Prick (slang)

Definition and general usage

Modern dictionaries agree on prick as a euphemism for 'penis'. But they offer some slight variations in the use of prick as an insult. The Concise New Partridge Dictionary of Slang says a prick is "a despicable man, a fool, used as a general term of offence or contempt. Often as an abusive form of address, always of a male or an inanimate object." Similarly the Oxford Dictionary of English says "a stupid or contemptible man". Merriam Webster offers "a spiteful or contemptible man often having some authority".

Peter Silverton notes that the way a person calls another person a prick, which can range from disdain to anger, will help to define its meaning: "Said lightly, it's a jerk or a bumbler. Said with a harsher, punchier intonation it can mean something far nastier. Say, 'Don't be such a prick' vs. 'You prick!'"

In modern times, writes Tony Thorne, "in polite company it is the least acceptable of the many terms for the male member (cock, tool, etc.), it is nevertheless commonly used, together with dick, by women in preference to those alternatives".

History

Middle Ages to 18th century

The word comes from the Middle English prikke, which originates in the Old English prica 'point, puncture, particle, small portion of space or time'. The meaning of prick as 'a pointed weapon' or 'dagger' is first noted in the 1550s. Prick as a verb for sexual intercourse can be seen as early as the 14th century, in Geoffrey Chaucer's Canterbury Tales. The Oxford English Dictionary records the first use of the word prick as 'penis' in 1592, although it was probably used in the spoken language for some time before. It was "probably coined with the image of a thorn in mind from the shape and image of penetration evoked", says Thorne. The earliest use of the noun prick as 'penis' is observed in the works of Shakespeare, who uses it playfully several times as a double entendre with the non-sexual meaning of prick, i.e., 'the act of puncturing', as in the following examples:

He that sweetest rose will find / must find love's prick and Rosalinde.

The bawdy hand of the dial is now upon the prick of noon.

In the 16th and 17th centuries, "my prick" was used as a term of endearment by "immodest maids" for their boyfriends.

The word is listed in Francis Grose's A Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue as "prick: the virile member" in 1788.

A popular saying during the 18th century was: "May your prick and your purse never fail you."

19th to 20th centuries

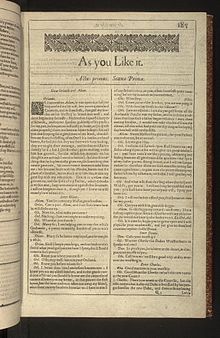

In the Victorian era, the slang form of prick was hidden away from most "respectable" literature. Even earlier, an 1807 edition of The Family Shakespeare eliminated the "prick" verse from As You Like It, and continued without it in subsequent editions. In 1861, at least one version of Shakespeare had replaced prick with thorn. However, prick continued to appear in Victorian pornography, such as Walter's My Secret Life, who used it 253 times, as well as in the works of Scottish poet Robert Burns, who used it with "vulgar good humour".

Prick started to take on the sense of 'fool' or 'contemptible person' in the 19th century, usually preceded by silly. "The semantic association between stupidity and terms for the penis is noticeably strong", notes Hughes. Silverton observes that "whereas the French place idiocy with the vagina, the Yiddish and English place it with the penis, with shmuck and prick."

In Farmer and Henley's A Dictionary of Slang and Colloquial English in 1905, the two definitions of prick are "a term of endearment (1540)", or "a pimple".

Most linguists cite 1929 in the United States as the time and place when prick began to be used as a direct insult, as in "You prick!" or "What a prick!" This was also the time when similar sexual euphemisms, like cunt (1928) and twat (1929), became direct insults. Dick's history is reversed: Dick as 'fool' has been recorded since the 16th century but as 'penis' only since about 1888. In The Life of Slang, Coleman notes the use of prick as 'a stupid or contemptible person' as early as 1882.

When used with the word silly, however, as in "Silly prick!", the word has continued to be viewed as fairly inoffensive.

Modern usage

Popular expressions

By the 20th and 21st centuries, several expressions related to prick were being used.

"To look at every woman through a hole in one's prick" refers to a man who views every woman as a potential instrument of sexual pleasure.

A short stout person has sometimes been described as "short and thick like a Welshman's prick."

In Cockney rhyming slang, a penis is described as a Hampton Wick, a Hampton or a wick because it rhymes with prick.

An English proverb says "A standing prick has no conscience".

Education

In Pedagogical Desire: Authority, Seducation, Transference, and the Question of Ethics, Jan Jagodzinski emphasizes the association of prick with authority figures in his chapter, "The Teacher as Prick", but also allows that teachers can refer to students as "little pricks".

Literature

By the mid-20th century, prick had enthusiastically returned to literature from its Victorian banishment, and was being used liberally both as a description for the penis and as an insult. Philip Roth used it frequently in Portnoy's Complaint, with an oft-cited quote being his inclusion of the Yiddish proverb "When the prick stands up, the brain gets buried." Darryl Ponicsan uses it to alliterative effect in "We can be just three sailors together, or we can be a prisoner and two pricks" in The Last Detail (1970). Norah Vincent demonstrates the use of prick as someone in authority in her book Voluntary Madness: "I'd been at the mercy of a prick on a power trip, the kind of buttoned-up bantam rooster who gets off on control and then, when you resist him, tells you that you've got issues with control." Larissa Dubecki continued the Shakespearean wordplay tradition with her 2015 book, Prick with a Fork: The World's Meanest Waitress Spills the Beans.

