Maria Magdalene

The Gospel of Luke chapter 8 lists Mary Magdalene as one of the women who traveled with Jesus and helped support his ministry "out of their resources", indicating that she was probably wealthy. The same passage also states that seven demons had been driven out of her, a statement which is repeated from Mark 16. In all four canonical gospels, Mary Magdalene is a witness to the crucifixion of Jesus and, in the Synoptic Gospels, she is also present at his burial. All four gospels identify her, either alone or as a member of a larger group of women, as the first to witness the empty tomb, and, either alone or as a member of a group, as the first to witness Jesus's resurrection.

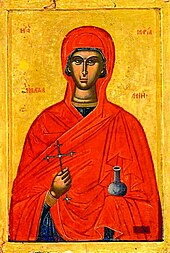

Mary Magdalene is considered to be a saint by the Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Anglican, and Lutheran denominations. In 2016, Pope Francis raised the level of liturgical memory on July 22 from memorial to feast, and for her to be referred to as the "Apostle of the apostles". Some Protestant churches honor her as a heroine of the faith. The Eastern Orthodox churches also commemorate her on the Sunday of the Myrrhbearers, the Orthodox equivalent of one of the Western Three Marys traditions.

Portrayal in Gnostic writings

Because she was the first to witness Jesus's resurrection, Mary Magdalene is known in some Christian traditions as the "apostle to the apostles". She is a central figure in Gnostic Christian writings, including the Dialogue of the Savior, the Pistis Sophia, the Gospel of Thomas, the Gospel of Philip, and the Gospel of Mary. These texts portray her as an apostle, as Jesus's closest and most beloved disciple and the only one who truly understood his teachings. In the Gnostic texts, or Gnostic gospels, Mary's closeness to Jesus results in tension with another disciple, Peter, due to her gender and Peter's envy of the special teachings given to her. In the Gospel of Philip's text, Marvin Meyer's translation says (missing text bracketed): "The companion of the [...] is Mary of Magdala. The [...] her more than [...] the disciples, [...] kissed her often on her [...]."

Life

It is widely accepted among secular historians that, like Jesus, Mary Magdalene was a real historical figure. Nonetheless, very little is known about her life. Unlike Paul the Apostle, Mary Magdalene left behind no known writings of her own. She was never mentioned in any of the Pauline epistles or in any of the general epistles. The earliest and most reliable sources about her life are the three Synoptic Gospels of Mark, Matthew, and Luke, which were all written during the first century AD.

During Jesus's ministry

Mary Magdalene's epithet Magdalene (ἡ Μαγδαληνή; lit. 'the Magdalene') probably means that she came from Magdala, a village on the western shore of the Sea of Galilee that was primarily known in antiquity as a fishing town. Mary was, by far, the most common Jewish given name for girls and women during the first century, so it was necessary for the authors of the gospels to call her Magdalene in order to distinguish her from the other women named Mary who followed Jesus. Although the Gospel of Mark, reputed by scholars to be the earliest surviving gospel, does not mention Mary Magdalene until Jesus's crucifixion, the Gospel of Luke 8:2–3 provides a brief summary of her role during his ministry:

Soon afterwards he went on through cities and villages, proclaiming and bringing the good news of the kingdom of God. The twelve were with him, as well as some women who had been cured of evil spirits and infirmities: Mary, called Magdalene, from whom seven demons had gone out, and Joanna, the wife of Herod's steward Chuza, and Susanna, and many others, who provided for them out of their resources.

— Luke 8:1–3

According to the Gospel of Luke, Jesus exorcised "seven demons" from Mary Magdalene. That seven demons had possessed Mary is repeated in Mark 16:9, part of the "longer ending" of that gospel – this is not found in the earliest manuscripts and is possibly a second-century addition to the original text, possibly based on the Gospel of Luke. In the first century, demons were believed widely to cause physical and psychological illness. Bruce Chilton, a scholar of early Christianity, states that the reference to the number of demons being "seven" may mean that Mary had to undergo seven exorcisms, probably over a long period of time, due to the first six being partially or wholly unsuccessful.

