Royal Mausoleum (Mauna ʻAla)

Background

In the early 19th century, the area near an ancient burial site was known as Pohukaina. It is believed to be the name of a chief (sometimes spelled Pahukaina) who according to legend chose a cave in Kanehoalani in the Koʻolau Range for his resting place. The land belonged to Kekauluohi, who later ruled as Kuhina Nui, as part of her birthright.

After 1825, the first Western-style royal tomb was constructed for the bodies of King Kamehameha II and his queen Kamāmalu near the current ʻIolani Palace. They were buried on August 23, 1825. The idea was heavily influenced by the tombs at Westminster Abbey during Kamehameha II's trip to London. The mausoleum was a small house made of coral blocks with a thatched roof. It had no windows, and it was the duty of two chiefs to guard the iron-locked koa door day and night. No one was allowed to enter the vault except for burials or Memorial Day, a Hawaiian holiday celebrated on December 30. Over time, as more bodies were added, the small vault became crowded, so other chiefs and retainers were buried in unmarked graves nearby. In 1865 a selected eighteen coffins were removed to the Royal Mausoleum named Mauna ʻAla in Nuʻuanu Valley. But many chiefs remain on the site including: Keaweʻīkekahialiʻiokamoku, Kalaniʻōpuʻu, Chiefess Kapiʻolani, and Haʻalilio.

Prior to the 19th century, the remains of aliʻi of Hawaiʻi island were buried at Hale o Keawe and Hale o Līloa. Other Western-style tombs include a burial site at Honolulu Fort which was lost when the fort was demolished in 1857, a tomb in Lahaina located near Halekamani, and a tomb on the island of Mokuʻula in Lahaina. The royal remains from the last two burial sites were transferred to the cemetery of Waiola Church in 1884.

Construction

The 2.75-acre (11,000 m) mausoleum was designed by architect Theodore Heuck. By 1862, the Royal Tomb at Pohukaina was full and there were no space for the coffins of Prince Albert, who died August 27, 1862, and King Kamehameha IV, who died November 30, 1863. Kamehameha IV's funeral was delayed for three months while a new mausoleum was built.

Immediately Kamehameha V, brother of Kamehameha IV, started construction of a new mausoleum building in the Nuʻuanu Valley on a site chosen by Kamehameha IV and his wife Queen Emma. The Right Reverend Thomas Nettleship Staley, first Anglican Bishop of Honolulu (1823–1898), oversaw construction. The west (ʻEwa) wing was completed at the end of January 1864. A large funeral procession February 3, 1864, brought the body of Kamehameha IV from ʻIolani Palace. His casket was placed on a stand in the new wing. Later in the evening, bearers brought the casket of Ka Haku o Hawaiʻi (as Prince Albert was known) and laid him to rest alongside his father. Queen Emma was so overcome with grief that she camped on the grounds of Mauna ʻAla, and slept in the mausoleum.

The mausoleum was completed in 1865, adjacent to the public 1844 Oahu Cemetery. The mausoleum seemed a fitting place to bury other past monarchs of the Kingdom of Hawaii and their families. The remains of past deceased royals were transferred in a torchlit ceremony at night leading from Pohukaina to the Nuʻuanu Valley on October 30, 1865.

Robert Crichton Wyllie, Minister of Foreign Affairs, was buried here in October 1865. Over time, the remains of almost all of Hawaii's monarchs, their consorts, and various princes and princesses would rest at the Royal Mausoleum.

Kamehameha I and William Charles Lunalilo are the only two kings not resting at the mausoleum. William Charles Lunalilo, the shortest-reigning Hawaiian monarch, (one year and 25 days only), was buried in the Lunalilo Tomb in the church cemetery resting in the courtyard of Kawaiahaʻo Church. Princess Nāhiʻenaʻena and Queen Keōpūolani are buried on Maui at Waiola Church.

Kamehameha I's remains were hidden in a traditional practice to preserve the mana (power) of the aliʻi at the time of the Hawaiian religion. For several generations, descendants of Hoʻolulu, one of the few chosen to help bury the remains of Kamehameha, have been appointed as caretakers.

