Olona

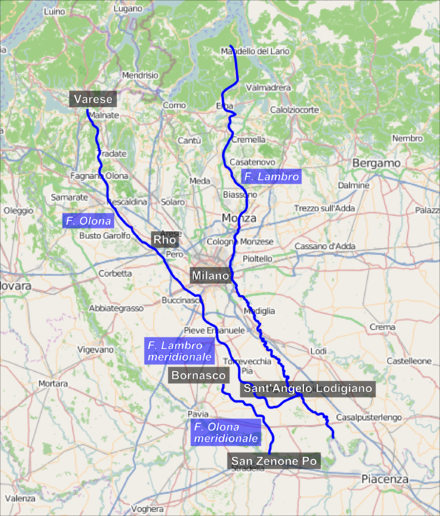

The river born at 548 meters above sea level in the Fornaci della Riana locality at the Rasa of Varese, at the Sacro Monte di Varese, within the Campo dei Fiori Regional Park. After crossing the Valle Olona and the Alto Milanese, the Olona reaches Rho where it pours part of its water into the Canale Scolmatore Nord Ovest. After passing Pero, the river enters in Milan, where, at the exit of its underground route, it flows into the Lambro Meridionale, that flows into the Lambro at Sant'Angelo Lodigiano, in the quartier of San Cristoforo ending its course. Along the way, the water system formed by the Olona and the Lambro Meridionale crosses or laps 45 towns receiving the water of 19 tributaries.

The Olona is known for the waterfalls and caves of Valganna and for having been one of the most polluted rivers in Italy. The valley carved by the river, thanks to the system of water wheels that exploited the driving force originated by the water, was one of the cradles of Italian industrialization. The Olona river consortium (it. Consorzio del fiume Olona), that is founded in 1606, is the oldest irrigation consortium in Italy.

The river is sometimes also referred to as "northern Olona" for the homonymy with another Olona, who was born in Bornasco and flows into the Po after having crossed the Province of Pavia. This second Olona, in turn, is designated as "inferior" or "southern". The homonymy is not of imitative or etymological origin, but it is due to the fact that originally it was two trunks of the same river, diverted by the ancient Romans in its upper stretch towards Milan to bring water to the moat of the defensive walls of the city.

Physical geography

The sources

The principal source of the Olona is in the Fornaci della Riana locality, at the Rasa of Varese, part of the homonymous provincial capital, at the Sacro Monte di Varese, within the Campo dei Fiori regional park. The Fornaci della Riana owe their name to some ancient limestone furnaces that remained active until 1972.

In addition to the main source, the river also flows from five other small springs, two in Val di Rasa and three in Valganna; these springs give rise to two branches joining downstream from Bregazzana (fraction of Varese).

The branch that is born to the west, in Val di Rasa, is the most important; the two springs that originate this waterway are located at the Varrò pass (between Monte Legnone and Monte Pizzella) and on Monte Chiusarella.

The main source, and the one located at the Varrò pass, join upstream from the inhabited area of the Rasa di Varese, while the spring that flows from Monte Chiusarella flows into the Olona downstream. The branch of the Valganna, which is located to the east, was born instead south of Monte Martica.

The branch of the Rasa is fed by seven small tributaries (more precisely, the torrents Legnone, Grassi, Boccaccia, Brasché, Pissabò, Valle del Forno and Sesnini), while the branch of Valganna is increased by four torrents (the Margorabbia, Valfredda, Valpissavacca and Pedana della Madonna).

The Valganna branch also gives rise to the Fonteviva lake, dedicated to sport fishing, and to the Valganna waterfalls, which in winter, due to the harsh climate, are often frozen. They are found in the municipality of Induno Olona and are close to the famous and homonymous caves. On the waterfalls, which were artificially created at the beginning of the 20th century to improve water withdrawal, one can admire the phenomenon of travertine surfacing.

The path

After the initial stretch, the river begins to travel the valley of the same name, the Valle Olona. This valley originated from the Olona and the retreat of the glaciers during the last ice age; it looks like a valley deeply engraved with the inhabited centers located on the hills overlooking the river bed, the so-called pianalti.

The slopes are mostly covered with woods, while in the valley bottom there are cultivated areas, meadows and heaths. The main tributary on Olona in the province of Varese is the Bevera; other important tributaries of this stretch of the river are the Vellone, the Gaggiolo (also called Rio Lanza, Ranza, Anza or Clivio), the Quadronna, the Selvagna, the Mornaga, the Riale delle Selve and the Tenore.

In Gorla Minore the river branches off into the Olonella, which joins the main riverbed after 1200 m. In this stretch, many artificial canals are born in the service of agriculture and of the industries that re-enter the Olona before Castellanza. After passing Castellanza, the waterway leaves the Valle Olona and heads towards the Po Valley. Once there was also another natural branch which was indicated by the name of Olonella and which crossed Legnano passing behind the basilica of San Magno. The natural island that was formed by the two branches of the river was known as "Archbishop Braida". This legnanese branch was buried in the first part of the 20th century.

After crossing San Lorenzo (fraction of Parabiago) and Nerviano, the Olona river receives its two main tributaries, the Bozzente and the Lura, at Rho. In Rho there is also the "deviator of the Olona", completed in the 1980s, which flows into Lambro Meridionale. This work has always been a source of controversy: on the one hand it has not avoided all the floods as it was designed and, on the other hand, it carries polluted water towards the Ticino. In November 2002, in particular climatic conditions, the Olona, the Seveso, the spillway and the Ticino overflowed.

From Lucernate (fraction of Rho) onwards the river no longer flows into the natural riverbed, but follows the path deviated by the ancient Romans towards the Bozzente. Entering Pero, after an initial stretch still outdoors, the Olona begins to flow under the road surface and reaches Milan by first crossing the Gallaratese, Lampugnano and QT8 districts, where it collects the water of the Merlata river (also called Fugone), to then skirt the southern slope of Monte Stella. Once in Piazza Stuparich it receives the confluence of the Pudiga (known as Mussa in his Milanese section).

Merlata and Pudiga are the water collectors that come from the area north of Milan, the so-called "groane". The Olona then runs along the Lampugnano and San Siro districts, and then continues under the avenues of the ring road bypass.

The path under the ring road, which was designed for the first time on the General Plan of Milan in 1884 (the so-called Piano Beruto), was channeled in the first two decades of the 20th century and covered in a period from 1950 to 1970. At the exit from this covered stretch, after passing under the Naviglio Grande, the Olona ends its course flowing into the Lambro Meridionale.

Until the entry into operation of the water purification system of Milan (2005), the Lambro Meridionale was a drain collector which collected the results of the western part of the city sewerage system. Subsequently, these sewage were diverted to the purifiers of San Rocco and Nosedo. From the same unloader, the Lambro Meridionale has its "clean source".

The basin

The Olona is 71 km (44 mi) long and has a drainage basin of 1,038 km (401 sq mi). The drainage basin of the Olona extends over part of the province of Varese, the Metropolitan City of Milan and, to a lesser extent, province of Como, also affecting part of Switzerland. A small part of the Gaggiolo basin, its tributary, in fact belongs to the Canton Ticino.

With its 1,038 km (401 sq mi), the Olona drainage basin occupies 5% of the Lombardy area and hosts approximately 1,000,000 inhabitants (which corresponds to around 10% of the residents in the region). The catchment area of Olona instead measures 370 km².

Any hydrographic engineers describe the Olona and the Lambro Meridionale as a single stream that flows into the Lambro at Sant'Angelo Lodigiano and which has an overall length of 121 km (75 mi).

The original bed and the two Olona

One of the most important studies on hydrography of Milan was carried out by engineer Felice Poggi. In 1911 Poggi affirmed that the two Olona, the one that flows into the Lambro Meridionale and the stream that flows into the Po at San Zenone al Po, constituted until the first years of the Common Era a single river that had a total length of 120 km (75 mi). This hypothesis has also been confirmed by subsequent studies.

The place where the river was diverted to Milan by the ancient Romans is Lucernate, a fraction of Rho. From here, to find the ancient bed of the Olona following the minimum undulations and the very small altimetric variations of the terrain, we arrive at Cascina Olona (a locality of Settimo Milanese; the toponym is indicative), in Baggio and in Corsico, with a possible variant that from Settimo Milanese would lead to Muggiano and Trezzano sul Naviglio (or Cesano Boscone).

In the neighboring towns of Cesano Boscone, Corsico and Trezzano sul Naviglio, all three of which rise on the Naviglio Grande, it is possible to identify two waterways that could flow - towards the south - into the ancient natural riverbed of the Olona to Binasco: at Trezzano sul Naviglio and Cesano Boscone would be the Belgioioso canal, while in Corsico would be the Vecchia roggia.

