Oil Tanker

Oil tankers are often classified by their size as well as their occupation. The size classes range from inland or coastal tankers of a few thousand metric tons of deadweight (DWT) to ultra-large crude carriers (ULCCs) of 550,000 DWT. Tankers move approximately 2.0 billion metric tons (2.2 billion short tons) of oil every year. Second only to pipelines in terms of efficiency, the average cost of transport of crude oil by tanker amounts to only US$5 to $8 per cubic metre ($0.02 to $0.03 per US gallon).

Some specialized types of oil tankers have evolved. One of these is the naval replenishment oiler, a tanker which can fuel a moving vessel. Combination ore-bulk-oil carriers and permanently moored floating storage units are two other variations on the standard oil tanker design. Oil tankers have been involved in a number of damaging and high-profile oil spills.

History

The technology of oil transportation has evolved alongside the oil industry. Although human use of oil reaches to prehistory, the first modern commercial exploitation dates back to James Young's manufacture of paraffin in 1850. In the early 1850s, oil began to be exported from Upper Burma, then a British colony. The oil was moved in earthenware vessels to the river bank where it was then poured into boat holds for transportation to Britain.

In the 1860s, Pennsylvania oil fields became a major supplier of oil, and a center of innovation after Edwin Drake had struck oil near Titusville, Pennsylvania. Break-bulk boats and barges were originally used to transport Pennsylvania oil in 40-US-gallon (150 L) wooden barrels. But transport by barrel had several problems. The first problem was weight: they weighed 29 kilograms (64 lb), representing 20% of the total weight of a full barrel. Other problems with barrels were their expense, their tendency to leak, and the fact that they were generally used only once. The expense was significant: for example, in the early years of the Russian oil industry, barrels accounted for half the cost of petroleum production.

Early designs

In 1863, two sail-driven tankers were built on England's River Tyne. These were followed in 1873 by the first oil-tank steamer, Vaderland (Fatherland), which was built by Palmers Shipbuilding and Iron Company for Belgian owners. The vessel's use was curtailed by US and Belgian authorities citing safety concerns. By 1871, the Pennsylvania oil fields were making limited use of oil tank barges and cylindrical railroad tank-cars similar to those in use today.

Modern oil tankers

The modern oil tanker was developed in the period from 1877 to 1885. In 1876, Ludvig and Robert Nobel, brothers of Alfred Nobel, founded Branobel (short for Brothers Nobel) in Baku, Azerbaijan. It was, during the late 19th century, one of the largest oil companies in the world.

Ludvig was a pioneer in the development of early oil tankers. He first experimented with carrying oil in bulk on single-hulled barges. Turning his attention to self-propelled tankships, he faced a number of challenges. A primary concern was to keep the cargo and fumes well away from the engine room to avoid fires. Other challenges included allowing for the cargo to expand and contract due to temperature changes, and providing a method to ventilate the tanks.

The first successful oil tanker was Zoroaster, built by Sven Alexander Almqvist in Motala Verkstad, which carried its 246 metric tons (242 long tons) of kerosene cargo in two iron tanks joined by pipes. One tank was forward of the midships engine room and the other was aft. The ship also featured a set of 21 vertical watertight compartments for extra buoyancy. The ship had a length overall of 56 metres (184 ft), a beam of 8.2 metres (27 ft), and a draft of 2.7 metres (9 ft). Unlike later Nobel tankers, the Zoroaster design was built small enough to sail from Sweden to the Caspian by way of the Baltic Sea, Lake Ladoga, Lake Onega, the Rybinsk and Mariinsk Canals and the Volga River. The aft and the stern was put together and then dismantled to make room for the mid-section as the Caspian Sea was reached.

In 1883, oil tanker design took a large step forward. Working for the Nobel company, British engineer Colonel Henry F. Swan designed a set of three Nobel tankers. Instead of one or two large holds, Swan's design used several holds which spanned the width, or beam, of the ship. These holds were further subdivided into port and starboard sections by a longitudinal bulkhead. Earlier designs suffered from stability problems caused by the free surface effect, where oil sloshing from side to side could cause a ship to capsize. But this approach of dividing the ship's storage space into smaller tanks virtually eliminated free-surface problems. This approach, almost universal today, was first used by Swan in the Nobel tankers Blesk, Lumen, and Lux.

Others point to Glückauf, another design of Colonel Swan, as being the first modern oil tanker. It adopted the best practices from previous oil tanker designs to create the prototype for all subsequent vessels of the type. It was the first dedicated steam-driven ocean-going tanker in the world and was the first ship in which oil could be pumped directly into the vessel hull instead of being loaded in barrels or drums. It was also the first tanker with a horizontal bulkhead; its features included cargo valves operable from the deck, cargo main piping, a vapor line, cofferdams for added safety, and the ability to fill a ballast tank with seawater when empty of cargo. The ship was built in Britain, and was purchased by Wilhelm Anton Riedemann, an agent for the Standard Oil Company along with several of her sister ships. After Glückauf was lost in 1893 after being grounded in fog, Standard Oil purchased the sister ships.

Asian trade

The 1880s also saw the beginnings of the Asian oil trade. The idea that led to moving Russian oil to the Far East via the Suez Canal was the brainchild of two men: importer Marcus Samuel and shipowner/broker Fred Lane. Prior bids to move oil through the canal had been rejected by the Suez Canal Company as being too risky. Samuel approached the problem a different way: asking the company for the specifications of a tanker it would allow through the canal.

Armed with the canal company's specifications, Samuel ordered three tankers from William Gray & Company in northern England. Named Murex, Conch and Clam, each had a capacity of 5,010 long tons of deadweight. These three ships were the first tankers of the Tank Syndicate, forerunner of today's Royal Dutch Shell company.

With facilities prepared in Jakarta, Singapore, Bangkok, Saigon, Hong Kong, Shanghai, and Kobe, the fledgling Shell company was ready to become Standard Oil's first challenger in the Asian market. On August 24, 1892, Murex became the first tanker to pass through the Suez Canal. By the time Shell merged with Royal Dutch Petroleum in 1907, the company had 34 steam-driven oil tankers, compared to Standard Oil's four case-oil steamers and 16 sailing tankers.

