and a nudist catalog were not considered pornography in Massachusetts even while in the possession of a convicted and (at the time) incarcerated sex offender.

Drawing the line depends on time, place and context. Occidental mainstream culture has been increasingly getting "pornified" (i.e. influenced by pornographic themes, with mainstream films often including unsimulated sexual acts). Since the very definition of pornography is subjective, material that is considered erotic or even religious in one society may be denounced as pornography in another. When European travellers visited India in the 19th century, they were dismayed at the religious representation of sexuality on the Hindu temples and deemed them as pornographic. Similarly many films and television programs that are unobjectionable in contemporary Western societies are labeled as "pornography" in Muslim societies. Thus, assessing a material as pornography is very much personalized; to rehash a cliché, "pornography is very much in the eye of the beholder".

Copyright status

In the United States, some courts have applied US copyright protection to pornographic materials. Some courts have held that copyright protection effectively applies to works, whether they are obscene or not, but not all courts have ruled the same way. The copyright protection rights of pornography in the United States has again been challenged as late as February 2012.

STIs prevention and safer sex practices

Performers working for pornographic film studios undergo regular testing for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) every two weeks. They have to test negative for: HIV, trichomoniasis, chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, and hepatitis B and C before showing up on a set and are then inspected for sores on their mouths, hands, and genitals before commencing work. The industry believes this method of testing to be a viable practice for safer sex as its medical consultants claim that since 2004, about 350,000 pornographic scenes have been filmed without condoms and HIV has not been transmitted even once because of performance on set. However, some studies suggest that adult film performers have high rates of chlamydia and/or gonorrhea infection, and many of these cases may be missed by industry screening because these bacteria can colonize many sites on the body.

In the initial years, studios assessed performers suitability on the results from their blood and urine tests. According to a 2019 study by the American College of Emergency Physicians, swab tests offer better insight than urine samples for detecting bacterial STIs like chlamydia and gonorrhea. Performers such as Cherie DeVille have emphasized swab tests for safer sex. According to performer Angela White, studios will not allow them to work unless they are completely clean, insisting on performers testing regularly, she said "So for me, because I work so much, I’m testing every 12 days – and that is a full sweep of STIs such as chlamydia, gonorrhoea, syphilis, HIV and trichomoniasis. We’re doing throat swabs, vaginal swabs and anal swabs." Allan Ronald, a Canadian doctor and HIV/AIDS specialist who did groundbreaking studies on the transmission of STIs among prostitutes in Africa, said there's no doubt about the efficiency of the testing method, but he felt a little uncomfortable: "because it's giving the wrong message — that you can have multiple sex partners without condoms — but I can't say it doesn't work."

Relatedly, it has been found that individuals who received little sex education and/or perceive pornography as a source of information about sex, are less apt to use condoms in their own sex life, making themselves more susceptible to contract STIs. In 2020—the US National Sex Education Standards—released recommendations to incorporate "porn literacy" to students from grade 6 to 12 as part of sex education in the US.

Veteran performer and former nurse Nina Hartley, who has a degree in nursing, stated that the amount of time involved in shooting a scene can be very long, and with condoms in place it becomes a painful proposition as their usage is uncomfortable despite the use of lube, causes friction burn, and opens up lesions in the genital mucosa. Advocating the testing method for performers, Hartley said, "Testing works for us, and condoms work for outsiders."

"We're tested every fourteen days. That is literally twenty-three more times than the average American. If that person makes it to their yearly physical. I have met tons of people that haven't been to the doctor in years. That scares me because they have no idea what their status is.... I don't hook up with people outside of the porn industry because I'm terrified. And I'm not the only one. There's many performers that know: if you go out into the wild, you will come back with something." — Ash Hollywood (Porn actress).

Emphasizing that performers in the industry take necessary precautions like PrEP and are at lower risk to contract HIV than most sexually active persons outside the industry, many prominent female performers have vehemently opposed regulatory measures like Measure B that sought to make the use of condoms mandatory in pornographic films. Professional female performers have called the use of condoms on a daily basis at work an occupational hazard as they cause micro-tears, friction burn, swelling, and yeast infections, which altogether, they say, makes them more susceptible to contract STIs.

Views on pornography

Pornography has been vouched to provide a safe outlet for sexual desires that may not be satisfied within relationships and be a facilitator of sexual fulfillment in people who cannot or do not want to have real-life partners. Pornography is viewed by people in general for various reasons; varying from a need to enrich their sexual arousal, to facilitate orgasm, as an aid for masturbation, learn about sexual techniques, reduce stress, alleviate boredom, enjoy themselves, see representation of people like themselves, know their sexual orientation, improve their romantic relationships, or simply because their partner wants them to.

Pornography is noted for engrossing people "on more than masturbatory levels". Aesthetic philosophers argue whether pornographic representations can be considered as expressions of art. Pornography has been equated with journalism as both offer a view into the unknown or the hidden aspects. French philosopher Michel Foucault remarked that, "it is in pornography that we find information about the hidden, the forbidden and the taboo".

