American Natural History Museum

The AMNH is a private 501(c)(3) organization. The naturalist Albert S. Bickmore devised the idea for the American Museum of Natural History in 1861, and, after several years of advocacy, the museum opened within Central Park's Arsenal on May 22, 1871. The museum's first purpose-built structure in Theodore Roosevelt Park was designed by Calvert Vaux and J. Wrey Mould and opened on December 22, 1877. Numerous wings have been added over the years, including the main entrance pavilion (named for Theodore Roosevelt) in 1936 and the Rose Center for Earth and Space in 2000.

History

Founding

Early efforts

The naturalist Albert S. Bickmore devised the idea for the American Museum of Natural History in 1861. At the time, he was studying in Cambridge, Massachusetts, at Louis Agassiz's Museum of Comparative Zoology. Observing that many European natural history museums were in populous cities, Bickmore wrote in a biography: "Now New York is our city of greatest wealth and therefore probably the best location for the future museum of natural history for our whole land." For several years, Bickmore lobbied for the establishment of a natural history museum in New York. Upon the end of the American Civil War, Bickmore asked numerous prominent New Yorkers, such as William E. Dodge Jr., to sponsor his museum. Although Dodge himself could not fund the museum at the time, he introduced the naturalist to Theodore Roosevelt Sr., the father of future U.S. president Theodore Roosevelt.

Calls for a natural history museum increased after Barnum's American Museum burned down in 1868. Eighteen prominent New Yorkers wrote a letter to the Central Park Commission that December, requesting the creation of a natural history museum in Central Park. Central Park commissioner Andrew Haswell Green indicated his support for the project in January 1869. A board of trustees was created for the museum. The next month, Bickmore and Joseph Hodges Choate drafted a charter for the museum, which the board of trustees approved without any changes. It was in this charter that the "American Museum of Natural History" name was first used. Bickmore said he wanted the museum's name to reflect his "expectation that our museum will ultimately become the leading institution of its kind in our country", similar to the British Museum. Before the museum was established, Bickmore needed to secure approval from Boss Tweed, leader of the powerful and corrupt Tammany Hall political organization. The legislation to establish the American Museum of Natural History had to be signed by John Thompson Hoffman, the governor of New York, who was associated with Tweed.

Creation and new building

Hoffman signed the legislation creating the museum on April 6, 1869, with John David Wolfe as its first president. Subsequently, the chairman of the AMNH's executive committee asked Green if the museum could use the top two stories of Central Park's Arsenal, and Green approved the request in January 1870. Insect specimens were placed on the lower level of the Arsenal, while stones, fossils, mammals, birds, fish, and reptiles were placed on the upper level. The museum opened within the Arsenal on May 22, 1871. The AMNH became popular in the following years. The Arsenal location had 856,773 visitors in the first nine months of 1876 alone, more than the British Museum had recorded for all of 1874.

Meanwhile, the AMNH's directors had identified Manhattan Square (bounded by Eighth Avenue/Central Park West, 81st Street, Ninth Avenue/Columbus Avenue, and 77th Street) as a site for a permanent structure. Several prominent New Yorkers had raised $500,000 to fund the construction of the new building. The city's park commissioners then reserved Manhattan Square as the site of the permanent museum, and another $200,000 was raised for the building fund. Numerous dignitaries and officials, including U.S. president Ulysses S. Grant, attended the museum's groundbreaking ceremony on June 3, 1874.

The museum opened on December 22, 1877, with a ceremony attended by U.S. president Rutherford B. Hayes. The old exhibits were removed from the Arsenal in 1878, and the AMNH was debt-free by the next year.

19th century

Originally, the AMNH was accessed by a temporary bridge that crossed a ditch, and it was closed during Sundays. The museum's trustees voted in May 1881 to complete the approaches from Central Park, and work began later that year. The landscape changes were nearly complete by mid-1882, and a bridge over Central Park West opened that November. At this point, the AMNH's Manhattan Square building and the Arsenal could not physically fit any more objects, and the existing facilities, such as the 100-seat lecture hall, were insufficient to accommodate demand. The trustees began discussing the possibility of opening the museum on Sundays in May 1885, and the state legislature approved a bill permitting Sunday operations the next year. Despite advocacy from the working class, the trustees opposed Sunday operations because it would be expensive to do so. At the time, the museum was open to the general public on Wednesdays through Saturdays, and it was open exclusively to members on Mondays and Tuesdays. The museum's collections continued to grow during the 1880s, and it hosted various lectures through the 19th century.

