Jupiter's Magnetosphere

Jupiter's internal magnetic field is generated by electrical currents in the planet's outer core, which is theorized to be composed of liquid metallic hydrogen. Volcanic eruptions on Jupiter's moon Io eject large amounts of sulfur dioxide gas into space, forming a large torus around the planet. Jupiter's magnetic field forces the torus to rotate with the same angular velocity and direction as the planet. The torus in turn loads the magnetic field with plasma, in the process stretching it into a pancake-like structure called a magnetodisk. In effect, Jupiter's magnetosphere is internally driven, shaped primarily by Io's plasma and its own rotation, rather than by the solar wind as at Earth's magnetosphere. Strong currents in the magnetosphere generate permanent aurorae around the planet's poles and intense variable radio emissions, which means that Jupiter can be thought of as a very weak radio pulsar. Jupiter's aurorae have been observed in almost all parts of the electromagnetic spectrum, including infrared, visible, ultraviolet and soft X-rays.

The action of the magnetosphere traps and accelerates particles, producing intense belts of radiation similar to Earth's Van Allen belts, but thousands of times stronger. The interaction of energetic particles with the surfaces of Jupiter's largest moons markedly affects their chemical and physical properties. Those same particles also affect and are affected by the motions of the particles within Jupiter's tenuous planetary ring system. Radiation belts present a significant hazard for spacecraft and potentially to human space travellers.

Structure

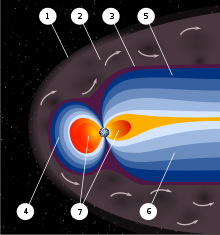

Jupiter's magnetosphere is a complex structure comprising a bow shock, magnetosheath, magnetopause, magnetotail, magnetodisk, and other components. The magnetic field around Jupiter emanates from a number of different sources, including fluid circulation at the planet's core (the internal field), electrical currents in the plasma surrounding Jupiter and the currents flowing at the boundary of the planet's magnetosphere. The magnetosphere is embedded within the plasma of the solar wind, which carries the interplanetary magnetic field.

Internal magnetic field

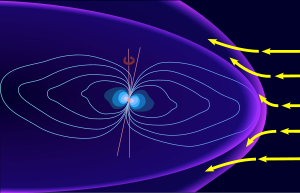

The bulk of Jupiter's magnetic field, like Earth's, is generated by an internal dynamo supported by the circulation of a conducting fluid in its outer core. But whereas Earth's core is made of molten iron and nickel, Jupiter's is composed of metallic hydrogen. As with Earth's, Jupiter's magnetic field is mostly a dipole, with north and south magnetic poles at the ends of a single magnetic axis. On Jupiter the north pole of the dipole (where magnetic field lines point radially outward) is located in the planet's northern hemisphere and the south pole of the dipole lies in its southern hemisphere. This is opposite from the Earth. Jupiter's field also has quadrupole, octupole and higher components, though they are less than one-tenth as strong as the dipole component.

The dipole is tilted roughly 10° from Jupiter's axis of rotation; the tilt is similar to that of the Earth (11.3°). Its equatorial field strength is about 417.0 μT (4.170 G), which corresponds to a dipole magnetic moment of about 2.83 × 10 T·m. This makes Jupiter's magnetic field about 20 times stronger than Earth's, and its magnetic moment ~20,000 times larger. Jupiter's magnetic field rotates at the same speed as the region below its atmosphere, with a period of 9 h 55 m. No changes in its strength or structure had been observed since the first measurements were taken by the Pioneer spacecraft in the mid-1970s, until 2019. Analysis of observations from the Juno spacecraft show a small but measurable change from the planet's magnetic field observed during the Pioneer era. In particular, Jupiter has a region of strongly non-dipolar field, known as the "Great Blue Spot", near the equator. This may be roughly analogous to the Earth's South Atlantic Anomaly. This region shows signs of large secular variations.

Size and shape

Jupiter's internal magnetic field prevents the solar wind, a stream of ionized particles emitted by the Sun, from interacting directly with its atmosphere, and instead diverts it away from the planet, effectively creating a cavity in the solar wind flow, called a magnetosphere, composed of a plasma different from that of the solar wind. The Jovian magnetosphere is so large that the Sun and its visible corona would fit inside it with room to spare. If one could see it from Earth, it would appear five times larger than the full moon in the sky despite being nearly 1700 times farther away.

As with Earth's magnetosphere, the boundary separating the denser and colder solar wind's plasma from the hotter and less dense one within Jupiter's magnetosphere is called the magnetopause. The distance from the magnetopause to the center of the planet is from 45 to 100 RJ (where RJ=71,492 km is the radius of Jupiter) at the subsolar point—the unfixed point on the surface at which the Sun would appear directly overhead to an observer. The position of the magnetopause depends on the pressure exerted by the solar wind, which in turn depends on solar activity. In front of the magnetopause (at a distance from 80 to 130 RJ from the planet's center) lies the bow shock, a wake-like disturbance in the solar wind caused by its collision with the magnetosphere. The region between the bow shock and magnetopause is called the magnetosheath.

At the opposite side of the planet, the solar wind stretches Jupiter's magnetic field lines into a long, trailing magnetotail, which sometimes extends well beyond the orbit of Saturn. The structure of Jupiter's magnetotail is similar to Earth's. It consists of two lobes (blue areas in the figure), with the magnetic field in the southern lobe pointing toward Jupiter, and that in the northern lobe pointing away from it. The lobes are separated by a thin layer of plasma called the tail current sheet (orange layer in the middle).

The shape of Jupiter's magnetosphere described above is sustained by the neutral sheet current (also known as the magnetotail current), which flows with Jupiter's rotation through the tail plasma sheet, the tail currents, which flow against Jupiter's rotation at the outer boundary of the magnetotail, and the magnetopause currents (or Chapman–Ferraro currents), which flow against rotation along the dayside magnetopause. These currents create the magnetic field that cancels the internal field outside the magnetosphere. They also interact substantially with the solar wind.

Jupiter's magnetosphere is traditionally divided into three parts: the inner, middle and outer magnetosphere. The inner magnetosphere is located at distances closer than 10 RJ from the planet. The magnetic field within it remains approximately dipole, because contributions from the currents flowing in the magnetospheric equatorial plasma sheet are small. In the middle (between 10 and 40 RJ) and outer (further than 40 RJ) magnetospheres, the magnetic field is not a dipole, and is seriously disturbed by its interaction with the plasma sheet (see magnetodisk below).

Role of Io

Although overall the shape of Jupiter's magnetosphere resembles that of the Earth's, closer to the planet its structure is very different. Jupiter's volcanically active moon Io is a strong source of plasma in its own right, and loads Jupiter's magnetosphere with as much as 1,000 kg of new material every second. Strong volcanic eruptions on Io emit huge amounts of sulfur dioxide, a major part of which is dissociated into atoms and ionized by electron impacts and, to a lesser extent, solar ultraviolet radiation, producing ions of sulfur and oxygen. Further electron impacts produce higher charge state, resulting in a plasma of S, O, S, O and S. They form the Io plasma torus: a thick and relatively cool ring of plasma encircling Jupiter, located near Io's orbit. The plasma temperature within the torus is 10–100 eV (100,000–1,000,000 K), which is much lower than that of the particles in the radiation belts—10 keV (100 million K). The plasma in the torus is forced into co-rotation with Jupiter, meaning both share the same period of rotation. The Io torus fundamentally alters the dynamics of the Jovian magnetosphere.