Bart D. Ehrman, a New Testament scholar and historian of early Christianity, contends that the number seven may be merely symbolic, since, in Jewish tradition, seven was the number of completion, so that Mary was possessed by seven demons may simply mean she was completely overwhelmed by their power. In either case, Mary must have suffered from severe emotional or psychological trauma for an exorcism of this kind to have been perceived as necessary. Consequently, her devotion to Jesus resulting from this healing must have been very strong. The Gospels' writers normally relish giving dramatic descriptions of Jesus's public exorcisms, with the possessed person wailing, thrashing, and tearing his or her clothes in front of a crowd. By contrast, that Mary's exorcism receives little attention may indicate that either Jesus performed it privately or that the recorders did not perceive it as particularly dramatic.

Because Mary is listed as one of the women who supported Jesus's ministry financially, she must have been relatively wealthy. The places where she and the other women are mentioned throughout the gospels indicate strongly that they were vital to Jesus's ministry and that Mary Magdalene always appears first, whenever she is listed in the Synoptic Gospels as a member of a group of women, indicates that she was seen as the most important out of all of them. Carla Ricci notes that, in lists of the disciples, Mary Magdalene occupies a similar position among Jesus's female followers as Simon Peter does among the male apostles.

That women played such an active and important role in Jesus's ministry was not entirely radical or even unique; inscriptions from a synagogue in Aphrodisias in Asia Minor from around the same time period reveal that many of the major donors to the synagogue were women. Jesus's ministry did bring women greater liberation than they would typically have held in mainstream Jewish society.

Witness to Jesus's crucifixion and burial

All four canonical gospels agree that several other women watched Jesus's crucifixion from a distance, with three explicitly naming Mary Magdalene as present. Mark 15:40 lists the names of these women as Mary Magdalene; Mary, mother of James; and Salome. Matthew 27:55–56 lists Mary Magdalene, Mary mother of James and Joseph, and the unnamed mother of the sons of Zebedee (who may be the same person Mark calls Salome). Luke 23:49 mentioned a group of women watching the crucifixion, but did not give any of their names. John 19:25 lists Mary, mother of Jesus, her sister, Mary, wife of Clopas, and Mary Magdalene as witnesses to the crucifixion.

Virtually all reputable historians agree that Jesus was crucified by the Romans under the orders of Pontius Pilate. James Dunn states of baptism and crucifixion that these "two facts in the life of Jesus command almost universal assent". Nonetheless, the gospels' accounts of Jesus's crucifixion differ. Ehrman states that the presence of Mary Magdalene and the other women at the cross is probably historical because Christians would have been unlikely to make up that the main witnesses to the crucifixion were women and also because their presence is attested in both the Synoptic Gospels and in the Gospel of John independently. Maurice Casey concurs that the presence of Mary Magdalene and the other women at the crucifixion of Jesus may be recorded as an historical fact. According to E. P. Sanders, the reason why the women watched the crucifixion even after the male disciples had fled may have been because they were less likely to be arrested, they were braver than the men, or some combination thereof.

All four canonical gospels, as well as the apocryphal Gospel of Peter, agree that Jesus's body was taken down from the cross and buried by a man named Joseph of Arimathea. Mark 15:47 lists Mary Magdalene and Mary, mother of Joses as witnesses to the burial of Jesus. Matthew 27:61 lists Mary Magdalene and "the other Mary" as witnesses. Luke 23:55 mentions "the women who had followed him from Galilee", but does not list any of their names. John 19:39–42 does not mention any women present during Joseph's burial of Jesus, but does mention the presence of Nicodemus, a Pharisee with whom Jesus had a conversation near the beginning of the gospel. Ehrman, who previously accepted the story of Jesus's burial as historical, now rejects it as a later invention on the basis that Roman governors almost never allowed for executed criminals to be given any kind of burial and Pontius Pilate in particular was not "the sort of ruler who would break with tradition and policy when kindly asked by a member of the Jewish council to provide a decent burial for a crucified victim". Casey argues that Jesus was given a proper burial by Joseph of Arimathea, noting that, on some very rare occasions, Roman governors did release the bodies of executed prisoners for burial. Nonetheless, he rejects that Jesus could have been interred in an expensive tomb with a stone rolled in front of it like the one described in the gospels, leading him to conclude that Mary and the other women must not have seen the tomb. Sanders affirms Jesus's burial by Joseph of Arimathea in the presence of Mary Magdalene and the other female followers as completely historical.

