Vice President Of The United States

The modern vice presidency is a position of significant power and is widely seen as an integral part of a president's administration. The presidential candidate selects the candidate for the vice presidency, as their running mate in the lead-up to the presidential election. While the exact nature of the role varies in each administration, since the vice president's service in office is by election, the president cannot dismiss the vice president, and the personal working-relationship with the president varies, most modern vice presidents serve as a key presidential advisor, governing partner, and representative of the president. The vice president is also a statutory member of the United States Cabinet and United States National Security Council and thus plays a significant role in executive government and national security matters. As the vice president's role within the executive branch has expanded, the legislative branch role has contracted; for example, vice presidents now preside over the Senate only infrequently.

The role of the vice presidency has changed dramatically since the office was created during the 1787 Constitutional Convention. Originally something of an afterthought, the vice presidency was considered an insignificant office for much of the nation's history, especially after the Twelfth Amendment meant that vice presidents were no longer the runners-up in the presidential election. The vice president's role began steadily growing in importance during the 1930s, with the Office of the Vice President being created in the executive branch in 1939, and has since grown much further. Due to its increase in power and prestige, the vice presidency is now often considered to be a stepping stone to the presidency. Since the 1970s, the vice president has been afforded an official residence at Number One Observatory Circle.

The Constitution does not expressly assign the vice presidency to a branch of the government, causing a dispute among scholars about which branch the office belongs to (the executive, the legislative, both, or neither). The modern view of the vice president as an officer of the executive branch—one isolated almost entirely from the legislative branch—is due in large part to the assignment of executive authority to the vice president by either the president or Congress. Nevertheless, many vice presidents have previously served in Congress, and are often tasked with helping to advance an administration's legislative priorities. JD Vance is the 50th and current vice president since January 20, 2025.

History and development

Constitutional Convention

No mention of an office of vice president was made at the 1787 Constitutional Convention until near the end, when an eleven-member committee on "Leftover Business" proposed a method of electing the chief executive (president). Delegates had previously considered the selection of the Senate's presiding officer, deciding that "the Senate shall choose its own President", and had agreed that this official would be designated the executive's immediate successor. They had also considered the mode of election of the executive but had not reached consensus. This all changed on September 4, when the committee recommended that the nation's chief executive be elected by an Electoral College, with each state having a number of presidential electors equal to the sum of that state's allocation of representatives and senators.

Recognizing that loyalty to one's individual state outweighed loyalty to the new federation, the Constitution's framers assumed individual electors would be inclined to choose a candidate from their own state (a so-called "favorite son" candidate) over one from another state. So they created the office of vice president and required the electors to vote for two candidates, at least one of whom must be from outside the elector's state, believing that the second vote would be cast for a candidate of national character. Additionally, to guard against the possibility that electors might strategically waste their second votes, it was specified that the first runner-up would become vice president.

The resultant method of electing the president and vice president, spelled out in Article II, Section 1, Clause 3, allocated to each state a number of electors equal to the combined total of its Senate and House of Representatives membership. Each elector was allowed to vote for two people for president (rather than for both president and vice president), but could not differentiate between their first and second choice for the presidency. The person receiving the greatest number of votes (provided it was an absolute majority of the whole number of electors) would be president, while the individual who received the next largest number of votes became vice president. If there were a tie for first or for second place, or if no one won a majority of votes, the president and vice president would be selected by means of contingent elections protocols stated in the clause.

Early vice presidents and Twelfth Amendment

The first two vice presidents, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, both of whom gained the office by virtue of being runners-up in presidential contests, presided regularly over Senate proceedings and did much to shape the role of Senate president. Several 19th-century vice presidents—such as George Dallas, Levi Morton, and Garret Hobart—followed their example and led effectively, while others were rarely present.

