Khalij (Cairo)

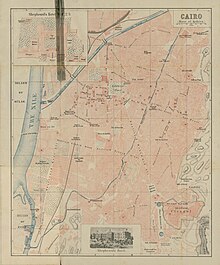

In the 14th century, the Mamluk sultan al-Nasir Muhammad created a second canal further west, the Khalij al-Nasiri, which was linked to the main canal. In the 1890s, as its function became less essential, the Khalij was filled in and converted into what is now Port Said Street in central Cairo.

History

Origins

An ancient canal linking the Nile with the Red Sea had previously existed in the region since the Pharaonic period, probably begun in the reign of Necho II (r. 610–595 BC). The canal was re-dug by the Persian king Darius (r. 521–486 BC). It was last restored by Roman emperor Trajan, who moved its mouth on the Nile further south, to what is now Old Cairo, and named it Amnis Traianus or Traianos potamos (lit. 'Trajan's River') after himself. Remains of the massive stone walls that made up the entrance to Trajan's canal have been found under the present-day Coptic Church of Saint Sergius and the Coptic Church of Saint George. Where the canal joined the Nile, Trajan constructed a harbor and fortifications. In the third century AD, Diocletian expanded the fortifications and constructed the Babylon Fortress at the mouth of the canal. The canal was difficult to maintain and by the time of the Arab conquest in 641 AD, it had fallen out of use and into disrepair.

Shortly after the conquest, the commander of the Muslim force, Amr ibn al-As, ordered that the canal, which had silted up in the meantime, be re-excavated, perhaps at the request of the Caliph Umar (r. 634–644 AD), in order to more efficiently transport grain from Egypt to Medina (the capital of the new Islamic caliphate). The new canal dug by Amr was excavated further north, joining the Nile close to what is now the Sayyida Zaynab neighbourhood of Cairo. The mouth of Trajan's canal was instead covered by the new Islamic city of Fustat, where the Arabs had perhaps already settled by the time the canal project was initiated. In honour of Umar, the new canal became known as Khalij Amir al-Mu'minin ("Canal of the Leader of the Faithful"). A bridge was built over the canal in 688 for one of the two main north–south roads of Fustat, al-Tariq ("the Way").

In medieval Cairo

The new canal was not successful in the long term. It was eventually closed, either around 750 during the Abbasid Revolution that toppled the Umayyads, or in 767–768 on the orders of the Abbasid caliph al-Mansur, who wanted to prevent supplies from reaching a rebellion in Medina. The waters at the end of the closed canal pooled and formed the Birkat al-Hajj ("Pond of the Pilgrimage"), a body of water to the northeast of Cairo. Its name referred to the fact that it became the first station on the pilgrimage (Hajj) journey from Egypt to Mecca. The canal itself later became known as the Khalij al-Misri or Khalij al-Masri. Thenceforth, its function was primarily to provide water for Cairo and to irrigate the area to the north of the city.

Al-Askar and al-Qata'i, two administrative capitals founded north of Fustat in the 8th and 9th centuries, were both built along the banks of the canal. During the Ikhshidid dynasty (935–969), gardens and a large polo field were located along its banks. When the Fatimids founded their new capital of al-Qahira (Cairo) in 969, the Khalij marked the western boundary of the new city. Most of the major north-south streets of historic Cairo, including the main avenue known today as al-Mu'izz Street, were oriented to run parallel with the canal. The location of the canal's entrance on the Nile became known as Fumm al-Khalij ("mouth of the canal").

It became a standard practice to close and reopen the canal every year. In the early era of the Khalij, when the water level of the Nile was higher, the canal was navigable year-round and a dike was built during the annual floods to restrain the waters. In later centuries, when the area became drier, the process took place in reverse; a dike was built for most of the year and then opened during flood season. By the Ottoman period, it was bringing water into the city for about three months a year.