As a result of several processes—diffusion and interchange instability being the main escape mechanisms—the plasma slowly leaks away from Jupiter. As the plasma moves further from the planet, the radial currents flowing within it gradually increase its velocity, maintaining co-rotation. These radial currents are also the source of the magnetic field's azimuthal component, which as a result bends back against the rotation. The particle number density of the plasma decreases from around 2,000 cm in the Io torus to about 0.2 cm at a distance of 35 RJ. In the middle magnetosphere, at distances greater than 10 RJ from Jupiter, co-rotation gradually breaks down and the plasma begins to rotate more slowly than the planet. Eventually at the distances greater than roughly 40 RJ (in the outer magnetosphere) this plasma is no longer confined by the magnetic field and leaves the magnetosphere through the magnetotail. As cold, dense plasma moves outward, it is replaced by hot, low-density plasma, with temperatures of up to 20 keV (200 million K) or higher) moving in from the outer magnetosphere. Some of this plasma, adiabatically heated as it approaches Jupiter, may form the radiation belts in Jupiter's inner magnetosphere.

Magnetodisk

While Earth's magnetic field is roughly teardrop-shaped, Jupiter's is flatter, more closely resembling a disk, and "wobbles" periodically about its axis. The main reasons for this disk-like configuration are the centrifugal force from the co-rotating plasma and thermal pressure of hot plasma, both of which act to stretch Jupiter's magnetic field lines, forming a flattened pancake-like structure, known as the magnetodisk, at the distances greater than 20 RJ from the planet. The magnetodisk has a thin current sheet at the middle plane, approximately near the magnetic equator. The magnetic field lines point away from Jupiter above the sheet and towards Jupiter below it. The load of plasma from Io greatly expands the size of the Jovian magnetosphere, because the magnetodisk creates an additional internal pressure which balances the pressure of the solar wind. In the absence of Io the distance from the planet to the magnetopause at the subsolar point would be no more than 42 RJ, whereas it is actually 75 RJ on average.

The configuration of the magnetodisk's field is maintained by the azimuthal ring current (not an analog of Earth's ring current), which flows with rotation through the equatorial plasma sheet. The Lorentz force resulting from the interaction of this current with the planetary magnetic field creates a centripetal force, which keeps the co-rotating plasma from escaping the planet. The total ring current in the equatorial current sheet is estimated at 90–160 million amperes.

Dynamics

Co-rotation and radial currents

The main driver of Jupiter's magnetosphere is the planet's rotation. In this respect Jupiter is similar to a device called a Unipolar generator. When Jupiter rotates, its ionosphere moves relatively to the dipole magnetic field of the planet. Because the dipole magnetic moment points in the direction of the rotation, the Lorentz force, which appears as a result of this motion, drives negatively charged electrons to the poles, while positively charged ions are pushed towards the equator. As a result, the poles become negatively charged and the regions closer to the equator become positively charged. Since the magnetosphere of Jupiter is filled with highly conductive plasma, the electrical circuit is closed through it. A current called the direct current flows along the magnetic field lines from the ionosphere to the equatorial plasma sheet. This current then flows radially away from the planet within the equatorial plasma sheet and finally returns to the planetary ionosphere from the outer reaches of the magnetosphere along the field lines connected to the poles. The currents that flow along the magnetic field lines are generally called field-aligned or Birkeland currents. The radial current interacts with the planetary magnetic field, and the resulting Lorentz force accelerates the magnetospheric plasma in the direction of planetary rotation. This is the main mechanism that maintains co-rotation of the plasma in Jupiter's magnetosphere.

The current flowing from the ionosphere to the plasma sheet is especially strong when the corresponding part of the plasma sheet rotates slower than the planet. As mentioned above, co-rotation breaks down in the region located between 20 and 40 RJ from Jupiter. This region corresponds to the magnetodisk, where the magnetic field is highly stretched. The strong direct current flowing into the magnetodisk originates in a very limited latitudinal range of about 16 ± 1° from the Jovian magnetic poles. These narrow circular regions correspond to Jupiter's main auroral ovals. (See below.) The return current flowing from the outer magnetosphere beyond 50 RJ enters the Jovian ionosphere near the poles, closing the electrical circuit. The total radial current in the Jovian magnetosphere is estimated at 60 million–140 million amperes.

The acceleration of the plasma into the co-rotation leads to the transfer of energy from the Jovian rotation to the kinetic energy of the plasma. In that sense, the Jovian magnetosphere is powered by the planet's rotation, whereas the Earth's magnetosphere is powered mainly by the solar wind.

Interchange instability and reconnection

The main problem encountered in deciphering the dynamics of the Jovian magnetosphere is the transport of heavy cold plasma from the Io torus at 6 RJ to the outer magnetosphere at distances of more than 50 RJ. The precise mechanism of this process is not known, but it is hypothesized to occur as a result of plasma diffusion due to interchange instability. The process is similar to the Rayleigh-Taylor instability in hydrodynamics. In the case of the Jovian magnetosphere, centrifugal force plays the role of gravity; the heavy liquid is the cold and dense Ionian (i.e. pertaining to Io) plasma, and the light liquid is the hot, much less dense plasma from the outer magnetosphere. The instability leads to an exchange between the outer and inner parts of the magnetosphere of flux tubes filled with plasma. The buoyant empty flux tubes move towards the planet, while pushing the heavy tubes, filled with the Ionian plasma, away from Jupiter. This interchange of flux tubes is a form of magnetospheric turbulence.

This highly hypothetical picture of the flux tube exchange was partly confirmed by the Galileo spacecraft, which detected regions of sharply reduced plasma density and increased field strength in the inner magnetosphere. These voids may correspond to the almost empty flux tubes arriving from the outer magnetosphere. In the middle magnetosphere, Galileo detected so-called injection events, which occur when hot plasma from the outer magnetosphere impacts the magnetodisk, leading to increased flux of energetic particles and a strengthened magnetic field. No mechanism is yet known to explain the transport of cold plasma outward.

When flux tubes loaded with the cold Ionian plasma reach the outer magnetosphere, they go through a reconnection process, which separates the magnetic field from the plasma. The former returns to the inner magnetosphere in the form of flux tubes filled with hot and less dense plasma, while the latter are probably ejected down the magnetotail in the form of plasmoids—large blobs of plasma. The reconnection processes may correspond to the global reconfiguration events also observed by the Galileo spacecraft, which occurred regularly every 2–3 days. The reconfiguration events usually included rapid and chaotic variation of the magnetic field strength and direction, as well as abrupt changes in the motion of the plasma, which often stopped co-rotating and began flowing outward. They were mainly observed in the dawn sector of the night magnetosphere. The plasma flowing down the tail along the open field lines is called the planetary wind.