With several departments having been crowded out of the original building, New York state legislators introduced bills to expand the AMNH in early 1887; thousands of teachers endorsed the legislation. City parks engineer Montgomery A. Kellogg was directed to prepare plans for landscaping the site. In March 1888, the trustees approved an entrance pavilion at the center of the 77th Street elevation. The New York City Board of Estimate began soliciting bids from general contractors in late 1889. Many of the objects and specimens in the museum's collection could not be displayed until the annex was opened. The original building was refurbished during 1890, and the museum's library was transferred to the west wing that year. The AMNH's trustees considered opening the museum on Sundays by February 1892 and stopped charging admission that July. The museum began Sunday operations in August, and the southern entrance pavilion opened that November. Even with the new wing, there was still not enough space for the museum's collection. The city's Park Board approved a new lecture hall in January 1893, but the hall was postponed that May in favor of a wing extending east on 77th Street. A contract to furnish the east wing was awarded in June 1894.

When the east wing was nearly completed in February 1895, the AMNH's trustees asked state legislators for $200,000 to build a wing extending west on 77th Street. The east wing was still being furnished by August; its ground floor opened that December. The museum's funds and collections continued to grow during this time. A hall of mammals opened within the museum in November 1896. That year, the AMNH received approval to extend the east wing northward along Central Park West, creating an L-shaped structure. Plans for an expanded east wing were approved in June 1897, and a contract was awarded two months later. The museum's director Morris K. Jesup also sponsored worldwide expeditions to obtain objects for the collection. By mid-1898, the west wing, the expanded east wing, and a lecture hall at the center of the museum were underway; however, the project encountered delays due to a lack of city funding. The west and east wings, with several exhibit halls, were nearly complete by late 1899, but the lecture hall had been delayed. A hall dedicated to ancient Mexican art opened that December.

20th century

1900s to 1940s

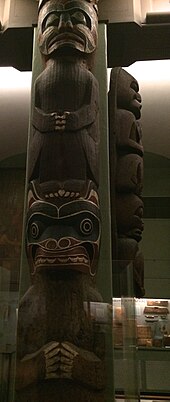

The museum's 1,350-seat lecture hall opened in October 1900, as did the Native American and Mexican halls in the west wing. During the 1900s, the AMNH sponsored several expeditions to grow its collection, including a trip to Mexico, a trip to collect fauna from the Pacific Northwest, a trip to collect art in China, and an expedition to collect rocks in local caves. One such exhibition yielded a brontosaurus skeleton, which was the centerpiece of the dinosaur hall that opened in February 1905.

In the early 1920s, museum president Henry Fairfield Osborn planned a new entrance for the AMNH, which was to contain a memorial to Theodore Roosevelt. Also around that time, the New York state government formed a commission to study the feasibility of a Roosevelt memorial. After a dispute over whether to put the memorial in Albany or in New York City, the government of New York City offered a site next to the AMNH for consideration. The commission rejected a "conventional Greek mausoleum" design, instead opting to design a triumphal arch and hall in a Roman style. In 1925, the AMNH's trustees hosted an architectural design competition, selecting John Russell Pope to design the memorial hall. Construction began in 1929, and the trustees approved final plans the next year. J. Harry McNally was the general contractor. Roosevelt's cousin, U.S. president Franklin D. Roosevelt, dedicated the memorial on January 19, 1936.

1950s to 1990s

The original building was later known as "Wing A". During the 1950s, the top floor was renovated into a library, being redecorated with what Christopher Gray of The New York Times described as "dropped ceilings and the other usual insults". The ten-story Childs Frick Building, which contained the AMNH's fossil collection, was added to the museum in the 1970s.

The architect Kevin Roche and his firm Roche-Dinkeloo have been responsible for the master planning of the museum since the 1990s. Various renovations to both the interior and exterior have been carried out. Renovations to the Dinosaur Hall were undertaken beginning in 1991, and Roche-Dinkeloo designed the eight-story AMNH Library in 1992. The museum's Rose Center for Earth and Space was completed in 2000.

