Fraser River

Naming

The river is named after Simon Fraser, who led an expedition in 1808 on behalf of the North West Company from the site of present-day Prince George almost to the mouth of the river. The river's name in the Halqemeylem (Upriver Halkomelem) language is Sto:lo, often seen archaically as Staulo, and has been adopted by the Halkomelem-speaking peoples of the Lower Mainland as their collective name, Sto:lo. The river's name in the Dakelh language is Lhtakoh. The Tsilhqot'in name for the river, not dissimilar to the Dakelh name, is ʔElhdaqox, meaning Sturgeon (ʔElhda-chugh) River (Yeqox).

Course

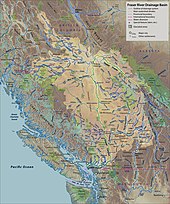

The Fraser drains a 220,000-square-kilometre (85,000 sq mi) area. Its source is a dripping spring at Fraser Pass in the Canadian Rocky Mountains near the border with Alberta. The river then flows north to the Yellowhead Highway and west past Mount Robson to the Rocky Mountain Trench and the Robson Valley near Valemount. After running northwest past 54° north, it makes a sharp turn to the south at Giscome Portage, meeting the Nechako River at the city of Prince George, then continues south, progressively cutting deeper into the Fraser Plateau to form the Fraser Canyon from roughly the confluence of the Chilcotin River, near the city of Williams Lake, southwards. It is joined by the Bridge and Seton Rivers at the town of Lillooet, then by the Thompson River at Lytton, where it proceeds south until it is approximately 64 kilometres (40 mi) north of the 49th parallel, which is Canada's border with the United States.

From Lytton southwards it runs through a progressively deeper canyon between the Lillooet Ranges of the Coast Mountains on its west and the Cascade Range on its east. Hell's Gate, located immediately downstream of the town of Boston Bar, is a famous portion of the canyon where the walls narrow dramatically, forcing the entire volume of the river through a gap only 35 metres (115 feet) wide. An aerial tramway takes visitors out over the river. Hells Gate is visible from Trans-Canada Highway 1 about 2 km (1.2 mi) south of the tramway. Simon Fraser was forced to portage the gorge on his trip through the canyon in June 1808.

At Yale, at the head of navigation on the river, the canyon opens up and the river widens, though without much adjoining lowland until Hope, where the river then turns west and southwest into the Fraser Valley, a lush lowland valley, and runs past Chilliwack and the confluence of the Harrison and Sumas Rivers, bending northwest at Abbotsford and Mission.

The Fraser then flows past Maple Ridge, Pitt Meadows, Port Coquitlam, and north Surrey. It turns southwest again just east of New Westminster, where it splits into the North Arm, which is the southern boundary of the City of Vancouver, and the South Arm, which divides the City of Richmond from the City of Delta to the south. Richmond is on the largest island in the Fraser, Lulu Island and also on Sea Island, which is the location of Vancouver International Airport, where the Middle Arm branches off to the south from the North Arm. The far eastern end of Lulu Island is named Queensborough and is part of the City of New Westminster. Also in the lowermost Fraser, among other smaller islands, is Annacis Island, an important industrial and port area, which lies to the southeast of the eastern end of Lulu Island. Other notable islands in the lower Fraser are Barnston Island, Matsqui Island, Nicomen Island and Sea Bird Island. Other islands lie on the outer side of the estuary, most notably Westham Island, a wildfowl preserve, and Iona Island, the location of the main sewage plant for the City of Vancouver.

After 100 kilometres (about 60 mi), the Fraser forms a delta where it empties into the Strait of Georgia between the mainland and Vancouver Island. The lands south of the City of Vancouver, including the cities of Richmond and Delta, sit on the flat flood plain. The islands of the delta include Iona Island, Sea Island, Lulu Island, Annacis Island, and a number of smaller islands. While the vast majority of the river's drainage basin lies within British Columbia, a small portion in the drainage basin lies across the international border in Washington in the United States, namely the upper reaches of the tributary Chilliwack and Sumas rivers. Most of lowland Whatcom County, Washington is part of the Fraser Lowland and was formed also by sediment deposited from the Fraser, though most of the county is not in the Fraser drainage basin.

