Turf-Einar

He is portrayed as a successful warrior and has various characteristics in common with the Norse God Odin but his historicity is not in doubt. The reasons for his nickname of "Turf" are not certain.

Sources

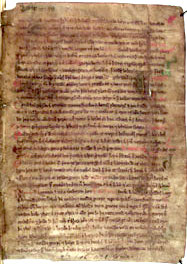

The sources for Einarr's life are exclusively the Norse sagas, none of which were written down during his lifetime. The Orkneyinga saga was first compiled in Iceland in the early 13th century and much of the information it contains is "hard to corroborate" according to scholars. Einarr is also referred to in the Heimskringla, which is of a similar vintage to the Orkneyinga saga. Torf-Einarr's Saga itself is now lost and a short passage is recorded in the Landnámabók. These verses, penned by Einarr himself about his feud with Hálfdan Long-Legs, were the source of most of the saga writer's information about him.

Family background

Einarr was the youngest son of Rognvald Eysteinsson, Jarl of Møre, by a concubine. According to the sagas and the Historia Norvegiae Rognvald's family conquered the Orkney and Shetland islands in the late ninth century. Rognvald's brother, Sigurd Eysteinsson, was made Jarl of Orkney and after his death on campaign he was succeeded by his son, Guthorm, who died shortly afterward. Rognvald then sent one of his own sons, Hallad, to govern the islands.

The Orkneyinga saga states that Einarr was one of six brothers, the others being: Hallad, Hrollaug, Ivar, Hrólfr, and Thorir the Silent. The three eldest, Hallad, Einarr and Hrollaug, were natural sons of Rognvald, and were "grown men when their brothers born in marriage were still children". Ivar was killed on an campaign with King Harald Finehair, which resulted in the Norðreyar being gifted to his family as compensation. Hrólfr "was so big that no horse could carry him", hence his byname of "Göngu-Hrólf" ("Hrólf the Walker"), and he is identified by the saga writers with Rollo, ancestor of the Dukes of Normandy. Thorir the Silent was Rognvald's third son by his marriage to Ragnhild.

Ari Þorgilsson quotes a short section from the lost Torf-Einarr’s Saga in the Landnámabók. It begins: "Earl Turf-Einarr (of Orkney) had a daughter in his youth, she was called Thordis. Earl Rognvald brought her up and gave her in marriage to Thorgeir Klaufi, their son was Einar, he went to Orkney to see his kinsmen; they would not own him for a kinsman; then Einar bought a ship in partnership with two brothers, Vestman and Vemund, and they went to Iceland." The Landnámabók goes on to make brief reference to Einar's travels there. It also lists his two sons, Eyjolf and Ljot, and some details about them and their descendants. The sagas describe Einarr as tall, ugly and blind in one eye, but sharp-sighted nonetheless.

Rise to power

Einarr's brother Hallad was unable to maintain control in Orkney due to the predations of Danish pirates. He resigned his earldom and returned to Norway as a common landholder, which "everyone thought was a huge joke." Hallad's failure led to Rognvald flying into a rage and summoning his sons Thorir and Hrolluag. He asked which of them wanted the islands but Thorir said the decision was up to the earl himself. Rognvald predicted that Thorir's path would keep him in Norway and that Hrolluag was destined seek his fortune in Iceland. Einarr, the youngest of the natural sons, then came forward and offered to go to the islands. Rognvald said: "Considering the kind of mother you have, slave-born on each side of her family, you are not likely to make much of a ruler. But I agree, the sooner you leave and the later you return the happier I'll be."

Rognvald agreed to provide Einarr with a ship and crew in the hope that he would sail away and never return. Despite his father's misgivings, on arrival in the Scottish islands, Einarr fought and defeated two Danish warlords, Þórir Tréskegg (Thorir Treebeard) and Kálf Skurfa (Kalf the Scurvy), who had taken residence there. Einarr then established himself as earl of a territory that comprised the two archipelagoes of Orkney and Shetland.

Relations with Norway

After Einarr had settled in Orkney two of Harald Finehair's unruly sons, Halvdan Hålegg (English: Hálfdan Longlegs) and Gudrød Ljome (English: Gudrod the Gleaming), killed Einarr's father Rognvald by trapping him in his house and setting it alight. Gudrød took possession of Rognvald's lands while Hálfdan sailed westwards to Orkney and then displaced Einarr. The sagas say that King Harald, apparently appalled by his sons' actions, overthrew Gudrød and restored Rognvald's lands to his son, Thorir. From a base in Caithness on the Scottish mainland Einarr resisted Hálfdan's occupation of the islands. After winning a battle at sea, and a ruthless campaign on land, Einarr spied Hálfdan hiding on North Ronaldsay. The sagas claim that Hálfdan was captured, and sacrificed to Odin as a blood eagle.