21st century

In 2001, the museum's lecture hall was renamed the Samuel J. and Ethel LeFrak Theater, after Samuel J. LeFrak donated US$8 million to the AMNH. The museum's south facade, spanning 77th Street from Central Park West to Columbus Avenue, was cleaned and repaired, re-emerging in 2009. Steven Reichl, a spokesman for the museum, said that work would include restoring 650 black-cherry window frames and stone repairs. The museum's consultant on the latest renovation was Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates, Inc., an architectural and engineering firm with headquarters in Northbrook, Illinois. The museum also restored the mural in Roosevelt Memorial Hall in 2010.

Gilder Center

In 2014, the museum published plans for a $325 million, 195,000 sq ft (18,100 m) annex, the Richard Gilder Center for Science, Education, and Innovation, on the Columbus Avenue side.

On October 11, 2016, the Landmarks Preservation Commission unanimously approved the expansion. Construction of the Gilder Center, which was expected to break ground the next year following design development and Environmental Impact Statement stages, would entail demolition of three museum buildings built between 1874 and 1935. The museum filed plans for the expansion in August 2017, but due to community opposition, construction did not start until June 2019.

On May 4, 2023, the Gilder Center opened, and the museum had 1.5 million visitors over the next three months.

Native remains

In late 2023, the museum announced that it would stop displaying human remains from its collection. Despite the 1990 passage of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), as late as 2023, the AMNH held an estimated 1,900 Native American remains that had not been repatriated.

After the act was revised in January 2024, the AMNH's Eastern Woodlands and Great Plains halls were closed because the museum would have needed permission to display all of the artifacts in the halls. The museum agreed to repatriate the remains that July.

Original structure

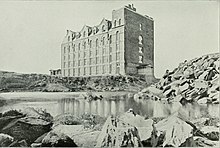

The original Victorian Gothic building was designed by Calvert Vaux and J. Wrey Mould, both already closely identified with the architecture of Central Park. Vaux and Mould's original plan was intended to complement the Metropolitan Museum of Art on the opposite side of Central Park. The original building, as constructed, was at the center of the 77th Street frontage and measured 199 by 66 feet (61 by 20 m) across; it featured a gallery measuring 112 feet (34 m) long200 ft (61 m) tall. This gallery contained a raised basement, three stories of exhibits, Venetian Gothic arches, and an attic with dormers and a slate roof. The rear of the gallery included two towers: one containing a stairwell and the other containing curators' rooms. The original structure still exists but is hidden from view by the many buildings in the complex that today occupy most of Manhattan Square. The museum remains accessible through its 77th Street foyer, which has since been renamed the Grand Gallery.

The full plan called for twelve pavilions similar in design to the original building. Eight pavilions would have been arranged as the sides of a square, while the remaining four would be perpendicular to each other in the interior of the square. There were to be eight towers along the perimeter of the square, as well as a 120 ft-wide (37 m) dome in the center, at the intersection of the four interior pavilions. In each pavilion, there was to be a ground floor; the second floor was to contain a gallery; the third floor was to exhibit specimens; and the fourth floor was to be used for research. Upon the intended completion of the master plan, the museum would measure 850 ft (260 m) from north to south and 650 ft (200 m) from west to east, including projections from the square. The finished structure, with a ground area of over 18 acres (7.3 ha), would have been the largest building in North America, as well as the largest museum building in the world. The master plan was never fully realized; by 2015, the museum consisted of 25 separate buildings that were poorly connected.

The original building was soon eclipsed by the west and east wings of the southern frontage, designed by J. Cleaveland Cady as a brownstone neo-Romanesque structure. It extends 700 ft (210 m) along West 77th Street, with corner towers 150 ft (46 m) tall. Its pink brownstone and granite, similar to that found at Grindstone Island in the St. Lawrence River, came from quarries at Picton Island, New York. The southern wing contains several halls ranging in size from 60 by 110 feet (18 m × 34 m) to 30 ft × 125 ft (9.1 m × 38.1 m). At the ends of either wings are rounded turret-like towers.

New York State Memorial to Theodore Roosevelt

The main entrance hall on Central Park West is formally known as the New York State Memorial to Theodore Roosevelt. Completed by John Russell Pope in 1936, it is an over-scaled Beaux-Arts monument to former U.S. president Theodore Roosevelt. The hall was originally supposed to have formed one end of an "Intermuseum Promenade" through Central Park, connecting with the Metropolitan Museum of Art to the east, but the promenade was never completed.

