Invasion Of Dominica (1778)

Early on 7 September 1778, French forces landed on the southeastern coast of the island. They rapidly took over some of the island's defenses, and eventually gained control of the high ground overlooking the island's capital, Roseau. Lieutenant Governor William Stuart then surrendered the remaining forces. Dominica remained in French hands until the end of the war, when it was returned to British control.

Background

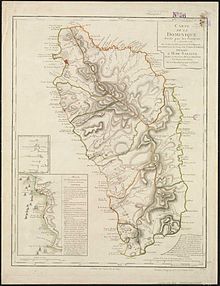

Following the pivotal Battles of Saratoga in October 1777 and the ensuing surrender of British General John Burgoyne's army, France decided to openly enter the American War of Independence as an ally of the young United States of America. France's objectives in entering the war included the recovery of territories that had been lost to Britain in the Seven Years' War. One key territory that was of particular interest was the West Indies island of Dominica, which lay between French-held Martinique and Guadeloupe, and had been captured by Britain in 1761. Recapture of the island would improve communication among the islands, and deny the use of Dominican ports to privateers who preyed on French shipping.

On Dominica, Governor Thomas Shirley had been concerned about the island's security since the war began in 1775. Operating against instructions from colonial authorities in London to minimize expenses for defence, he had pushed forward the improvement of a fort at Cachacrou and other sites. This work was incomplete when Shirley took leave in June 1778, sailing for England. Command was left with Lieutenant Governor William Stuart, and work to improve the defenses was still incomplete in August 1778, when François Claude Amour, marquis de Bouillé, the governor of the French West Indies, received word that war had been declared.

Prelude

The French frigate Concorde reached Martinique on 17 August with orders from Paris to take Dominica at the earliest opportunity, and de Bouillé made immediate plans for such an operation. He had maintained contacts in the Dominican population, which was dominated by ethnic French, including free people of color, during the years of British administration. As a result, he had an accurate picture of the condition of the Dominican defences, and knew that the island's garrison numbered fewer than "fifty soldiers fit for duty". He was also concerned with the whereabouts of the British Leeward Islands fleet of Admiral Samuel Barrington, which was significantly more powerful than his own. Unbeknownst to de Bouillé, Barrington, who had only recently assumed his post, was under orders to retain most of his fleet at Barbados until receiving further instructions. The British regular forces on the island, which in total numbered about 100, were distributed among defences in the capital Roseau, the hills that overlooked it, and at Cachacrou.

De Bouillé carefully maintained a facade of peace in his dealings with Dominican authorities while he began preparing his forces on Martinique. On 2 September he and Stuart signed an agreement that formally prohibited privateering crews from plundering. The next day de Bouillé sent one of his officers to Dominica to see whether a Royal Navy frigate was still anchored in Prince Rupert's Bay (near present-day Portsmouth). Stuart, suspicious of the man, had him questioned and then released. On 5 September de Bouillé was informed that the frigate had sailed for Barbados.

He immediately acted to launch his invasion. Some Frenchmen (some British sources suggest they were French soldiers infiltrated onto the island) gained entry to the battery at Cachacrou that evening, plied its garrison with drink, and poured sand into the touchholes of the fort's cannons, temporarily rendering them useless. De Bouillé had infiltrated some agents onto the island who had convinced some of the local French-speaking militia to abandon their duties when called up.

Invasion

After sunset on 6 September, 1,800 French troops and 1,000 volunteers departed Martinique aboard the frigates Tourterelle, Diligente, and Amphitrite, the corvette Étourdie, and a flotilla of smaller vessels. (Sources describing the action give significantly varying numbers for the size of the French force. The numbers here are from de Bouillé's report of the action; some British sources claim his force numbered as many as 4,500.) The first point of attack was the battery at Cachacrou, where the British garrison, befuddled by drink and with inoperative cannons, was overcome without significant resistance around dawn on 7 September. Two of the 48th Regiment's soldiers were driven over the ramparts and fell to their deaths. After securing the battery the French fired cannons and sent signal rockets skyward to signal their allies. These actions also alerted Stuart at Roseau, and the alarm was immediately raised. Many of the French Dominican militia failed to muster, as arranged. About 100 militia ended up mustering for duty, and were deployed among Roseau's defences.

