Nowruz

The roots of Nowruz lie in Zoroastrianism, and it has been celebrated by many peoples across West Asia, Central Asia, the Caucasus and the Black Sea Basin, the Balkans, and South Asia for over 3,000 years. In the modern era, while it is observed as a secular holiday by most celebrants, Nowruz remains a holy day for Zoroastrians, Baháʼís, and Ismaʿili Shia Muslims.

For the Northern Hemisphere, Nowruz marks the beginning of spring. Customs for the festival include various fire and water rituals, celebratory dances, gift exchanges, and poetry recitations, among others; these observances differ between the cultures of the diverse communities that celebrate it.

Overview

The first day of the Iranian calendar falls on the March equinox, the first day of spring, around 21 March. In the 11th century AD the Iranian calendar was reformed by Omar Khayyam in order to fix the beginning of the calendar year, i.e. Nowruz, at the vernal equinox. Accordingly, the definition of Nowruz given by the Iranian astronomer Tusi was the following: "the first day of the official New Year [Nowruz] was always the day on which the sun entered Aries before noon." Nowruz is the first day of Farvardin, the first month of the Iranian solar calendar, which is the official calendar in use in Iran, and formerly in Afghanistan.

The United Nations officially recognized the "International Day of Nowruz" with the adoption of Resolution 64/253 by the United Nations General Assembly in February 2010.

Etymology

The word Nowruz is a combination of the Persian words نو (now, meaning 'new') and روز (ruz, 'day'). Pronunciation varies among Persian dialects, with Eastern dialects using the pronunciation [nawˈɾoːz] (as in Dari and Classical Persian, however in Tajik, it is navrūz, written наврӯз), western dialects [nowˈɾuːz], and Tehranis [noːˈɾuːz]. A variety of spelling variations for the word nowruz exist in English-language usage, including norooz, novruz, nowruz, navruz, nauruz and newroz.

Spring equinox calculation

Nowruz's timing is based on the vernal equinox. In Iran, it is the day of the new year in the Solar Hijri algorithmic calendar, which is based on precise astronomical observations, and moreover use of sophisticated intercalation system, which makes it more accurate than its European counterpart, the Gregorian calendar.

Each 2820-year great grand cycle contains 2,137 normal years of 365 days and 683 leap years of 366 days, with the average year length over the great grand cycle 365.24219852. This average is just 0.00000026 (2.6×10) of a day—slightly more than 1/50 of a second—shorter than Newcomb's value for the mean tropical year of 365.24219878 days, but differs considerably more from the current average vernal equinox year of 365.242362 days, which means that the new year, intended to fall on the vernal equinox, would drift by half a day over the course of a cycle. As the source explains, the 2820-year cycle is erroneous and has never been used in practice.

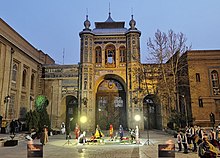

Chaharshanbe Suri

Chaharshanbe Suri (Persian: چهارشنبهسوری, romanized: čahâr-šanbeh suri (lit. "Festive Wednesday") is a prelude to the New Year. In Iran, it is celebrated on the eve of the last Wednesday before Nowruz. It is usually celebrated in the evening by performing rituals such as jumping over bonfires and lighting off firecrackers and fireworks.

In Azerbaijan, where the preparation for Novruz usually begins a month earlier, the festival is held every Tuesday during four weeks before the holiday of Novruz. Each Tuesday, people celebrate the day of one of the four elements—water, fire, earth and wind. On the holiday eve, the graves of relatives are visited and tended.

Iranians sing the poetic line "my yellow is yours, your red is mine", which means "my weakness to you and your strength to me" (Persian: سرخی تو از من، زردی من از تو, romanized: sorkhi-ye to az man, zardi-ye man az to) to the fire during the festival, asking the fire to take away ill-health and problems and replace them with warmth, health, and energy. Trail mix and berries are also served during the celebration.

Spoon banging (قاشق زنی, qāšoq zani) is a tradition observed on the eve of Charshanbe Suri, similar to the Halloween custom of trick-or-treating. In Iran, people wear disguises and go door-to-door banging spoons against plates or bowls and receive packaged snacks. In Azerbaijan, children slip around to their neighbors' homes and apartments on the last Tuesday prior to Novruz, knock at the doors, and leave their caps or little basket on the thresholds, hiding nearby to wait for candies, pastries and nuts.