The reconnection events are analogues to the magnetic substorms in the Earth's magnetosphere. The difference seems to be their respective energy sources: terrestrial substorms involve storage of the solar wind's energy in the magnetotail followed by its release through a reconnection event in the tail's neutral current sheet. The latter also creates a plasmoid which moves down the tail. Conversely, in Jupiter's magnetosphere the rotational energy is stored in the magnetodisk and released when a plasmoid separates from it.

Influence of the solar wind

Whereas the dynamics of the Jovian magnetosphere mainly depend on internal sources of energy, the solar wind probably has a role as well, particularly as a source of high-energy protons. The structure of the outer magnetosphere shows some features of a solar wind-driven magnetosphere, including a significant dawn–dusk asymmetry. In particular, magnetic field lines in the dusk sector are bent in the opposite direction to those in the dawn sector. In addition, the dawn magnetosphere contains open field lines connecting to the magnetotail, whereas in the dusk magnetosphere, the field lines are closed. All these observations indicate that a solar wind driven reconnection process, known on Earth as the Dungey cycle, may also be taking place in the Jovian magnetosphere.

The extent of the solar wind's influence on the dynamics of Jupiter's magnetosphere is currently unknown; however, it could be especially strong at times of elevated solar activity. The auroral radio, optical and X-ray emissions, as well as synchrotron emissions from the radiation belts all show correlations with solar wind pressure, indicating that the solar wind may drive plasma circulation or modulate internal processes in the magnetosphere.

Emissions

Aurorae

| Emission | Jupiter | Io spot |

|---|---|---|

| Radio (KOM, <0.3 MHz) | ~1 GW | ? |

| Radio (HOM, 0.3–3 MHz) | ~10 GW | ? |

| Radio (DAM, 3–40 MHz) | ~100 GW | 0.1–1 GW (Io-DAM) |

| IR (hydrocarbons, 7–14 μm) | ~40 TW | 30–100 GW |

| IR (H3, 3–4 μm) | 4–8 TW | |

| Visible (0.385–1 μm) | 10–100 GW | 0.3 GW |

| UV (80–180 nm) | 2–10 TW | ~50 GW |

| X-ray (0.1–3 keV) | 1–4 GW | ? |

(animation).

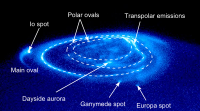

Jupiter demonstrates bright, persistent aurorae around both poles. Unlike Earth's aurorae, which are transient and only occur at times of heightened solar activity, Jupiter's aurorae are permanent, though their intensity varies from day to day. They consist of three main components: the main ovals, which are bright, narrow (less than 1000 km in width) circular features located at approximately 16° from the magnetic poles; the satellites' auroral spots, which correspond to the footprints of the magnetic field lines connecting Jupiter's ionosphere with those of its largest moons, and transient polar emissions situated within the main ovals (elliptical field may prove to be a better description). Auroral emissions have been detected in almost all parts of the electromagnetic spectrum from radio waves to X-rays (up to 3 keV); they are most frequently observed in the mid-infrared (wavelength 3–4 μm and 7–14 μm) and far ultraviolet spectral regions (wavelength 120–180 nm).

The main ovals are the dominant part of the Jovian aurorae. They have roughly stable shapes and locations, but their intensities are strongly modulated by the solar wind pressure—the stronger solar wind, the weaker the aurorae. As mentioned above, the main ovals are maintained by the strong influx of electrons accelerated by the electric potential drops between the magnetodisk plasma and the Jovian ionosphere. These electrons carry field aligned currents, which maintain the plasma's co-rotation in the magnetodisk. The potential drops develop because the sparse plasma outside the equatorial sheet can only carry a current of a limited strength without driving instabilities and producing potential drops. The precipitating electrons have energy in the range 10–100 keV and penetrate deep into the atmosphere of Jupiter, where they ionize and excite molecular hydrogen causing ultraviolet emission. The total energy input into the ionosphere is 10–100 TW. In addition, the currents flowing in the ionosphere heat it by the process known as Joule heating. This heating, which produces up to 300 TW of power, is responsible for the strong infrared radiation from the Jovian aurorae and partially for the heating of the thermosphere of Jupiter.

Spots were found to correspond to the Galilean moons Io, Europa and Ganymede. They develop because the co-rotation of the plasma interacts with the moons and is slowed in their vicinity. The brightest spot belongs to Io, which is the main source of the plasma in the magnetosphere (see above). The Ionian auroral spot is thought to be related to Alfvén currents flowing from the Jovian to Ionian ionosphere. Europa's is similar but much dimmer, because it has a more tenuous atmosphere and is a weaker plasma source. Europa's atmosphere is produced by sublimation of water ice from its surfaces, rather than the volcanic activity which produces Io's atmosphere. Ganymede has an internal magnetic field and a magnetosphere of its own. The interaction between this magnetosphere and that of Jupiter produces currents due to magnetic reconnection. The auroral spot associated with Callisto is probably similar to that of Europa, but has only been seen once as of June, 2019. Normally, magnetic field lines connected to Callisto touch Jupiter's atmosphere very close to or along the main auroral oval, making it difficult to detect Callisto's auroral spot.

Bright arcs and spots sporadically appear within the main ovals. These transient phenomena are thought to be related to interaction with either the solar wind or the dynamics of the outer magnetosphere. The magnetic field lines in this region are believed to be open or to map onto the magnetotail. The secondary ovals are sometimes observed inside the main oval and may be related to the boundary between open and closed magnetic field lines or to the polar cusps. The polar auroral emissions could be similar to those observed around Earth's poles: appearing when electrons are accelerated towards the planet by potential drops, during reconnection of solar magnetic field with that of the planet. The regions within the main ovals emits most of auroral X-rays. The spectrum of the auroral X-ray radiation consists of spectral lines of highly ionized oxygen and sulfur, which probably appear when energetic (hundreds of kiloelectronvolts) S and O ions precipitate into the polar atmosphere of Jupiter. The source of this precipitation remains unknown but this is inconsistent with the theory that these magnetic field lines are open and connect to the solar wind.

Jupiter at radio wavelengths

Jupiter is a powerful source of radio waves in the spectral regions stretching from several kilohertz to tens of megahertz. Radio waves with frequencies of less than about 0.3 MHz (and thus wavelengths longer than 1 km) are called the Jovian kilometric radiation or KOM. Those with frequencies in the interval of 0.3–3 MHz (with wavelengths of 100–1000 m) are called the hectometric radiation or HOM, while emissions in the range 3–40 MHz (with wavelengths of 10–100 m) are referred to as the decametric radiation or DAM. The latter radiation was the first to be observed from Earth, and its approximately 10-hour periodicity helped to identify it as originating from Jupiter. The strongest part of decametric emission, which is related to Io and to the Io–Jupiter current system, is called Io-DAM.

The majority of these emissions are thought to be produced by a mechanism called "cyclotron maser instability", which develops close to the auroral regions. Electrons moving parallel to the magnetic field precipitate into the atmosphere while those with a sufficient perpendicular velocity are reflected by the converging magnetic field. This results in an unstable velocity distribution. This velocity distribution spontaneously generates radio waves at the local electron cyclotron frequency. The electrons involved in the generation of radio waves are probably those carrying currents from the poles of the planet to the magnetodisk. The intensity of Jovian radio emissions usually varies smoothly with time. However, there are short and powerful bursts (S bursts) of emission superimposed on the more gradual variations and which can outshine all other components. The total emitted power of the DAM component is about 100 GW, while the power of all other HOM/KOM components is about 10 GW. In comparison, the total power of Earth's radio emissions is about 0.1 GW.