Resurrection of Jesus

The earliest description of Jesus's post-resurrection appearances is a quotation of a pre-Pauline creed preserved by Paul the Apostle in 1 Corinthians 15:3–8, which was written roughly 20 years before any of the gospels. This passage made no mention of Mary Magdalene, the other women, or the story of the empty tomb, but rather credits Simon Peter with having been the first to see the risen Jesus. Despite this, all four canonical gospels, as well as the apocryphal Gospel of Peter, agreed that Mary Magdalene, either alone or as a member of a group, was the first person to discover that Jesus's tomb was empty. Nonetheless, the details of the accounts differ drastically.

According to Mark 16:1–8, the earliest account of the discovery of the empty tomb, Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of James, and Salome went to the tomb just after sunrise, a day and half after Jesus's burial and found that the stone had already been rolled away. They went inside and saw a young man dressed in white, who told them that Jesus had risen from the dead and instructed them to tell the male disciples that he would meet them in Galilee. Instead, the women ran away and told no one, because they were too afraid. The original text of the gospel ends here, without the resurrected Jesus making an appearance to anyone. Casey argues that the reason for this abrupt ending may be because the Gospel of Mark is an unfinished first draft.

According to Matthew 28:1–10, Mary Magdalene and "the other Mary" went to the tomb. An earthquake occurred and an angel dressed in white descended from Heaven and rolled aside the stone as the women were watching. The angel told them that Jesus had risen from the dead. Then the risen Jesus himself appeared to the women as they were leaving the tomb and told them to tell the other disciples that he would meet them in Galilee.

According to Luke 24:1–12 Mary Magdalene, Joanna, and Mary the mother of James went to the tomb and found the stone already rolled away, as in Mark. They went inside and saw two young men dressed in white who told them that Jesus had risen from the dead. Then they went and told the eleven remaining apostles, who dismissed their story as nonsense. In Luke's account, Jesus never appears to the women, but instead makes his first appearance to Cleopas and an unnamed "disciple" on the road to Emmaus. Luke's narrative also removes the injunction for the women to tell the disciples to return to Galilee and instead has Jesus tell the disciples not to return to Galilee, but rather to stay in the precincts of Jerusalem.

Mary Magdalene's role in the resurrection narrative is greatly increased in the account from the Gospel of John. According to John 20:1–10, Mary Magdalene went to the tomb when it was still dark and saw that the stone had already been rolled away. She did not see anyone, but immediately ran to tell Peter and the "beloved disciple", who came with her to the tomb and confirmed that it was empty, but returned home without seeing the risen Jesus. According to John 20:11–18, Mary, now alone in the garden outside the tomb, saw two angels sitting where Jesus's body had been. Then the risen Jesus approached her. She at first mistook him for the gardener, but, after she heard him say her name, she recognized him and cried out "Rabbouni!" (which is Aramaic for 'teacher'). His next words may be translated as "Don't touch me, for I have not yet ascended to my Father" or "Stop clinging to me, [etc.]", the latter more probable in view of the grammar (negated present imperative: stop doing something already in progress) as well as Jesus's challenge to Thomas a week later (see John 20:24–29). Jesus then sent her to tell the other apostles the good news of his resurrection. The Gospel of John therefore portrays Mary Magdalene as the first apostle, the apostle sent to the apostles.

Because scribes were unsatisfied with the abrupt ending of the Gospel of Mark, they wrote several different alternative endings for it. In the "shorter ending", which is found in very few manuscripts, the women go to "those around Peter" and tell them what they had seen at the tomb, followed by a brief declaration of the gospel being preached from east to west. This "very forced" ending contradicts the last verse of the original gospel, stating that the women "told no one". The "longer ending", which is found in most surviving manuscripts, is an "amalgam of traditions" containing episodes derived from the other gospels. First, it describes an appearance by Jesus to Mary Magdalene alone (as in the Gospel of John), followed by brief descriptions of him appearing to the two disciples on the road to Emmaus (as in the Gospel of Luke) and to the eleven remaining disciples (as in the Gospel of Matthew).