The ritual of jumping over fire has continued in Armenia in the feast of Trndez, which is a feast of purification in the Armenian Apostolic Church and the Armenian Catholic Church, celebrated forty days after Jesus's birth.

Sizdah Be-dar

In Iran, the Nowruz holidays last thirteen days. On the thirteenth day of the New Year, Iranians leave their houses to enjoy nature and picnic outdoors, as part of the Sizdah Bedar ceremony. The greenery grown for the Haft-sin setting is thrown away, usually into running water. It is also customary for young single people, especially young girls, to tie the leaves of the greenery before discarding it, expressing a wish to find a partner. Another custom associated with Sizdah Bedar is the playing of jokes and pranks, similar to April Fools' Day.

History

Origin in the Iranian religions

There exist various foundation myths for Nowruz in Iranian mythology.

The Shahnameh credits the foundation of Nowruz to the mythical Iranian King Jamshid, who saves mankind from a winter destined to kill every living creature. To defeat the killer winter, Jamshid constructed a throne studded with gems. He had demons raise him above the earth into the heavens; there he sat, shining like the Sun. The world's creatures gathered and scattered jewels around him and proclaimed that this was the New Day (Now Ruz). This was the first day of Farvardin, which is the first month of the Iranian calendar.

Although it is not clear whether Proto-Indo-Iranians celebrated a feast as the first day of the calendar, there are indications that Iranians may have observed the beginning of both autumn and spring, respectively related to the harvest and the sowing of seeds, for the celebration of the New Year. Mary Boyce and Frantz Grenet explain the traditions for seasonal festivals and comment: "It is possible that the splendor of the Babylonian festivities at this season, led the Iranians to develop their own spring festival into an established New Year feast, with the name Navasarda "New Year" (a name which, though first attested through Middle Persian derivatives, is attributed to the Achaemenian period)." Akitu was the Babylonian festivity held during the spring month of Nisan in which Nowruz falls. Since the communal observations of the ancient Iranians appear in general to have been seasonal ones and related to agriculture, "it is probable that they traditionally held festivals in both autumn and spring, to mark the major turning points of the natural year."

Nowruz is partly rooted in the tradition of Iranian religions, such as Mithraism and Zoroastrianism. In Mithraism, festivals had a deep linkage with the Sun's light. The Iranian festivals such as Mehregan (autumnal equinox), Tirgan, and the eve of Chelle ye Zemestan (winter solstice) also had an origin in the Sun god (Mithra). Among other ideas, Zoroastrianism is the first monotheistic religion that emphasizes broad concepts such as the corresponding work of good and evil in the world, and the connection of humans to nature. Zoroastrian practices were dominant for much of the history of ancient Iran. In Zoroastrianism, the seven most important Zoroastrian festivals are the six Gahambar festivals and Nowruz, which occurs at the spring equinox. According to Mary Boyce, "It seems a reasonable surmise that Nowruz, the holiest of them all, with deep doctrinal significance, was founded by Zoroaster himself"; although there is no clear date of origin. Between sunset on the day of the sixth Gahambar and sunrise of Nowruz, Hamaspathmaedaya (later known, in its extended form, as Frawardinegan; and today is known as Farvardigan) was celebrated. This and the Gahambars are the only festivals named in the surviving text of the Avesta.

The 10th-century scholar Biruni, in his work Kitab al-Tafhim li Awa'il Sina'at al-Tanjim, provides a description of the calendars of various nations. Besides the Iranian calendar, various festivals of Greeks, Jews, Arabs, Sabians, and other nations are mentioned in the book. In the section on the Iranian calendar, he mentions Nowruz, Sadeh, Tirgan, Mehrgan, the six Gahambars, Farvardigan, Bahmanja, Esfand Armaz and several other festivals. According to him, "It is the belief of the Iranians that Nowruz marks the first day when the universe started its motion." The Persian historian Gardizi, in his work titled Zayn al-Akhbār, under the section of the Zoroastrians festivals, mentions Nowruz (among other festivals) and specifically points out that Zoroaster highly emphasized the celebration of Nowruz and Mehrgan.