Jupiter's radio and particle emissions are strongly modulated by its rotation, which makes the planet somewhat similar to a pulsar. This periodical modulation is probably related to asymmetries in the Jovian magnetosphere, which are caused by the tilt of the magnetic moment with respect to the rotational axis as well as by high-latitude magnetic anomalies. The physics governing Jupiter's radio emissions is similar to that of radio pulsars. They differ only in the scale, and Jupiter can be considered a very small radio pulsar too. In addition, Jupiter's radio emissions strongly depend on solar wind pressure and, hence, on solar activity.

In addition to relatively long-wavelength radiation, Jupiter also emits synchrotron radiation (also known as the Jovian decimetric radiation or DIM radiation) with frequencies in the range of 0.1–15 GHz (wavelength from 3 m to 2 cm),. These emissions are from relativistic electrons trapped in the inner radiation belts of the planet. The energy of the electrons that contribute to the DIM emissions is from 0.1 to 100 MeV, while the leading contribution comes from the electrons with energy in the range 1–20 MeV. This radiation is well understood and was used since the beginning of the 1960s to study the structure of the planet's magnetic field and radiation belts. The particles in the radiation belts originate in the outer magnetosphere and are adiabatically accelerated, when they are transported to the inner magnetosphere. However, this requires a source population of moderately high energy electrons (>> 1 keV), and the origin of this population is not well understood.

Jupiter's magnetosphere ejects streams of high-energy electrons and ions (energy up to tens megaelectronvolts), which travel as far as Earth's orbit. These streams are highly collimated and vary with the rotational period of the planet like the radio emissions. In this respect as well, Jupiter shows similarity to a pulsar.

Interaction with rings and moons

Jupiter's extensive magnetosphere envelops its ring system and the orbits of all four Galilean satellites. Orbiting near the magnetic equator, these bodies serve as sources and sinks of magnetospheric plasma, while energetic particles from the magnetosphere alter their surfaces. The particles sputter off material from the surfaces and create chemical changes via radiolysis. The plasma's co-rotation with the planet means that the plasma preferably interacts with the moons' trailing hemispheres, causing noticeable hemispheric asymmetries.

Close to Jupiter, the planet's rings and small moons absorb high-energy particles (energy above 10 keV) from the radiation belts. This creates noticeable gaps in the belts' spatial distribution and affects the decimetric synchrotron radiation. In fact, the existence of Jupiter's rings was first hypothesized on the basis of data from the Pioneer 11 spacecraft, which detected a sharp drop in the number of high-energy ions close to the planet. The planetary magnetic field strongly influences the motion of sub-micrometer ring particles as well, which acquire an electrical charge under the influence of solar ultraviolet radiation. Their behavior is similar to that of co-rotating ions. Resonant interactions between the co-rotation and the particles' orbital motion has been used to explain the creation of Jupiter's innermost halo ring (located between 1.4 and 1.71 RJ). This ring consists of sub-micrometer particles on highly inclined and eccentric orbits. The particles originate in the main ring; however, when they drift toward Jupiter, their orbits are modified by the strong 3:2 Lorentz resonance located at 1.71 RJ, which increases their inclinations and eccentricities. Another 2:1 Lorentz resonance at 1.4 Rj defines the inner boundary of the halo ring.

| Moon | rem/day |

|---|---|

| Io | 3600 |

| Europa | 540 |

| Ganymede | 8 |

| Callisto | 0.01 |

| Earth (Max) | 0.07 |

| Earth (Avg) | 0.0007 |

All Galilean moons have thin atmospheres with surface pressures in the range 0.01–1 nbar, which in turn support substantial ionospheres with electron densities in the range of 1,000–10,000 cm. The co-rotational flow of cold magnetospheric plasma is partially diverted around them by the currents induced in their ionospheres, creating wedge-shaped structures known as Alfvén wings. The interaction of the large moons with the co-rotational flow is similar to the interaction of the solar wind with the non-magnetized planets like Venus, although the co-rotational speed is usually subsonic (the speeds vary from 74 to 328 km/s), which prevents the formation of a bow shock. The pressure from the co-rotating plasma continuously strips gases from the moons' atmospheres (especially from that of Io), and some of these atoms are ionized and brought into co-rotation. This process creates gas and plasma tori in the vicinity of moons' orbits with the Ionian torus being the most prominent. In effect, the Galilean moons (mainly Io) serve as the principal plasma sources in Jupiter's inner and middle magnetosphere. Meanwhile, the energetic particles are largely unaffected by the Alfvén wings and have free access to the moons' surfaces (except Ganymede's).

The icy Galilean moons, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto, all generate induced magnetic moments in response to changes in Jupiter's magnetic field. These varying magnetic moments create dipole magnetic fields around them, which act to compensate for changes in the ambient field. The induction is thought to take place in subsurface layers of salty water, which are likely to exist in all of Jupiter's large icy moons. These underground oceans can potentially harbor life, and evidence for their presence was one of the most important discoveries made in the 1990s by spacecraft.

The interaction of the Jovian magnetosphere with Ganymede, which has an intrinsic magnetic moment, differs from its interaction with the non-magnetized moons. Ganymede's internal magnetic field carves a cavity inside Jupiter's magnetosphere with a diameter of approximately two Ganymede diameters, creating a mini-magnetosphere within Jupiter's magnetosphere. Ganymede's magnetic field diverts the co-rotating plasma flow around its magnetosphere. It also protects the moon's equatorial regions, where the field lines are closed, from energetic particles. The latter can still freely strike Ganymede's poles, where the field lines are open. Some of the energetic particles are trapped near the equator of Ganymede, creating mini-radiation belts. Energetic electrons entering its thin atmosphere are responsible for the observed Ganymedian polar aurorae.

Charged particles have a considerable influence on the surface properties of Galilean moons. Plasma originating from Io carries sulfur and sodium ions farther from the planet, where they are implanted preferentially on the trailing hemispheres of Europa and Ganymede. On Callisto however, for unknown reasons, sulfur is concentrated on the leading hemisphere. Plasma may also be responsible for darkening the moons' trailing hemispheres (again, except Callisto's). Energetic electrons and ions, with the flux of the latter being more isotropic, bombard surface ice, sputtering atoms and molecules off and causing radiolysis of water and other chemical compounds. The energetic particles break water into oxygen and hydrogen, maintaining the thin oxygen atmospheres of the icy moons (since the hydrogen escapes more rapidly). The compounds produced radiolytically on the surfaces of Galilean moons also include ozone and hydrogen peroxide. If organics or carbonates are present, carbon dioxide, methanol and carbonic acid can be produced as well. In the presence of sulfur, likely products include sulfur dioxide, hydrogen disulfide and sulfuric acid. Oxidants produced by radiolysis, like oxygen and ozone, may be trapped inside the ice and carried downward to the oceans over geologic time intervals, thus serving as a possible energy source for life.