The memorial hall has a pink-granite facade, which is modeled after Roman arches. In front of the hall on Central Park West is a terrace measuring 350 ft (110 m) long, as well as a series of steps. The main entrance consists of an arch measuring 60 ft (18 m) high. The underside of the arch is a coffered granite vestibule, which leads to a bronze, glass, and marble screen. On either side of the arch are niches that contain sculptures of a bison and a bear. It is flanked by two pairs of columns, which are topped by figures of American explorers John James Audubon, Daniel Boone, Meriwether Lewis, and William Clark. These figures were sculpted by James Earle Fraser and are about 30 ft (9.1 m) high. In the attic above the main archway, there is an inscription describing Roosevelt's accomplishments. The words "Truth", "Knowledge", and "Vision" are carved into the entablature under this inscription.

Fraser also designed an equestrian statue of Theodore Roosevelt, flanked by a Native American and an African American, which originally stood outside the memorial hall. In the 21st century, the statue generated controversy due to its subordinate depiction of these figures behind Roosevelt. This prompted AMNH officials to announce in 2020 that they would remove the statue. The statue was removed in January 2022 and will be on a long-term loan to the Theodore Roosevelt Presidential Library in North Dakota.

The interior of the Memorial Hall measures 67 by 120 ft (20 by 37 m) across, with a barrel-vaulted ceiling measuring 100 ft (30 m) tall. The ceiling contains octagonal coffers, while the floors are made of mosaic marble tiles. The lowest 9 ft (2.7 m) of the walls are wainscoted in marble, above which the walls of the memorial hall are made of limestone. The top of each wall contains a marble band and a Corinthian entablature. Each of the Memorial Hall's four sides contains two red-marble columns, each measuring 48 ft (15 m) tall and rising from a Botticino marble pedestal. There are rounded windows at clerestory level on the north and south walls. William Andrew MacKay designed three 62 ft-wide (19 m) murals depicting important events in Roosevelt's life: the construction of the Panama Canal on the north wall, African exploration on the west wall, and the Treaty of Portsmouth on the south wall. The east and west walls, contain four quotes from Roosevelt under the headings "Nature", "Manhood", "Youth", and "The State".

The Memorial Hall originally connected to various classrooms, exhibition rooms, and a 600-person auditorium. Directly underneath the Memorial Hall is an entrance to the 81st Street–Museum of Natural History station. Today, the hall connects to the Akeley Hall of African Mammals and the Hall of Asian Mammals. The Memorial Hall contains four exhibits that describe Theodore Roosevelt's conservation activities in his youth, early adulthood, U.S. presidency, and post-presidency.

Mammal halls

Old World mammals

Akeley Hall of African Mammals

Named after taxidermist Carl Akeley, the Akeley Hall of African Mammals is a two-story hall on the second floor, directly west of the Theodore Roosevelt Memorial Hall. It connects to the Hall of African Peoples to the west. The Hall of African Mammals' 28 dioramas depict in meticulous detail the great range of ecosystems found in Africa and the mammals endemic to them. The centerpiece of the hall is a herd of eight African elephants in a characteristic 'alarmed' formation. Though the mammals are typically the main feature in the dioramas, birds and flora of the regions are occasionally featured as well. The hall in its current form was completed in 1936.

The Hall of African Mammals was first proposed to the museum by Carl Akeley around 1909; he proposed 40 dioramas featuring the rapidly vanishing landscapes and animals of Africa. Daniel Pomeroy, a trustee of the museum and partner at J.P. Morgan & Co., offered investors the opportunity to accompany the museum's expeditions in Africa in exchange for funding. Akeley began collecting specimens for the hall as early as 1909, famously encountering Theodore Roosevelt in the midst of the Smithsonian-Roosevelt African expedition. On these early expeditions, Akeley was accompanied by his former apprentice in taxidermy, James L. Clark, and artist, William R. Leigh. When Akeley returned to Africa to collect gorillas for the hall's first diorama, Clark remained behind and began scouring the country for artists to create the backgrounds. The eventual appearance of the first habitat groups impacted the design of other diorama halls, including Birds of the World, the Hall of North American Mammals, the Vernay Hall of Southeast Asian Mammals, and the Hall of Oceanic Life.

After Akeley's unexpected death during the Eastman-Pomeroy expedition in 1926, responsibility of the hall's completion fell to James L. Clark, who hired architectural artist James Perry Wilson in 1933 to assist Leigh in the painting of backgrounds. Wilson made many improvements on Leigh's techniques, including a range of methods to minimize the distortion caused by the dioramas' curved walls. In 1936, William Durant Campbell, a wealthy board member with a desire to see Africa, offered to fund several dioramas if allowed to obtain the specimens himself. Clark agreed to this arrangement, resulting in the acquisition of numerous large specimens. Kane joined Leigh, Wilson, and several other artists in completing the hall's remaining dioramas. Though construction of the hall was completed in 1936, the dioramas gradually opened between the mid-1920s and early 1940s.