Scholars such as Linda Williams, Jennifer Nash, and Tim Dean believe pornography "is a form of thinking", comprised with ideas that are way more reflective about sexuality and gender than what the creators or consumers of pornography intend. Pornography has been referred by people as a means to explore their sexuality. People have reported porn being helpful in learning about human sexuality in general. Studies recommend clinical practitioners to use pornography as an instruction aid to show their clients new and alternative sexual behaviors as part of psychosexual therapy. British psychologist, Oliver James, known for his work on 'happiness', stated that "a high proportion of men use porn as a distraction or to reduce stress ... It serves an anti-depressant purpose for the unhappy."

Feminist outlook

Overall

Feminist movements in the late 1970s and 1980s dealt with the issues of pornography and sexuality in debates that are referred to as the "sex wars". While some feminist groups seek to abolish pornography believing it to be harmful, other feminist groups oppose censorship efforts insisting it is benign. A large scale study of data from the General Social Survey (2010–2018) refuted the argument that pornography is inherently anti-woman or anti-feminist and that it drives sexism. The study did not find a relationship between "pornography viewing" and "pornography tolerance" with higher sexism—a posit that was held by some feminists; it instead found higher pornography consumption and pornography tolerance among men to be associated with their greater support for gender equality. The study concluded that "pornography is more likely to be about the sex rather than the sexism".

People who supported regulated pornography expressed lesser attitudes of sexism than people who sought to abolish pornography. Notably, non-feminists are found more likely to support a ban on pornography than feminists. Many feminists, both male and female, have reflected that the effects of pornography on society are neutral. Adult users of pornography were found more egalitarian than nonusers, they are more likely to hold favorable attitudes towards women in positions of power and in workplaces outside home than the nonusers.

Critical

A 2016 study authored by Black feminists criticized the American adult entertainment industry for alleged omission and exclusion of Black women in pornographic representations, particularly in the interracial genres. As pornography becomes a kind of manual on how bodies in pleasure can look, and is "one of the few places where we see our bodies--and other people's bodies," it becomes imperative on pornography to represent "variety of forms", stated the feminist scholars. Anti-pornography feminists argue that aesthetics of pornography demote Black women with undertones of racism. Gender studies scholars Mireille Miller-Young and Jennifer Christine Nash, in their writings on intersectionality of race and pornography, noted that Black people have been depicted as being hypersexual and Black women—more objectified. The scholars also noted major discrepancies in pay rates of the performers, White women have historically made 75 percent more per scene and sometimes still make 50 percent more compared to Black women.

Feminist resentment about pornography tend to focus on two concerns: that pornography depicts violence and aggression, and that pornography objectifies women. Multiple analyses of pornographic videos found that Women have been overwhelmingly at the receiving end of aggression from male performers; with the reaction of Women being either positive or neutral towards aggression, which is at odds considering a report that found only 14.2% of US adult women find pain during sex as appealing. Two studies in the 1990s found that Black women were the targets of aggression and faced more violence from both Black and White men than did White women. However, more recent research from 2018 found that Black women were the least likely group of women to suffer nonconsensual aggression and are more likely to receive affection from their male partners. While Black men engaged in fewer intimate behaviors than White men; White women were found more likely to experience violence during sexual activity with White men than with Black men.

Concerning Asian women, a 2016 study based on a sample of 3053 videos from Xvideos.com, found that in the 170 videos of the Asian women category, there was much less aggression, less objectification, but also the women had less agency. However, another study found that in a sample of 172 videos from Pornhub, the 25+ videos of the Asian/Japanese category had considerably more aggression than those of other categories. A 2002 study of "internet rape sites" found that among the 56 clear pictures they found, 34 had Asian women, and nearly half the sites had either an image or a text reference to an Asian woman. Findings on depictions of Asian women in pornography aren't consistent in scientific literature.

The prevalence of aggression in pornography appears to be changing. A 2018 study of popular videos on Pornhub found that segments of aggression towards women are fewer now, and they have reduced gradually over the past decade with viewers preferring content where women genuinely experience pleasure.

Anti-porn

Prominent anti-pornography feminists such as Andrea Dworkin and Catharine MacKinnon argue that all pornography is demeaning to women, or that it contributes to violence against women–both in its production and in its consumption. The production of pornography, they argue, entails the physical, psychological, or economic coercion of the women who perform in it. They charged that pornography eroticizes the domination, humiliation, and coercion of women, while reinforcing sexual and cultural attitudes that are complicit in rape and sexual harassment.

Other sex work exclusionary feminists have insisted that pornography presents a severely distorted image of sexual consent, and it reinforces sexual myths like: women are readily available–and desire to engage in sex at any time–with any man–on men's terms–and always respond positively to men's advances.

Pro-porn

In contrast to the objections, other feminist scholars "ranging from Betty Friedan and Kate Millett to Karen DeCrow, Wendy Kaminer and Jamaica Kincaid" have supported the right to consume pornography. The anti-porn feminist stranglehold began to loose when sex-positive feminists like Susie Bright, performers Nina Hartley, and Candida Royalle affirmed the rights of women to consume and produce porn.