Solar Power In Turkey

Although similarly sunny, by 2021 Turkey had installed far less solar power than Spain. Solar power subsidizes coal and fossil gas power. Every gigawatt of solar power installed would save over US$100 million on gas import costs, and more of the country's electricity might be exported.

Most new solar power is tendered as part of hybrid power plants. Building new solar power plants would be cheaper than running existing import-dependent coal plants if they were not subsidized. However, think tank Ember has listed several obstacles to building utility-scale solar plants, such as insufficient new grid capacity for solar power at transformers, a 50 MW cap for any single solar power plant's installed capacity, and large consumers not allowed to sign long-term power purchase agreements for new solar installations. Ember says there is technical potential for 120 GW of rooftop solar, almost 10 times 2023 capacity, which they say could generate 45% of the country’s 2022 demand.

Background

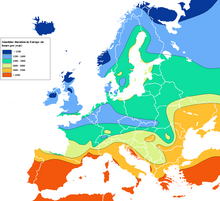

Turkey has a sunny climate, ideal for producing solar power. There are about 2600 hours of sunshine each year (about 7 hours a day), almost twice that of Germany, yet Germany has much more solar capacity. Turkey's average annual solar irradiance is over 1 million terrawatt-hours, that is about 1500 kW·h/(m·yr) or over 4 kW·h/(m·d). Covering less than 5% of the country's land area with solar panels would provide all the energy needed. Solar power may also be preferable to other renewable energy sources such as wind power and hydroelectricity because wind speed and rainfall can be low in summer, which is when demand peaks due to air conditioning.

Solar water heating has been commonplace in Turkey since the 1970s, but the first licences for solar electricity generation were not granted until 2014. Fatih Birol, executive director of the International Energy Agency (IEA), said that in 2021 less than 3% of solar potential was being used.

Policies and laws

The country plans to increase capacity to almost 53 GW by 2035. Systems producing over 5 megawatts (MW) of power must be licensed by the Energy Market Regulatory Authority if they feed into the grid.

Since 2021 feed-in tariffs for new installations have been in lira (but are maximum about US$0.05 per kWh) and set by the president, but the 10-year period has been criticised as too short. In 2022 there are many applications for hybrid solar and wind licences. As of 2022 there are 9 renewable energy cooperatives; it has been suggested that agricultural energy cooperatives would be profitable if farmers had more loans and technical help to establish them. Another state aid model in support of solar power is the so-called "YEKA" (abbreviation for "Yenilenebilir Enerji Kaynak Alanları", Renewable Energy Source Areas) model, prioritizing local content manufacturing or use. A successful application of the YEKA was the "Karapınar Solar Energy Plant" in Konya, with 1.000 MWe installed capacity.

According to think tank Ember, building new wind and solar power is cheaper than running existing coal plants which depend on imported coal. But they say that there are obstacles to building utility-scale solar, such as lack of new capacity allocated for solar power at transformers, a 50 MW cap for any single solar power plant's installed capacity, and large consumers being unable to sign long-term power purchase agreements for new unlicensed solar installations. Ember recommend that rooftop solar should be obligatory on new buildings in Turkey. Owners of these small unlicensed installations can sell to the grid at the same price as they buy.

Economics

As in many countries for many types of variable renewable energy, from time to time the government invites companies to tender sealed bids to construct a certain capacity of solar power to connect to certain electricity substations. By accepting the lowest bid the government commits to buy at that price per kWh for a fixed number of years, or up to a certain total amount of power. This provides certainty for investors against highly volatile wholesale electricity prices. However they may still risk exchange rate volatility if they borrowed in foreign currency. For example as Turkey does not have enough solar cell manufacturing capacity they would likely be bought from China and so would have to be paid for in foreign currency. In 22/23 a third of solar cell exports from China went to Turkey. However they are subject to tariffs.

In 2021 prices at these "solar auctions" were similar to or lower than average wholesale electricity prices, and large-scale solar for companies own use is also competitive; but macroeconomic challenges and exchange rate volatility are causing uncertainty. Installation costs are low and according to the Turkish Solar Energy Industry Association the industry provides jobs for 100,000 people. As part of the fourth round of solar auctions which are planned to total 1000 MW in lots of 50 MW and 100 MW, in April 2022 three lots of 100 MW were auctioned at prices around 400 lira per MWh, around 25 euros at the exchange rate at that time. The tender included a 60% foreign exchange weight clause, which partly protects against currency volatility, and selling on the open market is also allowed.