The emergence of political parties and nationally coordinated election campaigns during the 1790s (which the Constitution's framers had not contemplated) quickly frustrated the election plan in the original Constitution. In the election of 1796, Federalist candidate John Adams won the presidency, but his bitter rival, Democratic-Republican candidate Thomas Jefferson, came second and thus won the vice presidency. As a result, the president and vice president were from opposing parties; and Jefferson used the vice presidency to frustrate the president's policies. Then, four years later, in the election of 1800, Jefferson and fellow Democratic-Republican Aaron Burr each received 73 electoral votes. In the contingent election that followed, Jefferson finally won the presidency on the 36th ballot, leaving Burr the vice presidency. Afterward, the system was overhauled through the Twelfth Amendment in time to be used in the 1804 election.

19th and early 20th centuries

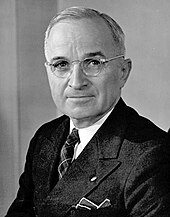

For much of its existence, the office of vice president was seen as little more than a minor position. John Adams, the first vice president, was the first of many frustrated by the "complete insignificance" of the office. To his wife Abigail Adams he wrote, "My country has in its wisdom contrived for me the most insignificant office that ever the invention of man ... or his imagination contrived or his imagination conceived; and as I can do neither good nor evil, I must be borne away by others and met the common fate." Thomas R. Marshall, who served as vice president from 1913 to 1921 under President Woodrow Wilson, lamented: "Once there were two brothers. One ran away to sea; the other was elected Vice President of the United States. And nothing was heard of either of them again." His successor, Calvin Coolidge, was so obscure that Major League Baseball sent him free passes that misspelled his name, and a fire marshal failed to recognize him when Coolidge's Washington residence was evacuated. John Nance Garner, who served as vice president from 1933 to 1941 under President Franklin D. Roosevelt, claimed that the vice presidency "isn't worth a pitcher of warm piss". Harry Truman, who also served as vice president under Franklin Roosevelt, said the office was as "useful as a cow's fifth teat". Walter Bagehot remarked in The English Constitution that "[t]he framers of the Constitution expected that the vice-president would be elected by the Electoral College as the second wisest man in the country. The vice-presidentship being a sinecure, a second-rate man agreeable to the wire-pullers is always smuggled in. The chance of succession to the presidentship is too distant to be thought of."

When the Whig Party asked Daniel Webster to run for the vice presidency on Zachary Taylor's ticket, he replied "I do not propose to be buried until I am really dead and in my coffin." This was the second time Webster declined the office, which William Henry Harrison had first offered to him. Ironically, both the presidents making the offer to Webster died in office, meaning the three-time candidate would have become president had he accepted either. Since presidents rarely die in office, however, the better preparation for the presidency was considered to be the office of Secretary of State, in which Webster served under Harrison, Tyler, and later, Taylor's successor, Fillmore.

In the first hundred years of the United States' existence no fewer than seven proposals to abolish the office of vice president were advanced. The first such constitutional amendment was presented by Samuel W. Dana in 1800; it was defeated by a vote of 27 to 85 in the United States House of Representatives. The second, introduced by United States Senator James Hillhouse in 1808, was also defeated. During the late 1860s and 1870s, five additional amendments were proposed. One advocate, James Mitchell Ashley, opined that the office of vice president was "superfluous" and dangerous.

Garret Hobart, the first vice president under William McKinley, was one of the very few vice presidents at this time who played an important role in the administration. A close confidant and adviser of the president, Hobart was called "Assistant President". However, until 1919, vice presidents were not included in meetings of the President's Cabinet. This precedent was broken by Woodrow Wilson when he asked Thomas R. Marshall to preside over Cabinet meetings while Wilson was in France negotiating the Treaty of Versailles. President Warren G. Harding also invited Calvin Coolidge, to meetings. The next vice president, Charles G. Dawes, did not seek to attend Cabinet meetings under President Coolidge, declaring that "the precedent might prove injurious to the country." Vice President Charles Curtis regularly attended Cabinet meetings on the invitation of President Herbert Hoover.