Discovery

The first evidence for the existence of Jupiter's magnetic field came in 1955, with the discovery of the decametric radio emission or DAM. As the DAM's spectrum extended up to 40 MHz, astronomers concluded that Jupiter must possess a magnetic field with a maximum strength of above 1 milliteslas (10 gauss).

In 1959, observations in the microwave part of the electromagnetic (EM) spectrum (0.1–10 GHz) led to the discovery of the Jovian decimetric radiation (DIM) and the realization that it was synchrotron radiation emitted by relativistic electrons trapped in the planet's radiation belts. These synchrotron emissions were used to estimate the number and energy of the electrons around Jupiter and led to improved estimates of the magnetic moment and its tilt.

By 1973 the magnetic moment was known within a factor of two, whereas the tilt was correctly estimated at about 10°. The modulation of Jupiter's DAM by Io (the so-called Io-DAM) was discovered in 1964, and allowed Jupiter's rotation period to be precisely determined. The definitive discovery of the Jovian magnetic field occurred in December 1973, when the Pioneer 10 spacecraft flew near the planet.

Exploration after 1970

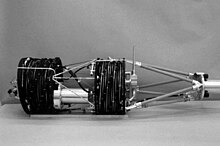

As of 2009 a total of eight spacecraft have flown around Jupiter and all have contributed to the present knowledge of the Jovian magnetosphere. The first space probe to reach Jupiter was Pioneer 10 in December 1973, which passed within 2.9 RJ from the center of the planet. Its twin Pioneer 11 visited Jupiter a year later, traveling along a highly inclined trajectory and approaching the planet as close as 1.6 RJ.

Pioneer 10 provided the best coverage available of the inner magnetic field as it passed through the inner radiation belts within 20 RJ, receiving an integrated dose of 200,000 rads from electrons and 56,000 rads from protons (for a human, a whole body dose of 500 rads would be fatal). The level of radiation at Jupiter was ten times more powerful than Pioneer's designers had predicted, leading to fears that the probe would not survive; however, with a few minor glitches, it managed to pass through the radiation belts, saved in large part by the fact that Jupiter's magnetosphere had "wobbled" slightly upward at that point, moving away from the spacecraft. However, Pioneer 11 did lose most images of Io, as the radiation had caused its imaging photo polarimeter to receive a number of spurious commands. The subsequent and far more technologically advanced Voyager spacecraft had to be redesigned to cope with the massive radiation levels.

Voyagers 1 and 2 arrived at Jupiter in 1979–1980 and traveled almost in its equatorial plane. Voyager 1, which passed within 5 RJ from the planet's center, was first to encounter the Io plasma torus. It received a radiation dosage one thousand times the lethal level for humans, the damage resulting in serious degradation of some high-resolution images of Io and Ganymede. Voyager 2 passed within 10 RJ and discovered the current sheet in the equatorial plane. The next probe to approach Jupiter was Ulysses in 1992, which investigated the planet's polar magnetosphere.

The Galileo spacecraft, which orbited Jupiter from 1995 to 2003, provided a comprehensive coverage of Jupiter's magnetic field near the equatorial plane at distances up to 100 RJ. The regions studied included the magnetotail and the dawn and dusk sectors of the magnetosphere. While Galileo successfully survived in the harsh radiation environment of Jupiter, it still experienced a few technical problems. In particular, the spacecraft's gyroscopes often exhibited increased errors. Several times electrical arcs occurred between rotating and non-rotating parts of the spacecraft, causing it to enter safe mode, which led to total loss of the data from the 16th, 18th and 33rd orbits. The radiation also caused phase shifts in Galileo's ultra-stable quartz oscillator.

When the Cassini spacecraft flew by Jupiter in 2000, it conducted coordinated measurements with Galileo. New Horizons passed close to Jupiter in 2007, carrying out a unique investigation of the Jovian magnetotail, traveling as far as 2500 RJ along its length. In July 2016 Juno was inserted into Jupiter orbit, its scientific objectives include exploration of Jupiter's polar magnetosphere. The coverage of Jupiter's magnetosphere remains much poorer than for Earth's magnetic field. Further study is important to further understand the Jovian magnetosphere's dynamics.

In 2003, NASA conducted a conceptual study called "Human Outer Planets Exploration" (HOPE) regarding the future human exploration of the outer Solar System. The possibility was mooted of building a surface base on Callisto, because of the low radiation levels at the moon's distance from Jupiter and its geological stability. Callisto is the only one of Jupiter's Galilean satellites for which human exploration is feasible. The levels of ionizing radiation on Io, Europa and Ganymede are inimical to human life, and adequate protective measures have yet to be devised.

Exploration after 2010

The Juno New Frontiers mission to Jupiter was launched in 2011 and arrived at Jupiter in 2016. It includes a suite of instruments designed to better understand the magnetosphere, including a magnetometer as well as other devices such as a detector for plasma and radio waves called Waves.

The Jovian Auroral Distributions Experiment (JADE) instrument should also help to understand the magnetosphere.

A primary objective of the Juno mission is to explore the polar magnetosphere of Jupiter. While Ulysses briefly attained latitudes of ~48 degrees, this was at relatively large distances from Jupiter (~8.6 RJ). Hence, the polar magnetosphere of Jupiter is largely uncharted territory and, in particular, the auroral acceleration region has never been visited. ...

— A Wave Investigation for the Juno Mission to Jupiter

Juno revealed a planetary magnetic field rich in spatial variation, possibly due to a relatively large dynamo radius. The most surprising observation until late 2017 was the absence of the expected magnetic signature of intense field aligned currents (Birkeland currents) associated with the main aurora.

One of the goals of the European Space Agency's Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE) mission, launched April, 2023, is to understand the magnetic field from Ganymede and how it impacts Jupiter. Tianwen-4 is a proposed Chinese mission that will either explore the moon Callisto or gather more information on Io.

Notes

- ^ The magnetic moment is proportional to the product of the equatorial field strength and cube of Jupiter's radius, which is 11 times larger than that of the Earth.

- ^ The direct current in the Jovian magnetosphere is not to be confused with the direct current used in electrical circuits. The latter is the opposite of the alternating current.

- ^ The Jovian ionosphere is another significant source of protons.

- ^ The non-Io-DAM is much weaker than the Io-DAM, and is the high-frequency tail of the HOM emissions.

- ^ A Lorentz resonance is one that exists between a particle's orbital speed and the rotation period of a planet's magnetosphere. If the ratio of their angular frequencies is m:n (a rational number) then scientists call it an m:n Lorentz resonance. So, in the case of a 3:2 resonance, a particle at a distance of about 1.71 RJ from Jupiter makes three revolutions around the planet, while the planet's magnetic field makes two revolutions.

- ^ Technically, the flow is "sub-fast", meaning slower than the fast magnetosonic mode. The flow is faster than the acoustic sound speed.

- ^ Pioneer 10 carried a helium vector magnetometer, which measured the magnetic field of Jupiter directly. The spacecraft also made observations of plasma and energetic particles.