In his book published in 2006, Ehrman states that "it appears virtually certain" that the stories of the empty tomb, regardless of whether or not they are accurate, can definitely be traced back to the historical Mary Magdalene, saying that, in Jewish society, women were regarded as unreliable witnesses and were forbidden from giving testimony in court, so early Christians would have had no motive to make up a story about a woman being the first to discover the empty tomb. In fact, if they had made the story up, they would have had strong motivation to make Peter, Jesus's closest disciple while he was alive, the discoverer of the tomb instead. He also says that the story of Mary Magdalene discovering the empty tomb is independently attested in the Synoptics, the Gospel of John, and in the Gospel of Peter. N. T. Wright states that, "it is, frankly, impossible to imagine that [the women at the tomb] were inserted into the tradition after Paul's day."

Casey challenges this argument, contending that the women at the tomb are not legal witnesses, but rather heroines in line with a long Jewish tradition. He contends that the story of the empty tomb was invented by either the author of the Gospel of Mark or by one of his sources, based on the historically genuine fact that the women really had been present at Jesus's crucifixion and burial. In his book published in 2014, Ehrman rejects his own previous argument, stating that the story of the empty tomb can only be a later invention because there is virtually no possibility that Jesus's body could have been placed in any kind of tomb and, if Jesus was never buried, then no one alive at the time could have said that his non-existent tomb had been found empty. He concludes that the idea that early Christians would have had "no motive" to make up the story simply "suffers from a poverty of imagination" and that they would have had all kinds of possible motives, especially since women were overrepresented in early Christian communities and women themselves would have had strong motivation to make up a story about other women being the first to find the tomb. He does conclude later, however, that Mary Magdalene must have been one of the people who had an experience in which she thought she saw the risen Jesus, citing her prominence in the gospel resurrection narratives and her absence everywhere else in the gospels as evidence.

Apocryphal early Christian writings

New Testament apocrypha writings mention Mary Magdalene. Some of these writings were cited as scripture by early Christians. However, they were never admitted to the canon of the New Testament. Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox and Protestant churches generally do not view these writings as part of the Bible. In these apocryphal texts, Mary Magdalene is portrayed as a visionary and leader of the early movement whom Jesus loved more than he loved the other disciples. These texts were written long after the death of the historical Mary Magdalene. They are not regarded by bible scholars as reliable sources of information about her life. Sanders summarizes the scholarly consensus that:

... very, very little in the apocryphal gospels could conceivably go back to the time of Jesus. They are legendary and mythological. Of all the apocryphal material, only some of the sayings in the Gospel of Thomas are worth consideration.

Nonetheless, the texts have been frequently promoted in modern works as though they were reliable. Such works often support sensationalist statements about Jesus and Mary Magdalene's relationship.

Dialogue of the Saviour

The earliest dialogue between Jesus and Mary Magdalene is probably the Dialogue of the Saviour, a badly damaged Gnostic text discovered in the Nag Hammadi library in 1945. The dialogue consists of a conversation between Jesus, Mary and two apostles – Thomas the Apostle and Matthew the Apostle. In saying 53, the Dialogue attributes to Mary three aphorisms that are attributed to Jesus in the New Testament: "The wickedness of each day [is sufficient]. Workers deserve their food. Disciples resemble their teachers." The narrator commends Mary stating, "she spoke this utterance as a woman who understood everything."