Similar to the Columbia River Gorge east of Portland, Oregon, the Fraser exploits a topographic cleft between two mountain ranges separating a more continental climate (in this case, that of the British Columbia Interior) from a milder climate near the coast. When an Arctic high-pressure area moves into the British Columbia Interior and a relatively low-pressure area builds over the general Puget Sound and Strait of Georgia region, the cold Arctic air accelerates southwest through the Fraser Canyon. These outflow winds can gust up to 97 to 129 kilometres per hour (60 to 80 mph) and have at times exceeded 160 kilometres per hour (100 mph). Such winds frequently reach Bellingham and the San Juan Islands, gaining strength over the open water of the Strait of Juan de Fuca.

The estuary at the river's mouth is a site of hemispheric importance in the Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserve Network.

Discharge

The Water Survey of Canada currently operates 17 gauge stations that measure discharge and water level along the majority of the mainstem from Red Pass just downstream of Moose Lake in the Mount Robson Provincial Park, to Steveston in Vancouver at the river mouth. With an average flow at the mouth of about 3,475 cubic metres per second (122,700 cu ft/s), the Fraser is the largest river by discharge flowing into the Pacific seaboard of Canada and the fifth largest in the country. The average flow is highly seasonal; summer discharge rates can be ten times larger than the flow during the winter.

The Fraser's highest recorded flow, in June 1894, is estimated to have been 17,000 cubic metres per second (600,000 cu ft/s) at Hope. It was calculated using high-water marks near the hydrometric station at Hope and various statistical methods. In 1948 the Fraser River Board adopted the estimate for the 1894 flood. It remains the value specified by regulatory agencies for all flood control work on the river. Further studies and hydraulic models have estimated the maximum discharge of the Fraser River, at Hope during the 1894 flood, as within a range of about 16,000 to 18,000 cubic metres per second (570,000 to 640,000 cu ft/s).

History

On June 14, 1792, the Spanish explorers Dionisio Alcalá Galiano and Cayetano Valdés entered and anchored in the North Arm of the Fraser River, becoming the first Europeans to find and enter it. The existence of the river, but not its location, had been deduced during the 1791 voyage of José María Narváez, under Francisco de Eliza.

The upper reaches of the Fraser River were first explored by Sir Alexander Mackenzie in 1793, and fully traced by Simon Fraser in 1808, who confirmed that it was not connected with the Columbia River.

The lower Fraser was revisited in 1824 when the Hudson's Bay Company sent a crew across Puget Sound from its Fort George southern post on the Columbia River. The expedition was led by James McMillan. The Fraser was reached via the Nicomekl River and the Salmon River reachable after a portage. Friendly tribes met earlier on by the Simon Fraser crew were reacquainted with. A trading post with agricultural potential was to be located.

By 1827, a crew was sent back via the mouth of the Fraser to build and operate the original Fort Langley. McMillan also led the undertaking. The trading post original location would soon become the first ever mixed ancestry and agricultural settlement in southern British Columbia on the Fraser (Sto:lo) river.

In 1828 George Simpson visited the river, mainly to examine Fort Langley and determine whether it would be suitable as the Hudson's Bay Company's main Pacific depot. Simpson had believed the Fraser River might be navigable throughout its length, even though Simon Fraser had described it as non-navigable. Simpson journeyed down the river and through the Fraser Canyon and afterwards wrote "I should consider the passage down, to be certain Death, in nine attempts out of Ten. I shall therefore no longer talk about it as a navigable stream". His trip down the river convinced him that Fort Langley could not replace Fort Vancouver as the company's main depot on the Pacific coast.

Much of British Columbia's history has been bound to the Fraser, partly because it was the essential route between the Interior and the Lower Coast after the loss of the lands south of the 49th Parallel with the Oregon Treaty of 1846. It was the site of its first recorded settlements of Aboriginal people (see Musqueam, Sto:lo, St'at'imc, Secwepemc and Nlaka'pamŭ), the site of the first European-Indigenous mixed ancestry settlement in southern British-Columbia (see Fort Langley), the route of multitudes of prospectors during the Fraser Canyon Gold Rush and the main vehicle of the province's early commerce and industry.

In 1998, the river was designated as a Canadian Heritage River for its natural and human heritage. It remains the longest river with that designation.

Uses

The Fraser is heavily exploited by human activities, especially in its lower reaches. Its banks are rich farmland, its water is used by pulp mills, and a few dams on some tributaries provide hydroelectric power. The main flow of the Fraser has never been dammed partly because its high level of sediment flows would result in a short dam lifespan, but mostly because of strong opposition from fisheries and other environmental concerns. In 1858, the Fraser River and surrounding areas were occupied when the gold rush came to the Fraser Canyon and the Fraser River. It is also a popular fishing location for residents of the Lower Mainland.