Modelling by Carbon Tracker indicates that new solar power will become cheaper than all existing coal plants by 2023. According to a May 2022 report from think tank Ember wind and solar saved 7 billion dollars on gas imports in the preceding 12 months. Every gigawatt of solar power installed would save over US$100 million on gas import costs. According to a 2022 study by Shura almost all coal power could be replaced by renewables (mainly solar) by 2030. Export of solar power could increase together eventually with hydrogen produced by clean electricity. Operation and maintenance costs of concentrated solar power is about 2 UScent/kWh. As well as reducing electricity prices, above a certain level increasing solar power tends to stabilize them.

In 2023 a standard module made in Turkey cost about 40 uscents compared to about 25 elsewhere.

Heating and hot water

Sales of vacuum tube hot water systems have exceeded flat-plate collectors since 2019. Vacuum tubes are more efficient for households than flat plate. Turkey is second in the world in solar water heating collector capacity after China, with about 26 million square metres generating 1.15 million tonnes of oil equivalent heat energy each year. About two-thirds is residential and a third industrial. Installed domestic hot water systems are typically convection without pumping, with 2 flat plate collectors, each nearly 2 m². Solar combi (space and water heating backed up by gas) is starting to be installed in villas and hotels.

The industry is well developed for hot water with high quality manufacturing and export capacity, but less so for space heating, and is hampered by subsidies for coal heating. A 2018 study found that solar water heating saved on average 13% energy and increased the value of properties.

In 2021 the IEA recommended that the Turkish government should support solar water heating because "technology and infrastructure quality needs to improve significantly to maximise its potential".

Solar heating is also used for agriculture in Turkey, for example drying produce with solar air heaters.

Photovoltaics

Photovoltaics (PV) growth was supported by the government during the 2010s. Monthly average efficiencies are from 12–17% depending on tilt and climate type; specific yield decreases with elevation. In 2020 solar cell manufacturing started in Turkey, and in 2022 Minister of Energy and Natural Resources Fatih Dönmez claimed that Turkey could assemble enough solar panels annually to produce 8 GW of power. Industry sometimes uses its own solar power for processes which need a lot of electricity, such as electrolysis. As of 2020, unlike in the EU, obsolete solar panels are not classified as electronic waste and recycling criteria are not defined. Solar PV has been suggested at public charging stations. Turkey's greenhouse gas emissions attributable to solar PV are estimated at around 30 g Co2eq/kWh for utility scale and 30–60 g for rooftop; emissions for coal and natural gas are over 1000 g and about 400 g respectively.

Solar farms

The largest solar farm is Karapınar, which started generation in 2020 and is planned to exceed 1 GW by the end of 2022. If a solar power plant is not cleaned for a year it can lose over 5% efficiency. Environmental groups say that half of opencast mines for brown coal (lignite) in Turkey could be converted to 13 GW of solar farms (some with battery storage) generating 19 TWh per year, as much of the electrical infrastructure is already in place for the 10 GW of the 22 adjacent lignite-fired power stations. Aluminium producers favour solar as they use a lot of electricity for electrolysis.

Rooftop

As of 2022 there is about 1 GW of rooftop solar, companies are installing a lot, and the government is aiming for 2–4 GW by the early 2030s. If total electricity generated by solar panels exceeds 50% of the capacity of the local distribution transformer no more will be approved in that area.

Residential

The limit for a household is 10 kW. The payback period is very long because electricity from the grid to householders is subsidised a lot. As of 2019, the payback period of rooftop solar with net metering for homeowners and businesses was estimated at 11 years; removal of VAT and the fixed government approval fee, and attaching borrowing for installation to the property's mortgage has been suggested to shorten this.

Non-residential

In general non-residential grid power is more expensive than residential, so the payback period is much shorter. From 2023 new buildings larger than 5,000 square meters will have to generate at least five per cent of their energy from renewables. A 2021 study in Ankara found far more rooftop potential for public and commercial buildings than residential. The study also suggested increasing technical potential by suitable roof design in new buildings. Solar PV used with heat pumps may be able to make buildings zero energy in the Mediterranean Region. Aluminium producer Tosyalı claimed in 2022 to be installing the world's largest rooftop solar power system on the roofs of its buildings.

Agriculture

Farmers are financially supported to install solar panels, for example to power irrigation pumps, and can sell some electricity. Agrivoltaics has been suggested as suitable for wheat, maize and some other shade-loving vegetables. Hybrid solar and biogas has been suggested, for example on dairy farms. Rainwater harvesting has been suggested.