The supertanker era

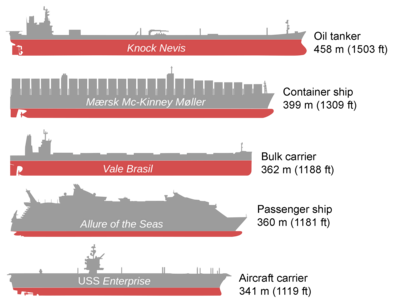

Until 1956, tankers were designed to be able to navigate the Suez Canal. This size restriction became much less of a priority after the closing of the canal during the Suez Crisis of 1956. Forced to move oil around the Cape of Good Hope, shipowners realized that bigger tankers were the key to more efficient transport. While a typical T2 tanker of the World War II era was 162 metres (532 ft) long and had a capacity of 16,500 DWT, the ultra-large crude carriers (ULCC) built in the 1970s were over 400 metres (1,300 ft) long and had a capacity of 500,000 DWT. Several factors encouraged this growth. Hostilities in the Middle East which interrupted traffic through the Suez Canal contributed, as did nationalization of Middle East oil refineries. Fierce competition among shipowners also played a part. But apart from these considerations is a simple economic advantage: the larger an oil tanker is, the more cheaply it can move crude oil, and the better it can help meet growing demands for oil.

In 1955 the world's largest supertanker was 30,708 GRT and 47,500 LT DWT: SS Spyros Niarchos launched that year by Vickers Armstrongs Shipbuilders Ltd in England for Greek shipping magnate Stavros Niarchos.

In 1958 United States shipping magnate Daniel K. Ludwig broke the record of 100,000 long tons of heavy displacement. His Universe Apollo displaced 104,500 long tons, a 23% increase from the previous record-holder, Universe Leader which also belonged to Ludwig. The first tanker over 100,000 dwt built in Europe was the British Admiral. The ship was launched at Barrow-in-Furness in 1965 by Elizabeth II.

The world's largest supertanker was built in 1979 at the Oppama shipyard by Sumitomo Heavy Industries, Ltd., named Seawise Giant. This ship was built with a capacity of 564,763 DWT, a length overall of 458.45 metres (1,504.1 ft) and a draft of 24.611 metres (80.74 ft). She had 46 tanks, 31,541 square metres (339,500 sq ft) of deck, and at her full load draft, could not navigate the English Channel.

Seawise Giant was renamed Happy Giant in 1989, Jahre Viking in 1991, and Knock Nevis in 2004 (when she was converted into a permanently moored storage tanker). In 2009 she was sold for the last time, renamed Mont, and scrapped.

As of 2011, the world's two largest working supertankers are the TI-class supertankers TI Europe and TI Oceania. These ships were built in 2002 and 2003 as Hellespont Alhambra and Hellespont Tara for the Greek Hellespont Steamship Corporation. Hellespont sold these ships to Overseas Shipholding Group and Euronav in 2004. Each of the sister ships has a capacity of over 441,500 DWT, a length overall of 380.0 metres (1,246.7 ft) and a cargo capacity of 3,166,353 barrels (503,409,900 L). They were the first ULCCs to be double-hulled. To differentiate them from smaller ULCCs, these ships are sometimes given the V-Plus size designation.

With the exception of the pipeline, the tanker is the most cost-effective way to move oil today. Worldwide, tankers carry some 2 billion barrels (3.2×10 L) annually, and the cost of transportation by tanker amounts to only US$0.02 per gallon at the pump.

Size categories

| AFRA Scale | Flexible market scale | ||||

| Class | Size in DWT | Class | Size in DWT | New price |

Used price |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Purpose tanker | 10,000–24,999 | Product tanker | 10,000–60,000 | $43M | $42.5M |

| Medium Range tanker | 25,000–44,999 | Panamax | 60,000–80,000 | ||

| LR1 (Long Range 1) | 45,000–79,999 | Aframax | 80,000–120,000 | $60.7M | $58M |

| LR2 (Long Range 2) | 80,000–159,999 | Suezmax | 120,000–200,000 | ||

| VLCC (Very Large Crude Carrier) | 160,000–319,999 | VLCC | 200,000–320,000 | $120M | $116M |

| ULCC (Ultra Large Crude Carrier) | 320,000–549,999 | ULCC | 320,000–550,000 | ||

In 1954, Shell Oil developed the "average freight rate assessment" (AFRA) system which classifies tankers of different sizes. To make it an independent instrument, Shell consulted the London Tanker Brokers' Panel (LTBP). At first, they divided the groups as General Purpose for tankers under 25,000 tons deadweight (DWT); Medium Range for ships between 25,000 and 45,000 DWT and Long Range for the then-enormous ships that were larger than 45,000 DWT. The ships became larger during the 1970s, which prompted rescaling.

The system was developed for tax reasons as the tax authorities wanted evidence that the internal billing records were correct. Before the New York Mercantile Exchange started trading crude oil futures in 1983, it was difficult to determine the exact price of oil, which could change with every contract. Shell and BP, the first companies to use the system, abandoned the AFRA system in 1983, later followed by the US oil companies. However, the system is still used today. Besides that, there is the flexible market scale, which takes typical routes and lots of 500,000 barrels (79,000 m).

Merchant oil tankers carry a wide range of hydrocarbon liquids ranging from crude oil to refined petroleum products. Crude carriers are among the largest, ranging from 55,000 DWT Panamax-sized vessels to ultra-large crude carriers (ULCCs) of over 440,000 DWT.

Smaller tankers, ranging from well under 10,000 DWT to 80,000 DWT Panamax vessels, generally carry refined petroleum products, and are known as product tankers. The smallest tankers, with capacities under 10,000 DWT generally work near-coastal and inland waterways. Although they were in the past, ships of the smaller Aframax and Suezmax classes are no longer regarded as supertankers.

VLCC and ULCC

"Supertankers" are the largest oil tankers, and the largest mobile man-made structures. They include very large and ultra-large crude carriers (VLCCs and ULCCs – see above) with capacities over 250,000 DWT. These ships can transport 2,000,000 barrels (320,000 m) of oil/318,000 metric tons. By way of comparison, the United Kingdom consumed about 1.6 million barrels (250,000 m) of oil per day in 2009. ULCCs commissioned in the 1970s were the largest vessels ever built, but have all now been scrapped. A few newer ULCCs remain in service, none of which are more than 400 meters long.

Because of their size, supertankers often cannot enter port fully loaded. These ships can take on their cargo at offshore platforms and single-point moorings. On the other end of the journey, they often pump their cargo off to smaller tankers at designated lightering points off-coast. Supertanker routes are typically long, requiring them to stay at sea for extended periods, often around seventy days at a time.

Chartering

The act of hiring a ship to carry cargo is called chartering. (The contract itself is known as a charter party.) Tankers are hired by four types of charter agreements: the voyage charter, the time charter, the bareboat charter, and contract of affreightment. In a voyage charter the charterer rents the vessel from the loading port to the discharge port. In a time charter the vessel is hired for a set period of time, to perform voyages as the charterer directs. In a bareboat charter the charterer acts as the ship's operator and manager, taking on responsibilities such as providing the crew and maintaining the vessel. Finally, in a contract of affreightment or COA, the charterer specifies a total volume of cargo to be carried in a specific time period and in specific sizes, for example a COA could be specified as 1 million barrels (160,000 m) of JP-5 in a year's time in 25,000-barrel (4,000 m) shipments.

