Marriott World Trade Center

The hotel was damaged in the World Trade Center bombing by al-Qaeda terrorists on February 26, 1993. The city's Port Authority considered demolishing the building, but instead decided to repair it, reinforcing its structure. It re-opened in November 1994. In 2001, it was mostly destroyed by the collapse of the World Trade Center's Twin Towers during the September 11 attacks by al-Qaeda. 43 people inside the building died: 41 firefighters and two guests. Only the southern end of the hotel was spared, and it was eventually demolished to make way for reconstruction. The hotel was not replaced as part of the new World Trade Center complex, although its address was reused for the tower at 175 Greenwich Street.

Description

It was designed by Skidmore, Owings and Merrill in 1978–79. The building was a 22-story steel-framed structure with 825 rooms and six basement levels (labeled B1 through B6). The hotel was connected to the North Tower via an underground entrance at concourse level, and a small pedestrian walkway that extended from the west promenade of the Marriott to the North Tower on plaza level.

The hotel also had 26,000 square feet (2,400 m) of meeting space on the entire third floor. It was considered a four-diamond hotel by the American Automobile Association (AAA). It was meant for business travelers, who were offered translators and a reference library of 28 foreign-language dictionaries. The staff was also multilingual. The lobby was split between two levels, and was themed around the sea, featuring a golden sculpture of sails. On the 22nd floor, there was a gym that was the largest of any hotel in New York City at the time, with a swimming pool and a running track with views of the Hudson River and the Austin J. Tobin Plaza.

The pool was put near the top so the hotel could be flooded if a fire occurred. The hotel featured two restaurants: The Tall Ships Bar and Grill, located at street-level, and the Greenhouse Café, a restaurant on the plaza level that featured a large skylight looking up at the North and South Tower. Previously, another restaurant had operated called The American Harvest; however, it was removed following the bombing in 1993 and was renovated and remained as a rentable space called the Harvest Room.

History

The hotel was first known as the Vista International Hotel, but also became known as World Trade Center 3 (WTC 3 or 3 WTC), the World Trade Center Hotel, the Vista Hotel, and the Marriott Hotel. The building was designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill with construction beginning in March 1979. It opened on April 1, 1981, with 100 of 825 rooms available, and it was completed in July 1981. The construction cost $70 million. It was planned and managed by Hilton International, but they could not use the Hilton name for the hotel because of an agreement with Hilton Hotels to not use the name in the U.S. The Vista was the first major hotel to open in Lower Manhattan south of Canal Street since 1836. Shortly before the opening day of the hotel, a fire broke out on the 7th floor.

The Vista was first under lease to WTC Hotel Associates of Chicago. Kuo Hotel Corporation, based in Hong Kong, bought the hotel's leasehold in 1982. The hotel was successful, creating a nightlife culture in the area and spurring development of more hotels in Lower Manhattan. In 1989, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey bought the leasehold from Kuo for $78 million, but the operating rights remained in the hands of Hilton International as management agent.

1993 World Trade Center bombing

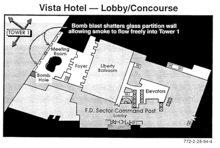

On February 26, 1993, the hotel was seriously damaged as a result of the World Trade Center bombing. Terrorists affiliated with al-Qaeda took a Ryder truck loaded with 1,500 pounds (682 kilograms) of explosives and parked it in the North Tower parking garage below the hotel's ballroom. They likely viewed this as the area where an explosion would cause the most structural damage. At 12:18 p.m. (EDT), the explosion destroyed or seriously damaged the lower- and sub-levels of the World Trade Center complex. The Marriott Financial Center, a hotel located two blocks west, served as press conference area and a command post for the law enforcement response.

The city's Port Authority considered demolishing the building for some time. The building was instead closed for 18 months while they worked on extensive repairs. Reinforcements to the hotel's structure, including the installation of "the largest steel beam ever put in a building to that point". The hotel reopened on November 1, 1994. On November 9, 1995, the hotel was sold to Host Marriott Corporation for $141.5 million. It was renamed to the New York Marriott World Trade Center. The new company managing the hotel started operations in January 1996. Security was increased at the hotel, but they were ineffective in the face of the attacks in September 2001. In January 2001, 77 New York Police Department (NYPD) police cadets graduated in a ceremony held at the hotel.