From Binasco, with the derivation of the Canale Ticinello, we arrive then a little further south, in the territory of Lacchiarella, where the Colombana and Carona irrigation channels bring water to the irrigation network giving rise to the Roggione. The Roggione, when at the Settimo di Bornasco receives the Olonetta canal, changes its name to lower or Olona. The Olonetta, together with the Misana canal, comes from a fountain in Misano Olona, a few kilometers upstream. Taking the old course and its name, the southern Olona flows into the Po at San Zenone al Po.

The two Olona do not have an autonomous hydrography: at Rozzano, from the Lambro Meridionale, a branch take off towards the south-west, gaining vigor thanks to the water supply provided by springs and artificial canals. This stream then flows into the southern Olona. The reconnection of the two Olona is being planned with the construction of an artificial riverbed that would resume the ancient course of the river.

The detour to Milan

Until ancient Roman times, at La Maddalena, today's quartier of Milan, the Olona was diverted towards the city with the aim of bringing water to it: in ancient Roman times it flowed into the moat of the republican defensive walls of the city of Mediolanum then, from the 12th century, in the defensive moat around the medieval walls and later (1603) in the Darsena of Porta Ticinese.

In particular Olona river, during the Middle Ages, flowed into the moat of medieval defensive walls of the city in correspondence of the modern Piazza della Resistenza Partigiana, while in ancient Roman times it continued the city route reaching the modern Piazza Vetra, where it poured its water into the moat of Roman walls thanks to the homonymous canal, the Canale Vetra. The Cerchia dei Navigli then originated from the medieval moat of walls, while the two branches of the Roman moat became the Grande Sevese and the Piccolo Sevese, two canals still existing today in the Milan underground.

The Milanese stretch of the Olona corresponds to the ancient natural beds of two streams, Bozzente and Pudiga. Before the deviation of the Olona towards Milan the Pudiga stream, after having lapped on the western side of the city, continued south following its natural bed, corresponding to what is now called Lambro Meridionale, which ended its course, like the ancient Pudiga, in the Lambro near Sant'Angelo Lodigiano. Originally, at the height of the inhabited center of Milan, the Pudiga made a wide bend towards the east, which led it to touch the city at the height of the modern Piazza Vetra, near the natural and ancient bed of the Nirone stream, and then bend towards the south following the bed of the modern Lambro Meridionale.

Originally, on its hydrographic left, the Pudiga, in place of the Olona, received the Bozzente stream. The Bozzente originally had in fact an autonomous natural bed that led him to collect the water of the Lura stream and the Merlata stream and then flow into the Pudiga. As already mentioned, it was the ancient Romans who diverted the Olona to Lucernate, a quartier of Rho, in the bed of Bozzente and then to the Pudiga riverbed. The Milanese stretch of the Olona therefore corresponds to the ancient natural beds of Bozzente and Pudiga. The new artificial riverbed of the Olona was then excavated from scratch only for a short distance: having reached the modern Lucernate at the Bozzente stream, the designers widened their bed to accommodate a greater water flow.

As the final destination of the new Olona route, the moat of Milan's Roman walls was chosen, where it poured its water into the Canale Vetra (name given by the ancient Romans to the final stretch of the Nirone natural bed) at the height of the modern and homonymous piazza: to achieve this goal, the ancient Romans extended and enlarged the Vetra canal towards the aforementioned Pudiga natural meander so as to also collect the Olona water. With the deviation of the Olona towards the wall of the city, the water continuity of the ancient bed of the Pudiga disappeared, whose southern section (the future "Lambro Meridionale") was intercepted remaining devoid of clean water, which came from the north, thus becoming in a sewer collector.

Until 1704 the river had only one terminal arm, while on a map of 1722 it is reported that the Olona forked into two almost parallel branches that met before entering Darsena of Milan: the Olona Nuova (en. "New Olona"), that is the northern one that later will be called roggia Molinara, and the Olona Vecchia (en. "Old Olona"), that it was the southern one. The Molinara canal was then buried at the end of the 19th century before the river was channeled. The so-called "Brera island", which was located between the present-day Via George Washington and Via Vincenzo Foppa, had a longer life. Originated from another fork in the river, it took its name from the homonymous farmhouse that once stood there. It is still marked in a paper from 1925. In this context, in 1894, Canottieri Olona was founded, a multi-sports club in Milan, winner of an Italian men's water polo championship, based in the Darsena of Porta Ticinese.

In 1919, as part of the complex hydrophobic revision of Milan, the channels of the current Olona route began to be built, which involved the deviation of part of the river's water towards the Lambro Meridionale passing through the outer ring road. However, the branch that led to the Darsena was maintained. The detour to the latter took place in Piazza Tripoli: here there was a lock that diverted the river by Via Roncaglia, starting what was called the "Darsena branch". In the two dry periods of the Navigli annual, the sluice was maneuvered in such a way as to completely close the Darsena branch causing the entire flow of the Olona water to flow into Lambro Meridionale. The Lambro Meridionale, which at the time was a veritable sewer collector, was also known as "Lambro Merdario" (en. "Shiter Lambro").

The new channeled route, which was also envisaged by the Beruto Plan of 1884, the first regulatory plan of Milan, did not come into operation until the early 1930s. The first covering carried out in Milan on the course of the Olona occurred in 1935 on part of the Darsena branch (from Via Valparaiso to Viale Coni Zugna), when instead of the cattle station of the railways that stood there was built the Solari Park.

The remaining part of the Darsena branch, and the canalized section along the ring road, were instead covered between 1950 and 1970. With the passing of the years, and with the increasing pollution of the river, the sluice of piazza Tripoli was not maneuvered only to divert the flow of water during the dry of the Navigli: at first it considerably reduced the flow of the Darsena branch and, at the end of the 1980s, it was resetted for "hydrogeological risk and danger of pollution" of the Darsena and the water that came out for irrigation or navigation purposes.

Origins of the name

There are three hypotheses on the origin of the toponym Olona. The first supposes that the name of the river is connected to the Celtic root Ol-, which means "large", "valid" in reference to the use of its water.

The second conjecture hypothesizes that the name derives from the ancient Greek "oros" (ὄρος), which means "relief", "mountain". The last hypothesis supposes instead that the toponym of the water course is connected to a Milanese monastery founded in the 8th century that was known as Aurona.

The latter name perhaps derives, in turn, from the name of the founder of the convent, as well as sister of the archbishop of Milan Theodorus II, "Aurona" (or "Orona"). In the latter case, the opposite has also been hypothesized, namely that the name of the monastery derives from the name of the river.

Other toponyms that were used during the history to refer to the Olona are Ollona (appeared in a document dated 737 AD), Oleunda (1033), Orona (mid-16th century) and Olonna (reported in 1688 on the Ravenna Cosmography).

Instead, as far as local toponyms are concerned, it was assumed that Lonate Pozzolo and Lonate Ceppino derive from "Olona" (from "Olona" to "Lonate").

History

Since ancient times, the inhabitants of the Valle Olona lived mainly away from the river, on higher ground that certainly would not have been hit by seasonal floods. From the archaeological findings found, it can be deduced that the Valle Olona was - already in antiquity - a significant communication route.

The water of the Olona have been used for centuries by the local population to irrigate the fields, for fishing, for the breeding of livestock, to move the wheels of water mills and, with the industrialization of its banks, to operate the hydraulic turbines serving the establishments.

From prehistory to the Middle Ages

The oldest prehistoric finds found in the areas around the natural Olona riverbed are bos primigenius bones dating back to the Würm glaciation. Unearthed in Legnano in the locality of Costa San Giorgio, they are kept in the Museo civico Guido Sutermeister.

As for the presence of man, the oldest finds discovered around the river have been found in the area of the springs. The Lake Varese was in fact frequented, between 4300 BC and 800 BC, from a palatificula civilization. According to some authors, part of these populations, following a demographic increase, migrated south settling along the Valle Olona.

Further downstream, between 1926 and 1928, near the border between Castellanza and Legnano, an artifact dating back to a period between 3400 BC and the 2200 BC came to light It is a small fragment of a bell-shaped vase that was made in the Copper Age and that can be connected to the Remedello culture. It was found during construction work on the Bustese highway 527 in the "Paradiso" quartier of Castellanza. This furniture is also kept in the Museo civico Guido Sutermeister.

Further down the valley, archaeological finds belonging to Canegrate culture have been discovered. During the excavations, 165 tombs dating from the 13th century BC were identified that are referable to the recent Bronze Age The culture of Canegrate, which has an importance that goes beyond local boundaries, developed up to the Iron Age. The chronologically later furnishings, two bronze spearheads linked to the archaic Golasecca culture and always found in Legnano, date back to between the 9th and 8th centuries BC (early Iron Age).