One of the key aspects of any charter party is the freight rate, or the price specified for carriage of cargo. The freight rate of a tanker charter party is specified in one of four ways: by a lump sum rate, by rate per ton, by a time charter equivalent rate, or by Worldscale rate. In a lump sum rate arrangement, a fixed price is negotiated for the delivery of a specified cargo, and the ship's owner/operator is responsible to pay for all port costs and other voyage expenses. Rate per ton arrangements are used mostly in chemical tanker chartering, and differ from lump sum rates in that port costs and voyage expenses are generally paid by the charterer. Time charter arrangements specify a daily rate, and port costs and voyage expenses are also generally paid by the charterer.

The Worldwide Tanker Normal Freight Scale, often referred to as Worldscale, is established and governed jointly by the Worldscale Associations of London and New York. Worldscale establishes a baseline price for carrying a metric ton of product between any two ports in the world. In Worldscale negotiations, operators and charterers will determine a price based on a percentage of the Worldscale rate. The baseline rate is expressed as WS 100. If a given charter party settled on 85% of the Worldscale rate, it would be expressed as WS 85. Similarly, a charter party set at 125% of the Worldscale rate would be expressed as WS 125.

Recent markets

This section needs to be updated. (April 2020) |

| Recent time charter equivalent rates, per day | |||||||||

| Ship size |

Cargo | Route | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2010 | 2012 | 2014 | 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VLCC | Crude | Persian Gulf–Japan | $95,250 | $59,070 | $51,550 | $38,000 | $20,000 | $28,000 | $57,000 |

| Suezmax | Crude | West Africa – Caribbean or East Coast of North America |

$64,800 | $47,500 | $46,000 | $31,000 | $18,000 | $28,000 | $46,000 |

| Aframax | Crude | Cross-Mediterranean | $43,915 | $39,000 | $31,750 | $20,000 | $15,000 | $25,000 | $37,000 |

| All product carriers | Caribbean – East Coast of North America or Gulf of Mexico |

$24,550 | $25,240 | $21,400 | $11,000 | $11,000 | $12,000 | $21,000 | |

The market is affected by a wide variety of variables such as the supply and demand of oil as well as the supply and demand of oil tankers. Some particular variables include winter temperatures, excess tanker tonnage, supply fluctuations in the Persian Gulf, and interruptions in refinery services.

In 2006, time-charters tended towards long term. Of the time charters executed in that year, 58% were for a period of 24 or more months, 14% were for periods of 12 to 24 months, 4% were from 6 to 12 months, and 24% were for periods of less than 6 months.

From 2003, the demand for new ships started to grow, resulting in 2007 in a record breaking order backlog for shipyards, exceeding their capacity with rising newbuilding prices as a result. This resulted in a glut of ships when demand dropped due to a weakened global economy and dramatically reduced demand in the United States. The charter rate for very large crude carriers, which carry two million barrels of oil, had peaked at $309,601 per day in 2007 but had dropped to $7,085 per day by 2012, far below the operating costs of these ships. As a result, several tanker operators laid up their ships. Prices rose significantly in 2015 and early 2016, but delivery of new tankers was projected to keep prices in check.

Owners of large oil tanker fleets include Teekay Corporation, A P Moller Maersk, DS Torm, Frontline, MOL Tankship Management, Overseas Shipholding Group, and Euronav.

Fleet characteristics

In 2005, oil tankers made up 36.9% of the world's fleet in terms of deadweight tonnage. The world's total oil tankers deadweight tonnage has increased from 326.1 million DWT in 1970 to 960.0 million DWT in 2005. The combined deadweight tonnage of oil tankers and bulk carriers, represents 72.9% of the world's fleet.

Cargo movement

In 2005, 2.42 billion metric tons of oil were shipped by tanker. 76.7% of this was crude oil, and the rest consisted of refined petroleum products. This amounted to 34.1% of all seaborne trade for the year. Combining the amount carried with the distance it was carried, oil tankers moved 11,705 billion metric-ton-miles of oil in 2005.

By comparison, in 1970 1.44 billion metric tons of oil were shipped by tanker. This amounted to 34.1% of all seaborne trade for that year. In terms of amount carried and distance carried, oil tankers moved 6,487 billion metric-ton-miles of oil in 1970.

The United Nations also keeps statistics about oil tanker productivity, stated in terms of metric tons carried per metric ton of deadweight as well as metric-ton-miles of carriage per metric ton of deadweight. In 2005, for each 1 DWT of oil tankers, 6.7 metric tons of cargo was carried. Similarly, each 1 DWT of oil tankers was responsible for 32,400 metric-ton miles of carriage.

The main loading ports in 2005 were located in Western Asia, Western Africa, North Africa, and the Caribbean, with 196.3, 196.3, 130.2 and 246.6 million metric tons of cargo loaded in these regions. The main discharge ports were located in North America, Europe, and Japan with 537.7, 438.4, and 215.0 million metric tons of cargo discharged in these regions.

Flag states

International law requires that every merchant ship be registered in a country, called its flag state. A ship's flag state exercises regulatory control over the vessel and is required to inspect it regularly, certify the ship's equipment and crew, and issue safety and pollution prevention documents. As of 2007, the United States Central Intelligence Agency statistics count 4,295 oil tankers of 1,000 long tons deadweight (DWT) or greater worldwide. Panama was the world's largest flag state for oil tankers, with 528 of the vessels in its registry. Six other flag states had more than 200 registered oil tankers: Liberia (464), Singapore (355), China (252), Russia (250), the Marshall Islands (234) and the Bahamas (209). The Panamanian, Liberian, Marshallese and Bahamian flags are open registries and considered by the International Transport Workers' Federation to be flags of convenience. By comparison, the United States and the United Kingdom only had 59 and 27 registered oil tankers, respectively.

Vessel life cycle

In 2005, the average age of oil tankers worldwide was 10 years. Of these, 31.6% were under 4 years old and 14.3% were over 20 years old. In 2005, 475 new oil tankers were built, accounting for 30.7 million DWT. The average size for these new tankers was 64,632 DWT. Nineteen of these were VLCC size, 19 were Suezmax, 51 were Aframax, and the rest were smaller designs. By comparison, 8.0 million DWT, 8.7 million DWT, and 20.8 million DWT worth of oil tanker capacity was built in 1980, 1990, and 2000 respectively.

Ships are generally removed from the fleet through a process known as scrapping. Ship-owners and buyers negotiate scrap prices based on factors such as the ship's empty weight (called light ton displacement or LDT) and prices in the scrap metal market. In 1998, almost 700 ships went through the scrapping process at shipbreakers in places such as Gadani, Alang and Chittagong. In 2004 and 2005, 7.8 million DWT and 5.7 million DWT respectively of oil tankers were scrapped. Between 2000 and 2005, the capacity of oil tankers scrapped each year has ranged between 5.6 million DWT and 18.4 million DWT. In this same timeframe, tankers have accounted for between 56.5% and 90.5% of the world's total scrapped ship tonnage. In this period the average age of scrapped oil tankers has ranged from 26.9 to 31.5 years.

