Itmad-Ud-Daulah

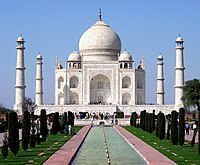

Along with the main building, the structure consists of numerous outbuildings and gardens. The tomb, built between 1622 and 1628, represents a transition between the first phase of monumental Mughal architecture – primarily built from red sandstone with marble decorations, as in Humayun's Tomb in Delhi and Akbar's tomb in Sikandra – to its second phase, based on white marble and pietra dura inlay, most elegantly realized in the Taj Mahal.

The mausoleum was commissioned by Nur Jahan, the wife of Jahangir, for her father Mirzā Ghiyās Beg, originally a Persian Amir in exile, who had been given the title of I'timād-ud-Daulah (pillar of the state). Mirzā Ghiyās Beg was also the grandfather of Mumtāz Mahāl (originally named Arjumand Banu Begum, daughter of Asaf Khan), the wife of the emperor Shah Jahan, responsible for the construction of the Taj Mahal.

Tomb

The mausoleum, located in the centre of a quadrangle (charbagh) on the left banks of river Yamuna next to Chini Ka Rauza, covers about 23 square metres (250 sq ft), and is built on a red sandstone plinth of about 50 square metres (540 sq ft) and about 1 metre (3.3 ft) high. On each corner are octagonal minarets, about 13 metres (43 ft) tall.

The walls are made up from white marble from Rajasthan encrusted with semi-precious stone decorations: cornelian, jasper, lapis lazuli, onyx and topaz formed into images of cypress trees and wine bottles, or more elaborate decorations like cut fruit or vases containing bouquets. Light penetrates to the interior through delicate jali screens of intricately carved white marble. The interior decoration is considered by many to have inspired that of the Taj Mahal, which was built by her stepson, Mughal ruler Shah Jahan.

Many of Nūr Jahān's relatives are interred in the mausoleum. The only asymmetrical element of the entire complex is that the cenotaphs of her father and mother have been set side-by-side, a formation replicated in the Taj Mahal.

History

This is the tomb of Mirza Ghiyas Beg and his wife Asmat Begum. He hailed from Iran and served Akbar and was the father of the famous Nur Jahan and grandfather of Mumtaz Mahal of the Taj Mahal fame. He was made Vazir (Prime Minister) after Nur Jahan's marriage with Jahangir in 1611 and held the mansab of 7000/7000 and the title : "I'timad-Ud-Daulah" (The Lord treasurer). He died at Agra in 1622, a few months after his wife's death. Nur Jahan built this tomb for her parents between 1622 and 1628. Her own tomb and that of Jahangir are at Lahore.

The Tomb of I'timad-Ud-Daulah is a masterpiece of the domeless class of Mughal tombs. It is the first building finished in white marble and marks the transitional phase from red sandstone to white marble, from Akbar's tomb Sikandra to the Taj Mahal.

Architecture

The tomb, situated on the eastern bank of the river Yamuna, is planned in the centre of a Char-Bagh (four-quartered garden), with the usual enclosing walls and side buildings. As conditioned by its situation, the main gate is on the eastern side. Ornamental gateways with prominent lawns are built in the middle of north and south sides. A multi-storeyed open pleasure pavilion is there on the western side, overlooking the river impressively. These buildings are of red sandstone with bold inlaid designs in white marble.

Shallow water channels, sunk in the middle of the raised stone paved pathways, with intermittent tanks and cascades, divided the garden into four equal quarters. They are only slightly raised from the parterres which could be converted into flower beds. Space for large plants and trees was reserved just adjoining the enclosing walls, leaving the mausoleum fully open to view.

The main tomb of white marble is marvellously set in the centre of the garden. It stands on a plinth with a stairway of red stone, having in the middle of each side facing the central arch, a lotus tank with fountain. The tomb is square in plan with octagonal towers at the corners, surmounted by chhatris, attached to its corners. Each facade has three depressed arches: the central one providing the entrance, and the other two on the sides being closed by jalis. Each side is protected by a chhajja and a jali balustrade above it. There is no dome; instead, the building is roofed by a square baradari and an ogee-curved roof with a chajja, having three arched openings on each side which are closed by jalis except in the middle of the north and south sides. Each minaret has cusped arches and is crowned by a domed roof with padmakosha (lotus petals) and Kalasha finials. The plinth and the roof is lined with a parapet of sandstone and marble respectively with lattice-work. The plinth also has a star-pattern inlay The interior is composed of a central square hall housing the cenotaphs of Asmat Begum and her husband, Mirza Ghiyas. four oblong rooms on the sides and four square rooms on the corners, all interconnected by common doorways. The cenotaph of Asmat Begum and her husband occupies the exact centre of the hall. Corner rooms have tombstones of Nur Jahan's other relations.