Hall of Asian Mammals

The Hall of Asian Mammals, sometimes referred to as the Vernay-Faunthorpe Hall of Asian Mammals, is directly south of the Theodore Roosevelt Memorial Hall. It contains 8 complete dioramas, 4 partial dioramas, and 6 habitat groups of mammals and locations from India, Nepal, Burma, and Malaysia. The hall opened in 1930 and, similar to the Akeley Hall of African Mammals, is centered around 2 Asian elephants. At one point, a giant panda and Siberian tiger were also part of the Hall's collection, originally intended to be part of an adjoining Hall of North Asian Mammals (planned in the current location of Stout Hall of Asian Peoples). These specimens can currently be seen in the Hall of Biodiversity.

Specimens for the Hall of Asian Mammals were collected over six expeditions led by British-born antiques dealer Arthur S. Vernay and Col. John Faunthorpe (as noted by stylized plaques at both entrances). The expeditions were funded entirely by Vernay, who characterized the expense as a British tribute to American involvement in World War I. The first Vernay-Faunthorpe expedition took place in 1922, when many of the animals Vernay was seeking, such as the Sumatran rhinoceros and Asiatic lion, were facing the possibility of extinction. Vernay made many appeals to regional authorities to obtain hunting permits; in later museum-related expeditions headed by Vernay, these appeals helped the museum gain access to areas previously restricted to foreign visitors. Artist Clarence C. Rosenkranz accompanied the Vernay-Faunthorpe expeditions as field artist and painted the majority of the diorama backgrounds in the hall. These expeditions were also well documented in both photo and video, with enough footage of the first expedition to create a feature-length film, Hunting Tigers in India (1929).

| Species and Locations Represented in the Hall of Asian Mammals | ||

|---|---|---|

| India (Assam) | Hoolock gibbon | |

| – | Thamin | |

| (Awadh) | Sambar | Barasingha |

| – | Chital | |

| (Bhopal) | Sambar | Dhole (listed as wild dog) |

| (Bikanir) | Blackbuck | Chinkara |

| (Biligiriranga Hills, listed as Kallegal Range) | Leopard | |

| (Mysore) | Gaur | Indian roller |

| (Manas River) | Wild water buffalo | |

| Nepal (Base of the Himalayas) | Tiger | |

| (Morang) | Indian rhinoceros | |

| Burma (Rangoon) | Banteng | |

| Habitat groups | ||

| Sloth bear | ||

| Four-horned antelope | Smooth-coated otter | |

| Muntjac | Spotted chevrotain | |

| Sumatran rhinoceros | ||

| Hog deer | Indian wild boar | |

| Asiatic lion |

New World mammals

Bernard Family Hall of North American Mammals

The Bernard Family Hall of North American Mammals is on the first floor, directly west of the Theodore Roosevelt Memorial Hall. features 43 dioramas of various mammals of the American continent, north of tropical Mexico. Each diorama places focus on a particular species, ranging from the largest megafauna to the smaller rodents and carnivorans. Notable dioramas include the Alaskan brown bears looking at a salmon after they scared off an otter, a pair of wolves, a pair of Sonoran jaguars, and dueling bull Alaska moose.

The Hall of North American Mammals opened in 1942 with only ten dioramas. Another 16 dioramas were added in 1963. A massive restoration project began in late 2011 following a large donation from Jill and Lewis Bernard. In October 2012 the hall was reopened as the Bernard Hall of North American Mammals.

Hall of Small Mammals

The Hall of Small Mammals is an offshoot of the Bernard Family Hall of North American Mammals, directly to the west of the latter. There are several small dioramas featuring small mammals found throughout North America, including collared peccaries, Abert's squirrel, and a wolverine.

Birds, reptiles, and amphibian halls

Sanford Hall of North American Birds

The Sanford Hall of North American birds is a one-story hall on the third floor, between the Hall of Primates and Akeley Hall's second level. There are over 20 dioramas depicting birds from across North America in their native habitats. At the far end of the hall are two large murals by ornithologist and artist Louis Agassiz Fuertes. The hall also has display cases devoted to large collections of warblers, owls, and raptors.