Vessel pricing

| Size | 1985 | 2005 |

|---|---|---|

| 32,000–45,000 DWT | US$18M | $43M |

| 80,000–105,000 DWT | $22M | $58M |

| 250,000–280,000 DWT | $47M | $120M |

In 2005, the price for new oil tankers in the 32,000–45,000 DWT, 80,000–105,000 DWT, and 250,000–280,000 DWT ranges were $43 million, $58 million, and $120 million respectively. In 1985 these vessels would have cost $18 million, $22 million, and $47 million respectively.

Oil tankers are often sold second hand. In 2005, 27.3 million DWT worth of oil tankers were sold used. Some representative prices for that year include $42.5 million for a 40,000 DWT tanker, $60.7 million for a 80,000–95,000 DWT, $73 million for a 130,000–150,000 DWT, and $116 million for 250,000–280,000 DWT tanker. For a concrete example, in 2006, Bonheur subsidiary First Olsen paid $76.5 million for Knock Sheen, a 159,899 DWT tanker.

The cost of operating the largest tankers, the Very Large Crude Carriers, is currently between $10,000 and $12,000 per day.

Current structural design

Oil tankers generally have from 8 to 12 tanks. Each tank is split into two or three independent compartments by fore-and-aft bulkheads. The tanks are numbered with tank one being the forwardmost. Individual compartments are referred to by the tank number and the athwartships position, such as "one port", "three starboard", or "six center".

A cofferdam is a small space left open between two bulkheads, to give protection from heat, fire, or collision. Tankers generally have cofferdams forward and aft of the cargo tanks, and sometimes between individual tanks. A pumproom houses all the pumps connected to a tanker's cargo lines. Some larger tankers have two pumprooms. A pumproom generally spans the total breadth of the ship.

Hull designs

A major component of tanker architecture is the design of the hull or outer structure. A tanker with a single outer shell between the product and the ocean is said to be "single-hulled". Most newer tankers are "double hulled", with an extra space between the hull and the storage tanks. Hybrid designs such as "double-bottom" and "double-sided" combine aspects of single and double-hull designs. All single-hulled tankers around the world will be phased out by 2026, in accordance with the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships, 1973 (MARPOL). The United Nations has decided to phase out single hull oil tankers by 2010.

In 1998, the Marine Board of the National Academy of Sciences conducted a survey of industry experts regarding the pros and cons of double-hull design. Some of the advantages of the double-hull design that were mentioned include ease of ballasting in emergency situations, reduced practice of saltwater ballasting in cargo tanks decreases corrosion, increased environmental protection, cargo discharge is quicker, more complete and easier, tank washing is more efficient, and better protection in low-impact collisions and grounding.

The same report lists the following as some drawbacks to the double-hull design, including higher build costs, greater operating expenses (e.g. higher canal and port tariffs), difficulties in ballast tank ventilation, the fact that ballast tanks need continuous monitoring and maintenance, increased transverse free surface, the greater number of surfaces to maintain, the risk of explosions in double-hull spaces if a vapor detection system not fitted, and that cleaning ballast tanks is more difficult for double hull ships.

In all, double-hull tankers are said to be safer than a single-hull in a grounding incident, especially when the shore is not very rocky. The safety benefits are less clear on larger vessels and in cases of high speed impact.

Although double-hull design is superior in low energy casualties and prevents spillage in small casualties, in high energy casualties where both hulls are breached, oil can spill through the double-hull and into the sea and spills from a double-hull tanker can be significantly higher than designs like the mid-deck tanker, the Coulombi Egg Tanker and even a pre-MARPOL tanker, as the last one has a lower oil column and reaches hydrostatic balance sooner.

Inert gas system

An oil tanker's inert gas system is one of the most important parts of its design. Fuel oil itself is very difficult to ignite, but its hydrocarbon vapors are explosive when mixed with air in certain concentrations. The purpose of the system is to create an atmosphere inside tanks in which the hydrocarbon oil vapors cannot burn.

As inert gas is introduced into a mixture of hydrocarbon vapors and air, it increases the lower flammable limit or lowest concentration at which the vapors can be ignited. At the same time it decreases the upper flammable limit or highest concentration at which the vapors can be ignited. When the total concentration of oxygen in the tank decreases to about 11%, the upper and lower flammable limits converge and the flammable range disappears.

Inert gas systems deliver air with an oxygen concentration of less than 5% by volume. As a tank is pumped out, it is filled with inert gas and kept in this safe state until the next cargo is loaded. The exception is in cases when the tank must be entered. Safely gas-freeing a tank is accomplished by purging hydrocarbon vapors with inert gas until the hydrocarbon concentration inside the tank is under about 1%. Thus, as air replaces the inert gas, the concentration cannot rise to the lower flammable limit and is safe.

Cargo operations

Operations aboard oil tankers are governed by an established body of best practices and a large body of international law. Cargo can be moved on or off of an oil tanker in several ways. One method is for the ship to moor alongside a pier, connect with cargo hoses or marine loading arms. Another method involves mooring to offshore buoys, such as a single point mooring, and making a cargo connection via underwater cargo hoses. A third method is by ship-to-ship transfer, also known as lightering. In this method, two ships come alongside in open sea and oil is transferred manifold to manifold via flexible hoses. Lightering is sometimes used where a loaded tanker is too large to enter a specific port.

Pre-transfer preparation

Prior to any transfer of cargo, the chief officer must develop a transfer plan detailing specifics of the operation such as how much cargo will be moved, which tanks will be cleaned, and how the ship's ballasting will change. The next step before a transfer is the pretransfer conference. The pretransfer conference covers issues such as what products will be moved, the order of movement, names and titles of key people, particulars of shipboard and shore equipment, critical states of the transfer, regulations in effect, emergency and spill-containment procedures, watch and shift arrangements, and shutdown procedures.

After the conference is complete, the person in charge on the ship and the person in charge of the shore installation go over a final inspection checklist. In the United States, the checklist is called a Declaration of Inspection or DOI. Outside the US, the document is called the "Ship/Shore Safety Checklist." Items on the checklist include proper signals and signs are displayed, secure mooring of the vessel, choice of language for communication, securing of all connections, that emergency equipment is in place, and that no repair work is taking place.

Loading cargo

Loading an oil tanker consists primarily of pumping cargo into the ship's tanks. As oil enters the tank, the vapors inside the tank must be somehow expelled. Depending on local regulations, the vapors can be expelled into the atmosphere or discharged back to the pumping station by way of a vapor recovery line. It is also common for the ship to move water ballast during the loading of cargo to maintain proper trim.