The most important aspect of this tomb is its polychrome ornamentation. Beautiful, floral, and stylized arabesque (spandrel and interior), geometrical designs (parapet and jali), opus sectile mosaic with (stones, tiles, glass and enamel) and slices of pietra dura inlay (of semi-precious stones) have been decorated on the whole exterior in inlay and mosaic techniques, in various pleasing tints and tones. Wine vase, dish and cup, cypress, honeysuckle, guldasta (flower bouquet) and such other Iranian motifs, typical of the art of Jahangir, have been emphatically used. Some compositions have been inspired by the plant studies of Ustad Mansur Naqqash, the famous "fauna and flora" painter of Jehangir. Some stylized designs have also been done in exquisite carving, both incised and relief. They look like embroidery work done in ivory. Delicacy is their quality. Stucco and painting have been done in the interior where minute animal and human figures have also been shown. The inspiration has come from the contemporary art of painting. There is no glazed tiling and the decoration is largely by coloured stones which is an indigenous development.

Chapters 48 and 73 of the Quran have been carved on the 64 panels on the external sides of the ground floor. The date of writing A.H. 1037/1627 A.D. is mentioned in the last panel. Chapter 67 of the Quran is inscribed on the 12 internal panels of the upper pavilion.

This is protected and conserved by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI).

Gallery

-

Corner view

-

General view from the river

-

Entrance gate, outside view

-

Entrance gate, inside view

-

Mausoleum seen from the gate

-

Mausoleum from the west

-

Corner view

-

Domed top of minaret

-

Cornice and supports, detail

-

Exterior wall, detail with niche

-

Exterior wall, detail with niche

-

Geometrically patterned panel with 10-point stars

-

Jali pierced stone screen

-

Pietra dura vases in marble wall with geometric floral border

-

Interior decorated with vases, vegetal and geometric patterns

-

Pietra dura on mausoleum interior wall

-

Pietra dura on mausoleum interior wall

-

Corner View (under direct sunlight )

See also

- Tomb of Nur Jahan

- Indo-Islamic architecture

- Tomb of Jahangir

- Taj Mahal

- Humayun's Tomb

- Mirza Ghiyas Beg

- Agra

- Fatehpur Sikri

- Bibi Ka Maqbara

- Bahmani Tombs

- Tughluq tombs

References

- ^ Datta, Rangan (5 July 2024). "Agra beyond the Taj: Exploring tombs and gardens on the left bank of Yamuna". The Telegraph. My Kolkata. Retrieved 18 July 2024.

- ^ "Itimad ud Daulah". Agra Tourism. Retrieved 18 July 2024.

- ^ "Itimad ud Daulah". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 18 July 2024.

- ^ کتاب سفرنامه هند ص55–58 در سال ۱۳۵۰ خورشیدی. نوشته محمدرضا خانی. به فارسی.

- ^ "Itmad-ud-daulah-tomb - Archaeological Survey of India, Agra Circle, Agra". ASI Agra Circle. Retrieved 24 December 2024.

- ^ "Architecture". The Ultimate Visual Family Dictionary. New Delhi: DK Pub. 2012. p. 488-489. ISBN 978-0-1434-1954-9.

- ^ Sharma, Snigdha (20 January 2024). "Here's Why The Tomb of Itimad-ud-Daulah In Agra Is A Must-See". Outlook. Outlook Traveller. Retrieved 18 July 2024.

- ^ "Itimad Ud Daulah". Agra Development Authority. Retrieved 24 December 2024.

- ^ "Tombs of Jahangir, Asif Khan and Akbari Sarai, Lahore - UNESCO World Heritage Centre". UNESCO. Retrieved 24 December 2024.

- ^ A.S., Bhalla (2009). Royal Tombs of India:13th to 18th Century. Mapin. p. 117-121. ISBN 978-81-89995-10-2.

External links

- Itmad ud Daulah on YouTube

- Pictures of Etimad-ud-Daulah's Tomb Pictures of Itmad-Ud-Daulah's Tomb from a backpackers trip around India