Emergence of the modern vice presidency

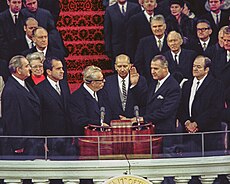

In 1933, Franklin D. Roosevelt raised the stature of the office by renewing the practice of inviting the vice president to cabinet meetings, which every president since has maintained. Roosevelt's first vice president, John Nance Garner, broke with him over the "court-packing" issue early in his second term, and became Roosevelt's leading critic. At the start of that term, on January 20, 1937, Garner had been the first vice president to be sworn into office on the Capitol steps in the same ceremony with the president, a tradition that continues. Prior to that time, vice presidents were traditionally inaugurated at a separate ceremony in the Senate chamber. Gerald Ford and Nelson Rockefeller, who were each appointed to the office under the terms of the 25th Amendment, were inaugurated in the House and Senate chambers respectively.

At the 1940 Democratic National Convention, Roosevelt selected his own running mate, Henry Wallace, instead of leaving the nomination to the convention, when he wanted Garner replaced. He then gave Wallace major responsibilities during World War II. However, after numerous policy disputes between Wallace and other Roosevelt Administration and Democratic Party officials, he was denied re-nomination at the 1944 Democratic National Convention. Harry Truman was selected instead. During his 82-day vice presidency, Truman was never informed about any war or post-war plans, including the Manhattan Project. Truman had no visible role in the Roosevelt administration outside of his congressional responsibilities and met with the president only a few times during his tenure as vice president. Roosevelt died on April 12, 1945, and Truman succeeded to the presidency (the state of Roosevelt's health had also been kept from Truman). At the time he said, "I felt like the moon, the stars and all the planets fell on me." Determined that no future vice president should be so uninformed upon unexpectedly becoming president, Truman made the vice president a member of the National Security Council, a participant in Cabinet meetings and a recipient of regular security briefings in 1949.

The stature of the vice presidency grew again while Richard Nixon was in office (1953–1961). He attracted the attention of the media and the Republican Party, when Dwight Eisenhower authorized him to preside at Cabinet meetings in his absence and to assume temporary control of the executive branch, which he did after Eisenhower suffered a heart attack on September 24, 1955, ileitis in June 1956, and a stroke in November 1957. Nixon was also visible on the world stage during his time in office.

Until 1961, vice presidents had their offices on Capitol Hill, a formal office in the Capitol itself and a working office in the Russell Senate Office Building. Lyndon B. Johnson was the first vice president to also be given an office in the White House complex, in the Old Executive Office Building. The former Navy Secretary's office in the OEOB has since been designated the "Ceremonial Office of the Vice President" and is today used for formal events and press interviews. President Jimmy Carter was the first president to give his vice president, Walter Mondale, an office in the West Wing of the White House, which all vice presidents have since retained. Because of their function as president of the Senate, vice presidents still maintain offices and staff members on Capitol Hill. This change came about because Carter held the view that the office of the vice presidency had historically been a wasted asset and wished to have his vice president involved in the decision-making process. Carter pointedly considered, according to Joel Goldstein, the way Roosevelt treated Truman as "immoral".

Another factor behind the rise in prestige of the vice presidency was the expanded use of presidential preference primaries for choosing party nominees during the 20th century. By adopting primary voting, the field of candidates for vice president was expanded by both the increased quantity and quality of presidential candidates successful in some primaries, yet who ultimately failed to capture the presidential nomination at the convention.

At the start of the 21st century, Dick Cheney (2001–2009) held much power within the administration, and frequently made policy decisions on his own, without the knowledge of the president. This rapid growth led to Matthew Yglesias and Bruce Ackerman calling for the abolition of the vice presidency while 2008's both vice presidential candidates, Sarah Palin and Joe Biden, said they would reduce the role to simply being an adviser to the president.

Constitutional roles

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Politics of the United States |

|---|

|

Although delegates to the constitutional convention approved establishing the office, with both its executive and senatorial functions, not many understood the office, and so they gave the vice president few duties and little power. Only a few states had an analogous position. Among those that did, New York's constitution provided that "the lieutenant-governor shall, by virtue of his office, be president of the Senate, and, upon an equal division, have a casting voice in their decisions, but not vote on any other occasion". As a result, the vice presidency originally had authority in only a few areas, although constitutional amendments have added or clarified some matters.