Conceived by museum ornithologist Frank Chapman, the Hall is named for Chapman's friend and amateur ornithologist Leonard C. Sanford, who partially funded the hall and also donated the entirety of his own bird specimen collection to the museum. Construction began on the hall's dioramas as early as 1902, and the dioramas opened in 1909. They were the first to be exhibited in the museum and are the oldest still on display. The hall was refurbished in 1962.

Although Chapman was not the first to create museum dioramas, he was the first to bring artists into the field with him in the hopes of capturing a specific location at a specific time. In contrast to the dramatic scenes that Akeley created for the African Hall, Chapman wanted his dioramas to evoke a scientific realism, ultimately serving as a historical record of habitats and species facing a high probability of extinction. Each of Chapman's dioramas depicted a species, their nests, and 4 ft (1.2 m) of the surrounding habitat in each direction.

Hall of Birds of the World

The Hall of Birds of the World is on the south side of the second floor. The global diversity of bird species is exhibited in this hall. 12 dioramas showcase various ecosystems around the world and provide a sample of the varieties of birds that live there. Example dioramas include South Georgia featuring king penguins and skuas, the East African plains featuring secretarybirds and bustards, and the Australian outback featuring honeyeaters, cockatoos, and kookaburras.

Whitney Memorial Hall of Oceanic Birds

The Whitney Memorial Wing, originally named after Harry Payne Whitney and comprising 750,000 birds, opened in 1939. Later known as the Hall of Oceanic Birds, it was completed and dedicated in 1953. It was founded by Frank Chapman and Leonard C. Sanford, originally museum volunteers, who had gone forward with creation of a hall to feature birds of the Pacific islands. The hall was designed as a completely immersive collection of dioramas, including a circular display featuring birds-of-paradise. In 1998, the Butterfly Conservatory was installed inside the hall.

Hall of Reptiles and Amphibians

The Hall of Reptiles and Amphibians is near the southeast corner of the third floor. It serves as an introduction to herpetology, with many exhibits detailing reptile evolution, anatomy, diversity, reproduction, and behavior. Notable exhibits include a Komodo dragon group, an American alligator, Lonesome George, the last Pinta Island tortoise, and poison dart frogs.

In 1926, W. Douglas Burden, F.J. Defosse, and Emmett Reid Dunn collected specimens of the Komodo Dragon for the museum. Burden's chapter "The Komodo Dragon", in Look to the Wilderness, describes the expedition, the habitat, and the behavior of the dragon. The hall opened in 1927 and was rebuilt from 1969 to 1977 at a cost of $1.3 million.

Biodiversity and environmental halls

Hall of Biodiversity

The Hall of Biodiversity is underneath the Theodore Roosevelt Memorial Hall. It opened in May 1998. The hall primarily contains exhibits and objects highlighting the concept of biodiversity, the interactions between living organisms, and the negative impacts of extinction on biodiversity. The hall includes a 2,500 sq ft (230 m) diorama depicting the Dzanga-Sangha Special Reserve rainforest with over 160 animal and plant species. The diorama shows the rainforest in three states: pristine, altered by human activity, and destroyed by human activity. Another attraction in the hall is "The Spectrum of Habitats", a video wall displaying footage of nine ecosystems. There is a "Transformation Wall", containing information and stories detailing changes to biodiversity, and a "Solutions Wall", containing suggestions on how to increase biodiversity.

Hall of North American Forests

The Hall of North American Forests is a one-story hall on the museum's first floor in between the Theodore Roosevelt Memorial Hall and the Warburg Hall of New York State Environments. It contains ten dioramas depicting a range of forest types from across North America as well as several displays on forest conservation and tree health. The hall was constructed under the guidance of botanist Henry K. Svenson and opened in 1958. Each diorama specifically lists both the location and exact time of year depicted. Trees and plants featured in the dioramas are constructed of a combination of art supplies and actual bark and other specimens collected in the field. The entrance to the hall features a cross section from the Mark Twain Tree, 1,400-year-old sequoia taken from the King's River grove on the west flank of the Sierra Mountains in 1891.