Alternatives to photovoltaics

Mehmet Bulut of the Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources suggested in 2021 that concentrated solar power (CSP) could be co-located with photovoltaics in the south-east. CSP systems generate electricity by using lenses or mirrors to reflect the sun's rays onto a central receiver, which converts the light into heat, which in turn is converted to electricity. Turkey's first solar power tower, the Greenway CSP Mersin Solar Tower Plant in Mersin, was constructed in 2013 and has an installed power of 5 MW.

A solar updraft tower has been suggested for Antalya Province.

See also

- Renewable energy in Turkey

- Wind power in Turkey

- Geothermal power in Turkey

- Biofuel in Turkey

- Hydroelectricity in Turkey

Further reading

- "Turkey: Status of Solar Heating/Cooling and Solar Buildings – 2021". www.iea-shc.org. Retrieved 17 May 2022.

- Cagdas Artantas, Onur (2023) "Green Electricity Promotion in Turkey", Promotion of Green Electricity in Germany and Turkey: A Comparison with Reference to the WTO and EU Law, Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland, pp. 169–187, doi:10.1007/978-3-031-44760-0_7, ISBN 978-3-031-44760-0,

References

- ^ "Turkey Country Report". International Energy Agency Solar heating and cooling. 2021. Retrieved 17 May 2022.

- ^ Acaroğlu, Hakan; García Márquez, Fausto Pedro (8 May 2022). "A life-cycle cost analysis of High Voltage Direct Current utilization for solar energy systems: The case study in Turkey". Journal of Cleaner Production. 360: 132128. Bibcode:2022JCPro.36032128A. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.132128. ISSN 0959-6526.

- ^ Dawood, Kamran (2016). "Hybrid wind-solar reliable solution for Turkey to meet electric demand". Balkan Journal of Electrical and Computer Engineering. 4 (2): 62–66. doi:10.17694/bajece.06954 (inactive 1 November 2024).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ First Biennial Transparency Report of Türkiye (PDF) (Report). Ministry of Environment, Urbanisation and Climate Change. November 2024.

- ^ Türkiye Electricity Review 2024 (PDF) (Report). Ember.

- ^ "Renewables Global Status Report". REN21. Archived from the original on 24 May 2019. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ^ Overview of the Turkish Electricity Market (Report). PricewaterhouseCoopers. October 2021. Archived from the original on 28 November 2021. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- ^ "2022 energy outlook" (PDF). Industrial Development Bank of Turkey.

transferring money from solar, wind and hydroelectric power plants with low operating costs to power plants with high operating costs such as imported coal and natural gas

- ^ "Solar is key in reducing Turkish gas imports". Hürriyet Daily News. 19 February 2020. Archived from the original on 6 April 2020. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ^ Matalucci, Sergio (30 March 2022). "Turkey targets Balkans and EU renewables markets". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 19 May 2022.

- ^ Başgül, Erdem (16 May 2022). "Hot Topics In Turkish Renewable Energy Market". Mondaq. Retrieved 17 May 2022.

- ^ Todorović, Igor (8 March 2022). "Hybrid power plants dominate Turkey's new 2.8 GW grid capacity allocation". Balkan Green Energy News. Retrieved 7 July 2022.

- ^ "Turkey: New wind and solar power now cheaper than running existing coal plants relying on imports". Ember. 27 September 2021. Archived from the original on 29 September 2021. Retrieved 29 September 2021.

- ^ "Türkiye Electricity Review 2023". Ember. 13 March 2023. Retrieved 29 March 2023.

- ^ "Türkiye can expand solar by 120 GW through rooftops". Ember. 11 December 2023. Retrieved 28 December 2023.

- ^ "Solar". Republic of Turkey Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources. Archived from the original on 24 January 2021. Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- ^ Çeçen, Mehmet; Yavuz, Cenk; Tırmıkçı, Ceyda Aksoy; Sarıkaya, Sinan; Yanıkoğlu, Ertan (7 January 2022). "Analysis and evaluation of distributed photovoltaic generation in electrical energy production and related regulations of Turkey". Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy. 24 (5): 1321–1336. Bibcode:2022CTEP...24.1321C. doi:10.1007/s10098-021-02247-0. ISSN 1618-9558. PMC 8736286. PMID 35018170.

- ^ "Turkey take the winding road to solar success". Norton Rose Fulbright. February 2020. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

- ^ "The Sky's the Limit: Solar and wind energy potential". Carbon Tracker Initiative. Archived from the original on 30 April 2021. Retrieved 1 May 2021.