September 11 attacks

On September 11, 2001, al-Qaeda terrorists hijacked four planes to crash into various targets in the U.S. Two crashed into both of the World Trade Center's Twin Towers, which were located right next to the hotel. 43 people in the hotel died from the attacks, out of the roughly 2,753 people who died in New York City from the attacks. 41 firefighters died, along with two hotel employees who assisted them with evacuating guests. 11 guests were never identified, and it is not known if they died in the building or elsewhere in the World Trade Center complex. LDS Living claimed "most likely they were in the main towers attending business meetings or shopping." 14 people survived both collapses from inside the building.

On the 11th, the hotel had 940 registered guests. The National Association for Business Economics (NABE) was holding its yearly conference at the hotel from September 8 to 11, 2001. In addition, the hotel was planned to host the Law School Admission Council's New York City Law School Forum – a law school recruiting event – on September 14 and 15. The council was expecting 4,000 students to attend, from 160 schools. About 11 people who were planning to go to the forum were scheduled to check in to the hotel on September 11, but did not make it there before the attacks started.

Crashes into the Twin Towers

When American Airlines Flight 11 crashed into the North Tower (1 WTC) at 8:46 a.m. EDT, its landing gear fell and crashed through the roof into an office next to the 22nd-floor pool, breaking the glass above the restaurant and forcing people to duck under furniture. The whole building shook, and parts of it caught on fire. Alarms went off throughout the building, and its phones and elevators shut down. The freight elevator still worked, however. Security guards escorted out the group attending the NABE conference. The hotel's intercom told guests to be calm and stay in their rooms.

Firefighters reported human remains and corpses on the roof, from people who fell or jumped from the south face of the North Tower. At least ten firefighter companies used the lobby as a staging area; it is possible that many or all of the companies were not sent there, but instead got lost amidst the evacuation of the towers.

United Airlines Flight 175 crashed into the South Tower (2 WTC) at 9:03 a.m. Some fire companies evacuated guests that were on the upper floors, being followed by elevator mechanic Robert Graff and two employees with master keys: Joseph Keller, the hotel's executive housekeeper, and Abdul Malahi, an audiovisual technician assisting with the law school forum who was the only civilian Arab that died on 9/11. The evacuation effort was led by Keller, Richard Fetter (the hotel's resident manager), and Nancy Castillo (human resources head at Marriot World Trade Center and Marriott Financial Center). Fetter attempted to get a new version of the hotel registry, but their computer system had shut down, so he found the most recently-printed copy and a set of emergency phone numbers.

People who were escaping the tower crashes, especially the North Tower, also stopped at the hotel; these people numbered at a thousand or more. This is in part due to a door at the north face of the building, facing the North Tower. The people in the lobby moved away from the North Tower, walking south through the hotel, until they reached the Tall Ships Bar and Grill, which opened onto Liberty Street. A police officer stood at the exit, stopping civilians from crossing the street whenever debris was falling.

Collapse of the Twin Towers

The collapse of the South Tower at 9:59 a.m. crushed the middle of the building, creating a large gap that nearly split the hotel in half. The lobby was filled with debris, but nonetheless acted as a shield for firemen, police, and hotel staff, due to its reinforcements after the bombing. Abdul Malahi was killed. Before the collapse, there were seven firemen from Engine Company No. 74 in the middle of the hotel on the 21st floor, four of whom died. Around 17 people in the evacuation effort were still alive on the 3rd and 4th floors; three firefighters on these floors went upstairs to find a fireman who was radioing a mayday signal, Michael Brennan. On the half of the building that was nearer the South Tower, three civilians and two firemen trapped on the 3rd floor escaped to a reception room on the 2nd floor by crawling through an opening in a wall on an I-beam, which probably fell from the tower. In the lobby, firefighters began exiting the building to get reinforcements. Joseph Keller and Fire Lieutenant Bob Nagel were trapped by debris, and the other firefighters began trying to cut away the debris around them using saws. While this happened, the North Tower collapsed.

