Gordodon

The unique jaws and teeth of Gordodon amongst early synapsids suggest that it was one of the first herbivorous tetrapods to have specialised in selectively feeding on high nutrient, low-fibre plant fructifications (seeds and fruit-like structures). It was also one of the first tetrapods to show such specialised dentition and feeding apparatus, evolving only a few million years after the first obligate tetrapod herbivores appeared in the fossil record. Prior to the discovery of Gordodon, the earliest non-mammalian synapsid herbivores with similarly complex teeth were the mammal-like cynodonts that appeared 95 million years later during the Triassic.

Discovery and naming

The only known fossil of Gordodon was discovered in March 2013 by Ethan Schuth, a geology student of the University of Oklahoma, during a field trip. The specimen was found exposed along a road cut near the city of Alamogordo in Otero County, New Mexico, in strata identified as belonging to the base of the Bursum Formation. They contacted the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science (NMMNH) in Albuquerque, who collected the specimen during 2013–2014 and catalogued the specimen as NMMNH P-70796. While the specimen was being excavated, the skull was accidentally sawn through, leaving a vertical cut 6.25 mm across through the jaws and orbit.

A description of the specimen was published in 2018 by palaeontologists Spencer G. Lucas, Larry F. Rinehart and Matthew D. Celeskey, where it was named as the holotype of a new genus and species, Gordodon kraineri. The generic name is from the Spanish "gordo", meaning "fat", and the Ancient Greek suffix "-odon" to mean "fat tooth", referring to its characteristically large front teeth. The name is also a play on "Alamogordo", the name of the city close to where the fossil was discovered. The specific name kraineri was chosen in honour of Karl Krainer, a geologist of the University of Innsbruck in recognition of his extensive work on palaeontology and geology in New Mexico.

The only known specimen of Gordodon is an incomplete but articulated skeleton exposed mostly on its right side that consists of the front portion of the animal, including the skull and lower jaws, five cervical vertebrae in the neck, four complete dorsal vertebrae from the back and parts of the tall neural spines of 12 other vertebrae not visible on the slab, ribs, parts of both right and left scapulae and clavicles in the shoulder, and two partial digits likely from the hand. Although relatively small in size, suturing of both the vertebrae and the shoulder suggests that the specimen was not a young juvenile.

The type specimen of Gordodon was discovered stratigraphically low in the Bursum Formation, at a site Lucas and colleagues referred to as the "edaphosaur locality". This locality is only 3 m (9 ft 10 in) above the base of the formation, which has been approximately dated to the earliest North American Wolfcampian stage and typically considered to be of the Early Permian, equivalent to the globally defined Asselian stage. Gordodon straddles the boundary between the Pennsylvanian subperiod of the latest Carboniferous and the very earliest Permian at approximately 299 million years old, and may alternatively be considered Pennsylvanian in age based on alternative definitions for the base of Permian (e.g. conodont biostratigraphy). The fossil was found in fluvial facies of olive-grey sandstones deposited by river channels.

Description

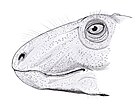

Gordodon was a relatively small edaphosaurid, with an estimated length from head to hips (presacral length) of about 1 m (3 ft 3 in), not including the tail. It is also estimated to have weighed only 34 kilograms (75 lb), less than half the size of most species of Edaphosaurus. Compared with later edaphosaurids, the ribs of Gordodon were much less curved, and so it is unlikely that Gordodon was as barrel-chested as Edaphosaurus, and instead had a much more narrow, straight-sided torso like those of the carnivorous sphenacodontids such as Dimetrodon. The vertebrae are relatively gracile, and unusually had a pair of keels on their undersides, a trait unique to Gordodon among edaphosaurids. The vertebrae themselves have relatively elongated, rectangular centra (the main body of the vertebrae) in the neck, while those of the dorsal vertebrae in the back are more square. Aside from part of the shoulder girdle, the only known limb bones of Gordodon are two incomplete digits likely from one of the hands. These digits are long and slender, with curved, pointed claws at their tips, more like those of Remigiomontanus than the stockier digits of the larger Edaphosaurus. Other aspects of the anatomy of Gordodon remain unknown, as it is only known from a single partial specimen.

Skull

The skull of Gordodon is relatively large for an edaphosaurid, measuring 159 millimetres (6.3 in) long from front to back. Although, like other edaphosaurids, the head is still proportionately small compared to its body. The skull is slightly arched upwards along its length, with a relatively long and narrow snout that is roughly equal in length to the portion of the skull behind the eyes. The orbits (eye sockets) themselves are large and rounded, with a prominent overhanging 'brow' of bone above them formed by the prefrontal, frontal and postfrontal bones. The single opening behind the eyes (the temporal fenestra, an attachment point for jaw muscles) characteristic of synapsids is roughly square-shaped and smaller than the orbit, although it is noticeably taller than it is wide.

