Ringway 3

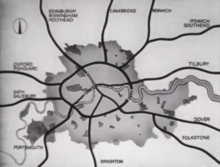

There had been plans to construct new roads around London to help traffic since at least the 17th century. Several were built in the early 20th century such as the North Circular Road, Western Avenue and Eastern Avenue, and further plans were put forward in 1937 with The Highway Development Survey, followed by the County of London Plan in 1943. The Ringways originated from these earlier plans, and consisted of the main four ring roads and other developments. Certain sections were upgrades of existing earlier projects such as the North Circular, but much of it was new-build. Construction began on some sections in the 1960s in response to increasing concern about car ownership and traffic.

The Ringway plans attracted vociferous opposition towards the end of the decade over the demolition of properties and noise pollution the roads would cause. Local newspapers published the intended routes, which caused an outcry among local residents living on or near them who would have their lives irreversibly disrupted. Following an increasing series of protests, the scheme was cancelled in 1973, at which point only three sections had been built. Some traffic routes originally planned for the Ringways were re-used for other road schemes in the 1980s and 1990s, most significantly the M25, which was created out of two different sections of Ringways joined together. The project caused an increase in road protesting and an eventual agreement that new road construction in London was not generally possible without huge disruption. Since 2000, Transport for London has promoted public transport and discouraged road use.

History

Background

London has been significantly congested since the 17th century. Various select committees were established in the late 1830s and early 1840s in order to establish means of improving communication and transport in the city. The Royal Commission on London Traffic (1903–05) produced eight volumes of reports on roads, railways and tramways in the London area, including a suggestion for "constructing a circular road about 75 miles in length at a radius of 12 miles from St Paul's".

Between 1913 and 1916, a series of conferences took place, bringing all road plans in Greater London together as a single body. Over the next decade, 214 miles (344 km) of new roads were constructed, primarily as post-war unemployment relief. These included the North Circular Road from Hanger Lane to Gants Hill, Western Avenue and Eastern Avenue, the Great West Road bypassing Brentford, and bypasses of Kingston, Croydon, Watford and Barnet. In 1924, the Ministry of Transport proposed another circular route, the North Orbital Road. This ran further out from London than the North Circular and was planned to be around 70 miles (110 km) long, running from the A4 at Colnbrook to the A13 at Tilbury.

The Highway Development Survey, 1937

In May 1938, Sir Charles Bressey and Sir Edwin Lutyens published a Ministry of Transport report, The Highway Development Survey, 1937, which reviewed London's road needs and recommended the construction of many miles of new roads and the improvement of junctions at key congestion points. Amongst their proposals was the provision of a series of orbital roads around the city with the outer ones built as American-style Parkways – wide, landscaped roads with limited access and grade-separated junctions. These included an eastern extension of Western Avenue, which eventually became the Westway.

Bressey's plans called for significant demolition of existing properties, that would have divided communities if they had been built. However, he reported that the average traffic speed on three of London's radial routes was 12.5 miles per hour (20.1 km/h), and consequently their construction was essential. The plans stalled, as the London County Council were responsible for roads in the capital, and could not find adequate funding.

County of London Plan and Greater London Plan, 1940s

The Ringway plan had developed from early schemes prior to the Second World War through Sir Patrick Abercrombie's County of London Plan, 1943 and Greater London Plan, 1944. One of the topics that Abercrombie's two plans had examined was London's traffic congestion, and The County of London Plan proposed a series of ring roads labelled A to E to help remove traffic from the central area.

Even in a war-ravaged city with large areas requiring reconstruction, the building of the two innermost rings, A and B, would have involved considerable demolition and upheaval. The cost of the construction works needed to upgrade the existing London streets and roads to dual carriageway or motorway standards was considered significant; the A ring would have displaced 5,300 families. Because of post-war funding shortages, Abercrombie's plans were not intended to be carried out immediately. They were intended to be gradually built over the next 30 years. The subsequent austerity period meant that very little of his plan was carried out. The A Ring was formally cancelled by Clement Attlee's Labour government in May 1950. After 1951, the County of London focused on improving existing roads rather than Abercrombie's proposals.

Ringway Scheme, 1960s

By the start of the 1960s, the number of private cars and commercial vehicles on the roads had increased considerably from the number before the war. British car manufacturing doubled between 1953 and 1960. The Conservative government, led by Prime Minister Harold Macmillan, had strong ties to the road transport industry, with more than 70 members of parliament being members of the British Road Federation. Political pressure to build roads and improve vehicular traffic increased, which led to a revival of Abercrombie's plans.

The Ringway plan took Abercrombie's earlier schemes as a starting point and reused many of his proposals in the outlying areas but scrapped the plans in the inner zone. Abercrombie's A Ring was scrapped as being far too expensive and impractical. The innermost circuit, Ringway 1, was approximately the same distance from the centre as the B Ring. It used some of Abercrombie's suggested route, but it was planned to use existing transport corridors, such as railway lines, much more than before. The location of these lines produced a ring that was distinctly box-shaped, and Ringway 1 was unofficially called the London Motorway Box.

In 1963, Colin Buchanan published a report, Traffic in Towns, which had been commissioned by the Transport Minister, Ernest Marples. In contrast to earlier reports, it cautioned that road building would generate and increase traffic and cause environmental damage. It also recommended pedestrianisation of town centres and segregating different traffic types. The report was published by Penguin Books and sold 18,000 copies. Several key ideas in the report would later be perceived as being correct as road protesting grew from the 1980s onward. The London Traffic Survey was published the following year, and concluded that the Ringways should be built in order to cater for future network traffic, instead of Traffic in Towns which said if a road was not built, there would be no demand along that route anyway. The 1960s plans were developed over a period of several years and were subject to a continuing process of review and modification. Roads were added and omitted as the overall scheme was altered, and many alternative route alignments were considered during the planning process The plan was published in stages starting with Ringway 1 in 1966 and Ringway 2 in 1967. After the Conservatives won the GLC elections in the latter year, they confirmed that both Ringways would be constructed as planned.

