Monumental Cemetery Of Brescia

History

The Napoleonic Edict of Saint-Cloud enacted on 12 June 1804 established some rules related to the public healthcare, imposing a certain distance between the place designated for burials and residential areas.

In 1806, Brescia was one of the first cities to promulgate a law based on the edict and the city deputation decided to establish a graveyard following the new guidelines. The designated area was chosen to be out of Porta San Giovanni, while on 12 September 1808 the City of Brescia acquired new lands for this purpose. On 19 January 1810, the bishop Gabrio Maria Nava consecrated the place and immediately after the cemetery started to be used. In 1814, after many debates about the facility enhancement, the architect Rodolfo Vantini was nominated to build a funerary chapel.

During the following years, neoclassical arcades and buildings inspired by Hellenistic architecture were added to this area thanks to Vantini even though the whole construction took several years and was only completed at the beginning of the XX century, after Vantini’s death.

Description

The main sections which compose the Cemetery are:

- The central chapel dedicated to Saint Michael, whose statue was sculpted by Democrito Gandolfi.

- The municipal chapel or Rotondina Comunale, the very first pantheon of the cemetery. From 1833 to 1904, 25 politicians and eminent personas from Brescia were buried in this chapel.

- The green hemicycle opposite to the St. Michael chapel, composed by 66 memorial cenotaphs which tribute renowned Brescian personalities: poets, entrepreneurs, intellectuals and soldiers.

- The lighthouse, which was finished in 1870, it's 60 meters high and has a circular basement surrounded by porticos and tombs, moreover, a lantern has been positioned on the top. The Berlin Victory Column by the German architect Johann Heinrich Strack was inspired by Vantini's lighthouse. Furthermore, the tomb and the statue of Rodolfo Vantini by Giovanni Seleroni have been positioned inside the monument central hall.

- The military ossuary, one of the biggest military funerary monument in Italy. It was constructed during the 1920s in order to commemorate the fallen of World War I.

- The Pantheon (or Famedio in Italian), a hall dedicated to the most eminent people from Brescia and to those who lived there.

- The pyramidal shaped tomb of Giovanni Battista Bossini.

- A section for Muslims.

Notable burials

- Tito Speri (1825–1853), patriot and hero of the Risorgimento;

- Rodolfo Vantini (1792–1856), architect and creator of the Cemetery;

- Giuseppe Zanardelli (1826–1903), jurist and politician, Prime Minister of Italy from 1901 to 1903;

- Cesare Arici (1782–1836), poet;

- Annibale Calini (1882–1916), count;

- Ugo da Como (1869–1941), politician and deputy.

- Hina Saleem (1985–2006), victim of an honour killing

Monuments

Bronze monuments

-

Christ the Redeemer

-

Zanardelli's tomb by Ettore Ximenes

-

Antonio Tagliaferri bust

-

Christ bust

-

Weeping women

-

Cuni's family tomb

-

Martinengo Cesaresco's family tomb

Marble monuments

-

Soccini's family tomb

-

Annible Calini monument

-

Facchi's family tomb

-

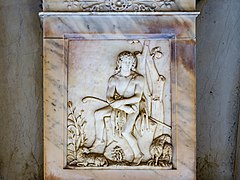

Cesare Arici monument

-

Giovan Battista Gigola monument

-

Pitozzi Baggi's family tomb

-

Panciera di Zoppola's family tomb

-

Dossi Rampinelli Spalenza's family tomb

-

Massimini's family tomb

-

Vigliani's family tomb

-

Monti della Corte's family tomb

-

Mazzucchelli's family tomb

-

Maffei Erizzo's family tomb

Gallery

-

Pietà

-

Monument to the Fallen of World War I

-

St. Michael Church

-

Tito Speri tomb

-

Don Bossini tomb

-

Eastern view

-

General view of the Cemetery

-

Tomb of Giuseppe Zanardelli

-

Prodi Bresciani monument

See also

References

- ^ Marino, Francesco (2014). Edilizia funeraria. Progettazione, normativa, esempi. Santarcangelo di Romagna: Maggioli Editore. p. 11. ISBN 9788838783425.

- ^ "vantini". 2006-05-06. Archived from the original on 2006-05-06. Retrieved 2020-12-20.

- ^ "Cimitero di Brescia o Vantiniano – Enciclopedia Bresciana". www.enciclopediabresciana.it. Retrieved 2020-12-10.

- ^ Terraroli, Valerio (2015). Il Vantiniano : guida ai monumenti. Brescia: Comune di Brescia. pp. 8–11. ISBN 979-1220006279. OCLC 1015985166.

- ^ Terraroli, Valerio (2015). Il Vantiniano : guida ai monumenti. Brescia: Comune di Brescia. p. 30. ISBN 979-1220006279. OCLC 1015985166.

- ^ Terraroli, Valerio (1990). Il Vantiniano : la scultura monumentale a Brescia tra Ottocento e Novecento. Brescia: Comune di Brescia. p. 37. ISBN 8873850669. OCLC 26126308.

- ^ Terraroli, Valerio (2015). Il Vantiniano : guida ai monumenti. Brescia: Comune di Brescia. pp. 66–67. ISBN 979-1220006279. OCLC 1015985166.

- ^ Ottaviano, Alberto. "Sono tornati a ruggire i bianchi leoni di pietra del cimitero Vantiniano" (PDF). www.ancebrescia.it.

- ^ Terraroli, Valerio (1990). Il Vantiniano : la scultura monumentale a Brescia tra Ottocento e Novecento. Brescia: Comune di Brescia. p. 72. ISBN 8873850669. OCLC 26126308.

- ^ "Savoia, Casa – Enciclopedia Bresciana". www.enciclopediabresciana.it. Retrieved 2020-12-20.

- ^ Terraroli, Valerio (2015). Il Vantiniano : guida ai monumenti. Brescia: Comune di Brescia. pp. 66–69. ISBN 979-1220006279. OCLC 1015985166.

- ^ Terraroli, Valerio (2015). Il Vantiniano : guida ai monumenti. Brescia: Comune di Brescia. pp. 66–69. ISBN 979-1220006279. OCLC 1015985166.

- ^ "Hina e quella tomba abbandonata senza volto e avvolta nell'erba". Giornale di brescia (in Italian). 2017-10-06. Retrieved 2020-12-20.

Cimitero Vantiniano, riquadro islamici [...]