The jaws and teeth of Gordodon are one of its most distinctive features. The only teeth at the front of the jaw are a pair of large incisor-like teeth at the tips of both upper and lower jaws. Only the upper 'incisors' are preserved, although an opposing pair on the lower jaw is inferred by an open tooth socket on the visible right dentary (the tooth bearing bone in the lower jaw). These teeth appear triangular in shape and pointed when viewed from the side, but were likely rectangular and chisel-like from the front. These are the only teeth in the premaxillae (the front-most upper jaw bones), and behind them is a long upward-curved diastema, a prominent gap in the jaws between the front and back teeth, formed by the maxilla (the main upper jaw bone). Behind the diastema there are 18 small, peg-like teeth in each maxilla, with 8 slightly larger teeth in front and 6 smaller teeth at the back (it is unclear if the transition between them was sharp or gradual due to damage to the fossil). The dentary teeth in the lower jaw are similar in size and shape to those in the upper jaw, and there is likewise an opposing diastema at the front, although it is more gently curved. Like Edaphosaurus, Gordodon had dense batteries of small, peg-like teeth on the inside surfaces of its lower jaws set on distinctive tooth plates. These likely corresponded with an opposing set on the pterygoid bones above on the roof of the mouth, although this area is not visible in the only known specimen. Very small (<1 mm across) palatal teeth are visible on the vomer (a bone in the palate), however, and they form a pair of elongated clusters along the midline of the diastema between the cheek teeth and the 'incisors'. The lower jaw is notably deeper at the back, with relatively shallow dentaries and an unfused mandibular symphysis (where the two lower jaws connect at the front) that is only weakly deflected downwards into a slight 'chin'.

Sail

Like other edaphosaurids, Gordodon possessed a large sail supported by enormously elongated neural spines on its vertebrae running down its neck and back. Intriguingly, the sail of Gordodon appears to have a transitional morphology between earlier edaphosaurids and Edaphosaurus. Unlike earlier edaphosaurids, the neural spines are thicker and laterally compressed, almost blade-like at their tips, although they are not as heavyset as those of Edaphosaurus. Further, Gordodon lacks an elongated spine on its axis (the second vertebra in the neck), unlike the earlier edaphosaurid Ianthasaurus, and so the sail only begins over its third cervical vertebra, as in Edaphosaurus. The neural spines also sport numerous bony tubercles like that of Edaphosaurus. However, they do not form organised rows of thick, generally symmetrical blunt cross-bars as seen in Edaphosaurus. Instead, the tubercles of Gordodon are thin and pointed, like thorns, and are randomly distributed across the spines asymmetrically on either side with no discernible pattern to them. Unusually, the neural spines continue to substantially increase in length down to the 12th spine, whereas in Edaphosaurus and Ianthasaurus the spine height evens out at the 8th spine. Likewise, the highest neural spine is the 16th, and so the sail peaks further back than where it does in Edaphosaurus (the 12th spine). Combined, this gives Gordodon a much more steeply sloping sail compared to the more semicircular shaped sails of both Edaphosaurus and Ianthasaurus.

Classification

Gordodon was a member of family Edaphosauridae, a group of mostly omnivorous and herbivorous sail-backed synapsids within the clade Eupelycosauria, with which it shares a characteristically small head, reduced size of the teeth along the jaw margins, a jaw joint below the tooth row, and tall neural spines with lateral protuberances. Gordodon is distinguished from all other edaphosaurids by its uniquely varied, or heterodont, teeth, namely its chisel-like 'incisors', diastema, and peg-like cheek teeth. Gordodon can also be distinguished by a relatively short suture between the nasals and maxilla, relatively gracile cervical and dorsal vertebrae with two keels along the bottom, and randomly distributed, thornlike tubercles on its neural spines.

A phylogenetic analysis was performed by Lucas and colleagues in 2018 to determine the relationships of Gordodon to other edaphosaurids. Another analysis of edaphosaurid relationships was published by Spindler and colleagues in 2019, which included additional newly described species of edaphosaurids. Both analyses found Gordodon in a similar position respective of other edaphosaurids, more derived than Ianthasaurus and Glaucosaurus but less so than Lupeosaurus and Edaphosaurus.

