Principality Of Wales

The Principality was formally founded in 1216 by native Welshman and King of Gwynedd, Llywelyn the Great who gathered other leaders of pura Wallia at the Council of Aberdyfi. The agreement was later recognised by the 1218 Treaty of Worcester between Llywelyn the Great of Wales and Henry III of England. The treaty gave substance to the political reality of 13th-century Wales and England, and the relationship of the former with the Angevin Empire. The principality retained a great degree of autonomy, characterized by a separate legal jurisprudence based on the well-established laws of Cyfraith Hywel, and by the increasingly sophisticated court of the House of Aberffraw. Although it owed fealty to the Angevin king of England, the principality was de facto independent, with a similar status in the empire to the Kingdom of Scotland. Its existence has been seen as proof that all the elements necessary for the growth of Welsh statehood were in place.

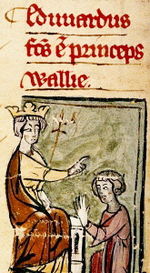

The period of de facto independence ended with Edward I's conquest of the principality between 1277 and 1283. Under the Statute of Rhuddlan, the principality lost its independence and became effectively an annexed territory of the English crown. From 1301, the crown's lands in north and west Wales formed part of the appanage of England's heir apparent, with the title "Prince of Wales". On accession of the prince to the English throne, the lands and title became merged with the Crown again. On two occasions Welsh claimants to the title rose up in rebellion during this period, although neither ultimately succeeded.

Since the Laws in Wales Acts 1535–1542, which formally incorporated all of Wales within the Kingdom of England, there has been no geographical or constitutional basis for describing any of the territory of Wales as a principality, although the term has occasionally been used in an informal sense to describe the country, and in relation to the honorary title of Prince of Wales.

Pre-conquest principality

The Principality of Wales was created in 1216 at the Council of Aberdyfi when it was agreed between Llywelyn the Great and the other sovereign princes among the Welsh that he was the paramount ruler amongst them, and they would pay homage to him. Later he obtained recognition, at least in part, of this agreement from the King of England, who agreed that Llywelyn's heirs and successors would enjoy the title "Prince of Wales" but with certain limitations to his realm and other conditions, including homage to the King of England as vassal, and adherence to rules regarding a legitimate succession. Llywelyn had been at pains to ensure that his heirs and successors would follow the "approved" (by the Pope at least) system of inheritance which excluded illegitimate sons. In so doing he excluded his elder bastard son Gruffydd ap Llywelyn from the inheritance, a decision which would have later ramifications. In 1240 Llywelyn died and Henry III of England (who succeeded John) promptly invaded large areas of his former realm, usurping them from him. However, the two sides came to peace and Henry honoured at least part of the agreement and bestowed upon Dafydd ap Llywelyn the title 'Prince of Wales'. This title would be granted to his successor Llywelyn in 1267 (after a campaign by him to achieve it) and was later claimed by his brother Dafydd and other members of the princely House of Aberffraw.

Aberffraw princes

Llywelyn ap Iorwerth 1195–1240

By 1200 Llywelyn Fawr (the Great) ap Iorwerth ruled over all of Gwynedd, with England endorsing all of Llywelyn's holdings that year. England's endorsement was part of a larger strategy of reducing the influence of Powys Wenwynwyn, as King John had given William de Breos licence in 1200 to "seize as much as he could" from the native Welsh. However, de Breos was in disgrace by 1208, and Llywelyn seized both Powys Wenwynwyn and northern Ceredigion.

