Indigenous People Of Mexico

- 865,972 people monolingual in an indigenous language (0.6%)

- 7,364,645 people who speak an indigenous language (Including bilinguals in Spanish.) (6.1%)

Indigenous peoples of Mexico (Spanish: gente indígena de México, pueblos indígenas de México), Native Mexicans (Spanish: nativos mexicanos) or Mexican Native Americans (Spanish: pueblos originarios de México, lit. 'Original Peoples of Mexico'), are those who are part of communities that trace their roots back to populations and communities that existed in what is now Mexico before the arrival of Europeans.

The number of indigenous Mexicans is defined through the second article of the Mexican Constitution. The Mexican census does not classify individuals by race, using the cultural-ethnicity of indigenous communities that preserve their indigenous languages, traditions, beliefs, and cultures. As a result, the count of indigenous peoples in Mexico does not include those of mixed indigenous and European heritage who have not preserved their indigenous cultural practices. Genetic studies have found that most Mexicans are of partial indigenous heritage. According to the National Indigenous Institute (INI) and the National Institute of Indigenous Peoples (CDI), in 2012 the indigenous population was approximately 15 million people, divided into 68 ethnic groups. The 2020 Censo General de Población y Vivienda reported 11,132,562 people living in households where someone speaks an indigenous language, and 23,232,391 people who were identified as indigenous based on self-identification.

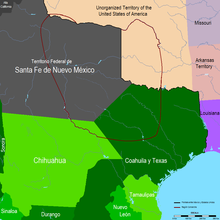

The indigenous population is distributed throughout the territory of Mexico but is especially concentrated in the Sierra Madre del Sur, the Yucatán Peninsula, the Sierra Madre Oriental, the Sierra Madre Occidental, and neighboring areas. The states with the largest indigenous population are Oaxaca and Yucatán, both having indigenous majorities, with the former having the highest percentage of indigenous population. Since the Spanish colonization, the North and Bajio regions of Mexico have had lower percentages of indigenous peoples, but some notable groups include the Rarámuri, the Tepehuán, the Yaquis, and the Yoreme.

Definition

In the second article of the Mexican Constitution, Mexico defines itself as a pluricultural nation in recognition of the diverse ethnic groups that constitute it and where the indigenous peoples are the original foundation. The number of indigenous Mexicans is measured using constitutional criteria.

The category of indigena (indigenous) can be defined narrowly according to linguistic criteria including only persons that speak one of Mexico's 89 indigenous languages, this is the categorization used by the National Mexican Institute of Statistics. It can also be defined broadly to include all persons who self-identify as having an indigenous cultural background, whether or not they speak the language of the indigenous group they identify with. This means that the percentage of the Mexican population defined as "indigenous" varies according to the definition applied; cultural activists have referred to the usage of the narrow definition of the term for census purposes as "statistical genocide".

The indigenous peoples in Mexico have the right of free determination under the second article of the constitution. According to this article, indigenous peoples are granted:

- the right to decide the internal forms of social, economic, political, and cultural organization;

- the right to apply their own normative systems of regulation as long as human rights and gender equality are respected;

- the right to preserve and enrich their languages and cultures;

- the right to elect representatives before the municipal council where their territories are located;

The Law of Linguistic Rights of the Indigenous Languages recognizes 89 indigenous languages as national languages, which have the same validity as Spanish in all territories where they are spoken. According to the National Institute of Statistics, Geography and Data Processing (INEGI), approximately 5.4% of the population speaks an indigenous language. The recognition of indigenous languages and the protection of indigenous cultures is granted not only to the ethnic groups indigenous to modern-day Mexican territory but also to other North American indigenous groups that migrated to Mexico from the United States in the nineteenth century and those who immigrated from Guatemala in the 1980s.

History

Pre-Columbian civilizations

The prehispanic civilizations of what now is known as Mexico are often divided into two regions: Mesoamerica, the cultural area where several complex civilizations developed before the arrival of the Spanish in the sixteenth century, and Aridoamerica (or simply "The North"), the arid region north of the Tropic of Cancer which was less densely populated. Despite the conditions, the Mogollon culture and peoples established urban population centers at Casas Grandes and Cuarenta Casas in a vast territory that encompassed northern Chihuahua state and parts of Arizona and New Mexico in the United States.

Mesoamerica was densely populated by diverse indigenous ethnic groups which, although sharing common cultural characteristics, spoke different languages and developed unique civilizations.

One of the most influential civilizations in Mesoamerica was the Olmec civilization, sometimes referred to as the "Mother Culture of Mesoamerica". The later civilization in Teotihuacan reached its peak around 600 AD when the city possibly became the sixth largest city in the world, whose cultural and theological systems influenced the Toltec and Aztec civilizations in later centuries. Evidence has been found on the existence of polyethnic communities or neighborhoods in Teotihuacan (and other large urban areas like Tenochtitlan).

