Italian Battleship Conte Di Cavour

During World War II, both Conte di Cavour and her sister ship, Giulio Cesare, participated in the Battle of Calabria in July 1940, where the latter was lightly damaged. Conte di Cavour was badly damaged when British torpedo bombers attacked the fleet at Taranto in November 1940. She was deliberately run aground, with most of her hull underwater, and repairs were not completed before the Italian armistice in September 1943. The ship was then captured by the Germans, but they made no effort to finish her repairs. She was damaged in an Allied air raid in early 1945 and capsized a week later. Conte di Cavour was eventually scrapped in 1946.

Description

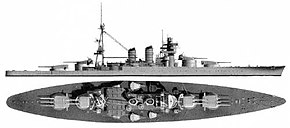

The Conte di Cavour class was designed to counter the French Courbet-class dreadnoughts which caused them to be slower and more heavily armored than the first Italian dreadnought, Dante Alighieri. The ships were 168.9 meters (554 ft 2 in) long at the waterline and 176 meters (577 ft 5 in) overall. They had a beam of 28 meters (91 ft 10 in), and a draft of 9.3 meters (30 ft 6 in). The Conte di Cavour-class ships displaced 23,088 long tons (23,458 t) at normal load, and 25,086 long tons (25,489 t) at deep load. They had a crew of 31 officers and 969 enlisted men. The ships were powered by three sets of Parsons steam turbines, two sets driving the outer propeller shafts and one set the two inner shafts. Steam for the turbines was provided by twenty Blechynden water-tube boilers, eight of which burned oil and twelve of which burned both fuel oil and coal. Designed to reach a maximum speed of 22.5 knots (41.7 km/h; 25.9 mph) from 31,000 shaft horsepower (23,000 kW), Conte di Cavour failed to reach this goal on her sea trials, despite mildly exceeding the rated power of her turbines, reaching only 22.2 knots (41.1 km/h; 25.5 mph) from 31,278 shp (23,324 kW). The ships carried enough coal and oil to give them a range of 4,800 nautical miles (8,900 km; 5,500 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph).

Armament and armor

The main battery of the Conte di Cavour class consisted of thirteen 305-millimeter Model 1909 guns, in five centerline gun turrets, with a twin-gun turret superfiring over a triple-gun turret in fore and aft pairs, and a third triple turret amidships. Their secondary armament consisted of eighteen 120-millimeter (4.7 in) guns mounted in casemates on the sides of the hull in single mounts. For defense against torpedo boats, the ships carried fourteen 76.2-millimeter (3 in) guns; thirteen of these could be mounted on the turret tops, but they could also be positioned in 30 different locations, including some on the forecastle and upper decks. They were also fitted with three submerged 450-millimeter (17.7 in) torpedo tubes, one on each broadside and the third in the stern.

The Conte di Cavour-class ships had a complete waterline armor belt that had a maximum thickness of 250 millimeters (9.8 in) amidships, which reduced to 130 millimeters (5.1 in) towards the stern and 80 millimeters (3.1 in) towards the bow. They had two armored decks: the main deck was 24 mm (0.94 in) thick on the flat that increased to 40 millimeters (1.6 in) on the slopes that connected it to the main belt. The second deck was 30 millimeters (1.2 in) thick. Frontal armor of the gun turrets was 280 millimeters (11 in) in thickness and the sides were 240 millimeters (9.4 in) thick. The armor protecting their barbettes ranged in thickness from 130 to 230 millimeters (5.1 to 9.1 in). The walls of the forward conning tower were 280 millimeters thick.

Modifications and reconstruction

Shortly after the end of World War I, the number of 76.2 mm low-angle guns was reduced to 13, all mounted on the turret tops, and six new 76.2 mm anti-aircraft (AA) guns were installed abreast the aft funnel. In addition two license-built 2-pounder (1.6 in (40 mm)) AA guns were mounted on the forecastle deck. In 1925–1926 the foremast was replaced by a four-legged (tetrapodal) mast, which was moved forward of the funnels, the rangefinders were upgraded, and the ship was equipped to handle a Macchi M.18 seaplane mounted on the amidships turret. Around the same time she was equipped with a fixed aircraft catapult on the port side of the forecastle.