- ^ O'Byrne, David (9 August 2021). "Turkey faces double whammy as low hydro aligns with gas contract expiries". S & P Global. Archived from the original on 17 March 2022. Retrieved 17 March 2022.

- ^ "Non-hydro renewables overtake hydro for first time". Hürriyet Daily News. 22 January 2022.

- ^ "Türkiye to increase energy investments with zero emission target". Hürriyet Daily News. 21 January 2023. Retrieved 21 January 2023.

- ^ "Amendments In The Law On Utilization Of Renewable Energy Sources For The Purpose Of Generating Electrical Energy". Mondaq. Archived from the original on 19 February 2022. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ Kılıç, Uğur; Kekezoğlu, Bedri (1 September 2022). "A review of solar photovoltaic incentives and Policy: Selected countries and Turkey". Ain Shams Engineering Journal. 13 (5): 101669. doi:10.1016/j.asej.2021.101669. ISSN 2090-4479. S2CID 246212766.

- ^ "2021 was record year for annual wind installations in Turkey". Balkan Green Energy News. 6 January 2022. Archived from the original on 21 January 2022. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ^ "Türkiye'deki güneş enerjisi kooperatifleri, ithal enerji yüküne ne kadar çözüm olabilir?" [How much can solar energy cooperatives in Turkey relieve the imported energy burden?]. BBC News Türkçe (in Turkish). Retrieved 14 May 2022.

- ^ Everest, Bengü (15 March 2021). "Willingness of farmers to establish a renewable energy (solar and wind) cooperative in NW Turkey". Arabian Journal of Geosciences. 14 (6): 517. Bibcode:2021ArJG...14..517E. doi:10.1007/s12517-021-06931-9. ISSN 1866-7538. PMC 7956873.

- ^ Cagdas Artantas, Onur (2023), Cagdas Artantas, Onur (ed.), "Green Electricity Promotion in Turkey", Promotion of Green Electricity in Germany and Turkey: A Comparison with Reference to the WTO and EU Law, European Yearbook of International Economic Law, vol. 33, Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland, pp. 169–187, doi:10.1007/978-3-031-44760-0_7, ISBN 978-3-031-44760-0, retrieved 8 September 2024

- ^ "Karapınar Güneş Enerji Santrali". Enerji Atlası (in Turkish). Retrieved 8 September 2024.

- ^ "Turkey: Wind and solar saved $7 bn in 12 months". Ember. 24 May 2022. Retrieved 26 May 2022.

- ^ "Renewable Energy Auctions Toolkit | Energy | U.S. Agency for International Development". USAID. 28 July 2021. Retrieved 19 May 2022.

- ^ "Feed-In Tariffs vs Reverse Auctions: Setting the Right Subsidy Rates for Solar". Development Asia. 10 November 2021. Retrieved 19 May 2022.

- ^ "Government hits accelerator on low-cost renewable power". UK government. Retrieved 19 May 2022.

- ^ "Currency Risk Is the Hidden Solar Project Deal Breaker". greentechmedia.com. Retrieved 19 May 2022.

- ^ "Regional distribution of solar module production". Statista. Retrieved 19 May 2022.

- ^ "Solar exports from China increase by a third". 13 September 2023.

- ^ Abernethy, Brad (25 March 2024). "Turkey introduces duties on PV module imports from 5 countries". pv magazine International. Retrieved 13 July 2024.

- ^ "Renewables 2021 – Analysis". International Energy Agency. December 2021. Archived from the original on 3 December 2021. Retrieved 3 December 2021.

- ^ "Turkey". climateactiontracker.org. Retrieved 1 May 2022.

- ^ Sırt, Timur (18 March 2022). "Technology, retail giants embrace solar power". Daily Sabah. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

- ^ "Terms of Reference regarding the YEKA-GES-4 Auction are Changed". gonen.com.tr. Retrieved 17 April 2022.

- ^ "YEKA GES 4 Yarışma Sonuçları-8 Nisan 2022 – Güneş". Solarist – Güneş Enerjisi Portalı (in Turkish). 8 April 2022. Retrieved 17 April 2022.

- ^ "Turkey completes solar power auction for 300 MW". Balkan Green Energy News. 11 April 2022. Retrieved 17 April 2022.