In his expansion, the Prince was careful not to antagonise King John, his father-in-law. Llywelyn had married Joan, King John's illegitimate daughter, in 1204. In 1209 Prince Llywelyn joined King John on his campaign in Scotland. However, by 1211 King John recognised the growing influence of Prince Llywelyn as a threat to English authority in Wales. King John invaded Gwynedd and reached the banks of the Menai, and Llywelyn was forced to cede the Perfeddwlad, and recognize John as his heir presumptive if Llywelyn's marriage to Joan did not produce any legitimate successors. Succession was a complicated matter given that Welsh law recognized children born out of wedlock as equal to those in born in wedlock and sometimes accepted claims through the female line. By then, Llywelyn had several illegitimate children. Many of Llywelyn's Welsh allies had abandoned him during England's invasion of Gwynedd, preferring an overlord far away rather than one nearby. Welsh lords expected an unobtrusive English crown, but King John had a castle built at Aberystwyth, and his direct interference in Powys and the Perfeddwlad caused many of these Welsh lords to rethink their position. Llywelyn capitalised on Welsh resentment against King John, and led a church-sanctioned revolt against him. As King John was an enemy of the church, Pope Innocent III gave his blessing to Llywelyn's revolt.

Early in 1212 Llywelyn had regained the Perfeddwlad and burned the castle at Aberystwyth. Llywelyn's revolt caused John to postpone his invasion of France, and Philip Augustus, the King of France, was so moved as to contact Llywelyn and propose that they ally against the English king, King John ordered the execution by hanging of his Welsh hostages, the sons of many of Llywelyn's supporters, Llywelyn I was the first prince to receive the fealty of other Welsh lords at the 1216 Council of Aberdyfi, thus becoming the de facto Prince of Wales and giving substance to the Aberffraw claims.

Dafydd ap Llywelyn 1240–46

On succeeding his father, Dafydd immediately had to contend with the claims of his half-brother, Gruffudd, to the throne. Having imprisoned Gruffudd, his ambitions were curbed by an invasion of Wales led by Henry III in league with a number of the captive Gruffudd's supporters. In August 1241, Dafydd capitulated and signed the Treaty of Gwerneigron, further restricting his powers. By 1244, however, Gruffudd was dead, and Dafydd seems to have benefited from the backing of many of his brother's erstwhile supporters. He was acknowledged by the Pope as Prince of Wales for a time and defeated Henry III in battle in 1245 during the English king's second invasion of Wales. A truce was agreed in the autumn, and Henry withdrew, but Dafydd died unexpectedly in 1246 without issue. His wife, Isabella de Braose, returned to England; she was dead by 1248.

Dafydd married Isabella de Braose in 1231. Their marriage produced no children, and there is no contemporary evidence that Dafydd sired any heirs. According to late genealogical sources collected by Bartrum (1973), Dafydd had two children by an unknown woman (or women), a daughter, Annes, and a son, Llywelyn ap Dafydd, who apparently later became Constable of Rhuddlan and was succeeded in that post by his son Cynwrig ap Llywelyn.

Owain Goch ap Gruffydd 1246–53 (d. 1282)

Following Dafydd's death, Gwynedd was divided between Owain Goch and his younger brother Llywelyn. This situation lasted until 1252 when their younger brother Dafydd ap Gruffudd reached his majority. Disagreement about how to further divide the realm led to conflict in 1253 in which Llywelyn was victorious. Owain spent the remainder of his days a prisoner of his brother.

Llywelyn ap Gruffudd 1246–82

After achieving victory over his brothers, Llywelyn went on to reconquer the areas of Gwynedd occupied by England (the Perfeddwlad and others). His alliance with Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester, in 1265 against King Henry III of England allowed him to reconquer large areas of mid-Wales from the English Marcher Lords. At the Treaty of Montgomery between England and Wales in 1267 Llywelyn was granted the title "Prince of Wales" for his heirs and successors and allowed to keep the lands he had conquered as well as the homage of lesser Welsh princes in return for his own homage to the King of England and payment of a substantial fee. Disputes between him, his brother Dafydd, and English lords bordering his own led to renewed conflict with England (now ruled by Edward I) in 1277. Following the Treaty of Aberconwy Llywelyn was confined to Gwynedd-uwch-Conwy. He joined a revolt instigated by his brother Dafydd in 1282 in which he died in battle.

Dafydd ap Gruffudd 1282–83

Dafydd assumed his elder brother's title in 1282 and led a brief period of continued resistance against England. He was captured and executed in 1283.