Pistis Sophia

The Pistis Sophia, possibly dating as early as the second century, is the best surviving of the Gnostic writings. It was discovered in the 18th century in a large volume containing numerous early Gnostic treatises. The document takes the form of a long dialogue in which Jesus answers his followers' questions. Of the 64 questions, 39 are presented by a woman who is referred to as Mary or Mary Magdalene. At one point, Jesus says, "Mary, thou blessed one, whom I will perfect in all mysteries of those of the height, discourse in openness, thou, whose heart is raised to the kingdom of heaven more than all thy brethren." At another point, he tells her, "Well done, Mary. You are more blessed than all women on earth, because you will be the fullness of fullness and the completion of completion." Simon Peter, annoyed at Mary's dominance of the conversation, tells Jesus, "My master, we cannot endure this woman who gets in our way and does not let any of us speak, though she talks all the time." Mary defends herself, saying, "My master, I understand in my mind that I can come forward at any time to interpret what Pistis Sophia [a female deity] has said, but I am afraid of Peter, because he threatens me and hates our gender." Jesus assures her, "Any of those filled with the spirit of light will come forward to interpret what I say: no one will be able to oppose them."

Gospel of Thomas

The Gospel of Thomas, usually dated to the late first or early second century, was among the ancient texts discovered in the Nag Hammadi library in 1945. The Gospel of Thomas consists entirely of 114 sayings attributed to Jesus. Many of these sayings are similar to ones in the canonical gospels, but others are completely unlike anything found in the New Testament. Some scholars believe that at least a few of these sayings may authentically be traced back to the historical Jesus. Two of the sayings reference a woman named "Mary", who is generally regarded as Mary Magdalene. In saying 21, Mary herself asks Jesus, "Whom are your disciples like?" Jesus responds, "They are like children who have settled in a field which is not theirs. When the owners of the field come, they will say, 'Let us have back our field.' They (will) undress in their presence in order to let them have back their field and to give it back to them." Following this, Jesus continues his explanation with a parable about the owner of a house and a thief, ending with the common rhetoric, "Whoever has ears to hear let him hear."

Mary's mention in saying 114, however, has generated considerable controversy:

Simon Peter said to them: Let Mary go forth from among us, for women are not worthy of the life. Jesus said: Behold, I shall lead her, that I may make her male, in order that she also may become a living spirit like you males. For every woman who makes herself male shall enter into the kingdom of heaven.

In the ancient world, many patriarchal cultures believed that women were inferior to men and that they were, in essence, "imperfect men" who had not fully developed. When Peter challenges Mary's authority in this saying, he does so on the widely accepted premise that she is a woman and therefore an inferior human being. When Jesus rebukes him for this, he bases his response on the same premise, stating that Mary and all faithful women like her will become men and that salvation is therefore open to all, even those who are presently women.

Gospel of Philip

The Gospel of Philip, dating from the second or third century, survives in part among the texts found in Nag Hammadi in 1945. In a manner very similar to John 19:25–26, the Gospel of Philip presents Mary Magdalene among Jesus's female entourage, adding that she was his koinônos, a Greek word variously translated in contemporary versions as 'partner, associate, comrade, companion':

There were three who always walked with the Lord: Mary, his mother, and her sister, and Magdalene, who was called his companion. His sister, his mother and his companion were each a Mary.

— Grant 1961, pp. 129–140

The Gospel of Philip uses cognates of koinônos and Coptic equivalents to refer to the literal pairing of men and women in marriage and sexual intercourse, but also metaphorically, referring to a spiritual partnership, and the reunification of the Gnostic Christian with the divine realm. The Gospel of Philip also contains another passage relating to Jesus's relationship with Mary Magdalene. The text is badly fragmented, and speculated but unreliable additions are shown in brackets:

And the companion of the [saviour was] Mary Magdalene. [Christ] loved Mary more than [all] the disciples, [and used to] kiss her [often] on the [–]. The rest of the disciples [were offended by it and expressed disapproval]. They said to him, "Why do you love her more than all of us?" The Saviour answered and said to them, "Why do I not love you like her? When a blind man and one who sees are both together in darkness, they are no different from one another. When the light comes, then he who sees will see the light, and he who is blind will remain in darkness."

— Grant 1961, pp. 129–140

For early Christians, kissing did not have a romantic connotation and it was common for Christians to kiss their fellow believers as a way of greeting. This tradition is still practiced in many Christian congregations today and is known as the "kiss of peace". Ehrman explains that, in the context of the Gospel of Philip, the kiss of peace is used as a symbol for the passage of truth from one person to another and that it is not in any way an act of "divine foreplay".

