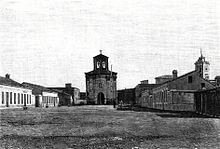

Isla De Isabel II

Name

The name of the island comes from Isabella II, Queen of Spain from 1833 to 1868.

Geography

Displaying a rounded shape, it has a total area of 0.153 square kilometres (0.059 sq mi). Substantially flatter than the Isla del Congreso, it reaches a maximum height of 35 metres above sea level.

History

Archeological remains found in the island suggest the existence of an outpost intended for sheltering ships by the 1st century BC, a time when the North-African coastline thrived during the reign of Juba II.

Along with the other two islands of the archipelago (Isla del Rey and Isla del Congreso), it was occupied in 1848 by Spain, that alleged terra nullius, anticipating French intentions to do the same from Algeria. General Francisco Serrano took possession of the islands bringing two ships from Málaga.

The work of conditioning the island of Isabel II suffered a major setback after the passing of a strong storm in March 1849. Then the question arose of whether the stay in the archipelago was worth it or not.

Between 1910 and 1915 the island was connected through a dike with the Isla del Rey.

Electric lighting was installed on the island in 1922.

Population

The island is the only inhabited island of the archipelago. It currently hosts a military garrison with personnel from the Ministry of Environment of Spain, as the islands are a National Reserve protected because of the wealth of their natural species.

References

Citations

- ^ Alamán, Lucas (1853). Diccionario universal de historia y de geografía. Librería de Andrade. p. 166.

- ^ Pineda & Barrera 2013, p. 10.

- ^ Calderon, Cruz & Ruggeri 2018, p. 85.

- ^ Aragón Gómez 2013, p. 141.

- ^ Andrews, George Frederick (1911). "Spanish Interests in Morocco". American Political Science Review. 5 (4): 553–565. doi:10.2307/1945023. ISSN 0003-0554.

- ^ Jiménez García-Carriazo 2018, p. 216.

- ^ Madariaga 2012.

- ^ Cal, Juan Carlos de la; Ruiz, Sara (14 July 2002). "Las otras "perejiles"". El Mundo.

- ^ Esquembri Hinojo 2013a, pp. 194–195.

- ^ Esquembri Hinojo 2013a, p. 196.

- ^ Escámez Pastrana 1989, p. 47.

- ^ Esquembri Hinojo 2013b, p. 22.

Bibliography

- Aragón Gómez, Manuel (2013). "De las tres ínsulas a Jafarín. Las Islas Chafarinas y su entorno en la Antigüedad y Medievo" (PDF). Aldaba (37): 125–156. ISSN 0213-7925.

- Calderon, F.J.; Cruz, Elena; Ruggeri, G. (2018). "The Chafarinas Islands: Borders, Environmental Protection and Sustainable Tourism". In Calò, Patrizia; Ruggieri, Giovanni (eds.). Book of Full Papers - OTIE ICIT 2018 (PDF). pp. 83–98. ISBN 978-88-943724-1-0.

- Escámez Pastrana, Antonio Manuel (1989). "Las Islas Chafarinas y su problemática medio ambiental" (PDF). Aldaba (13). Melilla: Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia: 45–69. doi:10.5944/aldaba.13.1989.20153. ISSN 0213-7925.

- Esquembri Hinojo, Carlos (2013a). "Las islas Chafarinas, desde 1848 hasta finales del siglo XIX" (PDF). Aldaba (37). Melilla: Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia: 191–219. doi:10.5944/aldaba.37.2013.20543.

- Esquembri Hinojo, Carlos (2013b). "Chafarinas durante el siglo XX". Aldaba (38). Melilla: Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia: 9–42. doi:10.5944/aldaba.38.2013.20546.

- Jiménez García-Carriazo, Ángeles (2018). La ampliación de la plataforma continental más allá de las doscientas millas marinas.Especial referencia a España. Madrid: Dykinson. ISBN 9788491486770.

- Madariaga, María Rosa (7 September 2012). "Los intentos de deshacerse de los enclaves". El País.

- Pineda, Antonio; Barrera, José Luis (2013). "Geología de las islas Chafarinas" (PDF). Aldaba (37). Melilla: Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia: 9. doi:10.5944/aldaba.37.2013.20542.