Loading starts slowly at a low pressure to ensure that equipment is working correctly and that connections are secure. Then a steady pressure is achieved and held until the "topping-off" phase when the tanks are nearly full. Topping off is a very dangerous time in handling oil, and the procedure is handled particularly carefully. Tank-gauging equipment is used to tell the person in charge how much space is left in the tank, and all tankers have at least two independent methods for tank-gauging. As the tanker becomes full, crew members open and close valves to direct the flow of product and maintain close communication with the pumping facility to decrease and finally stop the flow of liquid.

Unloading cargo

The process of moving oil off of a tanker is similar to loading, but has some key differences. The first step in the operation is following the same pretransfer procedures as used in loading. When the transfer begins, it is the ship's cargo pumps that are used to move the product ashore. As in loading, the transfer starts at low pressure to ensure that equipment is working correctly and that connections are secure. Then a steady pressure is achieved and held during the operation. While pumping, tank levels are carefully watched and key locations, such as the connection at the cargo manifold and the ship's pumproom are constantly monitored. Under the direction of the person in charge, crew members open and close valves to direct the flow of product and maintain close communication with the receiving facility to decrease and finally stop the flow of liquid.

Tank cleaning

Tanks must be cleaned from time to time for various reasons. One reason is to change the type of product carried inside a tank. Also, when tanks are to be inspected or maintenance must be performed within a tank, it must be not only cleaned, but made gas-free.

On most crude-oil tankers, a special crude oil washing (COW) system is part of the cleaning process. The COW system circulates part of the cargo through the fixed tank-cleaning system to remove wax and asphaltic deposits. Tanks that carry less viscous cargoes are washed with water. Fixed and portable automated tank cleaning machines, which clean tanks with high-pressure water jets, are widely used. Some systems use rotating high-pressure water jets to spray hot water on all the internal surfaces of the tank. As the spraying takes place, the liquid is pumped out of the tank.

After a tank is cleaned, provided that it is going to be prepared for entry, it will be purged. Purging is accomplished by pumping inert gas into the tank until hydrocarbons have been sufficiently expelled. Next the tank is gas freed which is usually accomplished by blowing fresh air into the space with portable air powered or water powered air blowers. "Gas freeing" brings the oxygen content of the tank up to 20.8% O2. The inert gas buffer between fuel and oxygen atmospheres ensures they are never capable of ignition. Specially trained personnel monitor the tank's atmosphere, often using hand-held gas indicators which measure the percentage of hydrocarbons present. After a tank is gas-free, it may be further hand-cleaned in a manual process known as mucking. Mucking requires protocols for entry into confined spaces, protective clothing, designated safety observers, and possibly the use of airline respirators.

Special-use oil tankers

Some sub-types of oil tankers have evolved to meet specific military and economic needs. These sub-types include naval replenishment ships, oil-bulk-ore combination carriers, floating storage and offloading units (FSOs) and floating production storage and offloading units (FPSOs).

Replenishment ships

Replenishment ships, known as oilers in the United States and fleet tankers in Commonwealth countries, are ships that can provide oil products to naval vessels while on the move. This process, called underway replenishment, extends the length of time a naval vessel can stay at sea, as well as her effective range. Prior to underway replenishment, naval vessels had to enter a port or anchor to take on fuel. In addition to fuel, replenishment ships may also deliver water, ammunition, rations, stores and personnel.

Ore-bulk-oil carriers

An ore-bulk-oil carrier, also known as combination carrier or OBO, is a ship designed to be capable of carrying wet or dry bulk cargoes. This design was intended to provide flexibility in two ways. Firstly, an OBO would be able to switch between the dry and wet bulk trades based on market conditions. Secondly, an OBO could carry oil on one leg of a voyage and return carrying dry bulk, reducing the number of unprofitable ballast voyages it would have to make.

In practice, the flexibility which the OBO design allows has gone largely unused, as these ships tend to specialize in either the liquid or dry bulk trade. Also, these ships have endemic maintenance problems. On one hand, due to a less specialized design, an OBO suffers more from wear and tear during dry cargo onload than a bulker. On the other hand, components of the liquid cargo system, from pumps to valves to piping, tend to develop problems when subjected to periods of disuse. These factors have contributed to a steady reduction in the number of OBO ships worldwide since the 1970s.

One of the more famous OBOs was MV Derbyshire of 180,000 DWT which in September 1980 became the largest British ship ever lost at sea. It sank in a Pacific typhoon while carrying a cargo of iron ore from Canada to Japan.

Floating storage units

Floating storage and offloading units (FSO) are used worldwide by the offshore oil industry to receive oil from nearby platforms and store it until it can be offloaded onto oil tankers. A similar system, the floating production storage and offloading unit (FPSO), has the ability to process the product while it is on board. These floating units reduce oil production costs and offer mobility, large storage capacity, and production versatility.

FPSO and FSOs are often created out of old, stripped-down oil tankers, but can be made from new-built hulls; Shell España first used a tanker as an FPSO in August 1977. An example of an FSO that used to be an oil tanker is the Knock Nevis. These units are usually moored to the seabed through a spread mooring system. A turret-style mooring system can be used in areas prone to severe weather. This turret system lets the unit rotate to minimize the effects of sea-swell and wind.

Pollution

Oil spills have devastating effects on the environment. Crude oil contains polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) which are very difficult to clean up, and last for years in the sediment and marine environment. Marine species constantly exposed to PAHs can exhibit developmental problems, susceptibility to disease, and abnormal reproductive cycles.

By the sheer amount of oil carried, modern oil tankers can be a threat to the environment. As discussed above, a VLCC tanker can carry 2 million barrels (320,000 m) of crude oil. This is about eight times the amount spilled in the widely known Exxon Valdez incident. In this spill, the ship ran aground and dumped 10,800,000 US gallons (41,000 m) of oil into the ocean in March 1989. Despite efforts of scientists, managers, and volunteers, over 400,000 seabirds, about 1,000 sea otters, and immense numbers of fish were killed. Considering the volume of oil carried by sea, however, tanker owners' organizations often argue that the industry's safety record is excellent, with only a tiny fraction of a percentage of oil cargoes carried ever being spilled. The International Association of Independent Tanker Owners has observed that "accidental oil spills this decade have been at record low levels—one third of the previous decade and one tenth of the 1970s—at a time when oil transported has more than doubled since the mid 1980s."

Oil tankers are only one source of oil spills. According to the United States Coast Guard, 35.7% of the volume of oil spilled in the United States from 1991 to 2004 came from tank vessels (ships/barges), 27.6% from facilities and other non-vessels, 19.9% from non-tank vessels, 9.3% from pipelines, and 7.4% from mystery spills. Only 5% of the actual spills came from oil tankers, while 51.8% came from other kinds of vessels. The detailed statistics for 2004 show tank vessels responsible for somewhat less than 5% of the number of total spills but more than 60% of the volume. Tanker spills are much more rare and much more serious than spills from non-tank vessels.