Gospel of Mary

The Gospel of Mary is the only surviving apocryphal text named after a woman. It contains information about the role of women in the early church. The text was probably written over a century after the historical Mary Magdalene's death. The text is not attributed to her and its author is anonymous. Instead, it received its title because it is about her. The main surviving text comes from a Coptic translation preserved in a fifth-century manuscript (Berolinensis Gnosticus 8052,1) discovered in Cairo in 1896. As a result of numerous intervening conflicts, the manuscript was not published until 1955. Roughly half the text of the gospel in this manuscript has been lost; the first six pages and four from the middle are missing. In addition to this Coptic translation, two brief third-century fragments of the gospel in the original Greek (P. Rylands 463 and P. Oxyrhynchus 3525) have also been discovered, which were published in 1938 and 1983 respectively.

The first part of the gospel deals with Jesus's parting words to his followers after a post-resurrection appearance. Mary first appears in the second part, in which she tells the other disciples, who are all in fright for their own lives: "Do not weep or grieve or be in doubt, for his grace will be with you all and will protect you. Rather, let us praise his greatness, for he has prepared us and made us truly human." Unlike in the Gospel of Thomas, where women can only be saved by becoming men, in the Gospel of Mary, they can be saved just as they are. Peter approaches Mary and asks her:

"Sister we know that the Saviour loved you more than the rest of woman. Tell us the words of the Saviour which you remember which you know, but we do not, nor have we heard them". Mary answered and said, "What is hidden from you I will proclaim to you". And she began to speak to them these words: "I", she said, "I saw the Lord in a vision and I said to Him, Lord I saw you today in a vision".

— de Boer 2005, p. 74

Mary then proceeds to describe the Gnostic cosmology in depth, revealing that she is the only one who has understood Jesus's true teachings. Andrew the Apostle challenges Mary, insisting, "Say what you think about what she said, but I do not believe the savior said this. These teachings are strange ideas." Peter responds, saying, "Did he really speak with a woman in private, without our knowledge? Should we all listen to her? Did he prefer her to us?" Andrew and Peter's responses are intended to demonstrate that they do not understand Jesus's teachings and that it is really only Mary who truly understands. Matthew the Apostle comes to Mary's defense, giving a sharp rebuke to Peter: "Peter, you are always angry. Now I see you arguing against this woman like an adversary. If the savior made her worthy, who are you to reject her? Surely the savior knows her well. That is why he loved her more than us."

Borborite scriptures

The Borborites, also known as the Phibionites, were an early Christian Gnostic sect during the late fourth century who had numerous scriptures involving Mary Magdalene, including The Questions of Mary, The Greater Questions of Mary, The Lesser Questions of Mary, and The Birth of Mary. None of these texts have survived to the present, but they are mentioned by the early Christian heretic-hunter Epiphanius of Salamis in his Panarion. Epiphanius says that the Greater Questions of Mary contained an episode in which, during a post-resurrection appearance, Jesus took Mary to the top of a mountain, where he pulled a woman out of his side and engaged in sexual intercourse with her. Then, upon ejaculating, Jesus drank his own semen and told Mary, "Thus we must do, that we may live." Upon hearing this, Mary instantly fainted, to which Jesus responded by helping her up and telling her, "O thou of little faith, wherefore didst thou doubt?" This story was supposedly the basis for the Borborite Eucharist ritual in which they allegedly engaged in orgies and drank semen and menstrual blood as the "body and blood of Christ" respectively. Ehrman casts doubt on the accuracy of Epiphanius's summary, commenting that "the details of Epiphanius's description sound very much like what you can find in the ancient rumor mill about secret societies in the ancient world".

Legacy

Patristic era

Most of the earliest Church Fathers do not mention Mary Magdalene, and those who do mention her usually only discuss her very briefly. In his anti-Christian polemic The True Word, written between 170 and 180, the pagan philosopher Celsus declared that Mary Magdalene was nothing more than "a hysterical female... who either dreamt in a certain state of mind and through wishful thinking had a hallucination due to some mistaken notion (an experience which has happened to thousands), or, which is more likely, wanted to impress others by telling this fantastic tale, and so by this cock-and-bull story to provide a chance for other beggars". The Church Father Origen (c. 184 – c. 253) defended Christianity against this accusation in his apologetic treatise Against Celsus, mentioning Matthew 28:1, which lists Mary Magdalene and "the other Mary" both seeing the resurrected Jesus, thus providing a second witness. Origen also preserves a statement from Celsus that some Christians in his day followed the teachings of a woman named "Mariamme", who is almost certainly Mary Magdalene. Origen merely dismisses this, remarking that Celsus "pours on us a heap of names".