The collapse of the North Tower at 10:28 destroyed the rest of the hotel, aside from a small section surrounding the southern stairwell. This section would have collapsed if not for the reinforcements made after the 1993 bombing. There were 14 survivors trapped in this section, on the 2nd floor; this included 13 firemen from Company 74 and hotel guest Frank Razzano, who had evacuated from his 19th-floor room. The group found a hole in the building, and threaded either a rug or drape through it, then climbed down onto a pile of debris. Keller and the three firefighters who went to rescue Michael Brennan died from the second collapse. Six men from the Brooklyn Heights Ladder 118 fire company (including Scott Davidson, father of celebrity Pete Davidson) died from the collapse, after saving around 900 people. All the firemen still in the lobby escaped, and Richard Fetter survived.

After destruction

Bill Marriott, the businessman who owned the hotel, delivered a speech to his employees on the 20th, where he thanked them for their work on the 11th, and announced they would be employed until at least October 5, and covered by the hotel's health insurance for a year. The guests staying at the Marriott World Trade Center and the Marriott Financial Center, which was also damaged during the attacks, were sent to seven other Marriott hotels in the city. At those locations, security was increased and cancellation fees were waived.

In January 2002, the remnants of the hotel were dismantled to make way for reconstruction. The Marriott Corporation was then offered an opportunity to rebuild the hotel in the same location within the World Trade Center site, as its lease which was signed until 2094 had not expired. Marriott declined the offer, and in October 2003, the Port Authority voted on an agreement under which the Host Marriott Corporation would "surrender the premises", resulting in termination of the lease and thus giving the land to the National September 11 Memorial & Museum. Marriott thus did not have to fulfill its obligation to rebuild the hotel.

In August 2002, the FBI found what is possibly the only uninterrupted audio recording of both plane crashes into the World Trade Center, recorded by a conversation two men were having at the outdoor cafe of the hotel. One man was a city tax assessor who had allegedly been taking bribes, and the other was tax consultant Stephen McArdle, who was cooperating with an FBI investigation on the assessor by wearing a hidden wiretap which recorded their conversation to an audio tape. Both men survived, as well as the two FBI agents monitoring the wiretap.

Memorials and legacy

On the afternoon of the attacks, photographer Thomas E. Franklin captured the now-iconic image Raising the Flag at Ground Zero, depicting the U.S. flag being raised by firefighters upon a flagpole believed to have been Marriott property located on what remained of the hotel grounds. A Marriott flag that was found in the rubble in December was displayed in a glass case for the next few months, honoring the hotel's employees with the plaque: "Our Spirit to Serve From sacrifice . . . honor From adversity . . . resolve From grief . . . remembrance". The flag was eventually received by the 9/11 museum.

The Ladder 118 firetruck was recovered from Ground Zero within days of the attack, and their tools were recovered two months later. A photo of the firetruck, crossing the Brooklyn Bridge to get to the World Trade Center after the second plane crash, became an iconic image of 9/11. It was taken by Aaron McLamb from his 10th-floor workplace in Brooklyn, who brought the photo to the firehouse a week later. It was then published on the front page of the New York Daily News for October 15, 2001. Pete Davidson loosely based the 2020 film The King of Staten Island on his father's service on 9/11.

The building and its survivors were featured in the television special documentary film Hotel Ground Zero, which premiered on September 11, 2009, on the History Channel. Some survivors only found out after watching the documentary that others they had met during the attacks were still alive. The survivors have reunited near or at the hotel site multiple times. As of 2011, there was a "Marriott Hotel 9/11 memorial group" that helps survivors get in contact with each other. In 2013, there was charity run in the area to honor Ruben Correa, a firefighter who died as a part of the group on the 21st floor.

References

- ^ Dunlap, David W. (October 24, 2003). "Marriott Ceding Property Where Hotel Stood on the World Trade Center Site". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 27, 2020.

- ^ McAllister, Therese; Johnathan Barnett; John Gross; Ronald Hamburger; Jon Magnusson (May 2002). "WTC3". World Trade Center Building Performance Study. FEMA.