The plan was hugely ambitious, and almost immediately attracted opposition from several directions. Ringway 1 was designed to be an eight-lane elevated motorway running through the middle of many town centres such as Camden Town, Brixton and Dalston. A principal problem was the route of Ringway 2 in south London, given that the South Circular Road was largely an unimproved series of urban streets and there were fewer railway lines to follow. Parts would be built with four lanes in each direction, and in some cases there was no other plan than to destroy whatever urban streets were in the way of the new road. At Blackheath, the road would have run in a deep-bored tunnel to avoid any impact on the local area, at an estimated cost of £38 million. However, until around 1967, the opposition was more towards specific proposals instead of the concept of Ringways generally.

The report Motorways in London, published in 1969 by the architect/planner Lord Esher and Michael Thomson, a transport economist at the London School of Economics, calculated that costs had been enormously underestimated and would show marginal economic returns. They predicted large quantities of additional traffic that would be generated purely as a result of the new roads. Access to the new roads would soon be overwhelmed even before the rings and radial roads were near capacity, while about 1 million Londoners would find their lives blighted by living within 200 yards of a motorway. Reports suggested between 15,000 and 80,000 Londoners would lose their homes as a result of the Ringways. The Treasury and the Ministry of Transport both came out against the scheme, primarily because of worries over the cost. The Chancellor of the Exchequer Roy Jenkins said he could not prevent the GLC from proposing the schemes, but assumed that the government could ultimately prevent them from being implemented.

Despite this opposition, the GLC continued to develop its plans, and began the construction of some of the parts of the scheme. The plan, still with much of the detail to be worked out, was included in the Greater London Development Plan, 1969 (GLDP) along with much else not related to roads and traffic management. In 1970, the GLC estimated that the cost of building Ringway 1 along with sections of 2 and 3 would be £1.7 billion (approximately £33.2 billion as of 2023).

In 1970, the British Road Federation surveyed 2,000 Londoners, 80% of whom favoured more new roads being built. In contrast, a public enquiry was held to review the GLDP in a climate of strong and vocal opposition from many of the London Borough councils and residents associations that would have seen motorways driven through their neighbourhoods. The Westway and a section of the West Cross Route from Shepherd's Bush to North Kensington, opened in 1970. It showed the public what the Ringways would be like for local residents and what demolition would be required, and led to increased complaints over the scheme. The GLDP received 22,000 formal objections by 1972. The GLC realised that the South Cross Route might be impractical to build, and looked instead at integrating public transport through a new park-and-ride scheme at Lewisham that would serve a new Fleet line on the London Underground.

The GLC attempted to hold on to the Ringway plans until the early 1970s, hoping that they would eventually be built. By 1972, in an attempt to placate the Ringway plan's vociferous opponents, the GLC removed the northern section of Ringway 1 and the southern section of Ringway 2 from the proposals. In January 1973, the enquiry recommended that Ringway 1 be built, but that much of the rest of the Ringway schemes be abandoned. The project was submitted to the Conservative government for approval and, for a short period, it appeared that the GLC had made enough concessions for the scheme to proceed. A report around this time commissioned by planning lawyer Frank Layfield showed that the GLDP was too dependent on roads for its transport plans. Because the GLC had proposed the Ringways as a complete scheme, protesters against specific parts of it in different areas were able to unite against a common goal, which led to the Layfield Inquiry successfully challenging the proposals.

The Labour party made large gains in the GLC elections of April 1973 with a policy of fighting the Ringways scheme. Given the continuing fierce opposition across London and the likely enormous cost, the cabinet cancelled funding and hence the project.

Ringway 1

Ringway 1 was the London Motorway box, comprising the North, East, South and West Cross Routes. Ringway 1 was planned to comprise four sections across the capital forming a roughly rectangular box of motorways. These sections were designated:

- North Cross Route – from Harlesden to Hackney Wick via West Hampstead, Camden Town, Highbury and Dalston

- East Cross Route – from Hackney Wick to Kidbrooke via Bow, Blackwall and Greenwich

- South Cross Route – from Kidbrooke to Battersea via Lewisham, Peckham, Brixton and Clapham

- West Cross Route – from Battersea to Harlesden via Sands End, Earl's Court, West Kensington, Shepherd's Bush and North Kensington

Much of the scheme would have been constructed as elevated roads on concrete pylons and the routes were designed to follow the alignments of existing railway lines to minimise the amount of land required for construction, including the North London line in the north, the Greenwich Park branch line in the south, and the West London line to the west.

Ringway 1 was expected to cost £480 million (£9.38 billion today) including £144 million (£2.74 billion today) for property purchases. It would require 1,048 acres (4.24 km) and affect 7,585 houses.

Only two parts of Ringway 1 were completed and opened to traffic. Part of the West Cross Route between North Kensington and Shepherd's Bush was opened by John Peyton and Michael Heseltine in 1970, simultaneously with Westway, to protests; some residents hung a huge banners with 'Get us out of this Hell – Rehouse Us Now' outside their windows and protesters disrupted the opening procession by driving a lorry the wrong way along the new road. The East Cross Route, incorporating the new 'eastern bore' of the Blackwall Tunnel opened in 1967, was completed in 1979.