The International Tanker Owners Pollution Federation has tracked 9,351 accidental spills that have occurred since 1974. According to this study, most spills result from routine operations such as loading cargo, discharging cargo, and taking on fuel oil. 91% of the operational oil spills are small, resulting in less than 7 metric tons per spill. On the other hand, spills resulting from accidents like collisions, groundings, hull failures, and explosions are much larger, with 84% of these involving losses of over 700 metric tons.

Following the Exxon Valdez spill, the United States passed the Oil Pollution Act of 1990 (OPA-90), which excluded single-hull tank vessels of 5,000 gross tons or more from US waters from 2010 onward, apart from those with a double bottom or double sides, which may be permitted to trade to the United States through 2015, depending on their age. Following the sinkings of Erika (1999) and Prestige (2002), the European Union passed its own stringent anti-pollution packages (known as Erika I, II, and III), which also require all tankers entering its waters to be double-hulled by 2010. The Erika packages are controversial because they introduced the new legal concept of "serious negligence".

-

Exxon Valdez spilled 10.8 million US gallons (41,000 m) of oil into Alaska's Prince William Sound.

-

Demonstration in Canada against oil tankers, 1970.

Air pollution

Large ships are often run on low quality fuel oils, such as bunker oil, which is highly polluting and has been shown to be a health risk.

See also

- Escambia-class replenishment oiler

- Hydraulic tanker

- List of oil spills

- List of replenishment ships of the Royal Fleet Auxiliary

- List of tankers

- List of Type T2 tankers

- Marine transfer operations

- Merchant vessel

- Petroleum transport

- Slosh dynamics

- T1 tanker

- T2 tanker

- T3 Tanker

- Type C1 ship

- Type C2 ship

- Type C3 ship

- United States Navy oiler

References

Notes

- ^ Office of Data and Economic Analysis, 2006:6.

- ^ "Tankers Listing Dec. 2010". Archived from the original on 2012-03-18. Retrieved 2011-07-16.

- ^ Hayler and Keever, 2003:14-2.

- ^ UNCTAD 2006, p. 4.

- ^ Huber, 2001: 211.

- ^ Delgado, James (1988). "Falls of Clyde National Historic Landmark Study". Maritime Heritage Program. National Park Service. Retrieved 2008-02-24.

- ^ Woodman, 1975, p. 175.

- ^ Woodman, 1975, p. 176.

- ^ Chisholm, 19:320.

- ^ Tolf, 1976, p. 54.

- ^ Chisholm, 24:881.

- ^ Vassiliou, MS (2009). Historical Dictionary of the Petroleum Industry. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810862883. Retrieved 2013-02-07.

- ^ Tolf, 1976, p. 55.

- ^ Tolf, 1976, p. 58.

- ^ Huber, 2001, p. 5.

- ^ Turpin and McEven, 1980:8–24.

- ^ "Gluckauf". Scuba Diving – New Jersey & Long Island, New York. Aberdeen, New Jersey: Rich Galiano. 28 April 2009. Archived from the original on 14 June 2012. Retrieved 20 July 2012.

- ^ Spyrou 2011.

- ^ Woodman, 1975, p. 177.

- ^ Marine Log, 2008.

- ^ Huber, 2001, p. 23.

- ^ Huber, 2001, fig. 1-16.

- ^ Meare, David. "Tirgoviste and Spyros Niarchos – IMO 5337329". Ship spotting. Retrieved 30 April 2013.

- ^ Corlett 1981, p. 25.

- ^ "Dona's Daughter". Time. 1958-12-15. Archived from the original on May 31, 2008. Retrieved 2008-04-08.

- ^ "The Biggest Tankers". Time. 1957-10-14. Archived from the original on May 21, 2008. Retrieved 2008-04-08.

- ^ Bellamy, Martin (2022). "Editorial". The Mariner's Mirror. 108 (4). Society for Nautical Research: 387. doi:10.1080/00253359.2022.2117453. S2CID 253161552.

- ^ "Knock Nevis (7381154)". Miramar Ship Index. Retrieved 2016-05-17.

- ^ Singh, 1999.

- ^ "Previous owners". Miramar Ship Index. 2016..

- ^ Bockmann, Michelle Wiese; Porter, Janet (15 December 2009). "Knock Nevis heading for Indian scrapyard". Lloyd's List. Archived from the original on January 22, 2010. Retrieved 2010-01-08.

- ^ "Overseas Shipholding Group Enters FSO Market". Press Releases. Overseas Shipholding Group. 2008-02-28. Archived from the original on 2016-01-23. Retrieved 2008-04-08.

- ^ "World's Largest Double-Hull Tanker Newbuildings Fly Marshall Islands Flag" (press release). International Registries. 2007-04-30. Archived from the original on 2015-06-20. Retrieved 2008-04-08.

- ^ "Hellespont Alhambra". Wärtsilä. 2008. Archived from the original on February 22, 2008. Retrieved 2008-04-08.

- ^ "2000's Fleet Renewal". Group History. Hellespont Shipping Corporation. 2008. Retrieved 2008-04-08.

- ^ "Fleet List". Tankers International. March 2008. Archived from the original on 2010-09-03. Retrieved 2008-04-08.

- ^ Overseas Shipholding Group, 2008, Fleet List.

- ^ Huber, 2001, p. 211.

- ^ Evangelista, Joe, ed. (Winter 2002). "Scaling the Tanker Market" (PDF). Surveyor (4). American Bureau of Shipping: 5–11. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-09-30. Retrieved 2008-02-27.

- ^ UNCTAD 2006, p. 41. Price for new vessel $ M in 2005.

- ^ UNCTAD 2006, p. 42. Five-year-old ship in $ M in 2005.

- ^ Evangelista, Joe, ed. (Winter 2002). "Shipping Shorthand" (PDF). Surveyor (4). American Bureau of Shipping: 5–11. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-09-30. Retrieved 2008-02-27.

- ^ Hayler and Keever, 2003:14-3.

- ^ For example, Time referred to the Universe Apollo, which displaced 104,500 long tons, as a supertanker in the 1958 article "Dona's Daughter". Time. 1958-12-15. Archived from the original on May 31, 2008. Retrieved 2008-04-08.

- ^ Rogers, Simon (2010-06-09). "BP energy statistics: the world in oil consumption, reserves and energy production". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 7 August 2012.

- ^ "How much bigger can container ships get?". BBC. 19 February 2013. Retrieved 19 February 2013.

- ^ Huber 2001, p. 213.

- ^ Huber 2001, p. 212.

- ^ Huber 2001, pp. 212–13.

- ^ Huber 2001, p. 225.