- ^ Hai S. Lew; Richard W. Bukowski; Nicholas J. Carino (September 2005). "Design, Construction, and Maintenance of Structural and Life Safety Systems. Federal Building and Fire Safety Investigation of the World Trade Center Disaster (NIST NCSTAR 1-1)". NIST. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST).

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 31, 2017. Retrieved June 27, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "New York Marriott World Trade Center (archived website)". Archived from the original on March 2, 2001. Retrieved March 2, 2001.

- ^ Johnston, Laurie (January 24, 1982). "VISTA HOTEL BRINGING NEW LIFE TO DOWNTOWN AREA". The New York Times. Retrieved September 10, 2024.

- ^ Lyons, Richard D. (January 22, 1989). "Success of Vista Hotel Draws Developers Downtown". The New York Times. Retrieved September 10, 2024.

- ^ Johnston, Laurie (January 24, 1982). "Vista Hotel Bringing New Life to Downtown Area". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 31, 2022.

- ^ Neal, Toby (September 11, 2021). "Orleana's one last New York swim before terror, tragedy, and disaster". www.shropshirestar.com. Retrieved July 30, 2024.

- ^ "New York Marriott World Trade Center". March 31, 2001. Archived from the original on March 31, 2001. Retrieved August 11, 2023.

- ^ "03". April 7, 2002. Archived from the original on April 7, 2002. Retrieved August 11, 2023.

- ^ Federal Emergency Management Agency, (FEMA) (2002). World Trade Center Building Performance Study: Data Collection, Preliminary Observations, and Recommendations. Government Printing Office. p. 3.1. Retrieved September 25, 2018.

- ^ "Realty News World Trade Center Getting New Tenants". The New York Times. April 1, 1979. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 27, 2020.

- ^ Gaiter, Dorothy J. (April 2, 1981). "Hotel in the Trade Center Greets Its First 100 Guests". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 27, 2020.

- ^ "The city's newest hotel, the Vista International, officially opened..." UPI. July 1, 1981. Retrieved May 23, 2018.

- ^ Eisner, Harvey (April 2002). "Terrorist Attack At New York World Trade Center". Firehouse Magazine. Archived from the original on September 27, 2009.

- ^ Dunlap, David W. (June 30, 1991). "Commercial Property: Downtown Hotels; Bond, Vista, Marriott – Now, Comes the Millenium". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 23, 2023.

- ^ Lueck, Thomas J. (May 10, 1995). "Vista Hotel for Sale, Port Authority Says". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 23, 2023.

- ^ "Port Authority Sells Hotel". The New York Times. New York City. November 10, 1995. p. 4. Retrieved January 29, 2022.

- ^ Hedgpeth, Dana (September 14, 2001). "Marriott Loses Hotels In Attack". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 19, 2019. Retrieved December 21, 2019.

- ^ Segal, David (September 10, 2006). "At a Ground Zero Hotel, Room for Miracles". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ^ Hedgpeth, Dana (September 14, 2001). "Marriott Loses Hotels In Attack". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 14, 2024.

- ^ "How This Ill-Fated Marriott Hotel and Its Brave Staff Played a Key Role in 9/11". LDS Living. September 11, 2019. Retrieved June 15, 2024.

- ^ Dwyer, Jim; Fessenden, Ford (September 11, 2002). "One Hotel's Fight to the Finish; At the Marriott, a Portal to Safety as the Towers Fell". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 15, 2024.

- ^ Martin, Douglas (December 20, 1995). "Cabbies Gain Access to Restrooms". The New York Times. New York City. p. 3. Retrieved February 19, 2022.

- ^ Baker, William. "WTC 3" (PDF). fema.gov. Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). p. 1. Retrieved December 8, 2022.

Marriott operated the hotel from 1996 until the attacks on September 11, 2001.

- ^ Graff, Garrett (September 10, 2021). "The World Trade Towers Collapsed on Will Jimeno. How Did He Survive?". Politico. Retrieved June 20, 2024.

- ^ "How the September 11 attacks unfolded | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved June 14, 2024.