Along the Olona were also discovered other finds that belong to the Golasecca culture; these furnishings, which are more recent than those previously mentioned, date back to the 6th-5th century BC. The archaeological findings found along the Olona then become more and more frequent as they approach the ancient Roman conquest of the Po valley. Among them, numerous finds stand out which are connected to the La Tène culture and which were brought to light along the lower Valle Olona.

Even after the ancient Roman conquest, it took some time for the Romanization of the Valle Olona to take place; during this phase, a Celts-Roman cultural dualism coexisted. The complete Romanization of the Valle Olona occurred during the 1st century BC; after this phase, along the banks of the river, the findings of archaeological finds became more and more frequent. This abundance of furnishings continued for another two centuries, that is, until the crisis of the 3rd century AD, when a dramatic decline occurred. In Roman times, the shores of the Olona assumed significant importance due to their strategic position with respect to the communication routes between the Po valley and the Alps. In the 1st century AD, along the route drawn by the course of the river, an ancient Roman road was built, the via Severiana Augusta, which connected Mediolanum (modern Milan) with the Verbanus Lacus (Lake Maggiore), and from here to the Simplon Pass (lat. Summo Plano). The stretch of river that followed this road was channeled: there are those who hypothesize that it was this work that promoted the deviation of the Olona towards Milan.

The road built by the ancient Romans along the river kept its strategic importance even in the Middle Ages. This transit route always came from the Valle Olona connecting Milan to the northwest of Lombardy. The Olona river maintained its strategic importance for another reason over the centuries: the river was a precious source of provisioning due to the presence, along its course, of numerous water mills. The latter continued to be strategic even in the following centuries thanks to their use for agricultural purposes. In fact, the ground wheat in these mills provided food for tens of thousands of inhabitants.

In 1176 the banks of the river were theater of the decisive phases of the battle of Legnano. The Carroccio, escorted by hundreds of knights, was placed along an escarpment flanking the Olona with the aim of having a natural defense on at least one side. The decision to place the Carroccio in Legnano was not fortuitous. At the time the village of Milan represented, for those coming from the north, the gateway to the Milanese countryside: this passage had to be closed and strenuously defended to prevent the attack on Milan. For this reason, in Legnano, the Castle Visconteo was later built on a natural island of Olona river.

Already in late antiquity, along the initial stretch of the river, there was a locality, Castelseprio, which was gradually increasing its importance by extending its influence over a vast territory. Castelseprio became at first a Lombard and Frankish stronghold, and then the capital of the homonymous county due to its strategic importance. Castelseprio was in fact at the intersection of the aforementioned road that connected Milan to the Verbano and a communication route that instead headed towards Varese. In these centuries, control of the Seprio was the key to the opening of the entire Valle Olona. The Visconti, defeated the Della Torre in the battle of Desio (1287), conquered Castelseprio and imposed its destruction. The Seprio, and with it the upper part of the Valle Olona, were then definitively annexed to the Duchy of Milan in 1395.

Having become part of the Duchy of Milan and already protected for centuries by a chain of fortresses and castles, the shores of the Olona increased their development: the mills multiplied, while the contribution to irrigation remained significant. Such an intensive use of water required the Duchy of Milan to issue specific regulations (the so-called Statutes of the streets and water of the Milan countryside): this was the first time in 1346 and then in 1396.

From the Renaissance to the 17th century

The premises for the establishment of a consortium among river water users occurred in 1541, when the so-called Novae Costitutiones (in English, the "new constitutions") were signed. In this case the new contract, which had a public nature, provided for a Regius Judex Commissarius Fluminis Olona (in English, "commissioner of the river Olona"), which supervised the control of the users of the Olona water. In general, this function was covered by a representative of the Senate of Milan.

In 1548 a "shout" was issued which obliged water users to prove, by written documentation, the details of the various uses. In these centuries the distribution of water was not fair. The richest and most powerful users prevailed over the poorest and most defenseless ones.

In 1606 a real consortium, in Italian called "Consorzio del fiume Olona" (en. Olona river consortium), was formed in Milan among the users under the surveillance, also in this case, of the commissioner of the Olona river. This official, as in the past, had the task of controlling the use of the Olona water. It was no coincidence that the consortium was born in Milan: in fact the users of the water who had the most conspicuous interests dwelt in the Milanese capital.

The reasons that led to the creation of the consortium resided in an attempt to resolve the dispute between users and the Spanish government - which at the time dominated the Duchy of Milan - and in the latter's need to collect taxes from users of the Olona water in the most organized and systematic way possible. Given that the water of the Olona were always used free of charge, the historical users challenged the Government to pay the donations, while the Spaniards asserted that the taxes were due because of the status of the water, which was public.

There were two attempts to resolve the issue. The first occurred in 1610, when the government received 6,000 scudi once, while the second was in 1666, thanks to the payment of another 8,400 scudi. With this last offering, the Spaniards definitively renounced the rights on the river. That described was a private management that continued until 1921, when the water of the river were returned to the public domain. This association, which has been based in Castellanza since 1982, is the oldest irrigation consortium in Italy.

After the 17th century, craft activities along the river diversified further. In the area sawmills, tanneries, dyes, bleaches, spinning mills and weaving mills for silk, cotton and wool began to be planted. These craftsmen, to move their machinery, exploited the driving force of the river thanks to the laying of water wheels. In order to install the latter, the artisans had to ask permission from the consortium.

From 18th to 21st century

The aforementioned family-run craft activities then laid the foundations for the creation of the proto-industries. After 1820, the first proto-industrial activities started along the Olona began to exploit the motive power of the river by first purchasing, and then modifying in the most appropriate way, the water mills that for centuries were destined for the grinding of agricultural products. During the industrial development of the 19th century, many mills then became part of the proto-industrial establishments that were rising along the Olona.

The industrialization of the shores of the Olona was therefore gradual, with entrepreneurs who preferred to exploit the plumbing of the ancient mills rather than set up new ones. In other words, the industry was born as a metamorphosis of part of the ancient mills. As a consequence, the greatest concentration of proto-industrial activities occurred in correspondence of the stretches of the river where the presence of milling plants was higher.

The presence of the mills, the abundance of local labor, the existence of modern and important communication routes along the river, the presence of personalities in the area who had substantial capital to invest and the long craft tradition of the Olona Valley allowed the banks of the river to become one of the cradles of Italian industrialization.

In the mid-19th century, the primitive proto-industrial activities then turned into industries in the modern sense of the word. In this context, the shores of the Olona saw the birth of the tela Olona. This factories, which was made for the first time in the textures of Fagnano Olona, had its most common application in the sailing field. To optimize the exploitation of the current, the wheels of the mills were replaced by the most modern and efficient hydraulic turbines, the installation of which caused the abandonment and demolition of the ancient water mills, now obsolete.

With the aim of improving the flow of water and consequently increasing the efficiency of the milling plants and the efficiency of the turbines, the Olona riverbed was channeled and rectified in various sections with the elimination of natural meanders. The greatest number of rectification and canalization interventions was carried out between the 19th and 20th centuries along the stretches crossing Fagnano Olona, Legnano and Milan.

In the second half of the 19th century, steam machinery appeared, while at the beginning of the following century the exploitation of electricity began. As a result, the driving force to move the machinery no longer came from the river and therefore the hydraulic turbines were gradually abandoned. In the first post-war period the need for electric current grew, and therefore the use of the old mill wheels returned to being economically convenient, even if only for small workshops.

The ancient mills therefore resumed operating drills, planers, grinding wheels, etc., but even this new awakening soon disappeared with the changing economic conditions. The water mills that were still used in agriculture, and which had not been purchased by the companies, were then gradually made obsolete by the new industrial milling techniques.

Between 1826 and 1828, during the reconstruction work on the Spanish Porta Comasina (from 1860 called Porta Garibaldi) in neoclassical style, four colossal statues by Giambattista Perabò were added above this city gate of Milan, which symbolize allegorically the main rivers of Lombardy: Po, Adda, Ticino and Olona.

With the passage of time, the number of industries that stood along the banks of the Olona grew steadily up from 129 in 1881 to 712 in 1917. The surface of irrigated land also increased progressively: it passed from 10,801 Milanese perches in 1608, to 16,120 in 1801 and from 18,687 in 1877. In 1907, the water inlets, from the Rasa of Varese to Milan, amounted to 274. 18 of them were "free", that is, not subject to limitations, while 53 were "privileged", or subject to special regulation. All the others were subjected to a strict regulation which provided for the withdrawal of water in very precise days and times. From 1875, with the increase of the urbanization of the area, the Olona riverbed underwent, in many stretches, roofing works. These works were carried out mainly in Varese, Legnano, San Vittore Olona, Rho and Milan.