Additional modifications

On November 9, 1887, after the main mausoleum building became too crowded, the caskets belonging to members of the Kamehameha Dynasty were moved to the newly built Kamehameha Tomb, an underground vault commissioned by Charles Reed Bishop, husband of Bernice Pauahi Bishop. The Territory of Hawaii built a second underground crypt, the Wyllie Tomb (formerly known as the Queen Emma Tomb) in 1904 to separate the caskets of Robert Crichton Wyllie and the relatives of Queen Emma. In 1907, the Territory of Hawaii allocated $20,000 for the construction of a separate underground vault for the Kalākaua family. Queen Liliʻuokalani and Prince Jonah Kūhiō Kalanianaʻole were consulted in the construction process. On June 24, 1910, the caskets from the Kalākaua family were moved to newly construct Kalākaua Crypt in a torchlit nighttime ceremony supervised by the former queen.

In 1922 the main building was converted to a chapel after the last royal remains were moved to tombs constructed on the grounds. The chapel was added to the National Register of Historic Places August 7, 1972.

In 2023, Abigail Kinoiki Kekaulike Kawānanakoa (1926–2022) became the most recent person to be buried in the Royal Mausoleum. Prior to her death there had not been a burial at the Royal Mausoleum since David Kalākaua Kawānanakoa in 1953. A new tomb was constructed since the Kalākaua vault was at capacity.

Legal Status

Mauna ʻAla was removed from the public lands of the United States by a joint resolution of Congress in 1900, two years after the annexation in 1898 of Hawaii by the Newlands Resolution and President William McKinley.

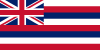

The Mausoleum is one of the only places in Hawaii where the flag of Hawaii can officially fly alone without the American flag. The other three places are Iolani Palace, the Puʻuhonua o Hōnaunau Heiau and Thomas Square.

Kahu of the Royal Mausoleum

These are the keepers or kahu of the Royal Mausoleum at Mauna Ala:

- Nahalau, till 1873

- Joseph Keaoa, from July 10, 1873

- Haumea, from May 3, 1878

- Pius F. Koakanu, until March, 1885

- Lanihau, from March 6, 1885

- Keano, from July 31, 1886

- Naholowaʻa, from September 17, 1888

- Poʻomaikelani (1839–1895), from October 15, 1888

- Wiliokai (mentioned in Queen Liliʻuokalani's diary entry), until March 24, 1893

- Maria Angela Kahaʻawelani Beckley Kahea (1847–1909), from March 24, 1893, to July 11, 1909

- David Kaipeʻelua Kahea (1845–1921), from March 24, 1893, to 1915 (jointly with wife)

- Frederick Malulani Beckley Kahea (1882–1949), from 1915 to 1947

- William Edward Bishop Kaiheʻekai Taylor (1882–1956), from 1947 to 1956

- Emily Kekahaloa Namauʻu Taylor, from 1956 to 1961

- ʻIolani Luahine, from 1961 to 1965

- Lydia Namahanaikaleleokalani Taylor Maiʻoho, from 1966 to 1994

- William "Bill" John Kaiheʻekai Maiʻoho, from 1995 to 2015

- William Bishop Kaiheʻekai "Kai" Maiʻoho, from 2015 to May 1, 2023

See also

- List of burials at the Royal Mausoleum of Hawaii

- Thomas Nettleship Staley First Anglican Bishop of Honolulu

References

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- ^ Kaiheʻekai Maiʻoho, William John (2003). "Nuʻuanu, Oʻahu – Memories: Mauna ʻAla". Pacific Worlds & Associates. Retrieved December 8, 2009.

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Pohukaina

- ^ Papers of the Hawaiian Historical Society. Bulletin Publishing Company. 1930. p. 34.

- ^ The Friends of ʻIolani Palace (2001). "Ka Pa Aliʻi: Protecting This Sacred Place: September 8, 2001 – Old Archives Building".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Jim Bartels (2003). "Pohukaina". Pacific Worlds web site. Retrieved April 7, 2010.

- ^ "Ka Hoihoi Ia Ana O Na Kino Kupapau O Na Alii I Make Mua Ma Ka Ilina Hou O Na Alii". Ka Nupepa Kuokoa. Vol. IV, no. 44. November 4, 1865. p. 2. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ Kam 2017, pp. 181–183.

- ^ Parker 2008, pp. 45–49.

- ^ Kam 2017, pp. 177–180.

- ^ Kam 2017, pp. 184–186.

- ^ Kam 2017, pp. 183–187.

- ^ Parker 2008, pp. 9–11.

- ^ Riconda, Dorothy (November 15, 1971). "The Royal Mausoleum nomination form". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. Retrieved October 13, 2009.

- ^ Parker 2008, pp. 19–49.