The yearly opening of the canal was a practice that according to some modern scholars echoes rituals of pre-Islamic or even Pharaonic times. Known as the Festival of the Opening of the Canal (fath al-khalij), this became an event that was attended with great pomp by the Fatimid caliphs. Before the Fatimids, it was celebrated further north, at Ayn Shams, and was likely relocated to the Khalij as part of the establishment of Cairo as the new capital. The ceremony took place two or three days after the ceremonial 'anointing of the Nilometer' (Takhliq al-Miqyas) on the nearby Roda Island, which occurred when the Nile waters reached 16 cubits in height, guaranteeing a sufficient harvest. These festivities, marking the arrival of the Nile floods, maintained their importance for centuries. It was one of the most important and spectacular events in the annual calendar of pre-modern Cairo and many historical accounts written by travelers to the city describe it. The ceremonies continued to be attended by the later sultans of Egypt or by their high-ranking officials.

The small strip of land between the western city wall of Cairo and the Khalij was occupied by gardens or used by the population for leisure activities, particularly during the Nile floods, when the canal carried water; the Fatimid caliph al-Aziz (r. 975–996) built the pleasure pavilion al-Lu'lu'a ('the pearl'), from where he could observe the boat races and other water sports. His successor, al-Hakim (r. 996–1025) re-dug the canal, at least for the portion next to Cairo, and named it after himself as al-khalij al-Hakimi. Over time, the course of the Nile shifted further west, which opened up more and more land for development on this side of the city. During the reign of the Ayyubid sultan Salah ad-Din (r. 1174–1193), the Muski Bridge was built over the canal sometime before 1188 as part of various road improvements. More bridges were built in the following Mamluk period (13th to early 16th centuries). Sultan Baybars (r. 1260–1277) built the Bridge of the Lions (Qanatir al-Siba'), which was restored by Sultan al-Nasir Muhammad in 1331. The Amir Husayn Bridge was built circa 1319, the Aqsunqur Bridge prior to 1339, and the Tuquzdamur Bridge prior to 1345.

Addition of the Khalij al-Nasiri

More significantly, al-Nasir Muhammad initiated the construction of a new canal in 1325. This was initially known as the Khalij al-Nasiri ("Canal of al-Nasir") but later became known also as the Khalij al-Maghribi ("Western Canal"). It was dug about 1200 metres northwest of the old canal, branching from the Nile at Mawridat al-Balat, opposite the northern tip of Roda Island, running north roughly parallel to the old canal, before joining the latter near the al-Zahir Baybars Mosque in the northern Husayniya district of Cairo. Al-Nasir entrusted the construction to Amir Arghun and work lasted around two months, from 15 April to 12 June 1325. A corvée of peasants were forced to provide the necessary manual labour.

Multiple factors may have motivated the construction of the new canal. Al-Nasir had built a new palace and a khanqah at Siryaqus, a place north of Cairo, and his canal was to supply these with water and make them accessible from the Nile. It likely also served to supplement the old canal, which was prone to silting up. The new canal was built along the low-lying land that was once the bed of the Nile (before it shifted), thus helping to drain this area.

This project had an important long-term effect on the city's geography and in encouraging its growth. The land west of the old Khalij, now made more habitable, was shortly converted into orchards, gardens, and villas. It was also marked by multiple large ponds (birkas). Al-Nasir Muhammad actively encouraged his amirs (high-ranking officials) to develop and settle the area. Nonetheless, it remained only sparsely inhabited and the old Khalij continued to mark the effective western boundary of the city until the end of the Mamluk period.

Among other water infrastructure built under Mamluk rule was an aqueduct to provide water to the Cairo Citadel. The aqueduct was begun by al-Nasir Muhammad and later expanded by al-Ghuri (r. 1501–1516). Its water intake tower, a large hexagonal structure, still stands today and is located near the mouth of the original Khalij on the Nile.

Later history

It was only during the Ottoman period (16th to 19th centuries) that the west bank of the old Khalij progressively urbanized. During this time, the notables and elites of Cairo built mansions along its shores as well as around the small lake known as Birkat al-Fil and the areas further south. The western outskirts near the Khalij thus became the more affluent districts of the city. This turned the canal into a more central artery of Cairo. The Khalij al-Nasiri became the general western boundary of the city instead.