When the exploitation of the hydraulic power of the river ceased, an environmental crisis began which led the Olona to be counted among the most polluted rivers in Italy. In fact, the Olona became an easy spill for residues and sewage derived from the various productions, in particular textiles, tanning and paper-making. The first documents referring to polluting spills discharged into the Olona water date back to the mid-nineteenth century. In 1919 there were four deaths among the population, and seven among the breeding cattle, due to an anthrax infection that was caused by the poisonous water of the Olona.

The situation precipitated in the period between the two world wars. In the period of maximum pollution, which was recorded between 1950 and 1970, the water of the Olona contained highly acid substances and were soiled by residues derived from petroleum. Furthermore, they appeared colored by dyes and were characterized by the presence of a thick white foam on their surface. In 1963, the factories that discharged polluting wastes in the Olona were 88, while the population that poured its own sewage into the river amounted to about 219,000 inhabitants.

Between the 1960s and 1970s a certain sensitivity towards ecological themes was born and consolidated, which led to a position taken by civil society towards polluting spills in the Olona. Even in the 21st century, the watercourse collects civil and industrial sewage despite the fact that remediation work has already been under way since the 1980s with the construction of purifiers.

In 1998 the artisan and industrial activities present in the municipalities crossed or lapped by the Olona amounted to about 2,600 units. Almost 20,000 workers were employed in them.

The cartography

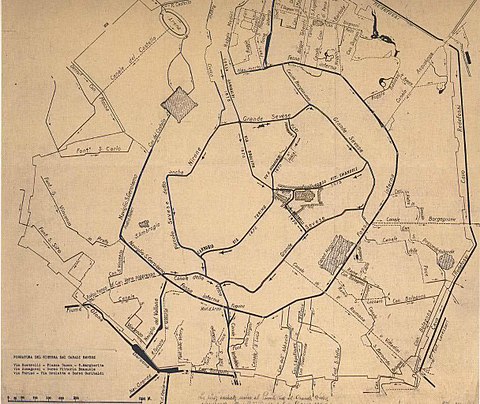

The oldest map representing the course of the Olona of which we have documented trace is dated 1608. On it are also marked the bridges and, with a good precision, the constructions along the river but not the zone of the sources and not the measures of the various properties.

For the section of Olona that crosses Milan the current route appears, as already mentioned, in the general town plan of Beruto in 1884. With it, the route of the Darsena of Milan branch is also indicated. The Darsena branch, before crossing Via Vincenzo Foppa, crossed both Via Vepra, whose name recalls both Canale Vetra, and the ancient quartier of the same name, where, after the defeat with Federico Barbarossa and the destruction of the city (1162), they were exiled the Milanese of Porta Vercellina.

Here, until the 1950s, there was the last section of a non-canalized river with a tortuous course, as well as the last artisan agglomeration that used its water for dyeing plants and laboratories for the treatment of heavy fabrics.

For the upstream section of Milan, the first map with a certain precision is a map drawn in 1763. This document illustrated the section from the sources to Gorla Minore. Later, another was drawn up in 1772 by the "conservator" of the river Giuseppe Verri and by the engineer Gaetano Raggi on behalf of the consorzio del fiume Olona. Besides the infrastructures, it also reports the canals and the locks, and therefore it is the first map endowed with a certain completeness. The richest in detail, among the oldest ones, is instead a map of 1789 which is the work of friar Mauro Fornari and Domenico Cagnoni.

Among the papers of the 19th century, are to be mentioned the map drawn by the engineer Vittore Vezzosi in 1861, which also refers to some reliefs carried out on the river, and that of the engineer Eugenio Villoresi (1878), on which the areas irrigated by the Olona are traced in great detail. The latter, in fact, also reports the canals and the irrigation ditches originating from the river.

The water

Regime of the river

The Olona regime is typically torrential due to the absence of intermediate bodies of water that regulate its flow. It has periods of high flow in March, April, October and November, and lean periods - though not dry - in July, August, December and January. The river regime is therefore characterized by a very variable flow which is a function of the seasons and of the meteorological precipitations. This variability has always caused technical difficulties in the dimensioning phase of infrastructures destined to contain floods.

The average flow of the Olona in Ponte Gurone di Malnate is 2.3 m/s (81 cu ft/s). In Rho, after the Olona receives the contributions of the Bozzente and the Lura, the average flow reaches the value of 7 m/s (250 cu ft/s) (18 m/s (640 cu ft/s) maximum). During the historic flood of 1951, a flow rate of 48.1 m/s (1,700 cu ft/s) was recorded at Castellanza, while the minimum flow rate in 1941 and 1950 reached a record value of 0.05 m/s (1.8 cu ft/s).

The average slope of the river course is 6 ‰ compared to an overall fall of 435 m (1,427 ft). The latter is calculated by subtracting the altitude of the confluence in Lambro Meridionale (113 m (371 ft) MSL) from the altitude of the main source (548 m (1,798 ft) MSL). The average width of the riverbed reaches 5 m (16 ft) at Malnate, 8 m (26 ft) at Nerviano and 18 m (59 ft) at Milan.

This scarce flow is caused by the poor water supply of springs, tributaries and meteorological precipitation. However, the limited amount of water supply did not prevent the exploitation of river water for the most varied uses. The water have been used over the centuries for the extent of the overall fall of the river, and for the flow of the river. The first, in fact, allowed the exploitation of the motive power of its water especially along the first stretch of the riverbed, which is the one with the greatest slope.

Tributaries and trough

The river has a total of 19 tributaries. The most important ones are the Lura, the Bevera, the Gaggiolo (also called "Lanza"), the Bozzente, the Vellone, the Rile, the Tenore, the Merlata, the Pudiga, the Quadronna, the Selvagna and the Fredda. We should also mention the Refreddo (also called "Fontanile Crotto"), a stream that flows in the valley floor of Castelseprio, in the area of Crotto Valle Olona, and that flows into the river just downstream.

The Olona water also comes from the springs. Many of them are famous because their water have been used for centuries for healing purposes, such as the Fontana degli Ammalati (en. "trough of the sick") of Induno Olona. Some of the troughs that feed the Olona are mentioned in various historical documents, while their first systematic census dates back to 1606. Thanks to the presence of springs, which supply water in a perennial way, the river does not run aground even in periods of drought.

In the Valle Olona there are some wetlands, including the Buzonel pond. This stretch of water, located in the valley floor between Castelseprio and Lonate Ceppino, is fed by the Bozzone stream, which later flows into the Olona.

The floods and the leans

The Olona, before the construction of embankments and canals, was a river that flogged the areas it crossed with frequent flooding. Considering the last four centuries, more than 70 floods can be counted. The first of which is known about the documents occurred in 1584 in Legnano. The last flood that caused significant damage occurred instead on 13 September 1995, while the last in chronological order took place on 29 July 2014. Among the most recent, the three floods that have done the most damage were those of 1911, 1917 and 1951. The most devastating was that of 1951, which occurred in conjunction with the Polesine flood.

The greatest number of floods occurred in the final part of the river, in the Metropolitan City of Milan. The most affected city in this section was Rho. More to the north, the most interested area was that of Clivio. The cause of these frequent overflows must be sought in the reduced extension of the river bed with respect to the flow of water that flows there. Along its banks, various works have been carried out to contain the floods. The section most interested in these works was the one that crosses the Metropolitan City of Milan.

For the upper section, the banks of the river that cross Fagnano Olona, Vedano Olona and Varese have been subjected to conspicuous interventions. A Gurone was completed in 2009 a dam with rolling tanks that regulates the flow of the river to contain floods. It is capable of forming a temporary basin of 1,570,000 m (55,000,000 cu ft) with a release of 36 m/s (1,300 cu ft/s).

Equally disastrous were the lean ones. The frequency of periods of very low water flow is comparable to that of floods. As for the historical lean, that of 1630 contributed to spreading the plague in the Alto Milanese, while that of 1734 passed to the annals for the recessive effects it had on the territory. The lean from 1747 instead went to history for its duration. To face the consequences of the lean periods, since 1346, were promulgated norms to reduce the waste and the abuses of the utilities that took water from the Olona. In these centuries, those who were caught red-handed to squander the Olona water could incur tax penalties and prison or corporal penalties. The users who suffered the most from the river's thin were the millers of the final stretch of the river.

The artificial derivations

As long as it was in operation, the stretch of the Cavo Diotti that took water from Castegnate, frazione of Castellanza, represented the most important artificial derivation of the Olona. Its northern section is still entering in the Olona, through the Bevera tributary, after having taken water from springs in the Canton of Ticino and in the territory of Viggiù. The southern section of this artificial channel, that is the one that extracted the water previously introduced in Castegnate, was instead buried in 1918 following the strong urbanization of the agricultural area of Pantanedo, frazione of Rho, which was the final user of the Cavo Diotti. Since the demand for water for irrigation purposes in Pantanedo was almost zero, this part of the canal was no longer used.