Achaemenid period

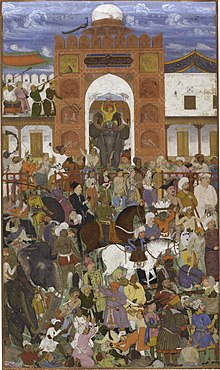

Although the word Nowruz is not recorded in Achaemenid inscriptions, there is a detailed account by Xenophon of a Nowruz celebration taking place in Persepolis and the continuity of this festival in the Achaemenid tradition. Nowruz was an important day during the Achaemenid Empire (c. 550–330 BC). Kings of the different Achaemenid nations would bring gifts to the King of Kings. The significance of the ceremony was such that King Cambyses II's appointment as the king of Babylon was legitimized only after his participation in the referred annual Achaemenid festival.

Celebrations at Persepolis

It has been suggested that the famous Persepolis complex, or at least the palace of Apadana and the Hundred Columns Hall, were built for the specific purpose of celebrating a feast related to Nowruz.

Iranian and Jewish calendars

In 539 BC, the Jews came under Iranian rule, thus exposing both groups to each other's customs. According to the Encyclopædia Britannica, the story of Purim as told in the Book of Esther is adapted from an Iranian novella about the shrewdness of harem queens, suggesting that Purim may be an adoption of Iranian New Year. A specific novella is not identified and Encyclopedia Britannica itself notes that "no Jewish texts of this genre from the Persian period are extant, so these new elements can be recognized only inferentially." Purim is celebrated the 14 of Adar, usually within a month before Nowruz (as the date of Purim is set according to the Jewish calendar, which is lunisolar), while Nowruz occurs at the spring equinox. It is possible that the Jews and Iranians of the time may have shared or adopted similar customs for these holidays. The Lunar new year of the Middle East occurs on 1 Nisan, the new moon of the first month of spring, which usually falls within a few weeks of Nowruz.

Legacy in Persian literature

In his Shahnameh, the tenth-century poet Ferdowsi narrates a fictional account of Darius III's death, where an injured Darius, with his head cradled on Alexander the Great’s thigh, asks Alexander to wed Roxana, so their children might uphold Nowruz and keep the flame of Zoroaster burning:

Her mother named her Roxana the fair; The world found joy and solace in her care. ... From her, perhaps, a glorious one shall rise; Who shall renew the name of bold Esfandiyār, wise. This sacred flame of Zoroaster, he shall adorn; The Zend and Avesta scriptures, in his hands be borne. The feast of Sadeh, this auspicious rite he'll keep; The splendor of Nowruz and fire temples deep.

— Ferdowsi

Parthian and Sasanian periods

Nowruz was the holiday of Parthian dynastic empires who ruled Iran (248 BC–224 AD) and the other areas ruled by the Arsacid dynasties outside of Parthia (such as the Arsacid dynasties of Armenia and Iberia). There are specific references to the celebration of Nowruz during the reign of Vologases I (51–78 AD), but these include no details. Before Sassanians established their power in Western Asia around 300 AD, Parthians celebrated Nowruz in autumn, and the first of Farvardin began at the autumn equinox. During the reign of the Parthian dynasty, the spring festival was Mehregan, a Zoroastrian and Iranian festival celebrated in honor of Mithra.

Extensive records on the celebration of Nowruz appear following the accession of Ardashir I, the founder of the Sasanian Empire (224–651 AD). Under the Sassanid emperors, Nowruz was celebrated as the most important day of the year. Most royal traditions of Nowruz, such as royal audiences with the public, cash gifts, and the pardoning of prisoners, were established during the Sassanid era and persisted unchanged until modern times.

Arab conquest and Islamization of Persia

Nowruz, along with the mid-winter celebration Sadeh, survived the Muslim conquest of Persia of 650 CE. Other celebrations such as the Gahambars and Mehrgan were eventually side-lined or only observed by Zoroastrians. Nowruz became the main royal holiday during the Abbasid period. Much like their predecessors in the Sasanian period, Dehqans would offer gifts to the caliphs and local rulers at the Nowruz and Mehragan festivals.

Following the demise of the caliphate and the subsequent re-emergence of Iranian dynasties such as the Samanids and Buyids, Nowruz became an even more important event. The Buyids revived the ancient traditions of Sassanian times and restored many smaller celebrations that had been eliminated by the caliphate. The Iranian Buyid ruler 'Adud al-Dawla (r. 949–983) customarily welcomed Nowruz in a majestic hall, decked with gold and silver plates and vases full of fruit and colorful flowers. The King would sit on the royal throne, and the court astronomer would come forward, kiss the ground, and congratulate him on the arrival of the New Year. The king would then summon musicians and singers, and invited his friends to gather and enjoy a great festive occasion.