The cladogram of Spindler et al. (2019) is shown simplified below:

It was noted by both analyses that Gordodon helped to resolve the 'middle' portion of the edaphosaurid tree, which in previous analyses was an unstable region and the relationships between species poorly resolved. Gordodon combines traits of earlier edaphosaurids, such as longer vertebral centra and a relatively long snout, with more derived features like the numerous bony tubercles present on the neural spines. Similarly, it shows a number of intermediate traits between earlier and derived edaphosaurids, including an overall smaller skull, shortened snout length, and a deeper mandible compared to earlier edaphosaurids. The relative completeness of Gordodon allowed for comparisons to be made with earlier and derived edaphosaurids that were not known from overlapping material (e.g. skulls vs postcrania), elucidating the relationships between them.

Evolutionary history

Diastemata are found in the upper jaws of some other early synapsids, including the predatory Kenomagnathus and Tetraceratops. However, Gordodon is thus far the only herbivorous non-therapsid synapsid to possess a true diastema. Gordodon is also the only synapsid outside of cynodonts to have a dentary diastema opposing the one in the upper jaw. The mammal-like diastema and heterodont teeth of Gordodon are independently evolved from those of more derived therapsids, including mammals, and indicate that the evolution of mammalian jaws and teeth was not a linear process, with functional diastemata evolving multiple times in early synapsids, including edaphosaurids. The diastema of Gordodon likely originated from a slight gap in the upper tooth row of early edaphosaurids (an 'initial diastema') such as Ianthasaurus, formed by the overlapping attachments of the premaxilla and maxilla.

Within Edaphosauridae, Gordodon is also indicative that at least two distinct feeding styles of herbivory evolved within the family early in its evolutionary history: a specialised low-fibre diet in Gordodon; and generalised browsing of high fibre plants in more derived edaphosaurids, namely Edaphosaurus. However, it is currently unclear whether both styles descended from less specialised low-fibre herbivores, or if each evolved from a more omnivorous ancestor similar to Ianthasaurus. The earliest Permian age of Gordodon also indicates that herbivorous edaphosaurids diversified early on in their evolution, and so raises the possibility for greater ecological diversity within Edaphosauridae that is yet to be discovered.

Palaeobiology

Like other edaphosaurids, Gordodon was a herbivore, although its unique dentition suggests that it was feeding on different foods than its relatives. In its description by Lucas and colleagues in 2018, they suggested that the specialised features of its jaws and teeth indicated that Gordodon was a more selective feeder, a position agreed upon by Spindler (2020). They based this interpretation on traits such as its narrower snout, specialised 'incisors', and its diastema, that together would have allowed it to selectively crop and process vegetation into smaller pieces before swallowing them. Such traits are found in living mammals known to be selective feeders. This method of feeding could have allowed Gordodon to consume more nutrient-rich, low-fibre plant matter than other edaphosaurids, namely fructifications (non-vegetative plant tissue, e.g. seeds and fruits). While true fruits are only produced by flowering plants (angiosperms) which had not evolved yet, similar fruit-like structures are found in gymnosperms, including the fleshy seeds and cones of conifers, gnetophytes, and cycads. The relatively narrow, "slab-sided" ribcage of Gordodon may also support their interpretation, as such a low fibre diet requires less time to digest and so Gordodon would not have required a large, rounded gut for fermenting fibrous vegetation.

Gordodon was inferred by Lucas and colleagues (2018) to have used its large 'incisors' for chiselling food, similar to some modern rodents and rabbits, placing food within the diastema before being passed back to be ground up by the tooth plates. The simpler small, peg-like teeth of the maxilla and dentary functioned for cropping vegetation. The low, offset jaw joint allows for the upper and lower teeth to occlude along their entire length, giving Gordodon a stronger, more crushing bite, rather than shearing. Furthermore, the jaw joint is loosely fitting and has a rounded, spherical articulation, allowing for palinal motion of the lower jaw (where the jaw is slid backwards against the upper jaw) for further grinding and slicing of food. The 'cheek' teeth of Gordodon are not specialised for this purpose, unlike living mammals, and mastication (chewing) was likely accomplished by the tooth plates. This would be a relatively more complex form of mastication compared to the more limited palinal motion seen in the lower jaw of Edaphosaurus. However, the precise function of the diastema and motion of the jaws in relation to the tooth plates on the upper and lower jaws is difficult to determine, as noted by palaeontologist Frederik Spindler in 2020, who further suggested the role of a specialised tongue. Therefore, the exact mechanisms of the jaws and teeth during food processing of Gordodon, as well as other edaphosaurids, remains unknown.

