Pharaoh

In the early dynasties, ancient Egyptian kings had as many as three titles: the Horus, the Sedge and Bee (nswt-bjtj), and the Two Ladies or Nebty (nbtj) name. The Golden Horus and the nomen and prenomen titles were added later.

In Egyptian society, religion was central to everyday life. One of the roles of the king was as an intermediary between the deities and the people. The king thus was deputised for the deities in a role that was both as civil and religious administrator. The king owned all of the land in Egypt, enacted laws, collected taxes, and served as commander-in-chief of the military. Religiously, the king officiated over religious ceremonies and chose the sites of new temples. The king was responsible for maintaining Maat (mꜣꜥt), or cosmic order, balance, and justice, and part of this included going to war when necessary to defend the country or attacking others when it was believed that this would contribute to Maat, such as to obtain resources.

During the early days prior to the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt, the Deshret or the "Red Crown", was a representation of the kingdom of Lower Egypt, while the Hedjet, the "White Crown", was worn by the kings of Upper Egypt. After the unification of both kingdoms, the Pschent, the combination of both the red and white crowns became the official crown of the pharaoh. With time new headdresses were introduced during different dynasties such as the Khat, Nemes, Atef, Hemhem crown, and Khepresh. At times, a combination of these headdresses or crowns worn together was depicted.

Etymology

The word pharaoh ultimately derives from the Egyptian compound pr ꜥꜣ, */ˌpaɾuwˈʕaʀ/ "great house", written with the two biliteral hieroglyphs pr "house" and ꜥꜣ "column", here meaning "great" or "high". It was the title of the royal palace and was used only in larger phrases such as smr pr-ꜥꜣ "Courtier of the High House", with specific reference to the buildings of the court or palace. From the Twelfth Dynasty onward, the word appears in a wish formula "Great House, May it Live, Prosper, and be in Health", but again only with reference to the royal palace and not a person.

Sometime during the era of the New Kingdom, pharaoh became the form of address for a person who was king. The earliest confirmed instance where pr ꜥꜣ is used specifically to address the ruler is in a letter to the eighteenth dynasty king, Akhenaten (reigned c. 1353–1336 BCE), that is addressed to "Great House, L, W, H, the Lord". However, there is a possibility that the title pr ꜥꜣ first might have been applied personally to Thutmose III (c. 1479–1425 BCE), depending on whether an inscription on the Temple of Armant may be confirmed to refer to that king. During the Eighteenth dynasty (sixteenth to fourteenth centuries BCE) the title pharaoh was employed as a reverential designation of the ruler. About the late Twenty-first Dynasty (tenth century BCE), however, instead of being used alone and originally just for the palace, it began to be added to the other titles before the name of the king, and from the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty (eighth to seventh centuries BCE, during the declining Third Intermediate Period) it was, at least in ordinary use, the only epithet prefixed to the royal appellative.

From the Nineteenth dynasty onward pr-ꜥꜣ on its own, was used as regularly as ḥm, "Majesty". The term, therefore, evolved from a word specifically referring to a building to a respectful designation for the ruler presiding in that building, particularly by the time of the Twenty-Second Dynasty and Twenty-third Dynasty.

The first dated appearance of the title "pharaoh" being attached to a ruler's name occurs in Year 17 of Siamun (tenth century BCE) on a fragment from the Karnak Priestly Annals, a religious document. Here, an induction of an individual to the Amun priesthood is dated specifically to the reign of "Pharaoh Siamun". This new practice was continued under his successor, Psusennes II, and the subsequent kings of the twenty-second dynasty. For instance, the Large Dakhla stela is specifically dated to Year 5 of king "Pharaoh Shoshenq, beloved of Amun", whom all Egyptologists concur was Shoshenq I—the founder of the Twenty-second Dynasty—including Alan Gardiner in his original 1933 publication of this stela. Shoshenq I was the second successor of Siamun. Meanwhile, the traditional custom of referring to the sovereign as, pr-ˤ3, continued in official Egyptian narratives.