The delta of the river, especially in the Boundary Bay area, is an important stopover location for migrating shorebirds.

The Fraser Herald, a regional position within the Canadian Heraldic Authority is named after the river.

Fishing

The Fraser River is known for the fishing of white sturgeon, all five species of Pacific salmon (chinook, coho, chum, pink, sockeye), as well as steelhead trout. The Fraser River is also the largest producer of salmon in Canada. A typical white sturgeon catch can average about 500 pounds (230 kg). A white sturgeon weighing an estimated 500 kilograms (1,100 lb) and measuring 3.76 metres (12 ft 4 in) was caught and released on the Fraser River in July 2012. In 2021, a white sturgeon was caught on the river weighing 890 pounds (400 kg), with a length of 352 cm (11.55 ft). It was estimated to be over 100 years old. The fish was tagged and released.

Flooding

The most significant Fraser river floods in recorded history occurred in 1894 and 1948.

1894 flood

After European settlement, the first disastrous flood in the Lower Mainland (Fraser Valley and Metro Vancouver) occurred in 1894. With no protection against the rising waters of the Fraser River, Fraser Valley and Metro Vancouver communities from Chilliwack downstream were inundated with water. In the 1894 floods, the water mark at Mission reached 7.85 metres (25.75 ft).

After the 1894 flood, a dyking system was constructed throughout the Fraser Valley. The dyking and drainage projects greatly improved the flood problems, but over time, the dykes were allowed to fall into disrepair and became overgrown with brush and trees. With some dykes constructed of a wooden frame, they gave way in 1948 in several locations, marking the second disastrous flood. Flooding since 1948 has been minor in comparison.

1948 flood

1948 saw massive flooding in Chilliwack and other areas along the Fraser River. The high-water mark at Mission rose to 7.5 metres (24.7 ft). The peak flow was about 15,600 cubic meters per second.

Timeline

- On May 28, 1948, the Semiault Creek Dyke broke.

- On May 29, 1948, dykes near Glendale (now Cottonwood Corners) gave way and in four days, 49 square kilometres (12,000 acres) of fertile ground were under water.

- On June 1, 1948, the Cannor Dyke (east of Vedder Canal near Trans Canada Highway) broke and released tons of Fraser River water onto the Greendale area, destroying homes and fields.

- On June 3, 1948, the steamer Gladys supplied flood-stricken Chilliwack with tents and provisions as well as moving people and stock onto high ground.

Causes

Cool temperatures in March, April, and early May had delayed the melting of the heavy snowpack that had accumulated over the winter season. Several days of hot weather and warm rains over the holiday weekend in late May hastened the thawing of the snowpack. Rivers and streams quickly swelled with spring runoff, reaching heights surpassed only in 1894. Finally, the poorly maintained dyke systems failed to contain the water.

At the height of the 1948 flood, 200 square kilometres (50,000 acres) stood under water. Dykes broke at Agassiz, Chiliwack, Nicomen Island, Glen Valley and Matsqui. When the flood waters receded a month later, 16,000 people had been evacuated, with damages totaling $20 million, about $225 million in 2020 dollars.

1972 flood

Major flooding occurred once again in 1972 due to a significant spring freshet, primarily impacting regions around Prince George, Kamloops, Hope and Surrey.

2007 flood

Due to record snowpacks on the mountains in the Fraser River catch basin which began melting, combined with heavy rainfall, water levels on the Fraser River rose in 2007 to a level not reached since 1972. Low-lying land in areas upriver such as Prince George suffered minor flooding. Evacuation alerts were given for the low-lying areas not protected by dikes in the Lower Mainland. However, the water levels did not breach the dikes, and major flooding was averted.

2021 flood

Major flooding occurred in November 2021 as part of the November 2021 Pacific Northwest floods.

Tributaries

Tributaries are listed from the mouth of the Fraser and going up river.

