Hoba Meteorite

Impact

The Hoba meteorite is thought to have impacted Earth less than 80,000 years ago. It is inferred that the Earth's atmosphere slowed the object in such a way that it impacted the surface at terminal velocity, thereby remaining intact and causing little excavation (expulsion of earth). Assuming a drag coefficient of about 1.3, the meteor appears to have slowed to about 2.75 km/s (6140 mph) from an entry speed to the atmosphere typically in excess of 10 km/s (22,370 mph). The meteorite is unusual in that it is flat on both major surfaces.

Alternatively since this region was glaciated during the fall window, the impact crater may have been limited to the ice.

Discovery

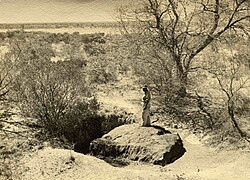

The Hoba meteorite left no preserved crater and its discovery was a chance event. In 1920, the owner of the land, Jacobus Hermanus Brits, encountered the object while ploughing one of his fields with an ox. While working the field, he heard a loud metallic scratching sound and the plough came to an abrupt halt. The obstruction was excavated, identified as a meteorite and described by Mr. Brits, whose report was published in 1920 and can be viewed at the Grootfontein Museum in Namibia.

Friedrich Wilhelm Kegel took the first published photograph of the Hoba meteorite.

Description and composition

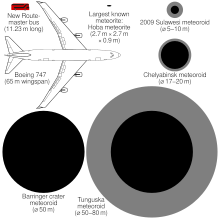

Hoba is a tabular body of metal, measuring 2.7×2.7×0.9 m (8 ft 10 in×8 ft 10 in×2 ft 11 in). In 1920, its mass was estimated at 66 tonnes. Erosion, scientific sampling and vandalism reduced its bulk over the years. The remaining mass is estimated at just over 64 tonnes. The meteorite is composed of about 84% iron and 16% nickel, with traces of cobalt. It is classified as an ataxite iron meteorite belonging to the nickel-rich chemical class IVB. A crust of iron hydroxides is present on the surface due to weathering oxidation.

Modern history

In an effort to control relocation attempts, with permission from the farm owner, Mrs O Scheel, on March 15, 1955, the government of South West Africa (now Namibia) declared the Hoba meteorite to be a national monument. Since 1979 the proclamation has been extended to an area of 425 m².

From about the 1970s, development of the meteorite site for tourism was hampered by its location in the Otavi triangle of Otavi, Tsumeb and Grootfontein, a key arena of the Namibian war of independence or South African Border War. The war and liberation struggle ended with the 1988 Tripartite Accord. General elections under universal franchise in 1989 led to formation of the independent Republic of Namibia in 1990.

In 1987, the farm owner donated the meteorite and the site where it lies to the state for educational purposes. Later that year, the government opened a tourist centre at the site. As a result of these developments, vandalism of the Hoba meteorite has ceased and it is now visited by thousands of tourists every year.

Nevertheless, specimens sourced from earlier theft and vandalism continue to be traded. On the 7th of December 2021, an unusually large 2.8 kg specimen, illegally harvested in 1968, was sold for $59,062 in Los Angeles by international auction house Bonhams. The Bonhams sale notice states: "The present specimen was obtained in 1968 by the father of the present owner when he visited the main mass of Hoba together with some friends. Using a hand saw, they cut a large block of the meteorite from the main mass 'as a souvenir', an activity which took them between three and four hours."

-

Hoba meteorite in the 1950s, illustrating its remote and unprotected location

-

A woman sitting on the meteorite in 1967

-

A 166 kg (365 lb) meteorite at the National Trust's Tatton Park, previously incorrectly labelled as Hoba, identified as Gibeon

See also

Notes and references

- ^ Meteoritical Bulletin Database: Hoba

- ^ McSween, Harry (1999). Meteorites and their parent planets (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521583039. OCLC 39210190.

- ^ Cassidy, Joseph (2009). Place Names of Namibia A Historical Dictionary. Windhoek: Macmillan Education Namibia Publishers (Pty) Ltd. p. 37. ISBN 978-99916-0-654-5.

- ^ Field Guide to Meteors and Meteorites O. Richard Norton and Lawrence Chitwood. Springer Science + Business Media 2008, ISBN 978-1-84800-156-5

- ^ Spencer, L. J.; Hey, M. H. (March 1932). "Hoba (South-West Africa), the largest known meteorite" (PDF). Mineralogical Magazine and Journal of the Mineralogical Society. XXIII (136): 4. Bibcode:1932MinM...23....1S. doi:10.1180/minmag.1932.023.136.03. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-12-15.

- ^ Comerford, M.F. (September 1967). "Comparative erosion rates of stone and iron meteorites under small-particle bombardment". Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 31 (9). Elsevier Science, New York: 1470. Bibcode:1967GeCoA..31.1457C. doi:10.1016/0016-7037(67)90021-X. ISSN 0016-7037.

- ^ Voigt, Andreas (2004). National Monuments in Namibia: An Inventory of Proclaimed National Monuments in the Republic of Namibia. Gamsberg Macmillan. pp. 4–5. ISBN 9991605932.

- ^ Lelyveld, Joseph (August 1982). "Inside Namibia". The New York Times.

- ^ "Bonhams : HOBA IRON METEORITE--A CUT BLOCK OF TRIANGULAR, PRISMATIC FORM".

- ^ "Meteorite 1303720".

Further reading

- Universe: The Definitive Visual Dictionary, Robert Dinwiddie, DK Adult Publishing, (2005), pg. 223.

- Spargo, P. E. (2008). "The History of the Hoba Meteorite Part I: Nature and Discovery" (PDF). Monthly Notes of the Astronomical Society of Southern Africa. 67 (5/6): 85–94. Bibcode:2008MNSSA..67...85S. Retrieved 2018-07-24.

- Spargo, P. E. (2008). "The History of the Hoba Meteorite Part II: The News Spreads" (PDF). Monthly Notes of the Astronomical Society of Southern Africa. 67 (9/10): 166–177. Bibcode:2008MNSSA..67..166S. Retrieved 2018-07-24.

- Spargo, P. E. (2008). "The History of the Hoba Meteorite Part III: Known and Loved by All" (PDF). Monthly Notes of the Astronomical Society of Southern Africa. 67 (11/12): 202–211. Bibcode:2008MNSSA..67..202S. Retrieved 2018-07-24.

![A 166 kg (365 lb) meteorite at the National Trust's Tatton Park, previously incorrectly labelled as Hoba, identified as Gibeon[10]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/09/Tatton_Park_2016_205_%284x3%29.jpg/240px-Tatton_Park_2016_205_%284x3%29.jpg)