- ^ Huber 2001, pp. 227–28.

- ^ Huber 2001, p. 228.

- ^ Huber 2001, pp. 225–26.

- ^ Oil tanker freight-rate volatility increases, Rajesh Rana, Oil & Gas Journal, 2016-07-04

- ^ UNCTAD 2007, p. 61.

- ^ UNCTAD 2007, p. 62.

- ^ UNCTAD 2007, p. 63.

- ^ Bakkelund, Jørn (March 2008). "The Shipbuilding Market". The Platou Report. Platou: 9–13. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 16, 2009. Retrieved 2008-10-21.

- ^ WSJ 2013, p. B7.

- ^ Cochran, Ian (March 2008). "Tanker Operators Top 30 Tanker companies". Tanker Shipping Review (iPaper). Platou: 6–17.

- ^ UNCTAD 2006, p. 29.

- ^ UNCTAD 2006, p. 19.

- ^ UNCTAD 2006, p. 18.

- ^ UNCTAD 2006, p. 5.

- ^ UNCTAD 2006, p. 17.

- ^ UNCTAD 2006, p. 43.

- ^ UNCTAD 2006, p. 8.

- ^ ICFTU et al., 2002, p. 7.

- ^ Central Intelligence Agency, 2007.

- ^ "FOC Countries". International Transport Workers' Federation. 2005-06-06. Archived from the original on 2010-07-18. Retrieved 2010-07-02.

- ^ UNCTAD 2006, p. 20.

- ^ UNCTAD 2006, p. 23.

- ^ UNCTAD 2006, p. 24.

- ^ Bailey, Paul J. (2000). "Is there a decent way to break up ships?". Sectoral Activities Programme. International Labour Organization. Retrieved 2007-05-29.

- ^ Maritime Transport Coordination Platform (November 2006). "3: The London Tonnage Convention" (PDF). Tonnage Measurement Study. MTCP Work Package 2.1, Quality and Efficiency. Bremen/Brussels. p. 3.3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-03-30. Retrieved 2007-05-29.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ UNCTAD, 2006, p. 25.

- ^ UNCTAD 2006, p. 41.

- ^ UNCTAD 2006, p. 42.

- ^ GFI Securities (2010-06-30). "Benelux and Northern European Holding Companies Weekly". London: Christopher Street Capital. p. 11. Retrieved 2011-03-04.

- ^ WSJ 2013, p. 7.

- ^ "Crude oil tanker rates below levels to cover voyage costs". SeaNews Turkey. 2011-08-16. Retrieved 2013-04-21.

- ^ Turpin and McEven, 1980:8–25.

- ^ Hayler and Keever, 2003:14–4.

- ^ "Single Hull Oil Tankers Banned Worldwide from 2005". Environmental News Service. 2003-12-05.

- ^ Marine Board, NAP, 1998, p. 259, doi:10.17226/5798, ISBN 978-0-309-06370-8.

- ^ Marine Board, 1998, p. 260.

- ^ Marine Board, 1998, p. 261.

- ^ Marine Board, 1998, p. 262.

- ^ Paik, Joem K; Lee, Tak K (December 1995), "Damage and Residual Strength of Double-Hull Tankers in Grounding" (PDF), International Journal of Offshore and Polar Engineering, 5 (4), Isope, archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-10-29.

- ^ Devanney, 2006, pp. 381–383.

- ^ Hayler and Keever, 2003:14–11.

- ^ Turpin and McEwin, 1980:16–42.

- ^ Transport Canada, 1985:4.

- ^ Transport Canada, 1985:5.

- ^ Transport Canada, 1985:9.

- ^ Hayler and Keever, 2003:14-1.

- ^ Huber, 2001, p203.

- ^ Huber, 2001, p204.

- ^ Hayler and Keever, 2003:14-6.

- ^ Hayler and Keever, 2003:14-7.

- ^ Hayler and Keever, 2003:14-8.

- ^ Turpin and McEven, 1980:8–30.

- ^ Hayler and Keever, 2003:14-9.

- ^ Hayler and Keever, 2003:14-10.

- ^ Hayler and Keever, 2003:14-12.

- ^ Hayler and Keever, 2003:14-13.

- ^ Occupational Safety & Health Administration, 2008.

- ^ Military Sealift Command (April 2008). "Underway Replenishment Oilers – T-AO". Fact Sheets. United States Navy. Archived from the original on 2013-05-16. Retrieved 2008-04-08.

- ^ Department of the Navy (1959). Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Vol. 6. Office of the Chief of Naval Operations, Naval History Division. ISBN 0-16-002030-1. Retrieved 2008-02-23.

- ^ "Afloat Support" (PDF). Navy Contribution to Australian Maritime Operations. Royal Australian Navy. 2005. pp. 113–20. ISBN 0-64229615-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-01-23. Retrieved 2013-08-01.

- ^ Tarman and Heitmann, 2008.

- ^ Huber, 2001, p. 15

- ^ Douet, 1999, Abstract.

- ^ "Company Profile". Fred. Olsen Productions. 2005. Archived from the original on 2008-10-18. Retrieved 2008-10-08.

- ^ Carter, JHT; Foolen, J (1983-04-01). "Evolutionary developments advancing the floating production, storage, and offloading concept". Journal of Petroleum Technology. 35 (4): 695–700. doi:10.2118/11808-pa. OSTI 5817513.

- ^ Panetta, LE (Chair) (2003), America's living oceans: charting a course for sea change, Pew Oceans Commission.

- ^ "Cumulative Spill Data and Graphics". United States Coast Guard. 2007. Archived from the original on 2007-06-11. Retrieved 2008-04-10. Alt URL

- ^ "Oil Tanker Spill Information Pack". London: International Tanker Owners Pollution Federation. 2008. Archived from the original on 2020-12-16. Retrieved 2008-10-08.

- ^ Double-hull tanker legislation: an assessment of the Oil pollution act of 1990. Washington, DC: National Research Council, National Academy Press. 1998. doi:10.17226/5798. ISBN 978-0-309-06370-8. Retrieved 2012-06-22.

- ^ Directive 2005/35/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 7 September 2005 on ship-source pollution and on the introduction of penalties for infringements. European Parliament. Retrieved 2008-02-22.

- ^ "Frequently asked questions about the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill". State of Alaska, Exxon Valdez Oil Spill Trustee Council. 1999. Archived from the original on 2006-09-25. Retrieved 2008-10-08.

- ^ Burton, Adrian (Nov 2008), "Air Pollution: Ship Sulfate an Unexpected Heavyweight", Environmental Health Perspectives, Environ Health Prospect, 116 (11): A475, doi:10.1289/ehp.116-a475a, PMC 2592288, A475.

Bibliography

- CIA World Factbook 2008. Skyhorse Publishing. 2007. ISBN 978-1-60239-080-5. Retrieved 2008-02-22.

