U.S. Dollars

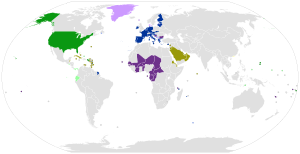

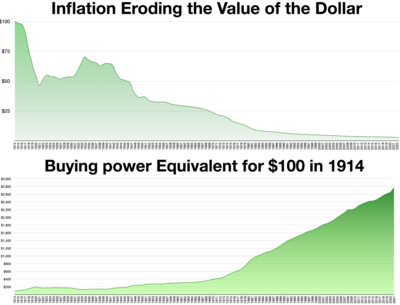

The U.S. dollar was originally defined under a bimetallic standard of 371.25 grains (24.057 g) (0.7734375 troy ounces) fine silver or, from 1834, 23.22 grains (1.505 g) fine gold, or $20.67 per troy ounce. The Gold Standard Act of 1900 linked the dollar solely to gold. From 1934, its equivalence to gold was revised to $35 per troy ounce. In 1971 all links to gold were repealed. The U.S. dollar became an important international reserve currency after the First World War, and displaced the pound sterling as the world's primary reserve currency by the Bretton Woods Agreement towards the end of the Second World War. The dollar is the most widely used currency in international transactions, and a free-floating currency. It is also the official currency in several countries and the de facto currency in many others, with Federal Reserve Notes (and, in a few cases, U.S. coins) used in circulation.

The monetary policy of the United States is conducted by the Federal Reserve System, which acts as the nation's central bank. As of February 10, 2021, currency in circulation amounted to US$2.10 trillion, $2.05 trillion of which is in Federal Reserve Notes (the remaining $50 billion is in the form of coins and older-style United States Notes). As of January 1, 2025, the Federal Reserve estimated that the total amount of currency in circulation was approximately US$2.37 trillion.

Overview

In the Constitution

Article I, Section 8 of the U.S. Constitution provides that Congress has the power "to coin money". Laws implementing this power are currently codified in Title 31 of the U.S. Code, under Section 5112, which prescribes the forms in which the United States dollars should be issued. These coins are both designated in the section as legal tender in payment of debts. The Sacagawea dollar is one example of the copper alloy dollar, in contrast to the American Silver Eagle which is pure silver. Section 5112 also provides for the minting and issuance of other coins, which have values ranging from one cent (U.S. Penny) to 100 dollars. These other coins are more fully described in Coins of the United States dollar.

Article I, Section 9 of the Constitution provides that "a regular Statement and Account of the Receipts and Expenditures of all public Money shall be published from time to time", which is further specified by Section 331 of Title 31 of the U.S. Code. The sums of money reported in the "Statements" are currently expressed in U.S. dollars, thus the U.S. dollar may be described as the unit of account of the United States. "Dollar" is one of the first words of Section 9, in which the term refers to the Spanish milled dollar, or the coin worth eight Spanish reales.

Coinage Act

In 1792, the U.S. Congress passed the Coinage Act, of which Section 9 authorized the production of various coins, including:

Dollars or Units—each to be of the value of a Spanish milled dollar as the same is now current, and to contain three hundred and seventy-one grains and four sixteenth parts of a grain of pure, or four hundred and sixteen grains of standard silver.

Section 20 of the Act designates the United States dollar as the unit of currency of the United States:

[T]he money of account of the United States shall be expressed in dollars, or units...and that all accounts in the public offices and all proceedings in the courts of the United States shall be kept and had in conformity to this regulation.

Decimal units

Unlike the Spanish milled dollar, the Continental Congress and the Coinage Act prescribed a decimal system of units to go with the unit dollar, as follows: the mill, or one-thousandth of a dollar; the cent, or one-hundredth of a dollar; the dime, or one-tenth of a dollar; and the eagle, or ten dollars. The current relevance of these units:

- Only the cent (¢) is used as everyday division of the dollar.

- The dime is used solely as the name of the coin with the value of 10 cents.

- The mill (₥) is relatively unknown, but before the mid-20th century was familiarly used in matters of sales taxes, as well as gasoline prices, which are usually in the form of $ΧΧ.ΧΧ9 per gallon (e.g., $3.599, commonly written as $3.59+9⁄10).

- The eagle is also largely unknown to the general public. This term was used in the Coinage Act of 1792 for the denomination of ten dollars, and subsequently was used in naming gold coins.

The Spanish peso or dollar was historically divided into eight reales (colloquially, bits) – hence pieces of eight. Americans also learned counting in non-decimal bits of 12+1⁄2 cents before 1857 when Mexican bits were more frequently encountered than American cents; in fact this practice survived in New York Stock Exchange quotations until 2001.

In 1854, Secretary of the Treasury James Guthrie proposed creating $100, $50, and $25 gold coins, to be referred to as a union, half union, and quarter union, respectively, thus implying a denomination of 1 Union = $100. However, no such coins were ever struck, and only patterns for the $50 half union exist.