The Cavo Diotti was built in 1787. He was wanted by the lawyer Luigi Diotti, great landowner, to irrigate his properties. Diotti asked and obtained permission from Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria to carry out the work. The project was, however, a harbinger of controversy: 32 users of the river's water opposed it strenuously, claiming that the water withdrawal would be greater than its introduction. Given the government support, the consortium of the Olona river gave way and on 17 March 1786 gave permission for the start of construction work. When the Cable came into operation, the controversy did not abate. For decades there were disputes over the amount of water introduced - which many judged to be insufficient due to the measurement system - and the maintenance status of the Olona source area, where the Cavo Diotti fed water.

In 1860 two other artificial derivations were proposed. The first, which was never built due to technical difficulties and cost problems, had to extract water from Lake Lugano, while the second would have had to introduce water into the Olona thanks to a withdrawal from an artificial channel coming from the Ticino river. The two projects were approved by the Olona River Consortium on April 28, 1877. In particular, the artificial canal from Ticino, destined to flow into the Naviglio Martesana, was built from 1887 to 1890 and was called Canale Villoresi. The first entry into the Olona of water from the Canale Villoresi was completed in 1923 thanks to an outlet located in Nerviano. When fully operational, this derivation introduced into the Olona 1 m/s (35 cu ft/s). This work was intended to supply water to the downstream users of Rho, who were the ones who suffered the most from the lean periods of the river.

A fourth derivation project was proposed in 1865. This canal was supposed to draw water from Lake Varese, but it was never built for the cost, which would have been too high.

Water quality and purifiers

The water quality of the river is monitored in five monitoring stations: Varese, Lozza, Fagnano Olona, Legnano and Rho. In the first monitoring station, which is located in Varese, the river water is "acceptable" or "sufficient" and is constantly improving. In Legnano the quality of the water worsens, assuming the "poor" level, but here too an improvement is noted, since until a few years before the state of the water of the Olona was "very bad". In Rho, although slightly improving, the water of the river maintain the "very bad" degree. Downstream of the Pero purifier, the Olona water improve.

The river consortium had set itself the goal of having all the monitoring stations reach the "acceptable" level by the end of 2008, and the "good" grade by the end of 2016. From the official data, if the 2008 target was not reached, that of 2016, with the "good" grade water quality, was achieved in advance, in 2015.

These difficulties have led the Lombard regional administration to resort to extraordinary instruments such as the "river contract". This initiative provides for greater involvement of local authorities and the population concerned, with the aim of optimizing the coordination of interventions.

Along the river there are several purifiers. These wastewater treatment plants, which are managed by the Olona river consortium, were built in Varese, Olgiate Olona, Gornate Olona, Cairate, Saltrio, Cantello, Canegrate, Parabiago and Pero. For the Varese-Milan section, in 2006, there was the need to build others: of these, only that of Gornate Olona (2009) was completed.

The nature

Flora

The first part of the river runs through the Campo dei Fiori Regional Park. Up to 600 m of altitude, in this protected area, chestnuts, ash trees and linden trees prevail. Maples are common in the more humid valleys. On the summit of the Campo dei Fiori massif these plant species are replaced by beech, while birches and Scotch pines are common on the dry slopes of Monte Martica. The open spaces are embellished by now rare plants such as the Gentiana pneumonanthe and by dozens of species of wild orchids, such as, for example, the vesparia and the moscaria.

Downstream from the Campo dei Fiori, the Parco Rile Tenore Olona was established. The species that make up the flora of this protected area are mainly oaks, hornbeams, black locust, hazels, plane-trees, ash trees, oaks, poplars, elms, maples and alders. There are also many native species of shrubs, mushrooms and ferns that grow inside the Park.

The flora of the flat stretch of the Olona, which includes most of the river's path, is characterized by the massive presence of the black locust, native to North America and introduced in the Italian woods, as well as by the species of high trunk already mentioned at the beginning of the 19th century to consolidate the railway ballast.

Fauna

In the first part of the course, the unpolluted one, the fauna is very varied. In the Campo dei Fiori park you can meet ungulates such as deer or roe deer, and dozens of small mammals and rodents, including the red squirrel, hedgehog, fox, dormouse, shrew, vole, weasel, mole and various species of bats.

There are also several birds of prey: some resident like the northern goshawk, the black kite, the honey buzzard, the sparrow hawk and the peregrine falcon, others migratory such as the short-toed snake eagle and the marsh harrier. Other birds present are the owl, the tawny owl and the barn owl. The grey heron and many birds, migratory and not, typical of the woods and fields complete the avifauna.

Among the amphibians there are salamanders and various species of tree frogs, toads and frogs, while among the reptiles the lizard, the deaf adder, the viper and the lizard are common.

As far as invertebrates are concerned, the presence of the cave beetle, an endemic beetle of the Campo dei Fiori, is worthy of mention, and the dragonfly, the firefly, the stag beetle and the cicada.

The fish fauna is present in the initial stretch of the river, the least polluted one. The most common species are the brown trout and the european bullhead. In the Olona waters you can also find the common barbel, the chub, the gudgeon, the vairone, the common minnow, the common rudd and the bleak.

In 2010 the fish repopulation of the middle section of the river was attempted thanks to the introduction of fish coming from the Canale Villoresi. The initiative was unsuccessful due to a spill of polluting waste in 2012, which led to the death of the fish species previously introduced.

There are several alien species present. Among them, along the shores of the Olona, one can find the nutria, the American semiaquatic rodent, the spinycheek crayfish and the eastern gray squirrel, while in its waters it is possible to catch catfish.

Anthropic geography

Municipalities crossed

The municipalities crossed by the Olona are:

- Varese

- Valganna

- Induno Olona

- Malnate

- Lozza

- Vedano Olona

- Gornate Olona

- Castiglione Olona

- Castelseprio

- Lonate Ceppino

- Cairate

- Gorla Maggiore

- Fagnano Olona

- Gorla Minore

- Solbiate Olona

- Olgiate Olona

- Marnate

- Castellanza

- Legnano

- San Vittore Olona

- Canegrate

- Parabiago

- Nerviano

- Pogliano Milanese

- Vanzago

- Pregnana Milanese

- Rho

- Pero

- Milano

Seaworthiness and fishing

The river itself has never been a navigable communication route. It is not possible to speak of navigability even in the 21st century, even if in some points of the river canoeing is practiced and occasionally, for environmental promotion purposes, some ecologists carry out the descent by kayak.

Fishing was once a thriving activity that was also practiced by professional fishermen. In the Olona trout, crayfish, frogs and other fish species were fished. Individual fishing licenses were issued by the Olona river consortium. During the centuries, given the economic importance deriving from it, numerous regulations were enacted. The oldest document preserved in the archives of the Olona river consortium refers to a provision that prohibited fishing without a license (1602).

The fishing with nets and, from 1699, the "vivari" (or "nurseries"), that is those circular structures formed by stones that were destined to the breeding of the juvenile fish were also forbidden. The vivari were banned because they slowed the flow of water causing damage to the users who exploited the motive power of the river, like the millers. The vivari were built every year in the months of August and September, to then be emptied of fish and destroyed shortly before the beginning of Lent. In this way they provided the inhabitants' canteens with fish species at a time when meat was forbidden due to religious precepts.

Fishing activities along the Olona began to decline in the mid-nineteenth century due to the polluting discharges of the first industries, only to disappear completely between the two world wars due to the sharp deterioration of water quality.

Infrastructures and projects

The whole Olona is crossed by 57 bridges, among which there are some of historical interest, such as the Romanesque bridge in Castiglione Olona, and the iron bridge of Malnate, which was built at the end of the 19th century to allow the crossing of a railway. The largest infrastructure that crosses the Olona is instead the Cairate viaduct. Among the communication routes that cross the Olona, there are 2 railway lines (the Saronno–Laveno railway and the Como–Varese railway) and 7 provincial roads.

The course of the river, which is profoundly artificialized, is strongly at risk from a hydraulic point of view, that is, from flooding. After the completion in 2009 of the large Gurone rolling mill, Lura and Bozzente are of particular concern. Since 2006 the hydraulic defense works have been delegated to the aforementioned "river contract".

A railway line has been active along the Olona Valley. The Valmorea railway, this is its name, connected Castellanza to Switzerland following the course of the river. The passenger service was active from 1904 to 1952, while freight traffic was closed in 1977 due to competition from the railway line passing through Chiasso. A recovery project for tourism has been underway since 1990.