By the 19th century, the Khalij's importance had greatly diminished as year-round irrigation became common. As the area became more desiccated over time, the canal also became an unattractive feature and a potential source of disease. The people of the city used it as a dumping ground for garbage. When the waters retreated every year, it became a stagnant ditch. By this period, the canal also did not extend further than what is now the al-Daher district in northern Cairo. Based on old photographs, it was less than 10 metres (33 ft) wide.

- 19th-century illustrations of the Khalij

-

Depiction of a bridge over the Khalij in the Description de l'Égypte (c. 1809)

-

Illustration of houses along the Khalij in the early 19th century (drawing by Pascal Coste)

-

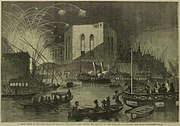

Depiction of the Festival of the Opening of the Canal (c. 1862)

-

19th-century photograph of the Khalij and houses along its banks

As part of his ambitious expansion project for Cairo in the 1860s, Khedive Isma'il excavated a new canal, the Isma'iliyya Canal, which prepared the land further north for development and also provided fresh water for the Suez Canal's construction. In the course of Isma'il's construction projects, the Khalij al-Nasiri was completely filled in and many of the old ponds (birkas) in the area disappeared.

Between 1896 and 1899, the main Khalij itself was filled and converted into a wide boulevard for sanitation reasons and to make way for a tramline to be constructed by the Cairo Tramway Company. The canal was filled in phases: the first phase started in 1897 in the north of Cairo and the last phase finished near Fumm al-Khalig (on the Nile shore) in 1899. The tramline, Cairo's first, began operating by the summer of 1900. The new street was named after the canal, Khalij al-Masri Street (Shari'a el-Khalig el-Masri), until 1957, when it was renamed Port Said Street (Shari'a Bur Sa'id), in honour of that city's resistance to British and French forces during the 1956 Suez Crisis. In 1912, the Isma'iliyya Canal in Cairo was also filled in to make way for further expansion of the city.

Notes

- ^ This Nilometer ceremony was introduced during the tenure of al-Ma'mun al-Bata'ihi as Fatimid vizier in the 1120s.

- ^ Fifteen cubits (1 Arab cubit, subdivided into 24 fingers, equalled 46.2 centimetres (18.2 in)) was the minimum level of flood required in the early Middle Ages for a full harvest that averted famine; sixteen meant a full harvest but still some hardship; seventeen, a bumper harvest; while disastrous flooding was the consequence if the river rose above eighteen cubits.

- ^ Some of the cited sources differ on the exact date, stating that filling occurred or began in either 1896, 1897, or 1898.

References

Citations

- ^ Sheehan 2010, pp. 35–38.

- ^ Raymond 2000, p. 2.

- ^ Raymond 2000, pp. 2, 15–16.

- ^ Halm 2003, p. 25.

- ^ Gabra et al. 2013, p. 21.

- ^ Sheehan 2010, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Raymond 2000, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Raymond 2000, p. 16.

- ^ Sheehan 2010, p. 40.

- ^ Raymond 2000, p. 21.

- ^ Bloom, Jonathan M.; Blair, Sheila S., eds. (2009). "Cairo". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. pp. 321–335. ISBN 9780195309911.

- ^ Abdel Barr, Omniya (2022). "Building Mamluk Cairo: The Capital of a Sultanate". In AlSayyad, Nezar (ed.). Routledge Handbook on Cairo: Histories, Representations and Discourses. Taylor & Francis. p. 56. ISBN 978-1-000-78789-4.

- ^ Abu-Lughod 1971, p. 134.

- ^ Swelim, Tarek (2022). "Al-Qata'i': A Lost City in Cairo – Revisited". In AlSayyad, Nezar (ed.). Routledge Handbook on Cairo: Histories, Representations and Discourses. Routledge. p. 25. ISBN 978-1-000-78789-4.

