St Catherine's Monastery

The monastery was built by the orders of the Byzantine Emperor Justinian I, enclosing what is claimed to be the burning bush seen by Moses. Centuries later, the purported body of Saint Catherine of Alexandria, said to have been found in the area, was taken to the monastery; Saint Catherine's relics turned it into an important pilgrimage site, and the monastery was eventually renamed after the saint.

Controlled by the autonomous Church of Sinai, which is part of the wider Greek Orthodox Church, the monastery became a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2002 for its unique importance to the three major Abrahamic religions: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.

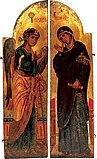

The monastery library holds unique and rare works, such as the Codex Sinaiticus and the Syriac Sinaiticus, as well as a collection of early Christian icons, including the earliest known depiction of Jesus as Christ Pantocrator.

Saint Catherine's has as its backdrop the three mountains it lies near: Ras Sufsafeh (possibly the Biblical Mount Horeb, peak c.1 km (0.62 mi) west); Jebel Arrenziyeb, peak c. 1km south; and Mount Sinai (locally, Jabal Musa, by tradition identified with the biblical Mount Sinai; peak c. 2 km (1.2 mi) south).

Christian traditions

The monastery was built around the location of what is traditionally considered to be the place of the burning bush seen by the Hebrew prophet Moses. Saint Catherine's monastery also encloses the "Well of Moses", where Moses is said to have met his future wife, Zipporah. The well is still today one of the monastery's main sources of water. The site is considered sacred by the three major Abrahamic religions: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.

Centuries after its foundation, the body of Saint Catherine of Alexandria was said to be found in a cave in the area. Catherine was a popular saint in Europe during the Middle Ages; her story says that, for defending Christianity, she was sentenced to death on a spiked breaking wheel, but, at her touch, the wheel shattered. It was then ordered that she be beheaded.

The relics of Saint Catherine, kept to this day inside the monastery, have made it a favourite site of pilgrimage. The patronal feast of the monastery is the Feast of the Transfiguration.

-

Saint Catherine's Monastery with Willow Peak (traditionally considered Mount Horeb) in the background

-

The monastery's centuries-old bramble is considered to be the biblical burning bush.

-

Skeleton of the monk Stephanos, in his robe, in front of the ossuary

History

The oldest record of monastic life at Mount Sinai comes from the travel journal written in Latin by a pilgrim woman named Egeria (Etheria; Saint Sylvia of Aquitaine) about 381/2–386.

The monastery was built by order of Emperor Justinian I (reigned 527–565), enclosing the Chapel of the Burning Bush (also known as "Saint Helen's Chapel") ordered to be built by Empress Consort Helena, mother of Constantine the Great, at the site where Moses is supposed to have seen the burning bush. The living bush on the grounds is purportedly the one seen by Moses. Structurally the monastery's king post truss is the oldest known surviving roof truss in the world.

From the time of the First Crusade, the presence of Crusaders in the Sinai until 1270 spurred the interest of European Christians and increased the number of intrepid pilgrims who visited the monastery. The monastery was supported by its dependencies in Egypt, Palestine, Syria, Crete, Cyprus and Constantinople. Throughout the Middle Ages, the monastery had a multiethnic profile, with monks of Arab, Greek, Syrian, Slavonic and Georgian origin. However, in the Ottoman period the monastic community became almost exclusively Greek, possibly due to the decline and depopulation of Transjordanian Christian towns. From the 1480s onwards, the Wallachian princes started sending out alms to the monastery.

A mosque was created by converting an existing chapel during the Fatimid Caliphate (909–1171), which was in regular use until the era of the Mamluk Sultanate in the 13th century and is still in use today on special occasions. During the Ottoman Empire, the mosque was in desolate condition; it was restored in the early 20th century.

During the seventh century, the isolated Christian anchorites of the Sinai were eliminated: only the fortified monastery remained. The monastery is surrounded by the massive fortifications that have preserved it. Until the twentieth century, access was through a door high in the outer walls.

The monastery, along with several dependencies in the area, constitute the entire Church of Sinai, which is headed by an archbishop, who is also the abbot of the monastery. The exact administrative status of the church within the Eastern Orthodox Church is ambiguous: by some, including the church itself, it is considered autocephalous, by others an autonomous church under the jurisdiction of the Greek Orthodox Church of Jerusalem. The archbishop is traditionally consecrated by the Greek Orthodox Patriarch of Jerusalem; in recent centuries he has usually resided in Cairo. During the period of the Crusades which was marked by bitterness between the Orthodox and Catholic churches, the monastery was patronized by both the Byzantine emperors and the rulers of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, and their respective courts.

Dominican theologian Felix Fabri visited the monastery in the 15th century and provided a detailed account of it. He also described the monastery's gardens, noting the presence of "tall fruit trees, salad herbs, grass, and grain," and mentioning "more than three thousand olive trees, many fig-trees and pomegranates, and a store of almonds and other fruits." The olives were used to produce oil for lighting lamps and as a relish in the kitchen.