A sermon attributed to Hippolytus of Rome (c. 170 – 235) refers to Mary of Bethany and her sister Martha seeking Jesus in the garden like Mary Magdalene in John 20, indicating a conflation between Mary of Bethany and Mary Magdalene. The sermon describes the conflated woman as a "second Eve" who compensates for the disobedience of the first Eve through her obedience. The sermon also explicitly identifies Mary Magdalene and the other women as "apostles". The first clear identification of Mary Magdalene as a redeemed sinner comes from Ephrem the Syrian (c. 306 – 373). Part of the reason for the identification of Mary Magdalene as a sinner may derive from the reputation of her birthplace, Magdala, which, by the late first century, was infamous for its inhabitants' alleged vice and licentiousness.

In one of his preserved sayings, Gregory of Nyssa (c. 330 – 395) identifies Mary Magdalene as "the first witness to the resurrection, that she might set straight again by her faith in the resurrection, what was turned over in her transgression". Ambrose (c. 340 – 397), by contrast, not only rejected the conflation of Mary Magdalene, Mary of Bethany, and the anointing sinner, but even proposed that the authentic Mary Magdalene was, in fact, two separate people: one woman named Mary Magdalene who discovered the empty tomb and a different Mary Magdalene who saw the risen Christ. Augustine of Hippo (354–430) entertained the possibility that Mary of Bethany and the unnamed sinner from Luke might be the same person, but did not associate Mary Magdalene with either of them. Instead, Augustine praised Mary Magdalene as "unquestionably... surpassingly more ardent in her love than these other women who had administered to the Lord".

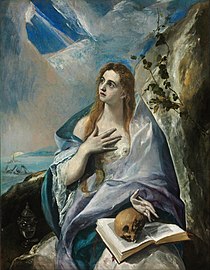

Portrayal as a prostitute

The portrayal of Mary Magdalene as a prostitute began in 591, when Pope Gregory I identified Mary Magdalene, who was introduced in Luke 8:2, with Mary of Bethany (Luke 10:39) and the unnamed "sinful woman" who anointed Jesus's feet in Luke 7:36–50. Pope Gregory's Easter sermon resulted in a widespread belief that Mary Magdalene was a repentant prostitute or promiscuous woman.

Her reputation in Western Christianity as being a repentant prostitute or loose woman are not supported by the canonical gospels, which at no point imply that she had ever been a prostitute or in any way notable for a sinful way of life. The misconception probably arose due to a conflation between Mary Magdalene, Mary of Bethany (who anoints Jesus's feet in John 11:1–12), and the unnamed "sinful woman" who anoints Jesus's feet in Luke 7:36–50. As early as the third century, the Church Father Tertullian (c. 160 – 225) references the touch of "the woman which was a sinner" in effort to prove that Jesus "was not a phantom, but really a solid body". This may indicate that Mary Magdalene was already being conflated with the "sinful woman" in Luke 7:36–50, though Tertullian never clearly identifies the woman of whom he speaks as Mary Magdalene.

Elaborate medieval legends from Western Europe then emerged, which told exaggerated tales of Mary Magdalene's wealth and beauty, as well as of her alleged journey to southern Gaul (modern-day France). The identification of Mary Magdalene with Mary of Bethany and the unnamed "sinful woman" was still a major controversy in the years leading up to the Reformation, and some Protestant leaders rejected it. During the Counter-Reformation, the Catholic Church emphasized Mary Magdalene as a symbol of penance. In 1969, Pope Paul VI removed the identification of Mary Magdalene with Mary of Bethany and the "sinful woman" from the General Roman Calendar, but the view of her as a former prostitute has persisted in popular culture.