The Maya civilization, influenced by other Mesoamerican civilizations, developed a vast cultural region in southeast Mexico and northern Central America, while the Zapotec and Mixtec cultures dominated the valley of Oaxaca and the Purépecha in western Mexico.

Trade

Scholars agree that significant systems of trading existed between the cultures of Mesoamerica, Aridoamerica and the American Southwest, and the architectural remains and artifacts share a commonality of knowledge attributed to this trade network. The routes stretched far into Mesoamerica and reached as far north as ancient communities that included such population centers in the United States such as Snaketown, Chaco Canyon, and Ridge Ruin near Flagstaff (considered some of the finest artifacts ever located).

Colonial era

By the time of the arrival of the Spanish in central Mexico, many peoples of Mesoamerica (with the notable exception of the Tlaxcaltecs and the Purépecha Kingdom of Michoacán) were loosely joined under the Aztec Empire, the last Nahua civilization to flourish in Central Mexico. The capital of the empire, Tenochtitlan, became one of the largest urban centers in the world, with an estimated population of 350,000 inhabitants.

During the conquest of the Aztec Empire, the Spanish conquistadors allied with other ethnic groups in the region, including the Tlaxcaltecs. This strategy succeeded due to discontent with Aztec rule, which demanded tributes and used conquered peoples for ritual sacrifice. During the following decades, the Spanish consolidated their rule in what became the viceroyalty of New Spain. Through the Valladolid Debate, the crown recognized the indigenous nobility in Mesoamerica as nobles, freed indigenous slaves, and kept the existing basic structure of indigenous city-states. Indigenous communities were incorporated as communities under Spanish rule.

As part of the Spanish incorporation of indigenous into the colonial system, the friars taught indigenous scribes to write their languages in Latin letters so that there is a large corpus of colonial-era documentation in the Nahuatl language, Mixtec, Zapotec, Yucatec Maya, and others. Such a written tradition likely took hold through existing practices of pictorial writing found in many indigenous codices. New Philology scholars have utilized the colonial-era alphabetic documentation to illuminate the colonial experience of Mesoamerican peoples from their own viewpoints.

Conquerors awarded labor and tribute under the encomienda system benefitted financially. Since Mesoamerican peoples had existing requirements of labor duty and tribute in the pre-conquest era, indigenous officials were involved in maintaining this system in their communities. There was a precipitous decline in indigenous populations, mainly due to the spread of European diseases previously unknown in the America but also through war and forced labor. Pandemics wrought havoc, but indigenous communities recovered with fewer members.

With contact between indigenous populations, Spaniards, African slaves, and starting in the late sixteenth century, Asian slaves (chinos) brought as goods the trade via the Manila Galleon there was an intermingling of groups, with mixed-race castas, particularly mestizos, becoming a component of Spanish cities and to a lesser extent indigenous communities. The Spanish legal structure formally separated what they called the República de Indios (the republic of Indians) from the República de Españoles (Republic of Spaniards), with the latter encompassing all those in the Hispanic sphere: Spaniards, Africans, and mixed-race castas. Although Indigenous peoples were marginalized in the colonial system, and often rebelled, the paternalistic structure of colonial rule supported the continued existence and structure of indigenous communities. The Spanish crown recognized the existing ruling group, gave protection to the land holdings of indigenous communities, and communities and individuals had access to the Spanish legal system. However, these codes were often ignored in practice, and racial discrimination was prevalent in New Spain.

In the religious sphere, indigenous men were banned from Christian priesthood, following an early Franciscan attempt that included fray Bernardino de Sahagún to train an indigenous group. Mendicants of the Franciscan, Dominican, and Augustinian orders initially evangelized indigenous in their own communities in what is often called the "spiritual conquest". On the northern frontiers, the Spanish created missions and settled Indigenous populations in these complexes, which prompted raids from those who resisted settlement (given the name Indios Bárbaros). The Jesuits were prominent in this enterprise until their expulsion from Spanish America in 1767. Catholicism, often with local characteristics, was the only permissible religion in the colonial era.

Indigenous land

During the early colonial era in central Mexico, Spaniards were more interested in access to indigenous labor than land ownership. The institution of the encomienda, a crown grant of the labor of indigenous communities to conquerors was a key element of the imposition of Spanish rule. The Spanish crown initially maintained the indigenous sociopolitical system of local rulers and land tenure, with the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire eliminating the superstructure of rule, and replacing it with Spanish.