The construction of the Pedemontana motorway, which completely covered the Olona to the Vedano bridge, and the construction, along the course of the river, of various cycle paths should also be noted. Among them, it should be remembered that between Castellanza and Castiglione Olona, whose route follows the path of the Valmorea railway. The extension to Mendrisio, Switzerland is being planned for this cycle path.

Interesting sites

Water mills

Between the springs and Nerviano the course of the river was once scattered with water mills. Since the Middle Ages, along the Olona, the milling activity has flourished. Such was the number of mills to suggest that in the 15th century this activity constituted a considerable economic source for the whole area.

The oldest known document in which a mill is named on the Olona dates back to 1043: it refers to a milling plant located between Castegnate and the "Gabinella" locality in Legnano which was owned by Pietro Vismara. The Sforza and Visconti seigniories placed fortifications at the most important groupings of mills on the Olona, exploiting already existing fortresses and castles.

In 1608 there were 116 mills on the shores of the Olona, including a copper trip hammer, a fuller for clothes and several oil presses, a number which rose to 106 in 1772 and to 55 in 1881. In the years mentioned, the water wheels serving these milling plants (called, in Valle Olona, "rodigini") were, respectively, 463, 424 and 170.

Several of these mills have reached the 21st century. Some have been recovered, while others are in a state of neglect. Starting from the springs, the first historically significant milling plants that meet along the Olona are the Grassi mills in Varese, which were built between the 16th and 19th centuries. They have been restored to be used as a dwelling and have, on the external walls, some examples of sundials of great historical interest and a valuable fresco of 1675. Further south there are the Sonzini mills of Gurone, which are older than 1772. They remained in operation until 1970, after which they were used for housing. In Vedano Olona there is the mill at Fontanelle; already present in 1772, it had a millstone and a press. It underwent a first abandonment in the twenties, then it was restructured in the 1970s and again abandoned in the following decade.

The Bosetti mill is located in Castellazzo, a frazione in Fagnano Olona. Already registered as a Visconti mill in 1772, it was listed as a Ponte mill in 1857 before taking on its current name in the following years. In 1982 only the houses were accessible, while the rest was already abandoned. In Castelseprio there is the Zacchetto mill, which was active for agricultural purposes from the 18th to the 19th century. It became the first seat of the Pagani company (twenty years), and then it was transformed into a power plant. Since the 1980s it has been abandoned.

In Gornate Superiore, a frazione of Castiglione Olona, there is the Celeste mill. Formerly a Mariani mill in 1772 and a Guidali mill in 1857, it was registered under the current name in 1881. It had a millstone and oil presses. Since 1930 it has been adapted for private homes. The Taglioretti mill is located in Lonate Ceppino. Also in 1722, it was owned by Mariani. It took its current name in the 19th century. It was in service of the Canziani paper mill from 1901 and of the Samec cardboard factory from 1920. In 1982 it was abandoned.

In Gornate Olona there are the mills of Torba and San Pancrazio. Both existed before 1772, took the names of the respective fractions of 1857. Molinatory activities ceased around the middle of the 20th century. They are mostly used for housing. In Olgiate Olona there is instead the mill of Sasso. It is well preserved and therefore a project is underway that provides for the complete restoration of the hydraulic system.

In Legnano the seven mills of the city center were demolished by the big cotton industries to allow the installation of the most modern and efficient hydraulic wheels. In Legnanese there are only six: these are the Cornaggia of Legnano, Meraviglia (formerly Melzi Salazar), Cozzi, De Toffol, Montoli of San Vittore Olona and Galletto of Canegrate mills. The only mill in this area with still efficient mills is the mill attached to the Meraviglia farm in San Vittore Olona, which is certainly the oldest among the remaining ones: it dates back to the 14th century. This milling plant is still intended to grind livestock forage. An international cross country running, the Cinque Mulini, which takes place every year in the spring in San Vittore Olona takes its name from these milling plants. Downstream of Canegrate there are only a few others, such as the Gajo-Lampugnani mill in Parabiago, the Star Qua of Nerviano mill and the Sant'Elena mill in Pregnana Milanese.

Referring instead to the territory of Rho, we can cite among the examples in disuse or converted over the years into housing modules the Prepositural mill, once owned by the Parish of San Vittore and now completely abandoned, followed more downstream by the Cecchetti mill, transformed into a dwelling despite having preserved some elements of the machinery on display in the garden, in addition to the Nuovo mill, located at the confluence with the Bozzente stream and which also became a private residence.

Industrial archeology

From the 1960s and 1970s, the industry of the Valle Olona (especially the textile sector) entered an irreversible crisis and therefore, progressively, most of the factories definitively interrupted the productive activities, leaving the areas adjacent to the Olona an important heritage of industrial archeology.

Equipped with great architectural value is the Birrificio Angelo Poretti of Induno Olona, which was founded in 1877. In 1901 this industrial complex was expanded with the construction of new Liberty style pavilions. Even the subsequent restorations and extensions were respectful of this architectural choice. The buildings, between naturalism, classicism, Egyptian and floral, present striking decorations: masks, grotesques, medallions, fringes and drops, shells, giant pilasters and large festoons of hops. This establishment, originally, exploited the aforementioned Fontana degli Ammalati, or a resurgence whose water was used for centuries for its healing qualities.

Further down the valley there is the former Cotonificio Milani of Castiglione Olona. In addition to production facilities, this industrial complex includes a manor house and some workers' houses. It is located near the Valmorea railway. Also in Castiglione Olona, there are also the former factories of the Pettinificio Mazzucchelli, whose structures date back to 1849.

In Lonate Ceppino there are the former Oleificio Lepori and the former Pettinificio Clerici, both prior to 1772. In Fagnano Olona there are the former Cotton Factory Candiani, which dates from the beginning of the 20th century, the Filatura Introizzi, which was founded before 1881, and the former factories of the Vita Mayer paper mill. In the municipality of Solbiate Olona you can find the former establishments of Cotonificio Ponti. This industrial complex was founded in 1908 on a previous spinning started in 1823. In Olgiate Olona, on the other hand, there is the former Sanitaria Ceschina, or a garzificio that was built between 1902 and 1907.

Two of the former Cotonificio Cantoni facilities are located in Legnano and Castellanza. The first nucleus of the plant of Legnano was started in 1830; this factory was partly demolished, and the remaining buildings were converted into a shopping center. The former Cantoni Cotton Mill of Castellanza was instead used, in 1991, as the headquarters of the University Carlo Cattaneo.

Parks

Since the second half of the 20th century, there have been several protected natural areas established along the shores of the Olona. The Campo dei Fiori Regional Park covers an area of 6,300 hectares and is managed by a consortium formed by the Valli del Verbano mountain community, the Piambello mountain community, the province of Varese and the seventeen municipalities included in the Park territory: Barasso, Bedero Valcuvia, Brinzio, Casciago, Castello Cabiaglio, Cocquio-Trevisago, Comerio, Cunardo, Cuvio, Gavirate, Induno Olona, Luvinate, Masciago Primo, Orino, Rancio Valcuvia, Valganna and Varese. It is based in Brinzio and was established in 1984. Since 2010, the project to restore the Olona main spring area to the Rasa of Varese has been active.

The Parco Rile Tenore Olona, which was established in 2006, embraces a territory characterized by extensive terracing of fluvial-glacial origin, the so-called moraine plains, and is rich in sites of historical and cultural significance. The typical geology of the territory allows the birth of many small streams supported by spring and rain waters. The main ones are the Rile and the Tenore. The park covers 16 km² and includes the municipalities of Cairate, Carnago, Caronno Varesino, Castelseprio, Castiglione Olona, Gazzada Schianno, Gornate Olona, Lonate Ceppino, Lozza, Morazzone and Oggiona con Santo Stefano.

The Parco Valle del Lanza, born in 2002, includes the municipalities of Malnate, Cagno, Bizzarone and Valmorea. Of particular interest is the area crossed by the Lanza stream (another name for Gaggiolo), from which it takes its name. It has an area of 676 hectares.

In 2006 the Parco del Medio Olona was also established, which includes the stretch of the Valle Olona between Fagnano Olona and Marnate. The park includes the municipalities of Fagnano Olona, Gorla Maggiore, Solbiate Olona, Gorla Minore, Olgiate Olona and Marnate. In addition to the Valle Olona, the park also includes the Fagnanese stretch of the Tenore and the woods to the east of Gorla Maggiore, where the Fontanile di Tradate flows.

The Parco castello of Legnano, born in 1976, stands next to the castle of Legnano, on the border with the municipalities of Canegrate and San Vittore Olona. It is also known as "park castle" or "park of Legnano". In the period of its constitution, the reforestations were not founded on the knowledge of the local species, and therefore this protected area includes many non-native plants of the area. In 1981 a wetland was created that is frequented by a large number of aquatic birds and is inhabited by many fish species.

