Lagoon Hull

An additional part of the scheme is to create a larger dock area which is protected from wave and tidal action, providing a safe haven for shipping.

History

Severe flooding has affected the City of Hull throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. A tidal surge in 1969 prompted the development of the River Hull tidal surge barrier, which only prevents flooding upstream of the barrier on the River Hull, whereas 90% of the city, and its foreshore environs, is 2 metres (6 ft 7 in) below the spring high-tide line. In the 2013 floods and tidal surge, the barrier at Hull came within centimetres of being overwhelmed, and whilst it prevented major flooding in the city, the Port of Immingham, on the south bank of the estuary, was subjected to flooding.

One of the suggestions to combat this was a barrier across the entire Humber Estuary, which would protect many localities on both sides of the estuary. However, this would need to be four times larger than the Thames Barrier and was costed in 2019 at £10 billion. After the 2013 floods, Members of Parliament and the Local Enterprise Partnership, asked the government for money to shore up the flood defences.

The project for a lagoon was announced in 2019, but had been in development for six years before it was unveiled to the public.

Lagoon proposal

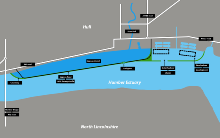

A stone causeway would run from the foreshore at Hessle to Hull docks, creating a lagoon by effectively damming the outlet of the River Hull, which would then become non-tidal. The causeway would be over 11 kilometres (6.8 mi) long, with the newer dual carriageway covering 9.6 kilometres (6 mi), and the resultant lagoon, which would cover 5 square kilometres (1.9 sq mi), would be controlled by floodgates, allowing the water to exit into the Humber Estuary in a controlled manner, thereby acting as a flood defence for the city. This flood defence is labelled as being good enough to keep the city flood free from tidal surges for 100 years. A study in relation to the 2013 flooding determined that were the lagoon to have been in place, it would afforded the city 100% protection and the wider estuary would have seen a reduction in flooding of 80%.

The proposal for the lagoon includes a new section of dual carriageway, that would connect with the A63 road near to the Humber Bridge, and run along the edge of the lagoon avoiding the centre of Hull, and connecting with the A63, the A1165 and the A1033 in the eastern part of Hull near the docks. The proposal for the causeway will include pedestrian access and a cycle lane. East of the lagoon, a new 2-square-kilometre (0.77 sq mi) outer harbour development would also be created providing ease of access by shipping into the docks, and a completely new dock area, which would be protected from the tides and waves. The outer harbour development already has development consent and involves the use of 84 hectares (210 acres) of land. In 2019, the project was costed at £1.5 billion.

Independent analysis of the project by ABPmer, the University of Hull and the Environment Agency, determined that fears around making flooding worse (or creating flooding elsewhere in the estuary), were unfounded. As the estuary is only 6.5 metres (21 ft) deep on average, tidal surges do not work as they do on other river estuaries which are generally deeper. The causeway would actually contribute to less water entering the estuary during a tidal surge.

If sufficient funding were raised, and planning permission were to be granted, the project could only be delivered after feasibility studies were completed (five to ten years) and then a further five years of building would see the project delivered by 2030 at the earliest.

See also

- Bransholme water works, has storage lagoons on the River Hull to regulate the flow of water

- Coastal erosion in Yorkshire

Notes

- ^ Hull suffers from four different types of flooding; pluvial, fluvial, tidal surge and groundwater flooding.

- ^ However, many locations on the waterfront of Hull where it borders the Humber Estuary were inundated. Under the proposed lagoon, these areas would not see a reoccurrence in flooding.

References

- ^ Budoo 2020, p. 34.

- ^ Coulthard, T. J.; Frostick, L. E. (September 2010). "The Hull floods of 2007: implications for the governance and management of urban drainage systems: The Hull floods of 2007". Journal of Flood Risk Management. 3 (3): 223–231. doi:10.1111/j.1753-318X.2010.01072.x. S2CID 129589270.