President of the Senate

Article I, Section 3, Clause 4 confers upon the vice president the title "President of the Senate", authorizing the vice president to preside over Senate meetings. In this capacity, the vice president is responsible for maintaining order and decorum, recognizing members to speak, and interpreting the Senate's rules, practices, and precedent. With this position also comes the authority to cast a tie-breaking vote. In practice, the number of times vice presidents have exercised this right has varied greatly. Kamala Harris holds the record at 33 votes, followed by John C. Calhoun who had previously held the record at 31 votes; John Adams ranks third with 29. Twelve vice presidents, (aside from recently inaugurated JD Vance), did not cast any tie-breaking votes.

As the framers of the Constitution anticipated that the vice president would not always be available to fulfill this responsibility, the Constitution provides that the Senate may elect a president pro tempore (or "president for a time") in order to maintain the proper ordering of the legislative process. In practice, since the early 20th century, neither the president of the Senate nor the pro tempore regularly presides; instead, the president pro tempore usually delegates the task to other Senate members. Rule XIX, which governs debate, does not authorize the vice president to participate in debate, and grants only to members of the Senate (and, upon appropriate notice, former presidents of the United States) the privilege of addressing the Senate, without granting a similar privilege to the sitting vice president. Thus, Time magazine wrote in 1925, during the tenure of Charles G. Dawes, "once in four years the vice president can make a little speech, and then he is done. For four years he then has to sit in the seat of the silent, attending to speeches ponderous or otherwise, of deliberation or humor."

Presiding over impeachment trials

In their capacity as president of the Senate, the vice president may preside over most impeachment trials of federal officers, although the Constitution does not specifically require it. However, whenever the president of the United States is on trial, the Constitution requires that the chief justice of the United States must preside. This stipulation was designed to avoid the possible conflict of interest in having the vice president preside over the trial for the removal of the one official standing between them and the presidency. In contrast, the Constitution is silent about which federal official would preside were the vice president on trial by the Senate. No vice president has ever been impeached, thus leaving it unclear whether an impeached vice president could, as president of the Senate, preside at their own impeachment trial.

Presiding over electoral vote counts

The Twelfth Amendment provides that the vice president, in their capacity as the president of the Senate, receives the Electoral College votes, and then, in the presence of the Senate and House of Representatives, opens the sealed votes. The votes are counted during a joint session of Congress as prescribed by the Electoral Count Act and the Electoral Count Reform and Presidential Transition Improvement Act. The former specifies that the president of the Senate presides over the joint session, and the latter clarifies the solely ministerial role the president of the Senate serves in the process. The next such joint session will next take place following the 2028 presidential election, on January 6, 2029 (unless Congress sets a different date by law).

In this capacity, four vice presidents have been able to announce their own election to the presidency: John Adams, in 1797, Thomas Jefferson, in 1801, Martin Van Buren, in 1837 and George H. W. Bush, in 1989. Conversely, John C. Breckinridge, in 1861, Richard Nixon, in 1961, Al Gore, in 2001, and Kamala Harris, in 2025, each had to announce their opponent's election victory. In 1969, Vice President Hubert Humphrey would have done so as well, following his 1968 loss to Richard Nixon; however, on the date of the congressional joint session, Humphrey was in Norway attending the funeral of Trygve Lie, the first elected Secretary-General of the United Nations. The president pro tempore, Richard Russell, presided in his absence. On February 8, 1933, Vice President Charles Curtis announced the election victory of his successor, House Speaker John Nance Garner, while Garner was seated next to him on the House dais. Similarly, Walter Mondale, in 1981, Dan Quayle, in 1993, and Mike Pence, in 2021, each had to announce their successor's election victory, following their re-election losses.