References

- ^ Smith, 1974

- ^ Khurana, 2004, pp. 3–5

- ^ Russel, 1993, p. 694

- ^ Zarka, 2005, pp. 375–377

- ^ Blanc, 2005, p. 238 (Table III)

- ^ Khurana, 2004, pp. 1–3

- ^ Khurana, 2004, pp. 5–7

- ^ Bolton, 2002

- ^ Bhardwaj, 2000, p. 342

- ^ Khurana, 2004, pp. 12–13

- ^ Kivelson, 2005, pp. 303–313

- ^ Connerney, J. E. P.; Kotsiaros, S.; Oliversen, R.J.; Espley, J.R.; Joergensen, J. L.; Joergensen, P.S.; Merayo, J. M. G.; Herceg, M.; Bloxham, J.; Moore, K.M.; Bolton, S. J.; Levin, S. M. (2017-05-26). "A New Model of Jupiter's Magnetic Field From Juno's First Nine Orbits" (PDF). Geophysical Research Letters. 45 (6): 2590–2596. Bibcode:2018GeoRL..45.2590C. doi:10.1002/2018GL077312.

- ^ Connerney, J. E. P.; Adriani, A.; Allegrini, F.; Bagenal, F.; Bolton, S. J.; Bonfond, B.; Cowley, S. W. H.; Gerard, J.-C.; Gladstone, G. R. (2017-05-26). "Jupiter's magnetosphere and aurorae observed by the Juno spacecraft during its first polar orbits". Science. 356 (6340): 826–832. Bibcode:2017Sci...356..826C. doi:10.1126/science.aam5928. hdl:2268/211119. PMID 28546207.

- ^ Bolton, S. J.; Adriani, A.; Adumitroaie, V.; Allison, M.; Anderson, J.; Atreya, S.; Bloxham, J.; Brown, S.; Connerney, J. E. P. (2017-05-26). "Jupiter's interior and deep atmosphere: The initial pole-to-pole passes with the Juno spacecraft" (PDF). Science. 356 (6340): 821–825. Bibcode:2017Sci...356..821B. doi:10.1126/science.aal2108. PMID 28546206.

- ^ Agle, DC (May 20, 2019). "NASA's Juno Finds Changes in Jupiter's Magnetic Field". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved June 4, 2019.

- ^ Moore, K. M.; et al. (May 2019). "Time variation of Jupiter's internal magnetic field consistent with zonal wind advection" (PDF). Nature Astronomy. 3 (8): 730–735. Bibcode:2019NatAs...3..730M. doi:10.1038/s41550-019-0772-5. S2CID 182074098.

- ^ "NASA's Juno Finds Changes in Jupiter's Magnetic Field". Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

- ^ Russel, 1993, pp. 715–717

- ^ Russell, 2001, pp. 1015–1016

- ^ Krupp, 2004, pp. 15–16

- ^ Russel, 1993, pp. 725–727

- ^ Khurana, 2004, pp. 17–18

- ^ Krupp, 2004, pp. 3–4

- ^ Krupp, 2004, pp. 4–7

- ^ Krupp, 2004, pp. 1–3

- ^ Khurana, 2004, pp. 13–16

- ^ Khurana, 2004, pp. 10–12

- ^ Russell, 2001, pp. 1024–1025

- ^ Khurana, 2004, pp. 20–21

- ^ Wolverton, 2004, pp. 100–157

- ^ Russell, 2001, pp. 1021–1024

- ^ Kivelson, 2005, pp. 315–316

- ^ Blanc, 2005, pp. 250–253

- ^ Cowley, 2001, pp. 1069–76

- ^ Blanc, 2005, pp. 254–261

- ^ Cowley, 2001, pp. 1083–87

- ^ Russell, 2008

- ^ Krupp, 2007, p. 216

- ^ Krupp, 2004, pp. 7–9

- ^ Krupp, 2004, pp. 11–14

- ^ Khurana, 2004, pp. 18–19

- ^ Russell, 2001, p. 1011

- ^ Nichols, 2006, pp. 393–394

- ^ Krupp, 2004, pp. 18–19

- ^ Nichols, 2006, pp. 404–405

- ^ Elsner, 2005, pp. 419–420

- ^ Bhardwaj, 2000, Tables 2 and 5

- ^ Palier, 2001, pp. 1171–73

- ^ Bhardwaj, 2000, pp. 311–316

- ^ Cowley, 2003, pp. 49–53

- ^ Bhardwaj, 2000, pp. 316–319

- ^ Bhardwaj, 2000, pp. 306–311

- ^ Bhardwaj, 2000, p. 296

- ^ Miller Aylward et al. 2005, pp. 335–339.

- ^ Clarke, 2002

- ^ Blanc, 2005, pp. 277–283

- ^ Redd, Nola Taylor (April 5, 2018). "Scientists Spot the Ghostly Aurora Footprint of Jupiter's Moon Callisto". space.com. Retrieved June 4, 2019.

- ^ Bhattacharyya, Dolon; et al. (January 3, 2018). "Evidence for Auroral Emissions From Callisto's Footprint in HST UV Images". Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics. 123 (1): 364–373. Bibcode:2018JGRA..123..364B. doi:10.1002/2017JA024791. hdl:2268/217988. S2CID 135188023.

- ^ Palier, 2001, pp. 1170–71

- ^ Zarka, 1998, pp. 20,160–168

- ^ Zarka, 1998, pp. 20, 173–181

- ^ Hill, 1995

- ^ Zarka, 2005, pp. 371–375

- ^ Santos-Costa, 2001

- ^ Zarka, 2005, pp. 384–385

- ^ Krupp, 2004, pp. 17–18

- ^ Kivelson, 2004, pp. 2–4

- ^ Johnson, 2004, pp. 1–2

- ^ Johnson, 2004, pp. 3–5

- ^ Burns, 2004, pp. 1–2

- ^ Burns, 2004, pp. 12–14

- ^ Burns, 2004, pp. 10–11

- ^ Burns, 2004, pp. 17–19

- ^ Ringwald, Frederick A. (29 February 2000). "SPS 1020 (Introduction to Space Sciences)". California State University, Fresno. Archived from the original on 25 July 2008. Retrieved 5 January 2014.

- ^ Kivelson, 2004, pp. 8–10

- ^ Kivelson, 2004, pp. 1–2

- ^ Cooper, 2001, pp. 137,139

- ^ Kivelson, 2004, pp. 10–11

- ^ Kivelson, 2004, pp. 16–18

- ^ Williams, 1998, p. 1

- ^ Cooper, 2001, pp. 154–156

- ^ Johnson, 2004, pp. 15–19

- ^ Hibbitts, 2000, p. 1

- ^ Johnson, 2004, pp. 8–13

- ^ Burke and Franklin, 1955

- ^ Drake, 1959

- ^ Hunt, Garry; et al. (1981). Jupiter (1st ed.). London: Rand McNally. ISBN 978-0-528-81542-3.

- ^ Wilson, Andrew (1987). Solar System Log (1st ed.). London: Jane's Publishing Company Limited. ISBN 978-0-7106-0444-6.

- ^ Fieseler, 2002

- ^ "Juno Science Objectives". University of Wisconsin-Madison. Archived from the original on October 16, 2008. Retrieved October 13, 2008.