Government, administration and law

The political maturation of the principality's government fostered a more defined relationship between the prince and the people. Emphasis was placed on the territorial integrity of the principality, with the prince as lord of all the land, and other Welsh lords swearing fealty to the prince directly, a distinction with which the Prince of Wales paid yearly tribute to the King of England. By treaty, the principality was obliged to pay the kingdom large annual sums. Between 1267 and 1272 Wales made a total payment of £11,500, "proof of a growing money economy... and testimony of the effectiveness of the principality's financial administration," wrote historian Dr. John Davies. Additionally, modifications and amendments to the Law Codes of Hywel Dda encouraged the decline of the galanas (blood-fine) and the use of the jury system. The Aberffraw dynasty maintained vigorous diplomatic and domestic policies; and patronized the Church in Wales, particularly that of the Cistercian Order.

The princely court

At the end of the twelfth century, and beginning of the thirteenth century, Llywelyn ab Iorwerth (Llywelyn Fawr or Llywelyn the Great), built a royal home at Abergwyngregyn (known as Tŷ Hir, the Long House, in later documents) on the site of the subsequent manor house of Pen y Bryn. To the east was the newly endowed Cistercian Monastery of Aberconwy; to the west the cathedral city of Bangor. In 1211, King John of England brought an army across the river Conwy, and occupied the royal home for a brief period; his troops went on to burn Bangor. Llywelyn's wife, John's daughter Joan, also known as Joanna, negotiated between the two men, and John withdrew. Joan died at Abergwyngregyn in 1237; Dafydd ap Llywelyn died there in 1246; Eleanor de Montfort, Lady of Wales, wife of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, died there on 19 June 1282, giving birth to a baby, Gwenllian of Wales.

Population, culture and society

The 13th-century Principality of Wales encompassed three-quarters of the surface area of modern Wales; "from Anglesey to Machen, from the outskirts of Chester to the outskirts of Cydweli," wrote Davies. By 1271, Prince Llywelyn II could claim a growing population of about 200,000 people or a little less than three-quarters of the total Welsh population. The population increase was common throughout Europe in the 13th century, but in Wales it was more pronounced. By Llywelyn II's reign, as much as 10 percent of the population were town-dwellers. Additionally, "unfree slaves... had long disappeared" from within the territory of the principality, wrote Davies. The increase in men allowed the prince to call on and field a far more substantial army.

A more stable social and political environment provided by the Aberffraw administration allowed for the natural development of Welsh culture, particularly in literature, law, and religion. Tradition originating from The History of Gruffydd ap Cynan attributes Gruffydd I as reforming the orders of bards and musicians; Welsh literature demonstrated "vigor and a sense of commitment" as new ideas reached Wales, even in "the wake of the invaders", according to historian John Davies. Contacts with continental Europe "sharpened Welsh pride", wrote Davies in his History of Wales.

Economy and trade

The increase in the Welsh population, especially in the lands of the principality, allowed for a greater diversification of the economy. The Meirionnydd tax rolls give evidence to the thirty-seven various professions present in Meirionnydd directly before the conquest. Of these professions, there were eight goldsmiths, four bards (poets) by trade, 26 shoemakers, a doctor in Cynwyd, and a hotel keeper in Maentwrog, and 28 priests; two of whom were university graduates. Also present were a significant number of fishermen, administrators, professional men and craftsmen.

With the average temperature of Wales a degree or two higher than it is today, more Welsh lands were arable for agriculture, "a crucial bonus for a country like Wales," wrote the historian John Davies. Of significant importance for the principality included more developed trade routes, which allowed for the introduction of new energy sources such as the windmill, the fulling mill and the horse collar (which doubled the efficiency of horse-power).

The principality traded cattle, skins, cheese, timber, horses, wax, dogs, hawks, and fleeces, but also flannel (with the growth of fulling mills). Flannel was second only to cattle among the principality's exports. In exchange, the principality imported salt, wine, wheat, and other luxuries from London and Paris. But most importantly for the defence of the principality, iron and specialised weaponry were also imported. Welsh dependence on foreign imports was a tool that England used to wear down the principality during times of conflict between the two countries.