- ^ Sloan, Karen (September 10, 2021). "Two decades on, 9/11 near miss still haunts law school admissions community". Reuters. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ^ Michael, Lipin. "Ground Zero - Then and Now | VOA Special Projects". projects.voanews.com. Retrieved September 10, 2024.

- ^ "How many people were killed in the September 11 attacks? | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved June 14, 2024.

- ^ Dwyer, Jim; Fessenden, Ford (September 11, 2002). "One Hotel's Fight to the Finish; At the Marriott, a Portal to Safety as the Towers Fell". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 27, 2020.

- ^ "The DC Temple on 9/11: Why the temple presidency worried it was a sitting duck". LDS Living. September 10, 2022. Retrieved July 30, 2024.

- ^ Goldstein, Daniel (September 12, 2016). "15 years after 9/11, survivors talk about how it impacted their priorities". MarketWatch. Retrieved June 27, 2020.

- ^ "Company boss watched events of 9/11 unfold around him". BBC News. September 9, 2011. Retrieved July 30, 2024.

- ^ "Opinion | 20 Years Later: My Journey as a 9/11 Survivor". The New York Times. September 10, 2021. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ^ "After Sept. 11, an Eight-Year Delayed Reunion Between Strangers". ABC News. Retrieved July 1, 2024.

- ^ "At 9/11, a journalist makes a tough life choice". NBC News. September 8, 2006. Archived from the original on June 19, 2024. Retrieved June 19, 2024.

- ^ Horswell, Cindy (March 17, 2014). "Houstonian who survived 9/11 dies". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved July 30, 2024.

- ^ Kobeisi, Kamal (September 11, 2011). "Remembering the Muslims who were killed in the 9/11 attacks". Alarabiya News. Retrieved June 14, 2024.

- ^ "9/11 Survivor Recalls Escaping Collapsing Marriott Center". Voice of America. September 10, 2013. Retrieved June 14, 2024.

- ^ "Inside the World Trade Center Marriott Hotel on September 11 | National September 11 Memorial & Museum". www.911memorial.org. Retrieved June 15, 2024.

- ^ Hood, Micaela (September 11, 2016). "'SNL' star Pete Davidson posts tribute to his father, a firefighter who died on 9/11". New York Daily News. Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ^ McKennett, Hannah (December 17, 2019). "The Story Behind The 9/11 Photo Of A Doomed Fire Truck Heading Toward The Twin Towers". All That's Interesting. Retrieved September 10, 2024.

- ^ Hood, Micaela (September 11, 2016). "'SNL' star Pete Davidson posts tribute to his father, a firefighter who died on 9/11". New York Daily News. Retrieved September 10, 2024.

- ^ "Audio Tape Reveals Sounds of Sept. 11". ABC News. Retrieved July 30, 2024.

- ^ "CNN.com – WTC attacks caught on audiotape – August 7, 2002". edition.cnn.com. Retrieved July 30, 2024.

- ^ Magazine, Smithsonian; McGreevy, Nora. "A Lesser-Known Photo of an Iconic 9/11 Moment Brings Shades of Gray to the Day's Memory". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved June 15, 2024.

- ^ "9/11 ten years later: Fear did not stop Ladder 118 crew whose bravery is captured in photo". New York Daily News. July 31, 2011. Retrieved September 10, 2024.

- ^ Margaritoff, Marco (August 2, 2024). "Meet Pete Davidson's Heroic Dad, Who Died Evacuating The World Trade Center On 9/11". All That's Interesting. Retrieved September 10, 2024.

- ^ Hotel Ground Zero. DocumentaryVine.com. September 11, 2009.

- ^ Content, Contributed (October 25, 2009). "9/11 heroes reunite with women they saved at World Trade Center hotel". New York Daily News. Retrieved June 15, 2024.

External links

- Marriott World Trade Center Survivors

- Stories by NABE members about the attack

- The 9/11 Hotel, a five-part documentary video on YouTube including interviews with surviving guests and workers at the Marriott World Trade Center

- Marriott World Trade Center Website – Archived on Internet Archive