Necanicum River

History

Necanicum is one of several Indian names in northwest Oregon beginning with ne, meaning place. Necanicum is derived from Ne-hay-ne-hum, the name of an Indian village once on the stream. William Clark named it Clatsop River on January 7, 1806, but the name did not stick. The river was also once known as Latty Creek, for William Latty, an early pioneer in the southern part of Seaside.

Watershed and course

The Necanicum River rises south of Humbug Mountain (not to be confused with the Humbug Mountain in southwestern Oregon), in south central Clatsop County and south of the Saddle Mountain State Natural Area. The elevation of the river's source is approximately 1,847 feet (563 m). It flows generally west, along U.S. Route 26. Approximately 3 miles (4.8 km) from the coast, east of Tillamook Head, it turns north. The river enters the Pacific Ocean at Seaside. Its final approach to the ocean is nearly parallel to the coast running south to north through the downtown of Seaside.

The watershed of the Necanicum River drains 83.7 square miles (217 km).

Heading downstream, named larger tributaries of the Necanicum River include Grindy Creek (right), Bergsvik Creek (left), Little Humbug Creek (right), North Fork Necanicum River (right), South Fork Necanicum River (left), Mail Creek (left), Klootchy Creek (right), Beeman Creek (right), Circle Creek (left), Neawanna Creek (right), and finally Neacoxie Creek (right). Neacoxie Creek flows in from the north, draining Clatsop Plains, the last tributary before the river enters the ocean.

At one time, Cullaby Lake and Cullaby Creek drained into the river via the Neacoxie. The Clatsop Canal Project – Carnahan Ditch changed this and they now drain into the Skipanon River.

Ecology and conservation

The Necanicum River watershed is important breeding, rearing, and spawning grounds for several anadromous salmonids including chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha), coho salmon (O. kisutch), chum salmon (O. keta), steelhead (O. mykiss irideus), and sea-run cutthroat trout (O. clarki clarki). Resident cutthroat trout, rainbow trout (the stream resident form of O. mykiss irideus) and Pacific lamprey (Entosphenous tridentatus) are also present in the Necanicum River.

Coho salmon use the entire Necanicum River watershed, including all of the subwatersheds but despite this extensive coho habitat, the coho population is now small. Recent intensive spawning surveys from 1990 to 2000 indicate that only about 600 fish (range 185 to 1135) now use the river. Coho salmon prefer streams with a high degree of structural complexity, including the presence of large woods, flood plains, braided channels, beaver ponds, and occasionally lakes. Anthropogenic activities, including timber harvest, mining, water withdrawals, livestock grazing, road construction, stream channelization, diking of wetlands, and urbanization have damaged this critical habitat. In the mid-1800s, three tribes of Native Americans would gather in the Necanicum estuary each fall to harvest salmon.

In 2006, the Thompson Creek-Stanley Marsh wetland restoration project of the North Coast Land Conservancy began opening ditches that border 80 acres (32 ha) of pasture so that it can be restored to a functioning Sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis) wetland. Addition of large woody debris and plantings of native willow, alder, spruce, and other wetland vegetation have attracted beaver who have built several dams, accelerating the conversion of the man-made pasture back to wetland. Coho salmon populations are already increasing on Thompson Creek, a tributary of Neawanna Creek. By using beavers to do most of the work instead of using the usual excavation and restoration techniques for wetlands mitigation, the project cost was reduced by an estimated $60,000 to $80,000.

The watershed is also important habitat for Roosevelt elk (Cervus canadensis roosevelti), black tailed deer (Odocoileus hemionus), beaver (Castor canadensis), North American river otters (Lontra canadensis), northern red-legged frog (Rana aurora), and a wide range of birds, from year-round residents like great blue herons (Ardea herodias) to migrating barn and tree swallows (Hirundo rustica and Tachycineta bicolor, respectively).

See also

Images

-

Aerial image of the river flowing south-to-north until turning west to the Pacific

-

A bridge over the river in the town of Seaside

-

Flowing through the town of Seaside

-

The river in the town of Seaside with boat rental pier

-

Seaside Convention Center with boat rental pier

-

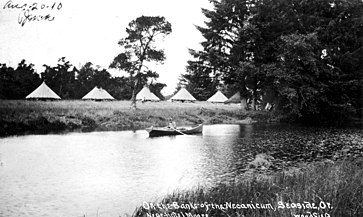

Historic photo: On the banks of the river near Hotel Moore in Seaside

References

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Necanicum River

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline data. The National Map, accessed February 21, 2013

- ^ Kai U. Snyder; Timothy J. Sullivan; Richard B. Raymond; Erin Gilbert; Deian Moore (March 2002). "Necanicum River Watershed Assessment" (PDF). E & S Environmental Chemistry, Inc. and Necanicum River Watershed Council. Retrieved 2013-02-21.

- ^ Lewis A. McArthur; Lewis L. McArthur (2003). Oregon Geographic Names. Oregon Historical Society Press. ISBN 978-0-87595-277-2.

- ^ John Ame (2007). "Necanicum Watershed". OSU Libraries. Retrieved 2013-02-21.

- ^ "North Fork Necanicum River". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior.

- ^ "South Fork Necanicum River". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior.

- ^ Mark Sytsma (2005). "Final Report Regional Lake Management Planning for TMDL Development". Portland State University. Retrieved 2016-04-21.

- ^ "Stanley Marsh Wetland Restoration". 2013-01-04. Retrieved 2013-02-21.

- ^ Nancy McCarthy (2013-02-18). "Call them the 'beaver believers'". Daily Astorian. Archived from the original on 2013-01-06. Retrieved 2013-02-21.

- ^ "Necanicum Watershed Council". Retrieved 2013-02-21.