- ^ Parker 2008, p. 11.

- ^ Kam 2017, p. 180.

- ^ Apgar, Sally (March 5, 2006). "Mai'ohos feel drawn to royal burial site Six generations have cared for the Nuuanu mausoleum for Hawaii's kings". Honolulu Star-Bulletin.

- ^ Parker 2008, p. 13.

- ^ Kam 2017, pp. 187–190.

- ^ Kam 2017, pp. 190–192.

- ^ Parker 2008, p. 14.

- ^ Kam 2017, pp. 192–196.

- ^ Thrum, Thomas G. (1911). "New Kalakaua Dynasty Tomb". All about Hawaii: The recognized book of authentic information on Hawaii. Honolulu Star-Bulletin.

- ^ Fawcett, Denby (January 17, 2023). "Is The Funeral Of Abigail Kawananakoa The Last Hawaiian Royal Burial?". Honolulu Civil Beat. Honolulu. Retrieved January 21, 2023.

- ^ David, Mari-Ela (July 22, 2009). "The Royal Mausoleum, the sacred resting place of Hawaii's Alii". KHNL News. Retrieved December 22, 2014.

- ^ Clark, John (2019). "The Kamehameha III Statue in Thomas Square". The Hawaiian Journal of History. 53. Honolulu: Hawaiian Historical Society: 147–149. doi:10.1353/hjh.2019.0008. ISSN 2169-7639. OCLC 60626541. S2CID 214511964.

- ^ Fuller, Landry (August 2, 2016). "Flying high". West Hawaii Today. Kailua-Kona: Oahu Publications, Inc. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- ^ Parker 2008, p. 55.

- ^ Apgar, Sally (March 5, 2006). "Mai'ohos feel drawn to royal burial site – Six generations have cared for the Nuuanu mausoleum for Hawaii's kings". Honolulu Star Bulletin. Retrieved June 5, 2014.

- ^ Kaeo & Queen Emma 1976, p. 14.

- ^ "Na Nu Hou Hawaii". Ko Hawaii Paeaina. Vol. VIII, no. 10. Honolulu. March 7, 1885. p. 2.

- ^ "Lanihau (w) office record". state archives digital collections. state of Hawaii. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved June 17, 2014.

- ^ Liliʻuokalani (March 25, 1893). "Saturday, March 25, 1893". Diary entry of Liliʻuokalani. Hawaii State Archives. Call Number: M93, Liliʻuokalani Diary 1893.

- ^ "Former Caretaker Of Royal Mausoleum Dies On Birthday". The Honolulu Advertiser. Honolulu. October 28, 1921. p. 12. Retrieved February 1, 2020.

- ^ "Hawaii's Royal Mausoleum curator dies". Honolulu Star Advertiser. February 11, 2015. Retrieved May 9, 2015.

- ^ Star-Advertiser staff (October 22, 2015). "New curator serving at Oahu's royal mausoleum". staradvertiser.com. Honolulu Star Advertiser. Retrieved December 14, 2015.

Bibliography

- Kaeo, Peter; Queen Emma (1976). Korn, Alfons L. (ed.). News from Molokai, Letters Between Peter Kaeo & Queen Emma, 1873–1876. Honolulu: The University Press of Hawaii. hdl:10125/39980. ISBN 978-0-8248-0399-5. OCLC 2225064.

- Kam, Ralph Thomas (2017). Death Rites and Hawaiian Royalty: Funerary Practices in the Kamehameha and Kalakaua Dynasties, 1819–1953. S. I.: McFarland, Incorporated, Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4766-6846-8. OCLC 966566652.

- Parker, David "Kawika" (2008). "Crypts of the Ali`i The Last Refuge of the Hawaiian Royalty". Tales of Our Hawaiʻi (PDF). Honolulu: Alu Like, Inc. OCLC 309392477. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 11, 2013.

External links

- Interactive Map

- D. Thor Minnick (2002). "Mauna'ala:The Royal Mausoleum, Nu'uanu Valley, Oahu, Hawai'i". Minnick Associates. Retrieved October 13, 2009.

- Royal Mausoleum at Find a Grave

- Mauna ʻAla, Royal Mausoleum of Hawaii Photo Gallery

- Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) No. HI-23, "Royal Mausoleum, 2261 Nuuanu Avenue, Honolulu, Honolulu County, HI", 4 photos, 7 data pages, 1 photo caption page

- Royal Mausoleum State Monument