Conte di Cavour began an extensive reconstruction in October 1933 at the Cantieri Riuniti dell'Adriatico shipyard in Trieste that lasted until June 1937. A new bow section was grafted over the existing bow, which increased her overall length by 10.31 meters (33 ft 10 in) to 186.4 meters (611 ft 7 in) and her beam increased to 28.6 meters (93 ft 10 in). The ship's draft at deep load increased to 10.02 meters (32 ft 10 in). All of the changes made increased her displacement to 26,140 long tons (26,560 t) at standard load and 29,100 long tons (29,600 t) at deep load. The ship's crew increased to 1,260 officers and enlisted men. Two of the propeller shafts were removed and the existing turbines were replaced by two Belluzzo geared steam turbines rated at 75,000 shp (56,000 kW). The boilers were replaced by eight Yarrow boilers. In service her maximum speed was about 27 knots (50 km/h; 31 mph) and she had a range of 6,400 nautical miles (11,900 km; 7,400 mi) at a speed of 13 knots (24 km/h; 15 mph).

The main guns were bored out to 320 millimeters (12.6 in) and the amidships turret and the torpedo tubes were removed. All of the existing secondary armament and AA guns were replaced by a dozen 120 mm guns in six twin-gun turrets and eight 100 mm (3.9 in) AA guns in twin turrets. In addition the ship was fitted with a dozen Breda 37-millimeter (1.5 in) light AA guns in six twin-gun mounts and twelve 13.2-millimeter (0.52 in) Breda M31 anti-aircraft machine guns, also in twin mounts. In 1940 the 13.2 mm machine guns were replaced by 20 mm (0.8 in) AA guns in twin mounts. The tetrapodal mast was replaced with a new forward conning tower, protected with 260-millimeter (10.2 in) thick armor. Atop the conning tower there was a fire-control director fitted with two large stereo-rangefinders, with a base length of 7.2 meters (23.6 ft).

The deck armor was increased during the reconstruction to a total of 135 millimeters (5.3 in) over the engine and boiler rooms and 166 millimeters (6.5 in) over the magazines, although its distribution over three decks meant that it was considerably less effective than a single plate of the same thickness. The armor protecting the barbettes was reinforced with 50-millimeter (2 in) plates. All this armor weighed a total of 3,227 long tons (3,279 t). The existing underwater protection was replaced by the Pugliese torpedo defense system; a large cylinder surrounded by fuel oil or water that was intended to absorb the blast of a torpedo warhead. It lacked enough depth to be fully effective against contemporary torpedoes. A major problem of the reconstruction was that the ship's increased draft meant that their waterline armor belt was almost completely submerged with any significant load.

Construction and service

Conte di Cavour, named after the statesman Count Camillo Benso di Cavour, was laid down at Arsenale di La Spezia, La Spezia, on 10 August 1910, and launched on 10 August 1911. She was completed on 1 April 1915, and served as a flagship in the southern Adriatic Sea during World War I. She saw no action, however, and spent little time at sea. Admiral Paolo Thaon di Revel, the Italian naval chief of staff, believed that Austro-Hungarian submarines and minelayers could operate too effectively in the narrow waters of the Adriatic. The threat from these underwater weapons to his capital ships was too serious for him to actively deploy the fleet. Instead, Revel decided to implement a blockade at the relatively safer southern end of the Adriatic with the battle fleet, while smaller vessels, such as MAS torpedo boats, conducted raids on Austro-Hungarian ships and installations. Meanwhile, Revel's battleships would be preserved to confront the Austro-Hungarian battle fleet in the event that it sought a decisive engagement.