The French proceeded to land more troops between Cachacrou and Roseau, with the objective of gaining the high ground above the capital. The main force of 1,400 men was landed about 2 miles (3.2 km) south of Roseau near Pointe Michel, with heavy fire from the hill batteries resulting in 40 casualties. De Bouillé landed with another 600 at Loubiere, between Pointe Michel and Roseau, while another 500 landed north of Roseau, and the fleet's frigates moved to bombard Roseau's defences. The French briefly captured the coastal fort at Loubiere, but were three times driven out by fire from above. They ended up withdrawing until forces were able to reach and capture the hill batteries. By noon, the French occupied the high ground above the capital, and Stuart realized the situation was hopeless.

Negotiations followed, and Stuart and de Bouillé signed the terms of capitulation at about 3:00 pm. The proceedings were interrupted by one of the French frigates, whose captain, apparently unaware of the proceedings, fired on Fort Young, where the British flag was still flying. The two commanders rushed to the fort to prevent further exchanges of gunfire before they completed the agreement. The French then formally took control of Roseau. The British regulars were made prisoners of war, and the militia were released to return home. De Bouillé, who was interested in keeping on good terms with the population, did not allow his troops to plunder the town. Instead, he levied a fee of £4,400 on the island's population that was distributed among his men.

Aftermath

De Bouillé in official correspondence claimed the French suffered no casualties. Stuart reported that the French appeared to be concealing the casualties that occurred during the invasion. De Bouillé left a garrison of 800 (700 French regulars and 100 gens de couleur libres militia) on the island, turned its command over to the Marquis de Duchilleau, and returned to Martinique.

News of Dominica's fall was received with surprise in London. Considering a single ship of the line might have prevented the attack, Admiral Barrington was widely blamed for the loss, and criticized for adhering too closely to his orders. The orders and reinforcements, whose late arrival had held Barrington at Barbados, were to launch an attack on St. Lucia. He conducted this campaign in December 1778, taking St. Lucia. These events were the first in a series of military actions resulting in the change of control of Caribbean islands during the war, in which de Bouillé was often involved. The British appointed Thomas Shirley as Governor of the Leeward Islands in 1781. He was taken prisoner by de Bouillé in the 1782 British surrender of Saint Kitts.

Dominica remained in French hands until 1784. Much to de Bouillé's annoyance, it was returned to British control under the terms of the 1783 Treaty of Paris. The fact that the French had supplied natives and mixed-blood locals with arms during the invasion caused problems for the British. These local forces, who were previously somewhat pacifist, resisted British attempts to expand their holdings on the island, leading to expanded conflict in 1785.

Notes

- ^ Boromé, p. 39

- ^ Boromé, p. 36

- ^ Boromé, pp. 36–37

- ^ Boromé, p. 37

- ^ Mahan, p. 427

- ^ Atwood, p. 109

- ^ Boromé, p. 38

- ^ Marley, p. 488

- ^ Atwood, p. 116

- ^ Atwood, p. 118

- ^ Atwood, pp. 118–119

- ^ Atwood, pp. 122–123

- ^ Boromé, p. 40

- ^ Boromé, p. 41

- ^ Mackesy, pp. 230–232

- ^ Marley, pp. 489–521

- ^ Sugden, pp. 282–283

- ^ Marley, p. 521

- ^ Boromé, p. 57

- ^ Craton, pp. 143–144

References

- Atwood, Thomas (1971) [1791]. The History of the Island of Dominica. London: Frank Cass. ISBN 978-0-7146-1929-3. OCLC 316466.

- Boromé, Joseph (January 1969). "Dominica during French Occupation, 1778–1784". The English Historical Review. 884 (330): 36–58. doi:10.1093/ehr/LXXXIV.CCCXXX.36. JSTOR 562321.

- Craton, Michael (2009) [1982]. Testing the Chains: Resistance to Slavery in the British West Indies. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-1252-3. OCLC 8765752.

- Mahan, Alfred Thayer (1898). Major Operations of the Royal Navy, 1762–1783: Being Chapter XXXI in The Royal Navy. A History. Boston: Little, Brown. OCLC 46778589.

- Mackesy, Piers (1993) [1964]. The War For America: 1775–1783. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-8192-9. OCLC 26851403.

- Marley, David F (1998). Wars of the Americas: A Chronology of Armed Conflict in the New World, 1492 to the Present. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-100-8. OCLC 166373121.

- Sugden, John (2005). Nelson: A Dream of Glory, 1758–1797. New York: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-8050-7757-5. OCLC 149424913.