- ^ Halm 2003, p. 19.

- ^ Raymond 2000, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Rabbat, Nasser (2022). "Coopting the Street: The Urban Character of Mamluk Architecture". In AlSayyad, Nezar (ed.). Routledge Handbook on Cairo: Histories, Representations and Discourses. Routledge. p. 69. ISBN 978-1-000-78789-4.

- ^ Williams, Caroline (2018). Islamic Monuments in Cairo: The Practical Guide (7th ed.). Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press. p. 51. ISBN 9789774168550.

- ^ Sanders, Paula (1994). Ritual, Politics, and the City in Fatimid Cairo. SUNY Press. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-7914-1781-2.

- ^ Raymond 2000, p. 246.

- ^ Halm 2003, p. 67.

- ^ Raymond 2000, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Halm 2003, pp. 64–67.

- ^ Sayyid, Ayman Fouad (2022). "Cairo as a palace: Rituals of the Fatimid Caliphate". In AlSayyad, Nezar (ed.). Routledge Handbook on Cairo: Histories, Representations and Discourses. Routledge. p. 41. ISBN 978-1-000-78789-4.

- ^ Halm 2003, pp. 54–64.

- ^ Halm 2003, pp. 58–60, 68–70.

- ^ Behrens-Abouseif, Doris (2022). "The Earliest Images of Cairo's Islamic Architecture". In AlSayyad, Nezar (ed.). Routledge Handbook on Cairo: Histories, Representations and Discourses. Routledge. p. 176. ISBN 978-1-000-78789-4.

- ^ Halm 2003, p. 26.

- ^ Raymond 2000, p. 125 (and others).

- ^ Raymond 2000, p. 97.

- ^ Raymond 2000, p. 125.

- ^ Raymond 2000, pp. 123–125.

- ^ Abu-Lughod 1971, pp. 35–36.

- ^ Abu-Lughod 1971, p. 36.

- ^ Williams, John Alden (1984). "Urbanization and Monument Construction in Mamluk Cairo". Muqarnas. 2: 36–37. doi:10.2307/1523054. ISSN 0732-2992. JSTOR 1523054.

- ^ Michel, Nicolas (2018). "Cairo, Ottoman". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (3rd ed.). Brill Online. ISSN 1873-9830.

- ^ Abu-Lughod 1971, p. 86.

- ^ Davies, Humphrey (2018). "Bur Sa'id, Share'". A Field Guide to the Street Names of Central Cairo. American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 978-1-61797-915-6.

- ^ Abu-Lughod 1971, p. 103.

- ^ Raymond 2000, p. 312.

- ^ Williams, Caroline (2005). "Nineteenth-Century Images of Cairo: From the Real to the Interpretive". In AlSayyad, Nezar; Bierman, Irene A.; Rabbat, Nasser (eds.). Making Cairo Medieval. Lexington Books. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-7391-5743-5.

- ^ Volait, Mercedes (2017). "Cairo, modern period". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, Three. Brill. ISBN 9789004161658.

- ^ Raymond 2000, p. 326.

Sources

- Abu-Lughod, Janet L. (1971). Cairo: 1001 Years of the City Victorious. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-65660-1.

- Gabra, Gawdat; van Loon, Gertrud J.M.; Reif, Stefan; Swelim, Tarek (2013). Ludwig, Carolyn; Jackson, Morris (eds.). The History and Religious Heritage of Old Cairo: Its Fortress, Churches, Synagogue, and Mosque. American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 9789774167690.

- Halm, Heinz (2003). Die Kalifen von Kairo: Die Fatimiden in Ägypten, 973–1074 [The Caliphs of Cairo: The Fatimids in Egypt, 973–1074] (in German). Munich: C. H. Beck. ISBN 3-406-48654-1.

- Raymond, André (2000) [1993]. Cairo. Translated by Wood, Willard. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-00316-3.

- Sheehan, Peter (2010). Babylon of Egypt: The Archaeology of Old Cairo and the Origins of the City. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-977-416-731-7.