When currently issued in circulating form, denominations less than or equal to a dollar are emitted as U.S. coins, while denominations greater than or equal to a dollar are emitted as Federal Reserve Notes, disregarding these special cases:

- Gold coins issued for circulation until the 1930s, up to the value of $20 (known as the double eagle)

- Bullion or commemorative gold, silver, platinum, and palladium coins valued up to $100 as legal tender (though worth far more as bullion).

- Civil War paper currency issue in denominations below $1, i.e. fractional currency, sometimes pejoratively referred to as shinplasters.

Etymology

In the 16th century, Count Hieronymus Schlick of Bohemia began minting coins known as joachimstalers, named for Joachimstal, the valley in which the silver was mined. In turn, the valley's name is titled after Saint Joachim, whereby thal or tal, a cognate of the English word dale, is German for 'valley.' The joachimstaler was later shortened to the German taler, a word that eventually found its way into many languages, including: tolar (Czech, Slovak and Slovenian); daler (Danish and Swedish); talar (Polish); dalar and daler (Norwegian); daler or daalder (Dutch); talari (Ethiopian); tallér (Hungarian); tallero (Italian); دولار (Arabic); and dollar (English).

Though the Dutch pioneered in modern-day New York in the 17th century the use and the counting of money in silver dollars in the form of German-Dutch reichsthalers and native Dutch leeuwendaalders ('lion dollars'), it was the ubiquitous Spanish American eight-real coin which became exclusively known as the dollar since the 18th century.

Nicknames

The colloquialism buck(s) (much like the British quid for the pound sterling) is often used to refer to dollars of various nations, including the U.S. dollar. This term, dating to the 18th century, may have originated with the colonial leather trade, or it may also have originated from a poker term.

Greenback is another nickname, originally applied specifically to the 19th-century Demand Note dollars, which were printed black and green on the backside, created by Abraham Lincoln to finance the North for the Civil War. It is still used to refer to the U.S. dollar (but not to the dollars of other countries). The term greenback is also used by the financial press in other countries, such as Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, and India.

Other well-known names of the dollar as a whole in denominations include greenmail, green, and dead presidents, the latter of which referring to the deceased presidents pictured on most bills. Dollars in general have also been known as bones (e.g. "twenty bones" = $20). The newer designs, with portraits displayed in the main body of the obverse (rather than in cameo insets), upon paper color-coded by denomination, are sometimes referred to as bigface notes or Monopoly money.

Piastre was the original French word for the U.S. dollar, used for example in the French text of the Louisiana Purchase. Though the U.S. dollar is called dollar in Modern French, the term piastre is still used among the speakers of Cajun French and New England French, as well as speakers in Haiti and other French Caribbean islands.

Nicknames specific to denomination:

- The quarter dollar coin is known as two bits, alluding the dollar's origins as the "piece of eight" (bits or reales).

- The $1 bill is nicknamed buck or single.

- The infrequently-used $2 bill is sometimes called deuce, Tom, or Jefferson (after Thomas Jefferson).

- The $5 bill is sometimes called Lincoln (after Abraham Lincoln), fin, fiver, or five-spot.

- The $10 bill is sometimes called sawbuck, ten-spot, or Hamilton (after Alexander Hamilton).

- The $20 bill is sometimes called double sawbuck, Jackson (after Andrew Jackson), or double eagle.

- The $50 bill is sometimes called a yardstick, or a grant, after President Ulysses S. Grant.

- The $100 bill is called Benjamin, Benji, Ben, or Franklin, referring to its portrait of Benjamin Franklin. Other nicknames include C-note (C being the Roman numeral for 100), century note, or bill (e.g. two bills = $200).

- Amounts or multiples of $1,000 are sometimes called grand in colloquial speech, abbreviated in written form to G, K, or k (from kilo; e.g. $10k = $10,000). Likewise, a large or stack can also refer to a multiple of $1,000 (e.g. "fifty large" = $50,000).

Dollar sign

The symbol $, usually written before the numerical amount, is used for the U.S. dollar (as well as for many other currencies). The sign was perhaps the result of a late 18th-century evolution of the scribal abbreviation p for the peso, the common name for the Spanish dollars that were in wide circulation in the New World from the 16th to the 19th centuries. The p and the s eventually came to be written over each other giving rise to $.

Another popular explanation is that it is derived from the Pillars of Hercules on the Spanish coat of arms of the Spanish dollar. These Pillars of Hercules on the silver Spanish dollar coins take the form of two vertical bars (||) and a swinging cloth band in the shape of an S.

Yet another explanation suggests that the dollar sign was formed from the capital letters U and S written or printed one on top of the other. This theory, popularized by novelist Ayn Rand in Atlas Shrugged, does not consider the fact that the symbol was already in use before the formation of the United States.