- ^ Troutman, 2003

- ^ "NASA's Juno and JEDI: Ready to Unlock Mysteries of Jupiter". Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory. June 29, 2016. Archived from the original on March 24, 2017. Retrieved February 7, 2017.

- ^ Kurth, W. S.; Kirchner, D. L.; Hospodarsky, G. B.; Gurnett, D. A.; Zarka, P.; Ergun, R.; Bolton, S. (2008). "A Wave Investigation for the Juno Mission to Jupiter". AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts. 2008: SM41B–1680. Bibcode:2008AGUFMSM41B1680K.

- ^ Connerney, JEP; Adriani, A; Allegrini, F; Bagenal, F; Bolton, SJ; Bonfond, B; Cowley, SWH; Gerard, JC; Gladstone, GR; Grodent, D; Hospodarsky, G; Jorgensen, JL; Kurth, WS; Levin, SM; Mauk, B; McComas, DJ; Mura, A; Paranicas, C; Smith, EJ; Thorne, RM; Valek, P; Waite, J (2017). "Jupiter's magnetosphere and aurorae observed by the Juno spacecraft during its first polar orbits". Science. 356 (6340): 826–832. Bibcode:2017Sci...356..826C. doi:10.1126/science.aam5928. hdl:2381/40230. PMID 28546207.

Cited sources

- Bhardwaj, A.; Gladstone, G.R. (2000). "Auroral emissions of the giant planets". Reviews of Geophysics. 38 (3): 295–353. Bibcode:2000RvGeo..38..295B. doi:10.1029/1998RG000046.

- Blanc, M.; Kallenbach, R.; Erkaev, N. V. (2005). "Solar System magnetospheres". Space Science Reviews. 116 (1–2): 227–298. Bibcode:2005SSRv..116..227B. doi:10.1007/s11214-005-1958-y. S2CID 122318569.

- Bolton, S.J.; Janssen, M.; et al. (2002). "Ultra-relativistic electrons in Jupiter's radiation belts". Nature. 415 (6875): 987–991. Bibcode:2002Natur.415..987B. doi:10.1038/415987a. PMID 11875557.

- Burke, B. F.; Franklin, K. L. (1955). "Observations of a variable radio source associated with the planet Jupiter". Journal of Geophysical Research. 60 (2): 213–217. Bibcode:1955JGR....60..213B. doi:10.1029/JZ060i002p00213.

- Burns, J. A.; Simonelli, D. P.; Showalter; Hamilton; Porco; Throop; Esposito (2004). "Jupiter's ring-moon system" (PDF). In Bagenal, Fran; Dowling, Timothy E.; McKinnon, William B. (eds.). Jupiter: The Planet, Satellites and Magnetosphere. Cambridge University Press. p. 241. Bibcode:2004jpsm.book..241B. ISBN 978-0-521-81808-7.

- Clarke, J.T.; Ajello, J.; et al. (2002). "Ultraviolet emissions from the magnetic footprints of Io, Ganymede and Europa on Jupiter" (PDF). Nature. 415 (6875): 997–1000. Bibcode:2002Natur.415..997C. doi:10.1038/415997a. hdl:2027.42/62861. PMID 11875560. S2CID 4431282.

- Cooper, J. F.; Johnson, R. E.; et al. (2001). "Energetic ion and electron irradiation of the icy Galilean satellites" (PDF). Icarus. 139 (1): 133–159. Bibcode:2001Icar..149..133C. doi:10.1006/icar.2000.6498. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-02-25.

- Cowley, S.W. H.; Bunce, E. J. (2001). "Origin of the main auroral oval in Jupiter's coupled magnetosphere–ionosphere system". Planetary and Space Science. 49 (10–11): 1067–66. Bibcode:2001P&SS...49.1067C. doi:10.1016/S0032-0633(00)00167-7.

- Cowley, S.W. H.; Bunce, E. J. (2003). "Modulation of Jovian middle magnetosphere currents and auroral precipitation by solar wind-induced compressions and expansions of the magnetosphere: initial response and steady state". Planetary and Space Science. 51 (1): 31–56. Bibcode:2003P&SS...51...31C. doi:10.1016/S0032-0633(02)00130-7.

- Drake, F. D.; Hvatum, S. (1959). "Non-thermal microwave radiation from Jupiter". Astronomical Journal. 64: 329. Bibcode:1959AJ.....64S.329D. doi:10.1086/108047.

- Elsner, R. F.; Ramsey, B. D.; et al. (2005). "X-ray probes of magnetospheric interactions with Jupiter's auroral zones, the Galilean satellites, and the Io plasma torus" (PDF). Icarus. 178 (2): 417–428. Bibcode:2005Icar..178..417E. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2005.06.006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-20.

- Fieseler, P.D.; Ardalan, S. M.; et al. (2002). "The radiation effects on Galileo spacecraft systems at Jupiter" (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Nuclear Science. 49 (6): 2739–58. Bibcode:2002ITNS...49.2739F. doi:10.1109/TNS.2002.805386. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-19.

- Hill, T. W.; Dessler, A. J. (1995). "Space physics and astronomy converge in exploration of Jupiter's Magnetosphere". Earth in Space. 8 (32): 6. Bibcode:1995EOSTr..76..313H. doi:10.1029/95EO00190. Archived from the original on 1997-05-01.

- Hibbitts, C.A.; McCord, T.B.; Hansen, T.B. (2000). "Distribution of CO2 and SO2 on the surface of Callisto". Journal of Geophysical Research. 105 (E9): 22, 541–557. Bibcode:2000JGR...10522541H. doi:10.1029/1999JE001101.

- Johnson, R. E.; Carlson, R. V.; et al. (2004). "Radiation Effects on the Surfaces of the Galilean Satellites" (PDF). In Bagenal, Fran; Dowling, Timothy E.; McKinnon, William B. (eds.). Jupiter: The Planet, Satellites and Magnetosphere. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-81808-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-04-30. Retrieved 2009-03-31.

- Khurana, K. K.; Kivelson, M. G.; et al. (2004). "The configuration of Jupiter's magnetosphere" (PDF). In Bagenal, Fran; Dowling, Timothy E.; McKinnon, William B. (eds.). Jupiter: The Planet, Satellites and Magnetosphere. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-81808-7.

- Kivelson, M.G. (2005). "The current systems of the Jovian magnetosphere and ionosphere and predictions for Saturn" (PDF). Space Science Reviews. 116 (1–2): 299–318. Bibcode:2005SSRv..116..299K. doi:10.1007/s11214-005-1959-x. S2CID 17740545.

- Kivelson, M. G.; Bagenal, Fran; et al. (2004). "Magnetospheric interactions with satellites" (PDF). In Bagenal, Fran; Dowling, Timothy E.; McKinnon, William B. (eds.). Jupiter: The Planet, Satellites and Magnetosphere. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-81808-7.

- Krupp, N.; Vasyliunas, V. M.; et al. (2004). "Dynamics of the Jovian Magnetosphere" (PDF). In Bagenal, Fran; Dowling, Timothy E.; McKinnon, William B. (eds.). Jupiter: The Planet, Satellites and Magnetosphere. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-81808-7.