1284 to 1543: Annexation by the English crown

Establishment and governance

Between 1277 and 1283, Edward I of England conquered the territories of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd and the other last remaining native Welsh princes. The governance and constitutional position of the principality after its conquest was set out in the Statute of Rhuddlan of 1284. In the words of the statute, the principality was "annexed and united" to the English crown.

The principality's administration was overseen by the Prince of Wales's council comprising between 8 and 15 councillors sitting in London or, later, Ludlow in Shropshire. The council acted as the principality's final court of appeal. By 1476, the council, which became known as the Council of Wales and the Marches, began taking responsibility not only for the principality itself but its authority was extended over the whole of Wales.

The territory of the principality fell into two distinct areas: the lands under direct royal control and lands that Edward I had distributed by feudal grants.

For lands under royal control, the administration, under the Statute of Rhuddlan, was divided into two territories: North Wales based at Caernarfon and West Wales based at Carmarthen. The Statute organized the Principality into shire counties. Carmarthenshire and Cardiganshire were administered by the Justiciar of South Wales (or "of West Wales") at Carmarthen. In the North, the counties of Anglesey, Merionethshire, and Caernarfonshire were created under the control of Justiciar of North Wales and a provincial exchequer at Caernarfon, run by the Chamberlain of North Wales, who accounted for the revenues he collected to the Exchequer at Westminster. Under them were royal officials such as sheriffs, coroners, and bailiffs to collect taxes and administer justice. Another county, Flintshire, was created out of the lordships of Tegeingl, Hopedale and Maelor Saesneg, and was administered with the Palatinate of Cheshire by the Justiciar of Chester.

The remainder of the principality comprised lands that Edward I had granted to supporters shortly after the completion of the conquest in 1284, and which, in practice, became Marcher lordships: for example, the Lordship of Denbigh granted to the Earl of Lincoln and the Lordship of Powys granted to Owain ap Gruffydd ap Gwenwynwyn, who became Owen de la Pole. These lands after 1301 were held as tenants-in-chief of the Principality of Wales, rather than from the Crown directly, but were, for all practical purposes, not part of the principality.

Law

The Statute of Rhuddlan also introduced English common law to the principality, albeit with some local variation. Criminal law became entirely based on common law: the statute stated that "in thefts, larcenies, burnings, murders, manslaughters and manifest and notorious robberies – we will that they shall use the laws of England". However, Welsh law continued to be used in civil cases such as land inheritance, contracts, sureties, and similar matters, though with changes, for example, illegitimate sons could no longer claim part of the inheritance, which Welsh law had allowed them to do. In 1301, this modified principality was bestowed on the English monarch's heir apparent and thereafter became the territorial endowment of the heir to the throne.

There were few attempts by the English parliament to legislate in Wales and the lands of the principality remained subject to laws enacted by the king and his council. However, the king was prepared to allow Parliament to legislate in emergencies such as treason or rebellion. An example was the Penal Laws against Wales 1402 enacted to contain the Glyndŵr Rising and which, inter alia, prohibited the Welsh from intermarrying with the English or owning land in England or the Welsh boroughs. Some Welshman who were loyal to the Principality successfully petitioned for exemption from the penal laws. An example was Rhys ap Thomas ap Dafydd of Carmarthenshire who was a royal official in the southern part of the principality.

Castles, towns and colonisation

Edward's main concern following the conquest was to ensure the military security of his new territories and the stone castle was to be the primary means for achieving this. Under the supervision of James of Saint George, Edward's master-builder, a series of imposing castles was built, using a distinctive design and the most advanced defensive features of the day, to form a "ring of stone" around the northern part of the principality. Among the major buildings were the castles of Beaumaris, Caernarfon, Conwy and Harlech. Aside from their practical military role, the castles made a clear symbolic statement to the Welsh that the principality was subject to English rule on a permanent basis.