Media and entertainment

Prick is listed as a more mild "playground word" on The Guardian's list of TV's most offensive words.

It was included in "The Penis Song" in Monty Python's The Meaning of Life (1983): "Isn't it awfully nice to have a penis / Isn't it frightfully good to have a dong / It's swell to have a stiffy / It's divine to own a dick / From the tiniest little tadger to the world's biggest prick."

In 2007, Gloria Steinem proposed the terms prick flicks and prick lit as a separate category of films and literature for men, much as films and literature for women are described as chick flicks and chick lit. Roger Ebert responded by criticizing all such gender-based terms for either books or film as "sexist and ignorant".

Politics

John F. Kennedy was alleged to have said of then Canadian Prime Minister John Diefenbaker, "I didn't think Diefenbaker was a son of a bitch. I thought he was a prick."

When an unauthorized and unflattering biography by a former ally appeared of UK prime minister David Cameron, Cameron made a speech in which he mentioned a doctor's appointment he had and announced that "just a little prick, just a stab in the back" had summed up his day.

Psychology

In The Daughter's Seduction, a book that established Jane Gallop's reputation as a psychoanalytic critic, Gallop explores the difference between the phallus and the prick, including psychologist and scholar Jacques Lacan in her definition of the latter. Lacan is not just "phallocentric", she says, he is "phallo-eccentric. Or in more pointed language, he is a prick." She continues:

In vulgar, non-philosophical usage, the prick is both the male sexual organ (the famous penis of penis-envy: attraction-resentment) and an obnoxious person-an unprincipled and selfish man who high-handedly abuses others, who capriciously exhibits little or no regard for justice. Usually restricted to men, this epithet astoundingly often describes someone whom women (or men who feel the 'prick' of this man's power, men in a non-phallic position), despite themselves, find irresistible.

Unlike phallocentrism, which locates itself in a clear-cut polemic field where opposition conditions a certain good and evil, the prick is beyond good and evil, beyond the phallus. Phallocentrism and the polemic are masculine, upright matters. The prick, in some crazy way, is feminine. The prick does not play by the rules: he (she) is a narcissistic tease who persuades by means of attraction and resistance, not by orderly systemic discourse.

See also

References

- ^ Tom Dalzell, Terry Victor Routledge, The Concise New Partridge Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English, 27 November 2014.

- ^ Angus Stevenson, Oxford Dictionary of English, OUP Oxford, 19 August 2010.

- ^ "Prick | Definition of Prick". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 9 July 2017.

- ^ Peter Silverton, Filthy English: The How, Why, When And What Of Everyday Swearing, Portobello Books, 3 November 2011.

- ^ Tony Thorne, Dictionary of Contemporary Slang, Bloomsbury Publishing, 27 February 2014.

- ^ "prick (n.)". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 9 July 2017.

- ^ Johnathan Green, The Vulgar Tongue, Green's History of Slang. p. 24.

- ^ Geoffrey Hughes, An Encyclopedia of Swearing: The Social History of Oaths, Profanity, Foul Language, and Ethnic Slurs in the English-speaking World, Routledge, 26 March 2015, p. 89.

- ^ Francis Grose, A Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue, S. Hooper, 1788.

- ^ Eric Partridge, The Routledge Dictionary of Historical Slang, Routledge, 2 September 2003, p. 288.

- ^ Peter Silverton, Filthy English: The How, Why, When And What Of Everyday Swearing, Portobello Books, 3 November 2011.

- ^ Farmer and Henley, A Dictionary of Slang and Colloquial English, 1905, p. 352.

- ^ Julie Coleman, The Life of Slang, OUP Oxford, 8 March 2012.

- ^ Jan Jagodzinski,Pedagogical Desire: Authority, Seducation, Transference, and the Question of Ethics, IAP, 2006.

- ^ Norah Vincent, Voluntary Madness: My Year Lost and Found in the Loony Bin, Penguin, 2008, p. 32.

- ^ Megan Mackander (8 September 2015). "Prick with a Fork: World's worst waitress Larissa Dubecki serves revenge cold in new book". ABC News (Australian Broadcasting Corporation). Retrieved 9 July 2017.

- ^ Extract from Language and Sexual Imagery in Broadcasting: A Contextual Investigation, The Guardian.

- ^ Gabriele Azzaro, Four-letter Films: Taboo Language in Movies, Aracne, 2005.

- ^ Jenny Colgan (13 July 2007). "Chick flicks or prick flicks, they're just films | Film". The Guardian. Retrieved 9 July 2017.

- ^ Roger Ebert, Roger Ebert's Movie Yearbook 2009, Andrews McMeel Publishing, 15 June 2009.

- ^ Wintour, Patrick (22 September 2015). "'Just a little prick': Cameron takes sideswipe at Ashcroft | Politics". The Guardian. Retrieved 9 July 2017.

- ^ Jane Gallop, The Daughter's Seduction: Feminism and Psychoanalysis, Cornell University Press, May 1, 1982.