The title is reconstructed to have been pronounced *[parʕoʔ] in the Late Egyptian language, from which the Greek historian Herodotus derived the name of one of the Egyptian kings, Koinē Greek: Φερων. In the Hebrew Bible, the title also occurs as Hebrew: פרעה [parʕoːh]; from that, in the Septuagint, Koinē Greek: φαραώ, romanized: pharaō, and then in Late Latin pharaō, both -n stem nouns. The Qur'an likewise spells it Arabic: فرعون firʿawn with n (here, always referring to the one evil king in the Book of Exodus story, by contrast to the good king in surah Yusuf's story). The Arabic combines the original ayin from Egyptian along with the -n ending from Greek.

In English, the term was at first spelled "Pharao", but the translators for the King James Bible revived "Pharaoh" with "h" from the Hebrew. Meanwhile, in Egypt, *[par-ʕoʔ] evolved into Sahidic Coptic ⲡⲣ̅ⲣⲟ pərro and then ərro by rebracketing p- as the definite article "the" (from ancient Egyptian pꜣ).

Other notable epithets are nswt, translated to "king"; ḥm, "Majesty"; jty for "monarch or sovereign"; nb for "lord"; and ḥqꜣ for "ruler".

Functions

As a central figure of the state, the pharaoh was the obligatory intermediary between the gods and humans. To the former, he ensured the proper performance of rituals in the temples; to the latter, he guaranteed agricultural prosperity, the defense of the territory and impartial justice.

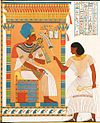

In the sanctuaries, the image of the sovereign is omnipresent through parietal scenes and statues. In this iconography, the pharaoh is invariably represented as the equal of the gods. In the religious speech, he is however only their humble servant, a zealous servant who makes multiple offerings. This piety expresses the hope of a just return of service. Filled with goods, the gods must favorably activate the forces of nature for a common benefit to all Egyptians. The only human being admitted to dialogue with the gods on an equal level, the Pharaoh was the supreme officiant; the first of the priests of the country. More widely, the pharaonic gesture covered all the fields of activity of the collective and ignored the separation of powers. Also, every member of the administration acts only in the name of the royal person, by delegation of power.

From the Pyramid Texts, the political actions of the sovereign were framed by a single maxim: "Bring Maat and repel Isfet", that is to say, promote harmony and repel chaos. As the nurturing father of the people, the Pharaoh ensured prosperity by calling upon the gods to regulate the waters of the Nile, by opening the granaries in case of famine and by guaranteeing a good distribution of arable land. Chief of the armies, the pharaoh was the brave protector of the borders. Like Ra who fights the serpent Apophis, the king of Egypt repels the plunderers of the desert, fights the invading armies and defeats the internal rebels. The Pharaoh was always the sole victor; standing up and knocking out a bunch of prisoners or shooting arrows from his battle chariot. As the only legislator, the laws and decrees he promulgated were seen as inspired by divine wisdom. This legislation, kept in the archives and placed under the responsibility of the vizier, applied to all, for the common good and social agreement.

Regalia

Scepters and staves

Sceptres and staves were a general symbol of authority in ancient Egypt. One of the earliest royal scepters was discovered in the tomb of Khasekhemwy in Abydos. Kings were also known to carry a staff, and Anedjib is shown on stone vessels carrying a so-called mks-staff. The scepter with the longest history seems to be the heqa-sceptre, sometimes described as the shepherd's crook. The earliest examples of this piece of regalia dates to prehistoric Egypt. A scepter was found in a tomb at Abydos that dates to Naqada III.

Another scepter associated with the king is the was-sceptre. This is a long staff mounted with an animal head. The earliest known depictions of the was-scepter date to the First Dynasty. The was-scepter is shown in the hands of both kings and deities.

The flail later was closely related to the heqa-scepter (the crook and flail), but in early representations the king was also depicted solely with the flail, as shown in a late pre-dynastic knife handle that is now in the Metropolitan museum, and on the Narmer Macehead.

The Uraeus

The earliest evidence known of the Uraeus—a rearing cobra—is from the reign of Den from the first dynasty. The cobra supposedly protected the king by spitting fire at its enemies.