São Paulo (state)

With more than 44 million inhabitants in 2022, São Paulo is the most populous Brazilian state (around 22% of the Brazilian population), the world's 28th-most-populous sub-national entity and the most populous sub-national entity in the Americas, and the fourth-most-populous political entity of South America, surpassed only by the rest of the Brazilian federation, Colombia, and Argentina. The local population is one of the most diverse in the country and descended mostly from Italians, who began immigrating to the country in the late 19th century; the Portuguese, who colonized Brazil and installed the first European settlements in the region; Indigenous peoples, many distinct ethnic groups; Africans, who were brought from Africa as enslaved people in the colonial era and migrants from other regions of the country. In addition, Arabs, Armenians, Chinese, Germans, Greeks, Japanese, Spanish and American Southerners also are present in the ethnic composition of the local population.

Today's area corresponds to the state territory inhabited by Indigenous peoples from approximately 12,000 BC. In the early 16th century, the coast of the region was visited by Portuguese and Spanish explorers and navigators. In 1532 Martim Afonso de Sousa would establish the first Portuguese permanent settlement in the Americas—the village of São Vicente, in the Baixada Santista. In the 17th century, the paulistas bandeirantes intensified the exploration of the colony's interior, which eventually expanded the territorial domain of Portugal and the Portuguese Empire in South America. In the 18th century, after the establishment of the province of São Paulo, the region began to gain political weight. After independence in 1822, São Paulo began to become a major agricultural producer (mainly coffee) in the newly constituted Empire of Brazil, which ultimately created a rich regional rural oligarchy, which would switch on the command of the Brazilian government with Minas Gerais's elites during the early republican period in the 1890s. Under the Vargas Era, the state was one of the first to initiate a process of industrialization and its population became one of the most urban of the federation.

São Paulo's economy is very strong and diversified, having the largest industrial, scientific and technological production in the country — being the largest national research and development hub and home to the best universities and institutes —, the world's largest production of orange juice, sugar and ethanol, and the highest GDP among all Brazilian states, being the only one to exceed the one-trillion-real range. In 2020, São Paulo's economy accounted for around 31.2% of the total wealth produced in the country — which made the state known as the "locomotive of Brazil" — and this is reflected in its cities, many of which are among the richest and most developed in the country. São Paulo alone is wealthier than Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay and Bolivia combined, with a GDP of 2.7 trillion reais (603.4 billion dollars); therefore, if it were a sovereign country, its nominal GDP would be the 21st largest in the world (2020 estimate). In addition to the economy, São Paulo is acknowledged as a major Brazilian tourist destination by national and international tourists due to its natural beauty, historical and cultural heritage —it has multiple sites inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List—, inland resorts, climate and great vocation for the service, business, entertainment, fashion sectors, culture, leisure, health, education, and many others. It has high social indices compared to those recorded in the rest of the country, such as the second-highest Human Development Index (HDI), the fourth GRDP per capita, the second-lowest infant mortality rate, the third-highest life expectancy, the lowest homicide rate, and the third-lowest rate of illiteracy among the federative units of Brazil.

History

Early period

The region of the current state of São Paulo was already inhabited by Amerindian peoples since at least approximately 10,000 BCE, as evidenced by studies carried out in ancient archaeological sites (such as the sites Caetetuba, Bastos, Boa Esperança II and Lagoa do Camargo) in different parts of the current territory of São Paulo. There are even records (e.g. - studies at the Rincão I archaeological site) that suggest that ancient human occupation was already present in São Paulo 17 thousand years ago, during the last glacial maximum. There are also several archaeological sites (such as Caetetuba, Alice Boer and Rincão I) in the central portion of the state that share similar patterns of working rocks into stone points and plano-convex artifacts similar to each other, so that they are seen as members of the same ancient ancestral culture, linked to the Rioclarense lithic industry. These ancient human groups were hunter-gatherers, living as nomads and semi-nomads in the current territory of São Paulo, living directly from what they could obtain from the local land.

In pre-European times, the area that is now São Paulo state was occupied by the Tupi people's nation, who subsisted through hunting and cultivation. The first European to settle in the area was João Ramalho, a Portuguese sailor who may have been shipwrecked around 1510, ten years after the first Portuguese landfall in Brazil. He married the daughter of a local chieftain and became a settler. In 1532, the first colonial expedition, led by Martim Afonso de Sousa of Portugal, landed at São Vicente (near the present-day port at Santos). De Sousa added Ramalho's settlement to his colony.