In 1919 she sailed to North America and visited ports in the United States as well as Halifax, Canada. The ship was mostly inactive in 1921 because of personnel shortages, and was refitted at La Spezia from November to March 1922. Conte di Cavour and Giulio Cesare supported Italian operations on Corfu in 1923 after an Italian general and his staff were murdered at the Greek–Albanian frontier; Italian leader Benito Mussolini, who had been looking for a pretext to seize Corfu, ordered Italian troops to occupy the island. Conte di Cavour bombarded the main town on the island with her 76 mm guns, killing 20 civilians and wounding 32. She escorted King Victor Emmanuel III and his wife aboard Dante Alighieri on a state visit to Spain in 1924, and was placed in reserve upon her return until 1926, when, in April, she conveyed Mussolini on a voyage to Libya. The ship was again placed in reserve from 1927 until 1933, when she began her reconstruction.

World War II

Early in World War II, the Conte di Cavour and her sister took part in the Battle of Calabria (also known as the Battle of Punta Stilo) on 9 July 1940. They were part of the 1st Battle Squadron, commanded by Admiral Inigo Campioni, when they engaged major elements of the British Mediterranean Fleet. The British were escorting a convoy from Malta to Alexandria, while the Italians had finished escorting another from Naples to Benghazi, Italian Libya. Vice Admiral Andrew Cunningham, commander of the Mediterranean Fleet, attempted to interpose his ships between the Italians and their base at Taranto. Crews on the fleets spotted each other in the middle of the afternoon and the Italian battleships opened fire at 15:53 at a range of nearly 27,000 meters (29,000 yd). The two leading British battleships, HMS Warspite and Malaya, replied a minute later. Three minutes after she opened fire, shells from Giulio Cesare began to straddle Warspite which made a small turn and increased speed, to throw off the Italian ship's aim, at 16:00. At the same time, a shell from Warspite struck Giulio Cesare at a distance of about 24,000 meters (26,000 yd). Uncertain how severe the damage was, Campioni ordered his battleships to turn away in the face of superior British numbers and they successfully disengaged. Repairs to Giulio Cesare were completed by the end of August and both ships unsuccessfully attempted to intercept British convoys to Malta in August and September.

On the night of 11 November 1940, Conte di Cavour was at anchor in Taranto harbor when she was attacked, along with several other warships, by 21 Fairey Swordfish torpedo bombers from the British aircraft carrier HMS Illustrious. The ship's gunners shot down one Swordfish shortly after the aircraft dropped its torpedo, but it exploded underneath 'B' turret at 23:15, knocking out the main bow pump. Her captain requested tugboats to help ground the ship on a nearby 12-meter (39 ft) sandbank at 23:27, but Admiral Bruno Brivonesi, commander of the 5th Battleship Division, vetoed the request until it was too late and Conte di Cavour had to use a deeper, 17-meter (56 ft), sandbank at 04:45 the following morning. She initially grounded on an even keel, but temporarily took on a 50-degree list before settling to the bottom at 08:00 with an 11.5-degree list. Only her superstructure and gun turrets were above water by this time.

Conte di Cavour had the lowest priority for salvage among the three battleships sunk during the attack and little work was done for several months. The first priority was to patch the holes in the hull and then her guns and parts of her superstructure were removed to lighten the ship. False bulwarks were welded to the upper sides of the hull to prevent water from reentering the hull and pumping the water overboard began in May 1941. Some 15,000 long tons (15,000 t) of water were pumped out before Conte di Cavour was refloated on 9 June and entered the ex-Austro-Hungarian floating dry dock GO-12 on 12 July. The damage was more extensive than originally thought and temporary repairs to enable the ship to reach Trieste for permanent repairs took until 22 December.

Her guns were operable by September 1942, but replacing her entire electrical system took longer so the navy took advantage of the delays and incorporated some modifications to reduce the likelihood of flooding based on lessons learned from the attack. Other changes planned were the replacement of her secondary and anti-aircraft weapons with a dozen 135-millimeter (5.3 in) dual-purpose guns in twin mounts, twelve 65-millimeter (2.6 in), and twenty-three 20 mm AA guns. The repair work was suspended in June 1943, with an estimated six months work remaining on Conte di Cavour, in order to expedite the construction of urgently needed smaller ships. She was captured by the Germans on 8 September when Italy surrendered to the Allies, and was reduced to a hulk. She was damaged in an air raid on 17 February 1945, and capsized on 23 February. Refloated shortly after the end of the war, Conte di Cavour was scrapped in 1946.