- ^ "Global Coal Power Economics Model Methodology" (PDF). Carbon Tracker. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 March 2020. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ^ "Wind vs Coal power in Turkey/Solar PV vs Coal in Turkey" (PDF). Carbon Tracker. 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 March 2020. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ^ "Integration of Renewable Energy into the Turkish Electricity System". Shura. 28 April 2022. Retrieved 17 May 2022.

- ^ Chandak, Pooja (4 May 2022). "Turkey is Very Important for Energy Diversification plans of the European Union Says EU Minister". SolarQuarter. Retrieved 19 May 2022.

- ^ "Renewable Power Generation Costs in 2021". /publications/2022/Jul/Renewable-Power-Generation-Costs-in-2021. 13 July 2022. Archived from the original on 10 July 2024. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- ^ Peker, Mustafa Çağrı (19 September 2023). "Evolution of Electricity Markets from the Perspective of Production and Organized Markets".

- ^ "Weekend Read: A manufacturing bridge between Europe and Asia". 13 May 2023.

- ^ Siampour, Leila; Vahdatpour, Shoeleh; Jahangiri, Mehdi; Mostafaeipour, Ali; Goli, Alireza; Shamsabadi, Akbar Alidadi; Atabani, Abdulaziz (1 February 2021). "Techno-enviro assessment and ranking of Turkey for use of home-scale solar water heaters". Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments. 43. Elsevier: 100948. Bibcode:2021SETA...4300948S. doi:10.1016/j.seta.2020.100948. ISSN 2213-1388.

- ^ "Turkey 2019". Environmental Performance Reviews. OECD Environmental Performance Reviews. OECD. February 2019. doi:10.1787/9789264309753-en. ISBN 978-92-64-30974-6. S2CID 242969625.

- ^ Aydin, Erdal; Eichholtz, Piet; Yönder, Erkan (1 September 2018). "The economics of residential solar water heaters in emerging economies: The case of Turkey". Energy Economics. 75: 285–299. Bibcode:2018EneEc..75..285A. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2018.08.001. ISSN 0140-9883. S2CID 158839915. Archived from the original on 12 June 2020. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- ^ "Renewable Energy Engineering, Research and Applications Center". Karabük University. Retrieved 17 May 2022.

- ^ Ozden, Talat (14 January 2022). "A countrywide analysis of 27 solar power plants installed at different climates". Scientific Reports. 12 (1): 746. Bibcode:2022NatSR..12..746O. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-04551-7. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 8760320. PMID 35031638.

- ^ Bir, Burak; Aliyev, Jeyhun (5 July 2020). "Turkey to open 1st domestic solar panel factory in Aug". Anadolu Agency. Archived from the original on 7 July 2020. Retrieved 6 July 2020.

- ^ "Dönmez: Turkey is world's No. 4 solar panel producer". Balkan Green Energy News. 6 May 2022. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ^ "Turkish aluminum producer building solar power plants to reach net zero emissions". Balkan Green Energy News. 2 February 2022. Archived from the original on 8 March 2022. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- ^ Erat, Selma; Telli, Azime (2020). "Within the global circular economy: A special case of Turkey towards energy transition". MRS Energy & Sustainability. 7 (1): 24. doi:10.1557/mre.2020.26. ISSN 2329-2229. PMC 7849225. PMID 38624537.

- ^ Turan, Mehmet Tan; Gökalp, Erdin (1 March 2022). "Integration Analysis of Electric Vehicle Charging Station Equipped with Solar Power Plant to Distribution Network and Protection System Design". Journal of Electrical Engineering & Technology. 17 (2): 903–912. Bibcode:2022JEET...17..903T. doi:10.1007/s42835-021-00927-x. ISSN 2093-7423. S2CID 244615183.

- ^ Kursun, Berrin (9 April 2022). "Role of solar power in shifting the Turkish electricity sector towards sustainability". Clean Energy. 6 (2). Oxford University Press: 1078–1089. doi:10.1093/ce/zkac002.

- ^ "GE Renewable Energy and Kalyon to power Turkey with 1.3 GW solar projects". TR MONITOR. 23 September 2021. Archived from the original on 26 September 2021. Retrieved 26 September 2021.

- ^ "Category A project supported: Kaparinar Yeka (Kalyon) Solar Power Plant, Turkey". GOV.UK. Archived from the original on 7 March 2022. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- ^ Şevik, Seyfi; Aktaş, Ahmet (1 January 2022). "Performance enhancing and improvement studies in a 600kW solar photovoltaic power plant; manual and natural cleaning, rainwater harvesting and the snow load removal on the PV arrays". Renewable Energy. 181: 490–503. Bibcode:2022REne..181..490S. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2021.09.064. ISSN 0960-1481. S2CID 239336676.