The Parco dei Mulini, which was established on 20 March 2008, covers the wooded and agricultural areas of the municipalities of Legnano, Canegrate, San Vittore Olona, Parabiago and Nerviano. The surface, over 264 hectares, is almost entirely used for agricultural activities. In the park there are important historical testimonies such as the castle of Legnano, the former Visconti di Modrone factory and six water mills (it. "mulini ad acqua"), the last testimony of the ancient milling tradition of the area.

Citations

- ^ "Catalogo editoriale 2003-2014" (PDF). Retrieved 20 August 2014.

- ^ Urona and Uòna are the two toponyms that refer to the river, respectively in Legnanese dialect and bustocco. See the text of D'Ilario (1984) on p. 186.

- ^ "Regione Lombardia - ARPA - Il fiume Olona - Inquadramento ambientale" (PDF). Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ "Regione Lombardia - ARPA - Contratto di fiume Olona Bozzente Lura - Rapporto del primo anno di lavoro" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ "Valleolona - Il Fiume Olona: Carta d'identità". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ Macchione 1998, p. 19.

- ^ "Valleolona - Il Fiume Olona: Storia". Archived from the original on 28 March 2015. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ "Legambiente Lombardia - L'Olona". ita.arpalombardia.it. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ "Metropolitana Milanese - Il funzionamento degli impianti di Milano Nosedo e Milano San Rocco". Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ Macchione 1998, p. 17.

- ^ Macchione 1998, p. 11 e 18.

- ^ Boscolo 2012, p. 79.

- ^ "Consorzio villoresi - Canali di competenza del consorzio" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ "Contratti di fiume - Ricostruzione dei corsi d'acqua dell'ambito vallivo di Olona, Bozzente, Lura: riconnessione con l'Olona inferiore fino al Po" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 August 2014. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ "Archeologia industriale in Lombardia - Scheda Nr.410 -Fornaci della Riana". Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- ^ "Assolaghi - Federazione nazionale centri di pesca - A.P.S. Fonteviva A.S.D." Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ "Varesefocus - Periodico dell'Unione industriali della provincia di Varese - Dove Venere fa ancora il bagno". Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ "Cascate della Valganna". Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ^ "Un ecomuseo per la Valle Olona". Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ "Fiume Olona - Carta d'identità". Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ Macchione 1998, p. 20.

- ^ D'Ilario 1984, p. 40.

- ^ See the two topographies of Legnano (dated 1925 and 1938) which are present in the text of D'Ilario on p. 352 and on p. 353.

- ^ "Fiume Olona - Inquadramento ambientale - ARPA Lombardia" (PDF). Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ "Provincia del Ticino - Il canale scolmatore nord-ovest". Archived from the original on 12 August 2014. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ "Centro geofisico prealpino - Eventi di piena del Lago Maggiore - Piena ed alluvione del novembre 2002". Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ A.A. V.V. Istituto Geografico De Agostini - Atlante Stradale d'Italia - 2005-2006.

- ^ "L'Olona, il fiume di Milano". Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ "Impianti di depurazione delle acque reflue "Milano San Rocco" e "Milano Nosedo"". Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 August 2014. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ "Regione Lombardia - Documento sullo stato dell'Olona e del Lambro Meridionale" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 August 2014. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ "La valle del fiume Olona - CCIAA di Varese" (PDF). Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ Macchione 1998, p. 21.

- ^ "Storia di Milano - La rete fognaria di Milano". Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ "Storie e rilievi dei canali esistenti" (PDF). Retrieved 15 August 2014.

- ^ D'Ilario 1984, p. 188.

- ^ Regional Technical Map 1: 10,000 Milan-Pavia.

- ^ "Ambito vallivo dell'Olona" (PDF). Retrieved 17 February 2017.

- ^ "Terra ri-genera cittài" (PDF). Retrieved 17 February 2017.

- ^ "I canali di Milano (1ª parte)". Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ^ "La Darsena - Vecchia Milano". Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ "Milano città acquatica e il suo porto di mare". Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- ^ "Milano – I Fiumi nascosti di Milano". Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- ^ Poggi 1911, p. 178.

- ^ "Regione Lombardia - ARPA - Contratto di fiume Olona Bozzente Lura - Attività di supporto ai processi negoziali "Verso i contratti di fiume" Bacino Olona-Lambro" (PDF). Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ^ Daniel Stopendal "Thesaurus Antiquitarum Instoriarum Italiae, Leida, 1704

- ^ Giuseppe Filippini, Iconografia del Castello e della città di Milano, 1722

- ^ Map of Milan, Artaria Sacchi, 1904

- ^ IGM, Map of Milan, July 1925

- ^ "Canottieri Olona, dopo la crisi un occhio al sociale". Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- ^ "Aspetti climatici della zona attraversata dall'Olona - ARPA Lombardia" (PDF). Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ "Comune di Milano - Parco Don Giussani (ex Parco Solari)". Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ D'Ilario 1984, pp. 186–187.

- ^ Macchione 1998, p. 27.

- ^ Di Maio 1998, p. 76.

- ^ Macchione 1998, p. 24.

- ^ Agnoletto 1992, p. 31.

- ^ Agnoletto 1992, p. 21.

- ^ Di Maio 1999, pp. 76–77.

- ^ Di Maio 1999, p. 26 e 83.

- ^ Di Maio 1999, p. 26.

- ^ "Le palafitte di Varese, patrimonio dell'UNESCO". Archived from the original on 26 August 2014. Retrieved 21 August 2014.

- ^ D'Ilario 1984, p. 6.

- ^ Di Maio 1999, p. 83.

- ^ Di Maio 1999, p. 14.

- ^ Agnoletto 1992, p. 14.

- ^ Agnoletto 1992, p. 19.

- ^ Di Maio 1998, pp. 27–30.

- ^ Di Maio 1998, p. 86.

- ^ Di Maio 1998, p. 100.

- ^ Agnoletto 1992, p. 18.

- ^ Di Maio 1992, p. 87.

- ^ Di Maio 1998, p. 88.

- ^ Agnoletto 1992, p. 23.

- ^ Di Maio 1998, p. 90.

- ^ Di Maio 1998, p. 89.

- ^ Di Maio 1998, p. 91.

- ^ "Varese Land of tourism - sito ufficiale del turismo e degli eventi in provincia di Varese". Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ Autori vari 2014, p. 14.

- ^ Agnoletto 1998, p. 38.

- ^ Agnoletto 1998, p. 32.

- ^ "Valle Olona". Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ Macchione 1998, p. 35.

- ^ D'Ilario 1984, p. 31.

- ^ Agnoletto 1992, p. 38.

- ^ Macchione 1998, p. 30.

- ^ "Castello di Fagnano Olona". Archived from the original on 8 September 2014. Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- ^ "Comune di Olgiate Olona". Retrieved 17 September 2014.

- ^ The castle of Belforte, of Induno, of Castiglione, of Fagnano, the Castellazzo of Ierago, of Castellanza in defense of the Guado di Castegnate, of Legnano and of Nerviano.

- ^ "Milano città acquatica e il suo porto di mare". Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ D'Ilario 1984, p. 191.

- ^ "Il Consorzio del fiume Olona - Storia". Retrieved 21 August 2014.

- ^ Macchione 1998, p. 77.

- ^ "Consorzio del fiume Olona". Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ Di Maio 1998, p. 85.

- ^ Macchione 1998, p. 84.

- ^ Macchione 1998, p. 85.

- ^ D'Ilario 1984, p. 84.

- ^ "Tesi di Patrizia Miramonti sull'ex area Cantoni". legnano.org. Archived from the original on 17 May 2006. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ Macchione 1998, p. 122.

- ^ D'Ilario 1984, p. 200.

- ^ Macchione 1998, p. 123.

- ^ Macchione 1998, p. 131.

- ^ D'Ilario 1984, p. 101.

- ^ "Olóna". Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ^ "Vela". Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ^ Macchione 1998, p. 324.

- ^ Macchione 1998, p. 26.

- ^ Agrati 1982, p. 6.

- ^ "Porta Comasina". Retrieved 29 November 2018.

- ^ Macchione 1998, p. 310.

- ^ Macchione 1998, p. 75.

- ^ Macchione 1998, p. 42.

- ^ Macchione 1998, p. 44.

- ^ Macchione 1998, p. 45.

- ^ Vecchio 2001, p. 169.

- ^ "Parco Rile Tenore Olona". castiglioneolona.it. Archived from the original on 15 July 2007. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ D'Ilario 1984, p. 195.

- ^ Macchione 1998, p. 12.

- ^ Macchione 1998, p. 25.

- ^ Macchione 1998, p. 121.

- ^ Vittore e Claudio Buzzi, Le vie di Milano, dizionario di toponomastica milanese, Ulrico Hoepli, Milano, 2005.

