Redcliffe Caves

The Triassic red sandstone was dug into in the Middle Ages to provide sand for glass making and pottery production. Further excavation took place from the 17th to early 19th centuries and used for storage of trade goods. There is some evidence that prisoners captured during the French Revolutionary Wars or Napoleonic Wars were imprisoned in the caves but it is clear that the local folklore that slaves were imprisoned in the caves during the Bristol slave trade is false. After the closure of the last glass factory the caves were used for storage and became a rubbish dump. The caves are not generally open but have been used for film and music events.

The explored and mapped area covers over 1 acre (0.40 ha) however several areas are no longer accessible and the total extent of the caves is not known.

History

The caves were dug to provide sand for glass making and pottery production. They were dug into the Triassic red sandstone cliffs, which give the area its name, adjacent to the southern side of Bristol Harbour, behind Phoenix Wharf and Redcliffe Wharf. The first excavation was during the Middle Ages but the majority of the digging was during the mid 17th and early 19th centuries. In the larger caverns the stone columns supporting the roof were not sufficient and these have been supplemented with wall arches made of stone, brick and more recently of concrete.

In 1346 a hermit called John Sparkes lived in the caves and prayed for his benefactor Lord Thomas of Berkeley. Several other hermits lived in the caves between the 14th and 17th centuries.

There is no evidence to support the rumours that the caves were used to hold slaves during the Bristol slave trade of the 17th and 18th centuries, however they were used to store the goods brought in by ships from Africa and the West Indies. There is some evidence that prisoners captured during the French Revolutionary Wars or Napoleonic Wars were imprisoned in the caves, but there is no evidence to show they were involved in the creation of the New Cut.

Once the final glass factory in Bristol had closed the caves were used for storage and the disposal of rubbish. Some of the waste came from the Redcliffe Shot Tower at the corner of Redcliffe Hill and Redcliffe Parade, where the cellar was dug out into one of the tunnels. Waste from the lead shot production process was deposited between its opening in 1782 and closure in 1968.

During World War II small parts of the caves were surveyed for use as an air raid shelter. A bomb created a crater into the caves which was subsequently filled in blocking access to some parts of the cave system.

The caves have been used as an underground venue for the Bristol Film Festival, and for theatre productions.

Location and extent

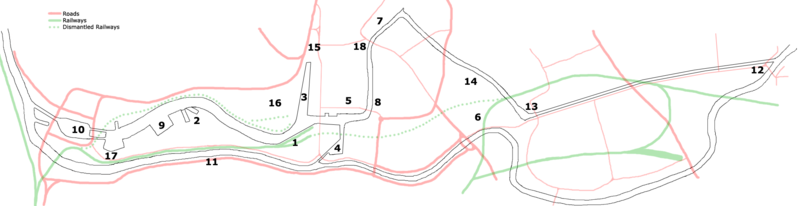

The full extent of the tunnels has not been explored as part of the site was split by a rail tunnel. The caves are believed to extend further than the currently visible area stretching to the south of the rail line. The explored and mapped area covers over 1 acre (0.40 ha) and extends nearly as a far as Bristol General Hospital. They may also once have linked with the crypt of St Mary Redcliffe. A survey in 1953 and 1954 explored and mapped the accessible portions and provided some evidence of the wider extent of the caves.

Several buildings in the area have or did have access to the caves from their cellars, including the Ostrich pub where part of a wall has been demolished to show part of one of the caves.

- Prince's Wharf, including M Shed, Pyronaut and Mayflower adjoining Prince Street Bridge

- Dry docks: SS Great Britain, the Matthew

- St Augustine's Reach, Pero's Bridge

- Bathurst Basin

- Queen Square

- Bristol Temple Meads railway station

- Castle Park

- Redcliffe Quay and Redcliffe Caves

- Baltic Wharf marina

- Cumberland Basin & Brunel Locks

- The New Cut

- Netham Lock, entrance to the Feeder Canal

- Totterdown Basin

- Temple Quay

- The Centre

- Canons Marsh, including Millennium Square and We The Curious

- Underfall Yard

- Bristol Bridge and Welsh Back

References

- ^ "Redcliffe Caves". Victoria County History. Archived from the original on 26 October 2016. Retrieved 2 June 2017.

- ^ "Redcliffe Caves the History". Redcliffe Caves. Archived from the original on 6 May 2016. Retrieved 2 June 2017.

- ^ "RIGS of the Month – September 2012. Recliffe Caves – Bristol". Avon RIGS Group. Archived from the original on 21 September 2015. Retrieved 2 June 2017.

- ^ Coules, Victoria (2006). Lost Bristol. Birlinn Limited. pp. 151–153. ISBN 9781841585338.

- ^ Mellor, Penny (2013). Inside Bristol: Twenty Years of Open Doors Day. Redcliffe Press. pp. 56–57. ISBN 978-1908326423.

- ^ Collins, S.J. (1954). "Surveying in Redcliffe Caves". Caving Report — Bristol Exploration Club. 1.

- ^ "Redcliffe Caves". Bristol Link. Archived from the original on 26 February 2017. Retrieved 2 June 2017.

- ^ "Redcliffe Caves". Sweet History. Archived from the original on 8 July 2016. Retrieved 2 June 2017.

- ^ Watson, Sally (2002). Secret Underground Bristol. Broadcast Books. pp. 20–26. ISBN 978-1874092957.

- ^ Efstathios, Tsolis (10 March 2007). "An Awkward thing" (PDF). University of Bristol. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 March 2015. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- ^ "Lead Working in Bristol". brisray.com. Archived from the original on 22 March 2015. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- ^ Mosse, John. "Redcliff Shot Tower" (PDF). Bristol Industrial Archaeological Society (BIAS). Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 March 2015. Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- ^ Duckeck, Jochen. "Redcliffe Caves". Show Caves. Archived from the original on 19 June 2016. Retrieved 2 June 2017.

- ^ "Redcliffe Sand Mines, Bristol". The Time Chamber. Archived from the original on 27 April 2016. Retrieved 2 June 2017.

- ^ "Underground Cinema Launches in Redcliffe Caves". Bristol Film Festival. Retrieved 2 June 2017.

- ^ Jones, Craig (13 March 2017). "Bristol Film Festival screen A Clockwork Orange in Redcliffe Caves". Bristol Post. Retrieved 2 June 2017.

- ^ "Macbeth at the Redcliffe Caves". Insane Root Theatre. Retrieved 2 June 2017.

- ^ "Redcliffe Caves". Nettleden. Archived from the original on 18 June 2016. Retrieved 2 June 2017.

- ^ "Historic site, The Ostrich pub, Bristol". Port Cities Bristol. Archived from the original on 12 January 2017. Retrieved 2 June 2017.

- ^ "Cave inside The Ostrich Pub, Bristol". Port Cities Bristol. Archived from the original on 12 January 2017. Retrieved 2 June 2017.

External links

![]() Media related to Redcliffe Caves at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Redcliffe Caves at Wikimedia Commons