Palaeoecology

The sedimentary facies of the Bursum Formation indicate that Gordodon inhabited a near-shore coastal plain environment. Over the course of the formation's deposition, the habitat alternated between terrestrial, beach, and marine environments over cyclical rises and falls of sea level, indicative of its proximity to the coast. Most organisms known from the Bursum Formation are marine, with particularly abundant remains of invertebrates that include a variety of gastropods, ostracods, echinoderms, brachiopods and bivalves, as well as tiny bryozoans and foraminiferans. Fragmentary remains of vertebrates from elsewhere in the formation, outside of the edaphosaur locality, include the remains of fish, aquatic temnospondyl amphibians and archeriids, herbivorous diadactomorphs and caseids, predatory sphenacodontids, and possibly other edaphosaurids.

References

- ^ Spencer G., Lucas; Rinehart, Larry; Celeskey, Matthew D. (November 2018). "The oldest specialized tetrapod herbivore: A new eupelycosaur from the Permian of New Mexico, USA". Palaeontologia Electronica. 21.3.39A (3): 1–42. doi:10.26879/899.

- ^ Krainer, K.; Vachard, D.; Lucas, S. G. (2003). "Microfacies and microfossil assemblages (smaller foraminifers, algae, pseudoalgae) of the Hueco Group and Laborcita Formation (Upper Pennsylvanian-lower Permian), south-central New Mexico, USA". Rivista Italiana di Paleontologia e Stratigrafia. 109 (1): 3–36. doi:10.13130/2039-4942/5491.

- ^ Davydov, V. I.; Glenister, B. F.; Spinosa, C.; Ritter, S. M.; Chernykh, V. V.; Wardlaw, B. R.; Snyder, W. S. (1998). "Proposal of Aidaralash as Global Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP) for base of the Permian System". Episodes. 21 (1): 11–17. doi:10.18814/epiiugs/1998/v21i1/003.

- ^ Spindler, Frederik; Voigt, Sebastian; Fischer, Jan (2019). "Edaphosauridae (Synapsida, Eupelycosauria) from Europe and their relationship to North American representatives". PalZ. 94: 125–153. doi:10.1007/s12542-019-00453-2.

- ^ Mazierski, D. M.; Reisz, R. R. (2010). "Description of a new specimen of Ianthasaurus hardestiorum (Eupelycosauria: Edaphosauridae) and a re-evaluation of edaphosaurid phylogeny". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 47 (6): 901–912. Bibcode:2010CaJES..47..901M. doi:10.1139/e10-017.

- ^ Spindler, F. (2020). "A faunivorous early sphenacodontian synapsid with a diastema". Palaeontologia Electronica. 23 (1). doi:10.26879/1023.

- ^ Spindler, F. (2019). "The skull of Tetraceratops insignis (Synapsida, Sphenacodontia)". Palaeovertebrata. 43 (1): e1. doi:10.18563/pv.43.1.e1.

- ^ Pérez-Barbería, E. J.; Gordon, I. J. (1999). "The functional relationship between feeding type and jaw and cranial morphology in ungulates". Oecologia. 118 (2): 157–165. Bibcode:1999Oecol.118..157P. doi:10.1007/s004420050714. PMID 28307690.

- ^ Lovisetto, A.; Guzzo, F.; Busatto, N.; Casadoro, G. (2013). "Gymnosperm B-sister genes may be involved in ovule/seed development and, in some species, in the growth of fleshy fruit-like structures". Annals of Botany. 112 (3): 535–544. doi:10.1093/aob/mct124. PMC 3718214. PMID 23761686.

- ^ Hall, J. A.; Walter, G. H. (2014). "Relative Seed and Fruit Toxicity of the Australian Cycads Macrozamia miquelii and Cycas ophiolitica: Further Evidence for a Megafaunal Seed Dispersal Syndrome in Cycads, and Its Possible Antiquity". Journal of Chemical Ecology. 40 (8): 860–868. doi:10.1007/s10886-014-0490-5. PMID 25172315.

- ^ Reisz, Robert R. (2006). "Origin of dental occlusion in tetrapods: Signal for terrestrial vertebrate evolution?". Journal of Experimental Zoology Part B: Molecular and Developmental Evolution. 306B (3): 261–277. doi:10.1002/jez.b.21115. PMID 16683226.

- ^ Krainer, K.; Lucas, S. G. (2013). "The Pennsylvanian–Permian Bursum Formation in central New Mexico". The Carboniferous–Permian Transition in Central New Mexico: New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, Bulletin. 59: 143–160.

- ^ Harris, S. K.; Lucas, S. G.; Berman, D. S.; Henrici, A. C. (2004). "Vertebrate fossil assemblage from the Upper Pennsylvanian Red tanks member of the Bursum Formation, Lucero uplift, central New Mexico". Carboniferous-Permian Transition at Carrizo Arroyo, Central New Mexico: New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, Bulletin. 25: 267–283.

External links

Media related to Gordodon at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Gordodon at Wikimedia Commons