Saint-Amand Abbey

History

The abbey was founded around 633-639 in what was once a great tract of uninhabited land in the Vicoigne Forest between the Scarpe and the brook called the Elnon, from which the monastery took its first name, Elnon or Elnone Abbey. The founder was Saint Amand of Maastricht, under the patronage of Dagobert I. The name of the saint eventually became applied both to the abbey and the village that grew up round it. The abbot from about 652 was Jonatus.

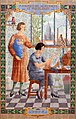

Apart from its considerable effect on the landscape, the abbey became a major centre of study during the Carolingian Renaissance. Notable members of the community included the 9th-century writer Milo of Saint-Amand, author of a metrical dictionary of Latin long and short syllables as well as a Life of Saint Amand, and his nephew, Hucbald of Saint-Amand, a noted music theorist and composer.

The abbey was totally destroyed by the Normans at the end of the 9th century. It was devastated by fire in 1066 and, thanks to generous benefactors, was rebuilt and became the richest abbey in the region. The abbey not completely restored until the 17th century, to an ambitious and much-admired plan implemented by Abbot Nicolas du Bois. In 1616-1617 Peter Paul Rubens painted a new high altarpiece for the monastery church, the Saint Stephen Triptych.

In 1672, Dom Mabillon discovered that, at the end of a manuscript of works of Gregory Nazianzen, there is a praise poem of the late 9th century in Old German, the Ludwigslied, which commemorates the victory of the Frankish army of Louis III over the Vikings on 3 August 881 at the Battle of Saucourt-en-Vimeu. The same manuscript, now held at the municipal library of Valenciennes, was found to contain one of the earliest literary texts in vernacular French, the poem called Sequence of Saint Eulalia. The Annales sancti Amandi, a set of annals of the Frankish kingdom, also originate from Saint-Amand.

The abbey was declared national property in 1789, and mostly demolished between 1797 and 1820. The former courthouse (échevinage) and the exuberantly decorated church tower, which now accommodates a faience museum, survive and can still be visited.

References

- ^ de Smet, J J (1861). Leven van den heiligen Amandus, aposter der Vlaenderens. Gent. pp. 93–95.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Butler, Alban (1866). The Lives of the Fathers, Martyrs, and Other Principal Saints, Volume 2. Dublin. p. 68.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ both the monastery and the village were also sometimes known as Elnone-en-Pévèle

- ^ Basil Watkins (2016), The Book of Saints: A Comprehensive Biographical Dictionary (8th rev. ed.), Bloomsbury, p. 386, s.v. "Jonatus".

- ^ Gasparov, Mikhail (1996). A History of European Versification. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 89. ISBN 0-19-815879-3.

- ^ Grasso 2019, p. 9.

- ^ Sauerlander, Willibald. The Catholic Rubens: Saints and Martyrs, Getty Publications, 2014, p. 177 ISBN 9781606062685

- ^ Green, Dennis H. (2002). "The "Ludwigslied" and the Battle of Saucourt". In Jesch, Judith (ed.). The Scandinavians from the Vendel period to the tenth century. Cambridge: Boydell. pp. 281–302. ISBN 9780851158679.

- ^ Base Mérimée: Ancienne église abbatiale, Ministère français de la Culture. (in French)

Sources

- Grasso, Maria R. (2019). Illuminating Society: The Body, Soul and Glorification of Saint Amand in the Miniature Cycle in Valenciennes, Bibliothèque Municipale, MS 500. Brill.

External links

- Nordmag.fr: Saint-Amand (in French)

- Universalis.fr: Saint-Amand, Abbaye de (in French)

- Saint-Amand-les-Eaux municipal website: Tour abbatiale (with pictures) (in French)