- Krupp, N. (2007). "New surprises in the largest magnetosphere of Our Solar System" (PDF). Science. 318 (5848): 216–217. Bibcode:2007Sci...318..216K. doi:10.1126/science.1150448. PMID 17932281. S2CID 10278419. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-02-23.

- Miller, Steve; Aylward, Alan; Millward, George (January 2005). "Giant Planet Ionospheres and Thermospheres: The Importance of Ion-Neutral Coupling". Space Science Reviews. 116 (1–2): 319–343. Bibcode:2005SSRv..116..319M. doi:10.1007/s11214-005-1960-4. S2CID 119906560.

- Nichols, J. D.; Cowley, S. W. H.; McComas, D. J. (2006). "Magnetopause reconnection rate estimates for Jupiter's magnetosphere based on interplanetary measurements at ~5 AU". Annales Geophysicae. 24 (1): 393–406. Bibcode:2006AnGeo..24..393N. doi:10.5194/angeo-24-393-2006. S2CID 55587210.

- Palier, L.; Prangé, Renée (2001). "More about the structure of the high latitude Jovian aurorae". Planetary and Space Science. 49 (10–11): 1159–73. Bibcode:2001P&SS...49.1159P. doi:10.1016/S0032-0633(01)00023-X.

- Russell, C.T. (1993). "Planetary Magnetospheres" (PDF). Reports on Progress in Physics. 56 (6): 687–732. Bibcode:1993RPPh...56..687R. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/56/6/001. S2CID 250897924.

- Russell, C.T. (2001). "The dynamics of planetary magnetospheres". Planetary and Space Science. 49 (10–11): 1005–1030. Bibcode:2001P&SS...49.1005R. doi:10.1016/S0032-0633(01)00017-4.

- Russell, C.T.; Khurana, K.K.; Arridge, C.S.; Dougherty, M.K. (2008). "The magnetospheres of Jupiter and Saturn and their lessons for the Earth" (PDF). Advances in Space Research. 41 (8): 1310–18. Bibcode:2008AdSpR..41.1310R. doi:10.1016/j.asr.2007.07.037. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-15. Retrieved 2009-03-25.

- Santos-Costa, D.; Bourdarie, S.A. (2001). "Modeling the inner Jovian electron radiation belt including non-equatorial particles". Planetary and Space Science. 49 (3–4): 303–312. Bibcode:2001P&SS...49..303S. doi:10.1016/S0032-0633(00)00151-3.

- Smith, E. J.; Davis, L. Jr.; et al. (1974). "The Planetary Magnetic Field and Magnetosphere of Jupiter: Pioneer 10". Journal of Geophysical Research. 79 (25): 3501–13. Bibcode:1974JGR....79.3501S. doi:10.1029/JA079i025p03501.

- Troutman, P.A.; Bethke, K.; et al. (28 January 2003). "Revolutionary concepts for Human Outer Planet Exploration (HOPE)". AIP Conference Proceedings. 654: 821–828. Bibcode:2003AIPC..654..821T. doi:10.1063/1.1541373. hdl:2060/20030063128. S2CID 109235313.

- Williams, D.J.; Mauk, B.; McEntire, R. W. (1998). "Properties of Ganymede's magnetosphere as revealed by energetic particle observations". Journal of Geophysical Research. 103 (A8): 17, 523–534. Bibcode:1998JGR...10317523W. doi:10.1029/98JA01370.

- Wolverton, M. (2004). The Depths of Space. Joseph Henry Press. ISBN 978-0-309-09050-6.

- Zarka, P.; Kurth, W. S. (1998). "Auroral radio emissions at the outer planets: Observations and theory". Journal of Geophysical Research. 103 (E9): 20, 159–194. Bibcode:1998JGR...10320159Z. doi:10.1029/98JE01323.

- Zarka, P.; Kurth, W. S. (2005). "Radio wave emissions from the outer planets before Cassini". Space Science Reviews. 116 (1–2): 371–397. Bibcode:2005SSRv..116..371Z. doi:10.1007/s11214-005-1962-2. S2CID 85508751.

Further reading

- Carr, Thomas D.; Gulkis, Samuel (1969). "The magnetosphere of Jupiter". Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 7 (1): 577–618. Bibcode:1969ARA&A...7..577C. doi:10.1146/annurev.aa.07.090169.003045.

- Edwards, T.M.; Bunce, E.J.; Cowley, S.W.H. (2001). "A note on the vector potential of Connerney et al.'s model of the equatorial current sheet in Jupiter's magnetosphere". Planetary and Space Science. 49 (10–11): 1115–23. Bibcode:2001P&SS...49.1115E. doi:10.1016/S0032-0633(00)00164-1.

- Gladstone, G.R.; Waite, J.H.; Grodent, D. (2002). "A pulsating auroral X-ray hot spot on Jupiter" (PDF). Nature. 415 (6875): 1000–03. Bibcode:2002Natur.415.1000G. doi:10.1038/4151000a. PMID 11875561.

- Kivelson, Margaret G.; Khurana, Krishan K.; Walker, Raymond J. (2002). "Sheared magnetic field structure in Jupiter's dusk magnetosphere: Implications for return currents" (PDF). Journal of Geophysical Research. 107 (A7): 1116. Bibcode:2002JGRA..107.1116K. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.424.7769. doi:10.1029/2001JA000251.

- Kivelson, M.G. (2005). "Transport and acceleration of plasma in the magnetospheres of Earth and Jupiter and expectations for Saturn" (PDF). Advances in Space Research. 36 (11): 2077–89. Bibcode:2005AdSpR..36.2077K. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.486.8721. doi:10.1016/j.asr.2005.05.104.

- Kivelson, Margaret G.; Southwood, David J. (2003). "First evidence of IMF control of Jovian magnetospheric boundary locations: Cassini and Galileo magnetic field measurements compared" (PDF). Planetary and Space Science. 51 (A7): 891–98. Bibcode:2003P&SS...51..891K. doi:10.1016/S0032-0633(03)00075-8.

- McComas, D.J.; Allegrini, F.; Bagenal, F.; et al. (2007). "Diverse Plasma Populations and Structures in Jupiter's Magnetotail". Science. 318 (5848): 217–20. Bibcode:2007Sci...318..217M. doi:10.1126/science.1147393. PMID 17932282. S2CID 21032193.

- Maclennan, G.G.; Maclennan, L.J.; Lagg, Andreas (2001). "Hot plasma heavy ion abundance in the inner Jovian magnetosphere (<10 Rj)". Planetary and Space Science. 49 (3–4): 275–82. Bibcode:2001P&SS...49..275M. doi:10.1016/S0032-0633(00)00148-3.

- Russell, C.T.; Yu, Z.J.; Kivelson, M.G. (2001). "The rotation period of Jupiter" (PDF). Geophysical Research Letters. 28 (10): 1911–12. Bibcode:2001GeoRL..28.1911R. doi:10.1029/2001GL012917.

- Zarka, Philippe; Queinnec, Julien; Crary, Frank J. (2001). "Low-frequency limit of Jovian radio emissions and implications on source locations and Io plasma wake". Planetary and Space Science. 49 (10–11): 1137–49. Bibcode:2001P&SS...49.1137Z. doi:10.1016/S0032-0633(01)00021-6.