- Brunette River

- Coquitlam River

- Pitt River

- Stave River

- Kanaka Creek

- D'Herbomez Creek

- Norrish Creek

- Sumas River

- Harrison River

- Ruby Creek

- Coquihalla River

- Emory Creek

- Spuzzum Creek

- Anderson River

- Nahatlatch River

- Thompson River

- Stein River

- Seton River

- Bridge River

- Churn Creek

- Chilcotin River

- Williams Lake River

- Quesnel River

- Cottonwood River

- West Road River (Blackwater River)

- Nechako River

- Salmon River

- Willow River

- McGregor River

- Bowron River

- Torpy River

- Morkill River

- Goat River

- Doré River

- Holmes River

- Castle Creek

- Raush River

- Kiwa Creek

- Tete Creek

- McLennan River

- Swiftcurrent Creek

- Robson River

- Moose River

See also

- List of crossings of the Fraser River

- List of crossings of the Thompson River

- List of crossings of the Nechako River

- List of longest rivers of Canada

- French Bar Canyon

- Fraser Canyon

- List of rivers of British Columbia

- Moran Dam (proposal)

- Vanport Oregon flood May 30, 1948

References

- ^ Salishan languages and Chinook Jargon. The Halkomelem form is Sto:lo, used as the name of the people of the Fraser Valley stretch of the river. "Staulo" is the anglicization used in the Kamloops Wawa lexicon of the Chinook Jargon

- ^ Carrier language. Lhtako is also used to mean the Dakelh people of the Quesnel/North Cariboo area

- ^ Indigenous name recorded by Alexander Mackenzie on expedition to find Columbia River’s headwaters; circa 18-?

- ^ Tsilhqot'in name meaning Sturgeon (ʔElhdachogh) River (Yeqox)

- ^ "Fraser River Fact Sheet". Canadian Heritage Rivers System. Archived from the original on July 12, 2017. Retrieved December 2, 2016.

- ^ Ambient Water Quality Assessment and Objectives for the Fraser River sub-basin from Kanaka Creek to the Mouth Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, BC Ministry of Environment

- ^ "Comprehensive Review of Fraser River at Hope: Flood Hydrology and Flows, Scoping Study Final Report" (PDF). BC Ministry of Environment. October 2008. Retrieved October 11, 2009.

- ^ "Fraser River Delta". Ramsar Sites Information Service. Retrieved April 25, 2018.

- ^ "BC Geographical Names". Retrieved June 2, 2019.

- ^ Cannings, Richard and Sidney. British Columbia: A Natural History. p.41. Greystone Books. Vancouver. 1996

- ^ "Dakleh Placenames". www.ydli.org.

- ^ "North Arm Fraser River". BC Geographical Names.

- ^ Mass, Cliff (2008). The Weather of the Pacific Northwest. University of Washington Press. pp. 146–148. ISBN 978-0-295-98847-4.

- ^ "Description". Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserve Network. Retrieved February 18, 2008.

- ^ Real-Time Hydrometric Data Map Search – Water Level and Flow – Environment Canada

- ^ "Ambient Water Quality Assessment and Objectives for the Fraser River Sub-basin from Kanaka Creek to the Mouth". British Columbia Ministry of Environment, Water Management Branch, Resource Quality Section. November 1985. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved October 11, 2009.

- ^ Ferguson, John W.; Michael Healey (May 2009). "Hydropower in the Fraser and Columbia Rivers". Catch and Culture (newsletter). Mekong River Commission. Archived from the original on February 15, 2010. Retrieved October 11, 2009.

- ^ Hayes, Derek (1999). Historical Atlas of the Pacific Northwest: Maps of exploration and Discovery. Sasquatch Books. ISBN 1-57061-215-3.

- ^ Maclachlan, Morag (November 1, 2011). "Journal Kept by George Barnston, 1827-8". Fort Langley Journals, 1827-30. UBC Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-0774841979.

- ^ "Modest beginnings." "The Orca," February 2020

- ^ Mackie, Richard Somerset (1997). Trading Beyond the Mountains: The British Fur Trade on the Pacific 1793–1843. Vancouver: University of British Columbia (UBC) Press. p. 58. ISBN 0-7748-0613-3.

- ^ "Fraser River". Canadian Council for Geographic Education. Archived from the original on April 17, 2005.

- ^ "Welcome". www.reifelbirdsanctuary.com.

- ^ Lapointe, Mike; Cooke, Steven J.; Hinch, Scott G.; Farrell, Anthony P.; Jones, Simon; MacDonald, Steve; Patterson, David; Healey, Michael C.; Van Der Kraak, Glen (2003). "Late-run sockeye salmon in the Fraser River, British Columbia are experiencing early upstream migration and unusually high rates of mortality: what is going on" (PDF). Proceedings of the 2003 Georgia Basin/Puget Sound Research Conference, Vancouver, BC. 31: 1–14.