Notes

- ^ Giorgerini, p. 269

- ^ Fraccaroli, p. 259

- ^ Giorgerini, pp. 270, 272

- ^ Giorgerini, pp. 268, 272

- ^ Hore, p. 175

- ^ Giorgerini, pp. 268, 277–278

- ^ Giorgerini, pp. 270–272

- ^ McLaughlin, p. 421

- ^ Giorgerini, p. 277

- ^ Whitley, p. 158

- ^ Bagnasco & Grossman, p. 64

- ^ Bargoni & Gay, p. 18

- ^ Bargoni & Gay, p. 19

- ^ Brescia, p. 58

- ^ Bagnasco & Grossman, pp. 64–65

- ^ Bagnasco & Grossman, p. 65

- ^ Bargoni & Gay, p. 21

- ^ McLaughlin, pp. 421–422

- ^ Silverstone, p. 296

- ^ Preston, p. 176

- ^ Halpern, p. 150

- ^ Halpern, pp. 141–142

- ^ Whitley, pp. 158–161

- ^ "Bombardment of Corfu". The Morning Bulletin. Rockhampton, Queensland, Australia: National Library of Australia. 1 October 1935. p. 6. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- ^ O'Hara, pp. 28–35

- ^ Whitley, p. 161

- ^ Cernuschi & O'Hara, pp. 81–85, 88

- ^ Cernuschi & O'Hara, pp. 88–92

- ^ Cernuschi & O'Hara, p. 92

- ^ Cernuschi & O'Hara, pp. 92–93

- ^ Brescia, p. 59

References

- Bagnasco, Ermino & de Toro, Augusto (2021). Italian Battleships: Conti di Cavour and Duilio Classes 1911–1956. Barnsley, UK: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-5267-9987-6.

- Bagnasco, Erminio & Grossman, Mark (1986). Regia Marina: Italian Battleships of World War Two: A Pictorial History. Missoula, Montana: Pictorial Histories Publishing. ISBN 0-933126-75-1.

- Bargoni, Franco & Gay, Franco (1972). Corazzate classe Conte di Cavour. Rome: Bizzarri. OCLC 34904733.

- Brescia, Maurizio (2012). Mussolini's Navy: A Reference Guide to the Regina Marina 1930–45. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-544-8.

- Cernuschi, Enrico & O'Hara, Vincent P. (2010). "Taranto: The Raid and the Aftermath". In Jordan, John (ed.). Warship 2010. London: Conway. pp. 77–95. ISBN 978-1-84486-110-1.

- Fraccaroli, Aldo (1985). "Italy". In Gray, Randal (ed.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. pp. 252–290. ISBN 978-0-87021-907-8.

- Giorgerini, Giorgio (1980). "The Cavour & Duilio Class Battleships". In Roberts, John (ed.). Warship IV. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 267–279. ISBN 0-85177-205-6.

- Halpern, Paul G. (1995). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-352-4.

- McLaughlin, Stephen (2003). Russian & Soviet Battleships. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-481-4.

- O'Hara, Vincent P. (2008). "The Action off Calabria and the Myth of Moral Ascendancy". In Jordan, John (ed.). Warship 2008. London: Conway. pp. 26–39. ISBN 978-1-84486-062-3.

- Ordovini, Aldo F.; Petronio, Fulvio; et al. (December 2017). "Capital Ships of the Royal Italian Navy, 1860–1918: Part 4: Dreadnought Battleships". Warship International. LIV (4): 307–343. ISSN 0043-0374.

- Preston, Antony (1972). Battleships of World War I: An Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Battleships of All Nations 1914–1918. New York: Galahad Books. ISBN 0-88365-300-1.

- Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World's Capital Ships. New York: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 0-88254-979-0.

- Whitley, M. J. (1998). Battleships of World War II. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-184-X.

Further reading

- Fraccaroli, Aldo (1970). Italian Warships of World War I. London: Ian Allan. ISBN 978-0-7110-0105-3.

External links