Successor to the U.S. president

Article II, Section 1, Clause 6 stipulates that the vice president takes over the "powers and duties" of the presidency in the event of a president's removal, death, resignation, or inability. Even so, it did not clearly state whether the vice president became president or simply acted as president in a case of succession. Debate records from the 1787 Constitutional Convention, along with various participants' later writings on the subject, show that the framers of the Constitution intended that the vice president would temporarily exercise the powers and duties of the office in the event of a president's death, disability or removal, but not actually become the president of the United States in their own right.

This understanding was first tested in 1841, following the death of President William Henry Harrison, only 31 days into his term. Harrison's vice president, John Tyler, asserted that under the Constitution, he had succeeded to the presidency, not just to its powers and duties. He had himself sworn in as president and assumed full presidential powers, refusing to acknowledge documents referring to him as "Acting President". Although some in Congress denounced Tyler's claim as a violation of the Constitution, he adhered to his position. His view ultimately prevailed as both the Senate and House voted to acknowledge him as president. The "Tyler Precedent" that a vice president assumes the full title and role of president upon the death, resignation, or removal from office (via impeachment conviction) of their predecessor was codified through the Twenty-fifth Amendment in 1967. Altogether, nine vice presidents have succeeded to the presidency intra-term. In addition to Tyler, they are Millard Fillmore, Andrew Johnson, Chester A. Arthur, Theodore Roosevelt, Calvin Coolidge, Harry S. Truman, Lyndon B. Johnson, and Gerald Ford. Four of them—Roosevelt, Coolidge, Truman, and Lyndon B. Johnson—were later elected to full terms of their own.

Four sitting vice presidents have been elected president: John Adams in 1796, Thomas Jefferson in 1800, Martin Van Buren in 1836, and George H. W. Bush in 1988. Likewise, two former vice presidents have won the presidency, Richard Nixon in 1968 and Joe Biden in 2020. Also, five incumbent vice presidents lost a presidential election: Breckinridge in 1860, Nixon in 1960, Humphrey in 1968, Gore in 2000, and Harris in 2024. Additionally, former vice president Walter Mondale lost in 1984. In total, 15 vice presidents have become president.

Acting president

Sections 3 and 4 of the Twenty-fifth Amendment provide for situations where the president is temporarily or permanently unable to lead, such as if the president has a surgical procedure, becomes seriously ill or injured, or is otherwise unable to discharge the powers or duties of the presidency. Section 3 deals with self-declared incapacity, and Section 4 addresses incapacity declared by the joint action of the vice president and of a majority of the Cabinet. While Section 4 has never been invoked, Section 3 has been invoked on four occasions by three presidents, first in 1985. When invoked on November 19, 2021, Kamala Harris became the first woman in U.S. history to have presidential powers and duties.

Sections 3 and 4 were added because there was ambiguity in the Article II succession clause regarding a disabled president, including what constituted an "inability", who determined the existence of an inability, and if a vice president became president for the rest of the presidential term in the case of an inability or became merely "acting president". During the 19th century and first half of the 20th century, several presidents experienced periods of severe illness, physical disability or injury, some lasting for weeks or months. During these times, even though the nation needed effective presidential leadership, no vice president wanted to seem like a usurper, and so power was never transferred. After President Dwight D. Eisenhower openly addressed his health issues and made it a point to enter into an agreement with Vice President Richard Nixon that provided for Nixon to act on his behalf if Eisenhower became unable to provide effective presidential leadership (Nixon did informally assume some of the president's duties for several weeks on each of three occasions when Eisenhower was ill), discussions began in Congress about clearing up the Constitution's ambiguity on the subject.

Modern roles

The present-day power of the office flows primarily from formal and informal delegations of authority from the president and Congress. These delegations can vary in significance; for example, the vice president is a statutory member of both the National Security Council and the board of regents of the Smithsonian Institution. The extent of the roles and functions of the vice president depend on the specific relationship between the president and the vice president, but often include tasks such as drafter and spokesperson for the administration's policies, adviser to the president, and being a symbol of American concern or support. The influence of the vice president in these roles depends almost entirely on the characteristics of the particular administration.