- ^ "Sturgeon Weight/Age Chart". Rivermen Rod and Gun Club.

- ^ "Giant 12 foot Sturgeon caught on Fraser River « Great River Fishing Adventures". greatriverfishing.com.

- ^ "Record sturgeon catch on Fraser River 'a lifetime moment' for ex-NHL goalie and friends". vancouversun.

- ^ "PHOTOS: Looking back at the floods of 1894 and 1948 in Chilliwack". The Chilliwack Progress. June 14, 2020. Retrieved November 29, 2021.

- ^ "River flooding part of Hope history". Hope Standard. June 27, 2012. Retrieved November 29, 2021.

- ^ "Flooding events in Canada: British Columbia". Government of Canada. December 2, 2010. Retrieved November 29, 2021.

The greatest Fraser River flood in the past century occurred in 1894, when the floodplain areas were in the very early stages of settlement and development.

- ^ "North Delta history: The historic floods of May". Surrey Now Leader. May 12, 2019. Archived from the original on November 30, 2021. Retrieved November 29, 2021.

In May of 1894, the Fraser River had its largest recorded flood; Abbotsford and Chilliwack were particularly hard hit. North Delta lay above the flood waters, but farmers in South Westminster to the north and Ladner to the south faced weeks of their land and homes inundated with murky silt-laden water.

- ^ "Flooding events in Canada: British Columbia". Government of Canada. December 2, 2010. Retrieved November 29, 2021.

On June 10, 1948, the Fraser reached a peak elevation of 7.6 metres at Mission. Before the waters receded, over a dozen dyking systems had been breached and more than 22 000 hectares, nearly one third of the entire lower Fraser Valley floodplain area, had been flooded to this depth. The floodwaters severed the two transcontinental rail lines; inundated the Trans-Canada Highway; flooded urban areas such as Agassiz, Rosedale, and parts of Mission, forcing many industries to close or reduce production; and deposited a layer of silt, driftwood and other debris over the entire area.

- ^ "Flooding events in Canada: British Columbia". Government of Canada. December 2, 2010. Retrieved November 29, 2021.

On June 16, the lower Fraser peaked at Hope, with a maximum instantaneous flow of 3400 cubic metres per second and a maximum elevation of 7.1 metres, well above the danger level of 6.1 metres. Damage on the Fraser in 1972 amounted to $10 million ($36.9 million in 1998 dollars) and occurred mainly in the upstream communities of Prince George and Kamloops, and in the Surrey area of the lower Fraser Valley.

- ^ "River flooding part of Hope history". Hope Standard. June 27, 2012. Retrieved November 29, 2021.

In 1972, the Fraser River again experienced record flood waters – the second highest in recorded times with a discharge of 12,900 cubic metres per second and a maximum height of 10.141 meters at Hope on June 16. Wardle Street and part of Seventh Avenue were submerged, and on Tom Berry Road 10 houses were flooded and families were forced to evacuate their properties. Pumps were brought in to remove water and residents were able to return home after approximately a week.

- ^ "North Delta history: The historic floods of May". Surrey Now Leader. May 12, 2019. Archived from the original on November 30, 2021. Retrieved November 29, 2021.

When waters again rose in 1972, flood conditions were more reasonable controlled, with dykes, prediction and timely sandbagging. However, there was still $10 million of damage, mainly in Prince George and Surrey.

- ^ "Fraser River Floodplain". City of Surrey. December 11, 2019. Retrieved November 29, 2021.

The area flooded again in 1972 and this is why in 1975 the South Westminster Dyking District transferred to Surrey under an agreement with the province to improve the existing dyke and flood protection systems.

- ^ River Water Still Rising Archived October 6, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. Prince George Free Press, June 6, 2006.

- ^ Fraser flood alert imminent Mission gauge under close scrutiny, river likely to peak at 7.5 m by Saturday Archived September 28, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. Langley Times, June 6, 2007.

Further reading

- Boyer, David S. (July 1986). "The Untamed Fraser River". National Geographic. Vol. 170, no. 1. pp. 44–75. ISSN 0027-9358. OCLC 643483454.

- The Fraser, Bruce Hutchison, 1950, classic work by noted BC editor and publisher