While the killing of Hálfdan by the Orkney islanders is recorded independently in the Historia Norvegiæ, the manner of his death is unspecified. The blood eagle sacrifice may be a misunderstanding or an invention of the sagawriters as it does not feature directly in the earlier skaldic verses, which instead indicate that Hálfdan was killed by a volley of spears. The verses do mention the eagle as a carrion bird, and this may have influenced the saga writers to introduce the blood eagle element. The sagas then relate that Harald sought vengeance for his son's ignoble death, and set out on campaign against Einarr, but was unable to dislodge him. Eventually, Harald agreed to end the fight in exchange for a fine of 60 gold marks levied on Einarr and the allodial owners of the islands. Einarr offered to pay the whole fine if the allodial landowners passed their lands to him, to which they agreed. Einarr's assumption of control over the islands appears well-attested and was considered by later commentators to be the moment at which the Earls of Orkney came to own the entire island group in fee to the King of Norway. Others have interpreted the payment of 60 gold marks as wergild or blood money.

The sagas incorrectly claim that the Earl of Orkney was called "Turf-Einarr" because he introduced the practice of burning turf or peat to the islands since wood was so scarce. This practice long pre-dates the Norse and the real reason for the nickname is unknown. The Orkneyinga saga has him organising peat cutting at Tarbat Ness far to the south of the Orkney heartland. While depletion of woodland could have caused a cultural shift from burning timber to peat, potentially the name arose because the sequestration of the common or allodial rights of the islanders by Einarr forced them away from coppicing towards cutting turves.

Legacy

The remainder of Einarr's long reign was apparently unchallenged, and he died in his bed of a sickness, leaving three sons, Arnkel, Erlend and Thorfinn who became jarls of Orkney after him. Despite his apparent physical shortcomings, as well as his low-born mother, Einarr established a dynasty which ruled the Orkney islands until 1470.

At this early period, many of the dates relating to the Orkney earldom are uncertain. Einarr's death is stated as being circa 910 in several sources. Crawford (2004) suggests he lived until the 930s and Ashley (1998) states that "allowing for the ages of his sons to succeed him he must have ruled to at least the year 920 or later."

There are five verses recorded in the Landnámabók attributed to Einarr that describe a feud between the families of Rognvald Eysteinsson and that of Harald Finehair. Apart from these verses, no other examples of Torf-Einarr's poetry are known to survive, though they appear to be part of a larger body of work. A couplet that commemorates Einarr's defeat of the two pirate Vikings, Thorir Treebeard and Kalf the Scurvy, has a matching metre and alliterative similarities to the attributed verses.

Hann gaf Tréskegg trollum, |

He gave Treebeard to the trolls, |

Einarr must have had some fame as a poet, as his name is used in the Háttatal, an examination of Old Norse poetry written in the thirteenth-century, to refer to a specific type of metre, Torf-Einarsháttr.

Interpretations

Much of Einarr's story in the sagas appears to be derived from the five skaldic verses attributed to Einarr himself and it is not certain that this account Einarr's conquest is historically accurate. Though the Historia Norvegiæ, written at the same time as the sagas but from a different source, confirms that Rognvald's family conquered the islands, it gives few details. The scene in the sagas where Einarr's father scorns him is a literary device which often figures in Old Norse literature. After Hallad's failure in Orkney the dialogue between the father and his sons has been interpreted as being about Rognvald's desire to cement his own position as Earl of Møre and an allusion to the early history of Iceland, where the sagas were written. Thorir is a compliant son who Rognvald is happy to keep at home. Hrolluag is portrayed as a man of peace who will go to Iceland. Einarr is aggressive and a threat to his father's position so can be spared for the dangers of Orkney. In the Landnámabók version the equally aggressive Hrolfr is also present, and his destiny is anticipated to be in conveniently far-away Normandy.

The writer of the Orkneyinga saga established Einarr's status in two contradictory ways. Although in the Historia Rognvald's family are described as "pirates" the saga provides them with a legally established earldom instated by the king. Einarr's success is however largely down to his own efforts and he negotiates with King Harald rather than offers blind obedience. The author is thus able to emphasise both the legitimacy and independence of his house.