- ^ The cartographic references are taken from "Carte di Lombardia" by Giovanni Liva and Mario Signori, Graphic Arts Amilcare Pizzi for Mediocredito Lombardo, Milan, 1985, from "Historical Atlas of Milan, City of Lombardy" curated by Virgilio Vercelloni, Workshop of graphic art Lucini for Metropolitana Milanese, Milan 1987.

- ^ "Miol - Mappe storiche". Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ Macchione 1998, pp. 24–25.

- ^ "L'archivio storico del Consorzio del fiume Olona". Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ Macchione 1998, p. 48.

- ^ Macchione 1998, p. 65.

- ^ "Sperimentazione di modelli progettuali-tipo per la riqualificazione fluviale: il caso del F. Olona a Nerviano" (PDF). Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ Macchione 1998, p. 70.

- ^ Macchione 1998, p. 74.

- ^ Macchione 1998, pp. 76–77.

- ^ "Parco Rile Tenore Olona - L'Olona". Archived from the original on 12 August 2014. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ "Parco Rile Tenore Olona - La località Crotto". Archived from the original on 12 August 2014. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ Macchione 1998, pp. 22–24.

- ^ Macchione 1998, p. 22.

- ^ "Parco Rile Tenore Olona - Lo stagno Buzonel". Archived from the original on 12 August 2014. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ D'Ilario 1984, p. 193.

- ^ "Centro geofisico prealpino - Varese - Bilancio della stagione autunnale 2000" (PDF). Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ "Maltempo, Varese sott'acqua - Esonda l'Olona". Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- ^ Macchione 1998, p. 60.

- ^ Macchione 1998, p. 49.

- ^ "Varesefocus - Periodico dell'Unione industriali della provincia di Varese - Una diga per fermare la furia dell'Olona". varesenews.it. Archived from the original on 23 May 2014. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ Macchione 1998, p. 50.

- ^ Macchione 1998, p. 51.

- ^ "Comune di Gorla Maggiore - Archivio storico Luigi Carnelli". Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- ^ Macchione 1998, p. 68.

- ^ Macchione 1998, p. 69.

- ^ Macchione 1998, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Macchione 1998, pp. 71–72.

- ^ Macchione 1998, p. 71.

- ^ "La ciclabile dell'ingegnere: Canale Villoresi". Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- ^ Macchione 1998, p. 72.

- ^ "Fiume Olona". castiglioneolona.it. Archived from the original on 15 July 2007. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ "Qualità ambientale nelle aree metropolitane italiane - II Rapporto annuale - Qualità dell'ambiente urbano" (PDF). areeurbane.apat.it. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 May 2006. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ "Marsico: "Migliora la qualità delle acque dell'Olona"". Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- ^ "Accordo quadro di sviluppo territoriale - Contratto di Fiume Olona-Bozzente-Lura" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 May 2010. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ "Il Contratto di Fiume". Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- ^ "Gli impianti di depurazione delle acque reflue lungo il fiume Olona". Retrieved 4 September 2014.

- ^ "Regione Lombardia - Programma di tutela e uso delle acque in Lombardia" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 August 2014. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ "Contratti di Fiume - Ultimato il depuratore di Gornate Olona". Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 January 2012. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ "Parco Campo dei Fiori - Flora, fauna e aspetti del territorio". Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ "Parco Regionale del Campo dei Fiori". Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ "Parco Rile Tenore Olona - Home page". Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ "Parco del medio Olona - Boschi di latifoglie submontani degradati". Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ "Parco medio Olona - Programma pluriennale degli interventi" (PDF). Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ "Parco dei Mulini - Ecomuseo del paesaggio di Parabiago". Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ "Geologia e geomorfologia". Retrieved 12 September 2014.

- ^ "Carta ittica - Gli ambienti acquatici e i pesci della provincia di Varese". Retrieved 12 September 2014.

- ^ "Strage di pesci nell'Olona". Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- ^ "Le località lungo il fiume". Retrieved 7 September 2014.

- ^ D'Ilario 1984, p. 192.

- ^ "La navigabilità - Consorzio del fiume Olona". Retrieved 14 August 2014.

- ^ "Olona - Il fiume, la civiltà, il lavoro". Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ^ "Un inquinamento a norma di legge" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ^ Macchione 1998, p. 103.

- ^ "Olona fiume di civiltà". Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ^ "Consorzio del fiume Olona - Licenza di pesca del 1833" (PDF). Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ^ Macchione 1998, pp. 103–105.

- ^ Macchione 1998, p. 104.

- ^ Macchione 1998, p. 105.

- ^ Macchione 1998, p. 41.

- ^ Macchione 1998, pp. 103–104.

- ^ Macchione 1998, p. 29.

- ^ ""Obiettivo Olona" - Legambiente Lombardia" (PDF). Retrieved 14 August 2014.

- ^ "Rischio frane. È Allarme per il dissesto idrogeologico". Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ "Vasche di laminazione: effetti più negativi che positivi". Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ "Parco del Lura - Home Page". legnanonews.com. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ "Il Bozzente esonda sul Sempione". varesenews.it. Archived from the original on 12 August 2014. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ "Contratti di Fiume - Studi di scenario Olona-Bozzente-Lura". Archived from the original on 13 February 2010. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- ^ Macchione 1998, p. 31.

- ^ "Ferrovia della Valmorea". Retrieved 4 September 2014.

- ^ "Valmorea - Una storia nata nel 1904 e risorta nel 1990". Retrieved 4 September 2014.

- ^ Macchione 1998, p. 34.

- ^ "In bicicletta lungo la Valle Olona". Archived from the original on 5 July 2014. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ D'Ilario 1984, p. 197.

- ^ Macchione 1998, p. 120.

- ^ Macchione 1998, p. 323.

- ^ "L'ombra dello gnomone". Retrieved 7 September 2014.

- ^ "Archeologia industriale in Lombardia - Scheda Nr.838 -Mulini Grassi". Retrieved 7 September 2014.

- ^ "Archeologia industriale in Lombardia - Scheda Nr.412 -Mulini Grassi". Retrieved 7 September 2014.

- ^ Macchione 1998, p. 277.

- ^ "Archeologia industriale in Lombardia - Scheda Nr.405 -Mulini Sonzini". Retrieved 7 September 2014.

- ^ "I vecchi mulini di Gurone". varesenews.it. Retrieved 7 September 2014.

- ^ "Archeologia industriale in Lombardia - Scheda Nr.431 - Mulino alle Fontanelle". Retrieved 7 September 2014.

- ^ "Archeologia industriale in Lombardia - Scheda Nr.377 - Mulino Bosetti". Retrieved 7 September 2014.

- ^ "Archeologia industriale in Lombardia - Scheda Nr.812 - Mulino Zacchetto". Retrieved 7 September 2014.

- ^ "Archeologia industriale in Lombardia - Scheda Nr.367 - Centrale Zacchetto - Ex Mulino Zacchetto". Retrieved 7 September 2014.

- ^ "Archeologia industriale in Lombardia - Scheda Nr.371 - Mulino del Celeste". Retrieved 7 September 2014.

- ^ "Archeologia industriale in Lombardia - Scheda Nr.816 - Mulino del Celeste". Retrieved 7 September 2014.

- ^ "Archeologia industriale in Lombardia - Scheda Nr.392 - Mulino Taglioretti". Retrieved 7 September 2014.

- ^ "Archeologia industriale in Lombardia - Scheda Nr.821 - Mulini San Pancrazio". Retrieved 7 September 2014.

- ^ "Archeologia industriale in Lombardia - Scheda Nr.822 - Mulini di Torba". Retrieved 7 September 2014.

- ^ "Archeologia industriale in Lombardia - Scheda Nr.385 - Mulini di S. Pancrazio". Retrieved 7 September 2014.

- ^ "Archeologia industriale in Lombardia - Scheda Nr.386 - Mulini di Torba". Retrieved 7 September 2014.

- ^ "Mulino del "Sasso", dal recupero l'energia pulita". varesenews.it. Archived from the original on 14 October 2010. Retrieved 7 September 2014.

- ^ "Mulino day 14 giugno 2015". Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- ^ Paola Pessina e Giuseppe Terruzzi, Le campagne e il borgo di Rho nei documenti del Catasto di Maria Teresa d'Austria, Biblioteca Popolare di Rho, 1980

- ^ "Dalla Macina al Micro Hydro - Riqualificazione tecnologica e funzionale del Mulino Galletto" (PDF). Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ "Comune di Induno olona - Il Liberty e la Birreria Poretti". Archived from the original on 20 October 2014. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ "Archeologia industriale in Lombardia - Scheda Nr.389 -Fabbrica di Birra Splugen - Poretti". Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- ^ Macchione 1998, pp. 157–159.