History

Origins: the Spanish dollar

The U.S. dollar was introduced at par with the Spanish-American silver dollar (or Spanish peso, Spanish milled dollar, eight-real coin, piece-of-eight). The latter was produced from the rich silver mine output of Spanish America, was minted in Mexico City, Potosí (Bolivia), Lima (Peru), and elsewhere, and was in wide circulation throughout the Americas, Asia, and Europe from the 16th to the 19th centuries. The minting of machine-milled Spanish dollars since 1732 boosted its worldwide reputation as a trade coin and positioned it to be the model for the new currency of the United States.

Even after the United States Mint commenced issuing coins in 1792, locally minted dollars and cents were less abundant in circulation than Spanish American pesos and reales; hence Spanish, Mexican, and American dollars all remained legal tender in the United States until the Coinage Act of 1857. In particular, colonists' familiarity with the Spanish two-real quarter peso was the reason for issuing a quasi-decimal 25-cent quarter dollar coin rather than a 20-cent coin.

For the relationship between the Spanish dollar and the individual state colonial currencies, see Connecticut pound, Delaware pound, Georgia pound, Maryland pound, Massachusetts pound, New Hampshire pound, New Jersey pound, New York pound, North Carolina pound, Pennsylvania pound, Rhode Island pound, South Carolina pound, and Virginia pound.

Coinage Act of 1792

On July 6, 1785, the Continental Congress resolved that the money unit of the United States, the dollar, would contain 375.64 grains of fine silver; on August 8, 1786, the Continental Congress continued that definition and further resolved that the money of account, corresponding with the division of coins, would proceed in a decimal ratio, with the sub-units being mills at 0.001 of a dollar, cents at 0.010 of a dollar, and dimes at 0.100 of a dollar.

After the adoption of the United States Constitution, the U.S. dollar was defined by the Coinage Act of 1792. It specified a "dollar" based on the Spanish milled dollar to contain 371+4⁄16 grains of fine silver, or 416.0 grains (26.96 g) of "standard silver" of fineness 371.25/416 = 89.24%; as well as an "eagle" to contain 247+4⁄8 grains of fine gold, or 270.0 grains (17.50 g) of 22 karat or 91.67% fine gold. Alexander Hamilton arrived at these numbers based on a treasury assay of the average fine silver content of a selection of worn Spanish dollars, which came out to be 371 grains. Combined with the prevailing gold-silver ratio of 15, the standard for gold was calculated at 371/15 = 24.73 grains fine gold or 26.98 grains 22K gold. Rounding the latter to 27.0 grains finalized the dollar's standard to 24.75 grains of fine gold or 24.75 × 15 = 371.25 grains = 24.0566 grams = 0.7735 troy ounces of fine silver.

The same coinage act also set the value of an eagle at 10 dollars, and the dollar at 1⁄10 eagle. It called for silver coins in denominations of 1, 1⁄2, 1⁄4, 1⁄10, and 1⁄20 dollar, as well as gold coins in denominations of 1, 1⁄2 and 1⁄4 eagle. The value of gold or silver contained in the dollar was then converted into relative value in the economy for the buying and selling of goods. This allowed the value of things to remain fairly constant over time, except for the influx and outflux of gold and silver in the nation's economy.

Though a Spanish dollar freshly minted after 1772 theoretically contained 417.7 grains of silver of fineness 130/144 (or 377.1 grains fine silver), reliable assays of the period in fact confirmed a fine silver content of 370.95 grains (24.037 g) for the average Spanish dollar in circulation. The new U.S. silver dollar of 371.25 grains (24.057 g) therefore compared favorably and was received at par with the Spanish dollar for foreign payments, and after 1803 the United States Mint had to suspend making this coin out of its limited resources since it failed to stay in domestic circulation. It was only after Mexican independence in 1821 when their peso's fine silver content of 377.1 grains was firmly upheld, which the U.S. later had to compete with using a heavier 378.0 grains (24.49 g) Trade dollar coin.

Design

The early currency of the United States did not exhibit faces of presidents, as is the custom now; although today, by law, only the portrait of a deceased individual may appear on United States currency. In fact, the newly formed government was against having portraits of leaders on the currency, a practice compared to the policies of European monarchs. The currency as we know it today did not get the faces they currently have until after the early 20th century; before that "heads" side of coinage used profile faces and striding, seated, and standing figures from Greek and Roman mythology and composite Native Americans. The last coins to be converted to profiles of historic Americans were the dime (1946), the half Dollar (1948), and the Dollar (1971).

Continental currency

After the American Revolution, the Thirteen Colonies became independent. Freed from British monetary regulations, they each issued £sd paper money to pay for military expenses. The Continental Congress also began issuing "Continental Currency" denominated in Spanish dollars. For its value relative to states' currencies, see Early American currency.