Early European colonization of Brazil was very limited. Portugal was more interested in Africa and Asia. But with English and French raiding privateer ships just off the coast, the territory had to be protected. Unwilling to shoulder the naval defense burden himself, the Portuguese ruler, King Joao III, divided the coast into "captaincies", or swathes of land, 50 leagues apart. He distributed them among well-connected Portuguese, hoping that each would be self-reliant. The early port and sugar-cultivating settlement of São Vicente was one rare success connected to this policy. In 1548, João III brought Brazil under direct royal control.

Fearing Indian attack, he discouraged development of the territory's vast interior. Some whites headed nonetheless for Piratininga, a plateau near São Vicente, drawn by its navigable rivers and agricultural potential. Borda do Campo, the plateau settlement, became an official town (Santo André da Borda do Campo) in 1553. The history of São Paulo city proper begins with the founding of a Jesuit mission of the Roman Catholic order of clergy on 25 January 1554—the anniversary of Saint Paul's conversion. The station, which is at the heart of the current city, was named São Paulo dos Campos de Piratininga (or just Pateo do Colégio). In 1560, the threat of Indian attack led many to flee from the exposed Santo André da Borda do Campo to the walled fortified Colegio. Two years later, the Colégio was besieged. Though the town survived, fighting took place sporadically for another three decades.

By 1600, the town had about 1,500 citizens and 150 households. Little was produced for export, save a number of agricultural goods. The isolation was to continue for many years, as the development of Brazil centered on the sugar plantations in the north-east.

The city's location, at the mouth of the Tietê-Paranapanema river system (which winds into the interior), made it an ideal base for another activity—enslaving expeditions. The economics were simple. Enslaved manpower for Brazil's northern sugar plantations were in short supply. Enslaved Africans were expensive, so demand for indigenous captives soared. The task was, nonetheless, hard, if not impossible, to achieve.

Expansion

Among those who attempted to enslave the native were explorers of the hinterland called "bandeirantes". From their base in São Paulo, they also combed the interior in search of natural riches. Silver, gold and diamonds were companion pursuits, as well as the exploration of unknown territories. Roman Catholic missionaries sometimes tagged along, as efforts at converting the natives aborigines (Indians) worked hand in hand with Portuguese colonialism.

Despite their atrocities, the wild and hardy bandeirantes are now equally remembered for penetrating Brazil's vast interior. Trading posts established by them became permanent settlements. Interior routes opened up. Though the bandeirantes had no loyalty to the Portuguese crown, they did claim land for the king. Thus, the borders of Brazil were pushed forward to the northwest and the Amazon region and west to the Andes Mountains.

French Emperor Napoleon's invasion of Portugal in 1807 prompted the British with their vast powerful Royal Navy to evacuate King João VI of Portugal, Portugal's prince regent, from the capital Lisbon, across the Atlantic to Rio de Janeiro and Brazil then became the first overseas colony to become the temporary headquarters of the Portuguese Empire. João VI rewarded his hosts with economic reforms that would prove crucial to São Paulo's rise. Brazil's ports—long closed to non-Portuguese ships—were opened up to international trade. Restrictions on domestic manufacturing were waived.

When Napoleon was defeated in 1815, with the end of the Napoleonic Wars, João gave political shape to his territory, which soon became the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves. Portugal and Brazil, in other words, were ostensibly co-equals. Returning to Portugal six years later, João left his son, Pedro, to rule as regent and governor.

Empire of Brazil period

Pedro I of Brazil inherited his father's love of Brazil, resisting demands from Lisbon that Brazil should be ruled from Europe once again. Legend has it that in 1822 the regent was riding outside São Paulo when a messenger delivered a missive demanding his return to Europe, and Dom Pedro waved his sword and shouted "Independência ou morte!" (Independence or death).

João had whetted the appetite of Brazilians, who now sought a full break from the monarchy. The ever-restless Paulistas were at the vanguard of the independence movement. The small mother country of Portugal was in no position to resist—on 7 September 1822, Dom Pedro rubber-stamped Brazil's independence. He was crowned emperor shortly afterwards. The emperors ruled an independent Brazil until 1889. Over this time, the growth of liberalism in Europe had a parallel in Brazil. As the Brazilian provinces became more assertive, São Paulo was the scene of a minor (and unsuccessful) liberal revolution in 1842. When independence was declared, the city of São Paulo had just 25,000 people and 4,000 houses, but the next 60 years would see gradual growth. In 1828, the Law School, the pioneer of the city's intellectual tradition, opened. The first newspaper, O Farol Paulistano, appeared in 1827. Municipal developments such as botanical gardens, an opera house and a library, gave the city a cultural boost.