Einarr is also provided with various characteristics associated with Odin. Both have but one eye and Halfdan's hideous death at Einarr's hands is offered to the god—an act that contains a hint of Odin's own sacrifice to himself in the Hávamál. Einarr is a man of action who is self-made, and he is a successful warrior who (unlike his brothers) avenges his father's death. He leads a dramatic and memorable life and emerges as "ancient, powerful and mysterious—but as a literary figure rather than a real person". He is also a heathen whose appearance at the commencement of the saga contrasts with the later martyrdom of his descendant St Magnus which marks a "moral high-point" of the story.

References

Notes

Footnotes

- ^ Smyth (1984) p. 153

- ^ Johnston, A.W. (July 1916) "Orkneyinga Saga". JSTOR/The Scottish Historical Review. Vol. 13, No. 52. p. 393. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- ^ Muir (2005) Preface: Genealogical table of the Earls of Orkney.

- ^ Crawford (1987) p. 54

- ^ Crawford (2004)

- ^ Woolf (2007) p. 242

- ^ Phelpstead (2001) p. 9

- ^ Thomson (2008) p. 30 quoting chapter 5 of the Orkneyinga saga.

- ^ Orkneyinga saga (1981) Chapter 4 - " To Shetland and Orkney" pp. 26–27

- ^ Saga of Harald Fairhair Chapter 24 - Rolf Ganger Driven Into Banishment.

- ^ “Landnámabók: Part 3” Archived 14 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Northvegr.org. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- ^ Heimskringla, Harald Harfager's saga, chapter 27; Orkneyinga saga, chapter 7

- ^ Orkneyinga saga (1981) Chapter 6 - "Forecasts" pp. 28–29.

- ^ Heimskringla, Harald Harfager's saga, chapter 27; Orkneyinga saga, chapters 6 and 7

- ^ Thomson (2008) p. 73

- ^ Heimskringla, Harald Harfager's saga, chapters 30 and 31; Orkneyinga saga, chapter 8

- ^ Poole (1991) p. 165

- ^ Frank, Roberta (April 1984) "Viking Atrocity and Skaldic Verse: The Rite of the Blood-Eagle". The English Historical Review 99 (391): 332–343 (Subscription required)

- ^ Heimskringla, Harald Harfager's saga, chapter 32; Orkneyinga saga, chapter 8

- ^ Woolf, p. 305

- ^ Smyth (1984) p. 154

- ^ Buckland, Paul (26 March 2002). "Review of The Christianization of Iceland, priests, power, and social change 1000–1300 by Orri Vésteinsson" Archived 2006-09-28 at the Wayback Machine. Institute for Historical Research, retrieved 25 August 2009.

- ^ Ashley (1998) p. 441

- ^ Poole (1991) pp. 169–170

- ^ Orkneyinga saga, chapter 7 "Vikings and Peat" p. 29

- ^ Pálsson and Edwards (1981) "Introduction" p. 13

- ^ Pálsson and Edwards (1981) "Introduction" p. 14

- ^ Thomson (2008) pp. 30–31

- ^ Thomson (2008) pp. 35–36

- ^ Thomson (2008) p. 38

General references

- Ashley, Michael (1998) The British Monarchs. Robinson Publishing. ISBN 1854875043

- Crawford, Barbara E. (1987) Scandinavian Scotland. Leicester University Press. ISBN 0718511972

- Crawford, Barbara E. (2004). "Einarr, earl of Orkney (fl. early 890s–930s)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, retrieved 20 July 2009 (Subscription required)

- Muir, Tom (2005) Orkney in the Sagas: The Story of the Earldom of Orkney as told in the Icelandic Sagas. The Orcadian. Kirkwall. ISBN 0954886232.

- Phelpstead, Karl (ed) (2001) A History of Norway and The Passion and Miracles of the Blessed Óláfr. (pdf) Translated by Devar Kunin. Viking Society for Northern Research Text Series. XIII. University of London.

- Poole, Russell Gilbert (1991). Viking Poems on War and Peace: A Study in Skaldic Narrative. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-6789-1

- Smyth, Alfred P. (1984) Warlords and Holy Men: Scotland AD 80–1000. Edinburgh University Press. Edinburgh. ISBN 0748601007

- Thomson, William P. L. (2008) The New History of Orkney. Edinburgh. Birlinn. ISBN 9781841586960

- Woolf, Alex (2007) From Pictland to Alba, 789–1070. Edinburgh. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 9780748612345

External links

- Torf-Einarr jarl Poetry attributed to Einarr (Old Norse)

- The Orkneyingers' Saga – 1894 translation by George Webbe Dasent