The crown had several concerns about the encomienda. First was that the holders of encomiendas, called encomenderos, were becoming too powerful, essentially a seigneurial group that might challenge crown power (as shown in the conspiracy by conqueror Hernán Cortés's legitimate son and heir). The second was that the encomenderos were monopolizing indigenous labor, excluding newly arriving Spaniards. And third, the crown was concerned about the damage to the indigenous vassals and their communities by the institution. Through the New Laws of 1542, the crown sought to phase out the encomienda and replace it with another crown mechanism of forced indigenous labor, the repartimiento. Indigenous labor was no longer monopolized by a small group of conquerors and their descendants but apportioned to a larger group of Spaniards. Through the repartimiento, indigenous peoples were obligated to perform low-paid labor for a certain number of weeks or months on Spanish enterprises, notably silver mining.

The land of indigenous peoples is used for material reasons as well as spiritual reasons. Religious, cultural, social, spiritual, and other events relating to their identity are also tied to the land. Indigenous people use collective property so that the aforementioned services that the land provides are available to the entire community and future generations. This was a stark contrast to the viewpoints of colonists that saw the land purely in an economic way where land could be transferred between individuals. Once the land of the indigenous people and therefore their livelihood was taken from them, they became dependent on those that had land and power. Additionally, the spiritual services that the land provided were no longer available and caused a deterioration of indigenous groups and cultures.

Colonial-era racial categories

The Spanish legal system divided racial groups into two basic categories, the República de Españoles, consisting of all non-indigenous, but initially Spaniards and black Africans, and the República de Indios.

The degree to which racial category labels had legal and social consequences has been subject to academic debate since the idea of a "caste system" was developed by Ángel Rosenblat and Gonzalo Aguirre Beltrán in the 1940s. Both historians popularized the notion that racial status was a key organizing principle of Spanish colonial rule. However, recent academic studies have challenged this notion, considering it a flawed and ideologically based reinterpretation of the colonial period.

When Mexico gained independence in 1821, the casta designations were eliminated as a legal structure, but racial divides remained. White Mexicans argued about what the solution was to the "Indian Problem", that is indigenous who continued to live in communities and were not integrated politically or socially as citizens of the new republic. The Mexican Constitution of 1824 has several articles pertaining to indigenous peoples.

Independence to the Mexican Revolution

The Mexican War of Independence was a decade-long struggle ending in 1821, in which indigenous peoples participated for their own motivations. The new country was named after its capital city, Mexico City. The new flag had at its center a symbol of the Aztecs, an eagle perched on a nopal cactus. Mexico declared the abolition of slavery in 1829 and the equality of all citizens before the law in 1857. Indigenous communities continued to have rights as corporations to maintain land holdings until the liberal Reforma. Some indigenous individuals integrated into Mexican society, like Benito Juárez of Zapotec ethnicity, the first indigenous president in the Americas. Juárez supported the removal of provisions protecting indigenous communal land holdings through the Lerdo law.

In the North of Mexico, indigenous peoples, such as the Comanche and Apache, who had acquired the horse, waged a successful warfare against the Mexican state. The Comanche controlled considerable territory, called the Comancheria. The Yaqui also had a long tradition of resistance, with the late nineteenth-century leader Cajemé being prominent during the Yaqui Wars. The Mayo joined their Yaqui neighbors in rebellion after 1867. In Yucatán, Mayas waged a protracted war against local Mexican control in the Caste War of Yucatán, which was most intensely fought in 1847 and lasted until 1915.

20th century

The Mexican Revolution, a violent social and cultural movement that defined 20th-century Mexico, produced a nationalist sentiment that the indigenous peoples were the foundation of Mexican society in a movement known as indigenismo. Several prominent artists promoted the "Indigenous Sentiment" (sentimiento indigenista) of the country, including Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera. Throughout the twentieth century, the government established bilingual education in some indigenous communities and published free bilingual textbooks. Some states of the federation appropriated an indigenous inheritance in order to reinforce their identity.

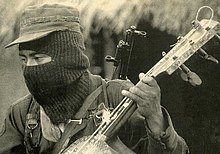

In spite of the official recognition of indigenous peoples, the economic underdevelopment of their communities, accentuated by the crises of the 1980s and 1990s, has not allowed for the development of most indigenous communities. Thousands of indigenous Mexicans have emigrated to urban centers in Mexico and the United States. In Los Angeles, for example, the Mexican government has established electronic access to some of the consular services provided in Spanish as well as Zapotec and Mixe. Some of the Maya peoples of Chiapas have revolted, demanding better social and economic opportunities, requests voiced by the EZLN.

The Chiapas conflict of 1994 led to collaboration between the Mexican government and the Zapatista Army of National Liberation, a libertarian socialist indigenous political group. This movement generated international media attention and united many indigenous groups. In 1996 the San Andrés Larráinzar Accords were negotiated between the Zapatista Army of National Liberation and the Mexican government. The San Andrés accords were the first time that indigenous rights were acknowledged by the Mexican government.