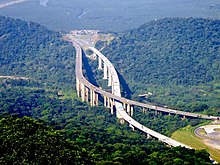

Regardless, São Paulo still faced many hurdles, especially transport. Mule-trains were the main method of transportation, and the road from the plateau down to the port of Santos was famously arduous. In the late 1860s São Paulo got its first railway line, developed by British engineers, to the Port of Santos. Other lines, such as a railway to Campinas, were soon built. This was good timing, because in the 1880s the coffee craze hit in earnest. Brazil, which had been growing it since the mid-18th century, could grow more. The Paraíba valley, which spans the states of Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, had suitable soil and climate. São Paulo city, at the western end of the Paraíba valley, was well positioned to channel the coffee to the port of Santos.

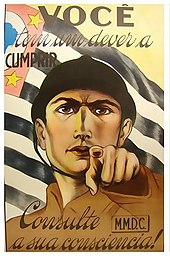

Republican era

Meanwhile, the Brazilian monarchy had fallen in 1889. A feudalistic regime, the new republic had friends only among the sugar planters of the Northeast, whose dominance Paulistanos, among others, despised. In 1891, a new federal constitution, which delegated power to the states, was approved. The new coffee elite saw its chance. São Paulo ironed out a power-sharing understanding—known as the "café com leite" (coffee-and-milk) deal—with dairy-rich Minas Gerais, Brazil's other dominant state. Together, they held a virtual lock on federal power. Brazilian politics now became a favourite pastime of the once-rebellious Paulistanos, who sent several presidents to Rio de Janeiro—including Prudente de Morais, Brazil's first civilian president, who took office in 1894.

Plantation labor was needed—this time for coffee, not sugar. Slavery had been fading since the import of enslaved Africans was outlawed in 1850. São Paulo, thanks to such figures as Luiz Gama (a former slave), was a center of abolitionism. In 1888, Brazil abolished slavery (it was the last country in the Americas to do so) and the freed African-Brazilians who had been helping build the nation were then forced to beg for their jobs back, working for food and shelter only because of the failure of the system to integrate them as equal citizens with Euro-Brazilians. In an effort to "bleach the race", as the nation's leaders feared Brazil was becoming a "black country", Spanish, Portuguese and Italian nationals were given incentives to become farm workers in São Paulo. The state government was so eager to bring in European immigrants that it paid for their trips and provided varying levels of subsidy.

By 1893, foreigners made up over 55 percent of São Paulo's population. Fearing oversupply, the government applied the brakes briefly in 1899; then the boom resumed. From 1908, the Japanese arrived in great numbers, many destined for the plantations on fixed-term contracts. By 1920, São Paulo was Brazil's second-largest city; a half-century before, it had been just the tenth-largest. Immigration and migration of Paulistas from other towns as well as Nordestinos and citizens from other states, the coffee industry, and modernization through the manufacturing of textiles, car and airplane parts, as well as food and technological industries, construction, fashion, and services transformed the greater São Paulo area into a thriving megalopolis and one of the world's greatest multiethnic regions.

Early 20th century

Between 1901 and 1910, coffee made up 51 percent of Brazil's total exports, far overshadowing rubber, sugar and cotton. But reliance on coffee made Brazil (and São Paulo in particular) vulnerable to poor harvests and the whims of world markets. The development of plantations in the 1890s, and widespread reliance on credit, took place against fluctuating prices and supply levels, culminating in saturation of the international market around the start of the 20th century. The government's policies of "valorisation "—borrowing money to buy coffee and stockpiling it, in order to have a surplus during bad harvests, and meanwhile taxing coffee exports to pay off loans—seemed feasible in the short term (as did its manipulation of foreign-exchange rates to the advantage of coffee growers). But in the longer term, these actions contributed to oversupply and eventual collapse.

São Paulo's industrial development, from 1889 into the 1940s, was gradual and inward looking. Initially, industry was closely associated with agriculture: cotton plantations led to the growth of textile manufacturing. Coffee planters were among the early industrial investors.