Continental currency depreciated badly during the war, giving rise to the famous phrase "not worth a continental". A primary problem was that monetary policy was not coordinated between Congress and the states, which continued to issue bills of credit. Additionally, neither Congress nor the governments of the several states had the will or the means to retire the bills from circulation through taxation or the sale of bonds. The currency was ultimately replaced by the silver dollar at the rate of 1 silver dollar to 1000 continental dollars. This resulted in the clause "No state shall... make anything but gold and silver coin a tender in payment of debts" being written into the United States Constitution article 1, section 10.

Silver and gold standards, 19th century

From implementation of the 1792 Mint Act to the 1900 implementation of the gold standard, the dollar was on a bimetallic silver-and-gold standard, defined as either 371.25 grains (24.056 g) of fine silver or 24.75 grains of fine gold (gold-silver ratio 15).

Subsequent to the Coinage Act of 1834 the dollar's fine gold equivalent was revised to 23.2 grains; it was slightly adjusted to 23.22 grains (1.505 g) in 1837 (gold-silver ratio ≈16). The same act also resolved the difficulty in minting the "standard silver" of 89.24% fineness by revising the dollar's alloy to 412.5 grains, 90% silver, still containing 371.25 grains fine silver. Gold was also revised to 90% fineness: 25.8 grains gross, 23.22 grains fine gold.

Following the rise in the price of silver during the California Gold Rush and the disappearance of circulating silver coins, the Coinage Act of 1853 reduced the standard for silver coins less than $1 from 412.5 grains to 384 grains (24.9 g), 90% silver per 100 cents (slightly revised to 25.0 g, 90% silver in 1873). The Act also limited the free silver right of individuals to convert bullion into only one coin, the silver dollar of 412.5 grains; smaller coins of lower standard can only be produced by the United States Mint using its own bullion.

Summary and links to coins issued in the 19th century:

- In base metal: 1/2 cent, 1 cent, 5 cents.

- In silver: half dime, dime, quarter dollar, half dollar, silver dollar.

- In gold: gold $1, $2.50 quarter eagle, $5 half eagle, $10 eagle, $20 double eagle.

- Less common denominations: bronze 2 cents, nickel 3 cents, silver 3 cents, silver 20 cents, gold $3.

Note issues, 19th century

In order to finance the War of 1812, Congress authorized the issuance of Treasury Notes, interest-bearing short-term debt that could be used to pay public dues. While they were intended to serve as debt, they did function "to a limited extent" as money. Treasury Notes were again printed to help resolve the reduction in public revenues resulting from the Panic of 1837 and the Panic of 1857, as well as to help finance the Mexican–American War and the Civil War.

Paper money was issued again in 1862 without the backing of precious metals due to the Civil War. In addition to Treasury Notes, Congress in 1861 authorized the Treasury to borrow $50 million in the form of Demand Notes, which did not bear interest but could be redeemed on demand for precious metals. However, by December 1861, the Union government's supply of specie was outstripped by demand for redemption and they were forced to suspend redemption temporarily. In February 1862 Congress passed the Legal Tender Act of 1862, issuing United States Notes, which were not redeemable on demand and bore no interest, but were legal tender, meaning that creditors had to accept them at face value for any payment except for import tariffs and interest on public debts. However, silver and gold coins continued to be issued, resulting in the depreciation of the newly printed notes through Gresham's law. In 1869, Supreme Court ruled in Hepburn v. Griswold that Congress could not require creditors to accept United States Notes, but overturned that ruling the next year in the Legal Tender Cases. In 1875, Congress passed the Specie Payment Resumption Act, requiring the Treasury to allow U.S. Notes to be redeemed for gold after January 1, 1879.

Gold standard, 20th century

Though the dollar came under the gold standard de jure only after 1900, the bimetallic era was ended de facto when the Coinage Act of 1873 suspended the minting of the standard silver dollar of 412.5 Troy grains = 26.73 g; 0.859 ozt, the only fully legal tender coin that individuals could convert bullion into in unlimited (or Free silver) quantities, and right at the onset of the silver rush from the Comstock Lode in the 1870s. This was the so-called "Crime of '73".

The Gold Standard Act of 1900 repealed the U.S. dollar's historic link to silver and defined it solely as 23.22 grains (1.505 g) of fine gold (or $20.67 per troy ounce of 480 grains). In 1933, gold coins were confiscated by Executive Order 6102 under Franklin D. Roosevelt, and in 1934 the standard was changed to $35 per troy ounce fine gold, or 13.71 grains (0.888 g) per dollar.

After 1968 a series of revisions to the gold peg was implemented, culminating in the Nixon Shock of August 15, 1971, which suddenly ended the convertibility of dollars to gold. The U.S. dollar has since floated freely on the foreign exchange markets.