Atlantic

Through its separation of Afro-Eurasia from the Americas, the Atlantic Ocean has played a central role in the development of human society, globalization, and the histories of many nations. While the Norse were the first known humans to cross the Atlantic, it was the expedition of Christopher Columbus in 1492 that proved to be the most consequential. Columbus' expedition ushered in an age of exploration and colonization of the Americas by European powers, most notably Portugal, Spain, France, and the United Kingdom. From the 16th to 19th centuries, the Atlantic Ocean was the center of both an eponymous slave trade and the Columbian exchange while occasionally hosting naval battles. Such naval battles, as well as growing trade from regional American powers like the United States and Brazil, both increased in degree during the early 20th century, and while no major military conflicts have taken place in the Atlantic recently, the ocean remains a core component of trade around the world.

The Atlantic Ocean occupies an elongated, S-shaped basin extending longitudinally between Europe and Africa to the east, and the Americas to the west. As one component of the interconnected World Ocean, it is connected in the north to the Arctic Ocean, to the Pacific Ocean in the southwest, the Indian Ocean in the southeast, and the Southern Ocean in the south. Other definitions describe the Atlantic as extending southward to Antarctica. The Atlantic Ocean is divided in two parts, the northern and southern Atlantic, by the Equator.

Toponymy

The oldest known mentions of an "Atlantic" sea come from Stesichorus around mid-sixth century BC (Sch. A. R. 1. 211): Atlantikôi pelágei (Ancient Greek: Ἀτλαντικῷ πελάγει, 'the Atlantic sea', etym. 'Sea of Atlas') and in The Histories of Herodotus around 450 BC (Hdt. 1.202.4): Atlantis thalassa (Ancient Greek: Ἀτλαντὶς θάλασσα, 'Sea of Atlas' or 'the Atlantic sea') where the name refers to "the sea beyond the pillars of Heracles" which is said to be part of the sea that surrounds all land. In these uses, the name refers to Atlas, the Titan in Greek mythology, who supported the heavens and who later appeared as a frontispiece in medieval maps and also lent his name to modern atlases. On the other hand, to early Greek sailors and in ancient Greek mythological literature such as the Iliad and the Odyssey, this all-encompassing ocean was instead known as Oceanus, the gigantic river that encircled the world; in contrast to the enclosed seas well known to the Greeks: the Mediterranean and the Black Sea. In contrast, the term "Atlantic" originally referred specifically to the Atlas Mountains in Morocco and the sea off the Strait of Gibraltar and the West African coast.

The term "Aethiopian Ocean", derived from Ancient Ethiopia, was applied to the southern Atlantic as late as the mid-19th century. During the Age of Discovery, the Atlantic was also known to English cartographers as the Great Western Ocean.

The pond is a term often used by British and American speakers in reference to the northern Atlantic Ocean, as a form of meiosis, or ironic understatement. It is used mostly when referring to events or circumstances "on this side of the pond" or "on the other side of the pond" or "across the pond", rather than to discuss the ocean itself. The term dates to 1640, first appearing in print in a pamphlet released during the reign of Charles I, and reproduced in 1869 in Nehemiah Wallington's Historical Notices of Events Occurring Chiefly in The Reign of Charles I, where "great Pond" is used in reference to the Atlantic Ocean by Francis Windebank, Charles I's Secretary of State.

Extent and data

The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) defined the limits of the oceans and seas in 1953, but some of these definitions have been revised since then and some are not recognized by various authorities, institutions, and countries, for example the CIA World Factbook. Correspondingly, the extent and number of oceans and seas vary.

The Atlantic Ocean is bounded on the west by North and South America. It connects to the Arctic Ocean through the Labrador Sea, Denmark Strait, Greenland Sea, Norwegian Sea and Barents Sea with the northern divider passing through Iceland and Svalbard. To the east, the boundaries of the ocean proper are Europe and Africa: the Strait of Gibraltar (where it connects with the Mediterranean Sea – one of its marginal seas – and, in turn, the Black Sea, both of which also touch upon Asia).

In the southeast, the Atlantic merges into the Indian Ocean. The 20° East meridian, running south from Cape Agulhas to Antarctica defines its border. In the 1953 definition it extends south to Antarctica, while in later maps it is bounded at the 60° parallel by the Southern Ocean.