| Locations Represented in the Hall of North American Forests | |

|---|---|

| Oak-Hickory Forest in late August | Ozark Plateau |

| Northern Spruce-Fir in mid-August | Lake Nipigon |

| Jeffrey Pine Forest in early June | Inyo National Forest |

| Olympic Rain Forest in mid-June | Quinault Rainforest |

| Timberline of the Northern Rocky Mountains in mid-July | Logan Pass |

| Pinyon-Juniper Woodland in early October | Colorado National Monument |

| Giant Cactus Forest in mid-April | Saguaro National Park |

| Southeastern Coastal Plain Forest in mid-March | Coosawhatchie River, South Carolina |

| Mixed Deciduous Forest in late April | Great Smoky Mountains National Park |

| Early October in Southern New Hampshire | Lake Sunapee |

Warburg Hall of New York State Environments

Warburg Hall of New York State Environments is a one-story hall on the museum's ground floor in between the Hall of North American Forests and the Grand Hall. Based on the town of Pine Plains in Dutchess County, New York, the hall gives a multi-faceted presentation of the eco-systems typical of New York. Aspects covered include soil types, seasonal changes, and the impact of both humans and nonhuman animals on the environment. It is named for the German-American philanthropist Felix M. Warburg and opened on May 14, 1951, as the Warburg Memorial Hall of General Ecology. It has changed little since and is now frequently regarded for its retro-modern styling.

Milstein Hall of Ocean Life

The Milstein Hall of Ocean Life is in the southeastern quadrant of the first floor, west of the Hall of Biodiversity. It focuses on marine biology, botany and marine conservation. The center of the hall contains a 94 ft (29 m)-long blue whale model. The upper level of the hall exhibits the vast array of ecosystems present in the ocean. Dioramas compare and contrast the life in these different settings including kelp forests, mangroves, coral reefs, the bathypelagic, among others. It attempts to show how vast and varied the oceans are while encouraging common themes throughout. The lower half of the hall consists of 15 large dioramas of larger marine organisms. It is on this level that the famous "Squid and the Whale" diorama sits, depicting a hypothetical fight between the two creatures. Other notable exhibits in this hall include the two-level Andros Coral Reef Diorama.

In 1910, museum president Henry F. Osborn proposed the construction of a large building in the museum's southeast courtyard to house a new Hall of Ocean Life in which "models and skeletons of whales" would be exhibited. The hall opened in 1924 and was renovated in 1962. In 1969, a renovation gave the hall a more explicit focus on oceanic megafauna, including the addition of a lifelike blue whale model to replace a popular steel and papier-mâché whale model that had hung in the Biology of Mammals hall. Richard Van Gelder oversaw the creation of the hall in its current incarnation. The hall was renovated once again in 2003, this time with environmentalism and conservation being the main focal points, and was renamed after developer Paul Milstein and AMNH board member Irma Milstein. The 2003 renovation included refurbishment of the famous blue whale, suspended high above the 19,000 sq ft (1,800 m) exhibit floor; updates to the 1930s and 1960s dioramas; and electronic displays.

Human origins and cultural halls

Cultural halls

Stout Hall of Asian Peoples

The Stout Hall of Asian Peoples is a one-story hall on the museum's second floor in between the Hall of Asian Mammals and Birds of the World. It is named for Gardner D. Stout, a former president of the museum, and was primarily organized by Walter A. Fairservis, a longtime museum archaeologist. Opened in 1980, Stout Hall is the museum's largest anthropological hall and contains artifacts acquired by the museum between 1869 and the mid-1970s. Many famous expeditions sponsored by the museum are associated with the artifacts in the hall, including the Roy Chapman Andrews expeditions in Central Asia and the Vernay-Hopwood Chindwin expedition.

Stout Hall has two sections: Ancient Eurasia, a small section devoted to the evolution of human civilization in Eurasia, and Traditional Asia, a much larger section containing cultural artifacts from across the Asian continent. The latter section is organized to geographically correspond with two major trade routes of the Silk Road. Like many of the museum's exhibition halls, the artifacts in Stout Hall are presented in a variety of ways including exhibits, miniature dioramas, and five full-scale dioramas. Notable exhibits in the Ancient Eurasian section include reproductions from the archaeological sites of Teshik-Tash and Çatalhöyük, as well as a full size replica of a Hammurabi Stele. The Traditional Asia section contains areas devoted to major Asian countries, such as Japan, China, Tibet, and India, while also including a vast array of smaller Asian tribes including the Ainu, Semai, and Yakut.

-

A forced perspective, miniature diorama of Isfahan

-

A Yakut shaman performs a healing rite in this diorama

-

A range of costumes worn by women in Islamic Asia