- Corlett, Ewan (1981). Greenhill (series), Basil (ed.). The Revolution in Merchant Shipping 1950–1980. The Ship. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office on behalf of the National Maritime Museum. pp. 24–32. ISBN 0-11-290320-7.

- "Knock Nevis (7381154)". Miramar Ship Index. Retrieved 2016-05-17.

- Devanney, Jack (2006). The Tankship Tromedy: The Impending Disasters in Tankers (PDF). Tavernier, FL: The CTX Press. ISBN 0-9776479-0-0. Archived from the original on July 8, 2008.

- Douet, M (July 1999). "Combined Ships: An Empirical Investigation About Versatility". Maritime Policy and Management. 26 (3). Taylor & Francis: 231–48. doi:10.1080/030888399286862. Archived from the original on 2008-06-11. Retrieved 2008-04-07.

- Double Hull Tankers: High Level Panel of Experts Report. European Commission, European Maritime Safety Agency. 2005.

- Evangelista, Joe, ed. (2002). "WS50" (PDF). Surveyor (Winter 2002). Houston: American Bureau of Shipping: 10–11.

- Hayler, William B.; Keever, John M. (2003). American Merchant Seaman's Manual. Cornell Maritime Pr. ISBN 0-87033-549-9.

- Huber, Mark (2001). Tanker operations: a handbook for the person-in-charge (PIC). Cambridge, MD: Cornell Maritime Press. ISBN 0-87033-528-6.

- Hendrick, Burton Jesse (2007). The Life and Letters of Walter H. Page. Vol. II. BiblioBazaar. ISBN 978-1-4346-0691-4.

- "Market Analysis" (PDF). Institute of Shipping Economics and Logistics. 2005. p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2005-12-08. Retrieved 2008-04-26.

- International Safety Guide for Oil Tankers and Terminals (ISGOTT). New York: International Chamber of Shipping, Hyperion Books. 1996. ISBN 1-85609-081-7.

- More Troubled Waters: Fishing, Pollution, and FOCs (PDF). World Summit on Sustainable Development. Johannesburg: International Confederation of Free Trade Unions, Trade Union Advisory Committee to the OECD, International Transport Workers' Federation and Greenpeace International. 2002. Retrieved 2010-06-12.

- Double-Hull Tanker Legislation: An Assessment of the Oil Pollution Act of 1990. Marine Board Commission on Engineering and Technical Systems. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. 1998. doi:10.17226/5798. ISBN 0-309-06370-1. Retrieved 2007-04-10.

- "The Liberty Ship and the T-2 Tanker (1941)". Ships of the Century. Marine Log. 2008. Archived from the original on 2008-05-05. Retrieved 2008-04-08.

- "Process: Tank Cleaning". Shipbuilding and Ship Repair – Hazards and Solutions. Department of Labor, Occupational Safety & Health Administration (OSHA). 2008-01-30. Retrieved 2008-04-08.

- "World Merchant Fleet 2001–2005" (PDF). United States Maritime Administration, Office of Data and Economic Analysis. July 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-02-21. Retrieved 2007-03-17.

- "OSG Fleet List". Overseas Shipholding Group. 2008-02-22. Archived from the original on 2008-12-09. Retrieved 2008-04-08.

- "OSG Enters FSO Market" (press release). Overseas Shipholding Group. 2008-02-28. Archived from the original on 2016-01-23. Retrieved 2008-04-08.

- Redwood, Boverton (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 21 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 316–322.

- Sawyer, L.A.; Mitchell, W.O. (1987). Sailing ship to supertanker: the hundred-year story of British Esso and its ships. Lavenham, Suffolk: Terence Dalton. ISBN 0-86138-055-X.

- Spyrou, Andrew G. (2011). From T-2 to Supertanker: Development of the Oil Tanker, 1940–2000. iUniverse. ISBN 978-0-595-36068-0. Retrieved 2013-02-07.

- Singh, Baljit (July 11, 1999). "The world's biggest ship". The Times of India. Tribune India. Retrieved 2008-04-07.

- Tarman, Daniel; Heitmann, Edgar (2008-04-07). "Case Study II: Derbyshire, Loss of a Bulk Carrier". Educational Case Studies. Washington, DC: Ship Structure Committee. Archived from the original on 2008-04-02. Retrieved 2008-04-07.

- Tolf, Robert W. (1976). "4: The World's First Oil Tankers". The Russian Rockefellers: The Saga of the Nobel Family and the Russian Oil Industry. Hoover Press. ISBN 0-8179-6581-5.

- Standard for Inert Gas Systems (PDF). Transport Canada. 1984.

- Turpin, Edward A; McEwen, William A (1980). Merchant Marine Officers' Handbook (4th ed.). Centreville, MD: Cornell Maritime Press. ISBN 0-87033-056-X.

- Review of Maritime Transport (PDF). New York and Geneva: United Nations Council on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-28. Retrieved 2008-04-13.

- "Oil-Tanker firms battle for survival", The Wall Street Journal, p. B7, April 15, 2013.

- Watts, Philip (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 24 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 880–970.

- Woodman, Richard (1998). The History of the Ship: The Comprehensive Story of Seafaring from the Earliest Times to the Present Day. New York: Lyons Press. ISBN 1-55821-681-2.

Further reading

- Shaw, Jim (March 2017), "Tank Ship Development and the birth of the American oil tanker", Ships Monthly: 26–31

- Stopford, Martin (1997). Maritime economics. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-15309-3.

- Sullivan, George (1978). Supertanker!: The Story of the World's Biggest Ships. New York: Dodd Mead. ISBN 0-396-07527-4.

External links

- Saudi shipper Bahri plans to increase VLCC fleet to 46

- ship-photos.de: Private homepage of categorized ship photos including tankers of all kinds

- Oil tanker by Picture

- "Floating Oil Tanks" Popular Mechanics, March 1930, pp. 370–374 article on the oil tankers between the World Wars

- Bill Willis. Supertankers

- Intertanko – the society of International Tanker Operators

- The International Maritime Organization – Tanker Safety (for double-hulls)

- Ship photos of tankers, ULCCs, VLCCs, barges

- Information on crude oil tankers and other forms of oil transport

- International Tanker Owners Pollution Federation Ltd. (ITOPF) Archived 2020-12-16 at the Wayback Machine

- Oil Tanker – Cleaning operations

- Winchester, Clarence, ed. (1937), "Development of the oil tanker", Shipping Wonders of the World, pp. 711–714 illustrated account of oil tanker development

- Tanker ships

- Tanker Market Outlook for 2020 – 2021

![Exxon Valdez spilled 10.8 million US gallons (41,000 m3) of oil into Alaska's Prince William Sound.[121]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/52/OilCleanupAfterValdezSpill.jpg/200px-OilCleanupAfterValdezSpill.jpg)