- ^ "Hull tidal barrier saves city from record 4.9m high tides". BBC News. 28 November 2011. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- ^ Historic England. "Tidal Surge Barrier, River Hull (Grade II) (1446522)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 26 March 2021.

- ^ Walsh, Stephen (3 January 2018). "'Does Hull have a future?' City built on a flood plain faces sea rise reckoning". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- ^ Campbell, James (29 September 2019). "Inside Hull's tidal barrier – and the devastation that inspired it". Hull Live. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- ^ "Humber tidal surge: Trauma of the floods one year on". BBC News. 5 December 2014. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- ^ Winter, Phil (21 November 2019). "Humber tidal barrier would cost 'billions' and take decades to build". Business Live. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- ^ "Hull City Council Flood Investigation Report December 2013 City Centre Tidal Surge Flood Event" (PDF). hull.gov.uk. February 2014. p. 8. Retrieved 15 March 2021.

- ^ Excell, Jon (11 May 2020). "Lagoon Hull: the Humber estuary's ambitious new flood defence scheme". The Engineer. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- ^ Wood, Alexandra (21 February 2019). "The £10bn tidal barrier that could be built to combat climate change". The Yorkshire Post. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- ^ Winn, Philip; Laws, Holly; Marshall, Lucy; Todd, Helen; Normandale, Laura; Hopton, Claire; Brown, Jenny; Connell, Nick (January 2020). "Developing a New Humber Flood Risk Management Strategy to Support People, Business and the Environment". In Handiman, Nick (ed.). Coastal Management 2019. London: Institution of Civil Engineers. p. 29. doi:10.1680/cm.65147.029. ISBN 978-0-7277-6514-7. S2CID 242679357.

- ^ Mitchinson, James, ed. (26 February 2021). "New lagoon 'won't make flooding worse'". The Yorkshire Post. p. 9. ISSN 0963-1496.

- ^ Young, Angus (20 October 2020). "Ambitious £1.5bn Hull lagoon project needs 'people power'". Hull Live. Retrieved 26 February 2021.

- ^ Winter, Phillip (21 November 2019). "Lagoon bosses answer your burning questions – from timesacles to the environmental impact". Hull Daily Mail. pp. 8–9. ISSN 1741-3419.

- ^ "Hull unveils lagoon plans to protect against flooding". BBC News. 24 October 2019. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- ^ Budoo 2020, p. 35.

- ^ "£1.5bn Lagoon Hull project 'will transform the future of our region' | BW Magazine". bw-magazine.co.uk. 25 October 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2021.

- ^ Budoo 2020, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Young, Angus (24 February 2021). "Lagoon Hull project boosted by flood risk findings from Humber". Hull Live. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- ^ Dickinson, Greg (25 October 2019). "Could a giant lagoon turn Hull into 'one of the most exciting waterfront cities in the world'?". The Telegraph. Retrieved 15 March 2021.

- ^ Hatley, Paul (13 December 2019). "Road will be open to all". Hull Daily Mail. p. 14. ISSN 1741-3419.

- ^ Wood, Alexandra (25 October 2019). "£1.5 billion lagoon plan to make Hull 'one of the most exciting waterfront cities in Europe'". The Yorkshire Post. Retrieved 15 March 2021.

- ^ Foy, Simon (13 November 2019). "Hull rides a wave of optimism with lagoon plan". The Daily Telegraph. p. 4. ISSN 0307-1235.

- ^ Young, Angus (24 February 2021). "Lagoon Hull project boosted by flood risk findings from Humber". Hull Live. Retrieved 16 March 2021.

- ^ Budoo 2020, pp. 35–36.

Source

- Budoo, Nadine (September 2020). "Future of Stormwater, Lagoon Hull; Balanced Defence". New Civil Engineer. London: EMAP. ISSN 0307-7683. Archived from the original on 8 August 2023.