Later Turkic and Mongol invaders did not attempt to abolish Nowruz.

In 1079 CE during the Seljuq dynasty era, a group of eight scholars led by astronomer and polymath Omar Khayyam calculated and established the Jalali calendar, computing the year starting from Nowruz.

The festival along with Mehregan was widely celebrated in Al-Andalus, as the Andalusians from the 9th century onwards strongly identified with many Iranian traditions despite the opposition from the Maliki jurists. Also, from the 10th century onwards the nobility, emirs and governors sponsored the celebrations and festivals. However, the jurists beginning from the 12th century started encouraging the Andalusians to celebrate Mawlid instead.

Contemporary era

Before the collapse of the Soviet Union, Iran and Afghanistan were the only countries that officially observed the ceremonies of Nowruz. When the Caucasian and Central Asian countries gained independence from the Soviets, they also declared Nowruz as a national holiday.

Nowruz was added to the UNESCO List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2010.

Customs

House cleaning and shopping

House cleaning, or shaking the house (Persian: خانه تکانی, romanized: xāne tekāni) is commonly done before the arrival of Nowruz. People start preparing for Nowruz with a major spring cleaning of their homes and by buying new clothes to wear for the New Year, as well as the purchase of flowers. The hyacinth and the tulip are popular and conspicuous.

Visiting family and friends

During the Nowruz holidays, people are expected to make short visits to the homes of family, friends and neighbors. Typically, young people will visit their elders first, and the elders return their visit later. Visitors are offered tea and pastries, cookies, fresh and dried fruits and mixed nuts or other snacks. Many Iranians throw large Nowruz parties as a way of dealing with the long distances between groups of friends and family.

Food preparation

One of the most common foods cooked on the occasion of Nowruz is Samanu (Samanak, Somank, Somalek). This food is prepared using wheat germ. In most countries that celebrate Nowruz, this food is cooked. In some countries, cooking this food is associated with certain rituals. Women and girls in different parts of Iran, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan cook Samanu in groups and sometimes during the night, and when cooking it, they sing memorable songs.

Cooking other foods is also common on Nowruz. For example, sabzi polo with fish is eaten on Eid night, as are sweets such as Nan-e Nokhodchi. In general, cooking Nowruz food is common in every region where Nowruz is celebrated, and each area has its food and sweets.

Haft-sin

Typically, before the arrival of Nowruz, family members gather around the Haft-sin table and await the exact moment of the March equinox to celebrate the New Year. The number 7 and the letter S are related to the seven Ameshasepantas as mentioned in the Zend-Avesta. They relate to the four elements of Fire, Earth, Air, Water, and the three life forms of Humans, Animals and Plants. In modern times, the explanation was simplified to mean that the Haft-sin (Persian: هفتسین, seven things beginning with the letter sin (س)) are:

- Sabze (Persian: سبزه) – wheat, barley, mung bean, or lentil sprouts grown in a dish.

- Samanu (Persian: سمنو) – sweet pudding made from wheat germ

- Persian olive (Persian: سنجد, romanized: senjed)

- Vinegar (Persian: سرکه, romanized: serke)

- Apple (Persian: سیب, romanized: sib)

- Garlic (Persian: سیر, romanized: sir)

- Sumac (Persian: سماق, romanized: somāq)

The Haft-sin table may also include a mirror, candles, painted eggs, a bowl of water, goldfish, coins, hyacinth, and traditional confectioneries. A "book of wisdom" such as the Quran, Bible, Avesta, the Šāhnāme of Ferdowsi, or the divān of Hafez may also be included. Haft-sin's origins are not clear. The practice is believed to have been popularized over the past 100 years.

Haft-mewa

In Afghanistan, people prepare Haft Mēwa (Dari: هفت میوه, English: seven fruits) for Nauruz, a mixture of seven different dried fruits and nuts (such as raisins, silver berry, pistachios, hazelnuts, prunes, walnut, and almonds) served in syrup.

Khoncha

Khoncha (Azerbaijani: Xonça) is the traditional display of Novruz in the Republic of Azerbaijan. It consists of a big silver or copper tray, with a tray of green, sprouting wheat (samani) in the middle and a dyed egg for each member of the family arranged around it. The table should be with at least seven dishes.