- ^ "Turkey's open-cast coal mines can host enough solar to power almost seven million homes". Europe Beyond Coal. 23 March 2022. Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ^ Todorović, Igor (2 February 2022). "Turkish aluminum producer building solar power plants to reach net zero emissions". Balkan Green Energy News.

- ^ "GÜNDER Yönetim Kurulu Başkanı Kaleli: Çatı tipi güneş santrali pazarında başvuru sayısı 2 bini geçti" [Solar Association Chairman Kaleli: More than 2000 solar rooftop applications] (in Turkish). Anadolu Agency. Archived from the original on 7 March 2022. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- ^ "Turkish Companies Go Solar at Record Pace to Cut Energy Costs". Bloomberg.com. 1 December 2022. Retrieved 3 December 2022.

- ^ "Solar photovoltaics in CEE: Prospects for installation & utilization". cms.law. Archived from the original on 7 March 2022. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- ^ Flora, Arjun; Özenç, Bengisu; Wynn, Gerard (December 2019). "New Incentives Brighten Turkey's Rooftop Solar Sector" (PDF). Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 December 2019. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- ^ "Buildings to be required to use renewable energy". Hürriyet Daily News. 20 February 2022. Archived from the original on 7 March 2022. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- ^ Kutlu, Elif Ceren; Durusoy, Beyza; Ozden, Talat; Akinoglu, Bulent G. (1 February 2022). "Technical potential of rooftop solar photovoltaic for Ankara". Renewable Energy. 185: 779–789. Bibcode:2022REne..185..779K. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2021.12.079. ISSN 0960-1481. S2CID 245392035.

- ^ Zaferanchi, Mahdiyeh; Sozer, Hatice (1 January 2022). "Effectiveness of interventions to convert the energy consumption of an educational building to zero energy". International Journal of Building Pathology and Adaptation. 42 (4). Emerald Publishing Limited: 485–509. doi:10.1108/IJBPA-08-2021-0114. ISSN 2398-4708. S2CID 247355490.

- ^ "Turkish aluminum producer Tosyalı launches world's biggest rooftop solar project". Balkan Green Energy News. 23 March 2022. Retrieved 17 April 2022.

- ^ Todorović, Igor (18 March 2022). "Turkey to grant 40% to farmers for solar power systems – report". Balkan Green Energy News.

- ^ "Son dakika… Bakan Nebati: 15 yılda tamamlanacak projeleri 2 yılda bitireceğiz". Hürriyet (in Turkish). 21 March 2022. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ Parkinson, Simon; Hunt, Julian (14 July 2020). "Economic Potential for Rainfed Agrivoltaics in Groundwater-Stressed Regions". Environmental Science & Technology Letters. 7 (7): 525–531. Bibcode:2020EnSTL...7..525P. doi:10.1021/acs.estlett.0c00349. ISSN 2328-8930. S2CID 225824571.

- ^ Atıl Emre, Coşgun (16 June 2021). "The potential of Agrivoltaic systems in Turkey". Energy Reports. 7: 105–111. Bibcode:2021EnRep...7..105C. doi:10.1016/j.egyr.2021.06.017. ISSN 2352-4847.

- ^ Kirim, Yavuz; Sadikoglu, Hasan; Melikoglu, Mehmet (1 April 2022). "Technical and economic analysis of biogas and solar photovoltaic (PV) hybrid renewable energy system for dairy cattle barns". Renewable Energy. 188: 873–889. Bibcode:2022REne..188..873K. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2022.02.082. ISSN 0960-1481. S2CID 247114342.

- ^ Bulut, Mehmet (19 July 2021). "Integrated solar power project based on CSP and PV technologies for Southeast of Turkey". International Journal of Green Energy. 19 (6). Informa UK Limited: 603–613. doi:10.1080/15435075.2021.1954006. ISSN 1543-5075. S2CID 237718860. Archived from the original on 18 March 2022. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ^ Benmayor, Gila (23 April 2013). "Solar tower at Mersin". Hürriyet Daily News. Archived from the original on 20 February 2017. Retrieved 10 February 2014.

- ^ Ikhlef, Khaoula; Üçgül, İbrahim; Larbi, Salah; Ouchene, Samir (2022). "Performance estimation of a solar chimney power plant (SCPP) in several regions of Turkey". Journal of Thermal Engineering. 8 (2): 202. doi:10.18186/thermal.1078957 (inactive 1 November 2024).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link)