The government has made certain legislative changes to promote the development of rural and indigenous communities and the promotion of indigenous languages. The second article of the Constitution was modified to include the right of self-determination and requires state governments to promote and ensure the economic development of indigenous communities as well as the preservation of their languages and traditions.

Rights

Constitutional

The Spanish crown had legal protections for indigenous individuals as well as their communities, including establishing a separate General Indian Court. The mid-nineteenth-century liberal reform removed them as part of its establishment of equality before the law. The creation of a national identity not linked to racial or ethnic identity was an aim of Mexican liberalism.

In the late twentieth century, there has been a push for indigenous rights and a recognition of indigenous cultural identity. According to the constitutional reform of 2001, the following rights of indigenous peoples are recognized:

- acknowledgment as indigenous communities, right to self-ascription, and the application of their own regulatory systems

- preservation of their cultural identity, land, consultation, and participation

- access to the jurisdiction to the state and to development

- recognition of indigenous peoples and communities as a subject of public law

- self-determination and self-autonomy

- remunicipalization for the advancement of indigenous communities

- administer own forms of communication and media

The second article of the Constitution of Mexico recognizes and enforces the right of indigenous peoples and communities to self-determination and autonomy to:

V. Preserve and improve their habitat as well as preserve the integrity of their lands in accordance with this constitution. VI. Be entitled to the estate and land property modalities established by this constitution and its derived legislation, to all private property rights and communal property rights as well as to use and enjoy in a preferential way all the natural resources located at the places which the communities live in, except those defined as strategic areas according to the constitution. The communities shall be authorized to associate with each other in order to achieve such goals.

Through the land reforms of the early 20th century, some indigenous people had land rights under the ejido system. Under ejidos, indigenous communities have usufruct rights of the land. Indigenous communities do this when they do not have the legal evidence to claim the land. In 1992, free market reforms allowed ejidos to be partitioned and sold. For this to happen, the PROCEDE program was established. The PROCEDE program surveyed, mapped, and verified the ejido lands. According to several analysts, the privatization of ejidos has undermined the economic base of indigenous communities.

Linguistic

The history of linguistic rights in Mexico began when the Spanish first made contact with Indigenous Languages during the colonial period. Beginning in the early sixteenth century, mestizaje, the mixing of races and cultures, led to the mixing of languages as well. The Spanish Crown proclaimed Spanish to be the language of the empire; indigenous languages were used during the conversion of individuals to Catholicism. Because of this, indigenous languages were more widespread than Spanish from 1523 to 1581. During the late sixteenth century, the prevalence of the Spanish language increased.

Indigenous tongues are discriminated against and seen as not modern. By the seventeenth century, the elite minority were Spanish speakers. After independence in 1821, there was a shift to Spanish to legitimize the Mexican Spanish created by Mexican criollos. The nineteenth century brought with it programs to provide bilingual education at primary levels where they would eventually transition to Spanish-only education. Linguistic uniformity was sought out to strengthen national identity. This further excluded indigenous languages from power structures.

The Chiapas conflict of 1994 led to collaboration between the Mexican government and the Zapatista Army of National Liberation, an indigenous political group. In 1996 the San Andrés Larráinzar Accords were negotiated between the Zapatista Army of National Liberation and the Mexican government. The San Andrés accords were the first time that indigenous rights were acknowledged by the Mexican government. The San Andrés Accords did not explicitly state language but language was involved in matters involving culture and education.

In 2001, the second article of the constitution of Mexico was changed to recognize and enforce the right of indigenous peoples and communities to self-determination and therefore their autonomy to preserve and enrich their language, knowledge, and every part of their culture and identity.

In 2003, the General Law of Linguistic Rights of the Indigenous Peoples explicitly stated the protection of individual and collective linguistic rights of indigenous peoples. The final section also sanctioned the creation of a National Institute for Indigenous Languages (INALI) whose purpose is to promote the growth of indigenous languages in Mexico.

There has been a lack of enforcement of the law. For example, the General Law on Linguistic Rights of Indigenous People guarantees the right to a trial in the language of indigenous peoples with someone who understands their culture. According to the Mexican National Human Rights Commission, Mexico has not abided by this law. Examples include Jacinta Francisca Marcial, an indigenous woman imprisoned for her alleged involvement in a 2006 kidnapping. After three years and the assistance of Amnesty International, she was released for lack of evidence.

Additionally, the General Law on Linguistics also guarantees bilingual and intercultural education. These efforts have been criticized on grounds that teachers do not know the indigenous language or do not prioritize its teaching. In fact, some studies argue that formal education has decreased the prevalence of indigenous languages. Some parents do not teach their children their indigenous language, and some children refuse to learn their indigenous language for fear of discrimination. Scholars argue that there needs to be a social change to elevate the status of indigenous languages in order for the law to be withheld so that indigenous languages are protected.