The Atlantic has irregular coasts indented by numerous bays, gulfs and seas. These include the Baltic Sea, Black Sea, Caribbean Sea, Davis Strait, Denmark Strait, part of the Drake Passage, Gulf of Mexico, Labrador Sea, Mediterranean Sea, North Sea, Norwegian Sea, almost all of the Scotia Sea, and other tributary water bodies. Including these marginal seas the coast line of the Atlantic measures 111,866 km (69,510 mi) compared to 135,663 km (84,297 mi) for the Pacific.

Including its marginal seas, the Atlantic covers an area of 106,460,000 km (41,100,000 sq mi) or 23.5% of the global ocean and has a volume of 310,410,900 km (74,471,500 cu mi) or 23.3% of the total volume of the Earth's oceans. Excluding its marginal seas, the Atlantic covers 81,760,000 km (31,570,000 sq mi) and has a volume of 305,811,900 km (73,368,200 cu mi). The North Atlantic covers 41,490,000 km (16,020,000 sq mi) (11.5%) and the South Atlantic 40,270,000 km (15,550,000 sq mi) (11.1%). The average depth is 3,646 m (11,962 ft) and the maximum depth, the Milwaukee Deep in the Puerto Rico Trench, is 8,376 m (27,480 ft).

Biggest seas in Atlantic Ocean

Top large seas:

- Sargasso Sea – 3.5 million km

- Caribbean Sea – 2.754 million km

- Mediterranean Sea – 2.510 million km

- Gulf of Guinea – 2.35 million km

- Gulf of Mexico – 1.550 million km

- Norwegian Sea – 1.383 million km

- Greenland Sea – 1.205 million km

- Argentine Sea – 1 million km

- Labrador Sea – 841,000 km

- Irminger Sea – 780,000 km

- Baffin Bay – 689,000 km

- North Sea – 575,000 km

- Black Sea – 436,000 km

- Baltic Sea – 377,000 km

- Libyan Sea – 350,000 km

- Levantine Sea – 320,000 km

- Celtic Sea – 300,000 km

- Tyrrhenian Sea – 275,000 km

- Gulf of Saint Lawrence – 226,000 km

- Bay of Biscay – 223,000 km

- Aegean Sea – 214,000 km

- Ionian Sea – 169,000 km

- Balearic Sea – 150,000 km

- Adriatic Sea – 138,000 km

- Gulf of Bothnia – 116,300 km

- Sea of Crete – 95,000 km

- Gulf of Maine – 93,000 km

- Ligurian Sea – 80,000 km

- English Channel – 75,000 km

- James Bay – 68,300 km

- Bothnian Sea – 66,000 km

- Gulf of Sidra – 57,000 km

- Sea of the Hebrides – 47,000 km

- Irish Sea – 46,000 km

- Sea of Azov – 39,000 km

- Bothnian Bay – 36,800 km

- Gulf of Venezuela – 17,840 km

- Bay of Campeche – 16,000 km

- Gulf of Lion – 15,000 km

- Sea of Marmara – 11,350 km

- Wadden Sea – 10,000 km

- Archipelago Sea – 8,300 km

Bathymetry

The bathymetry of the Atlantic is dominated by a submarine mountain range called the Mid-Atlantic Ridge (MAR). It runs from 87°N or 300 km (190 mi) south of the North Pole to the subantarctic Bouvet Island at 54°S. Expeditions to explore the bathymertry of the Atlantic include the Challenger expedition and the German Meteor expedition; as of 2001, Columbia University's Lamont–Doherty Earth Observatory and the United States Navy Hydrographic Office conduct research on the ocean.

Mid-Atlantic Ridge

The MAR divides the Atlantic longitudinally into two halves, in each of which a series of basins are delimited by secondary, transverse ridges. The MAR reaches above 2,000 m (6,600 ft) along most of its length, but is interrupted by larger transform faults at two places: the Romanche Trench near the Equator and the Gibbs fracture zone at 53°N. The MAR is a barrier for bottom water, but at these two transform faults deep water currents can pass from one side to the other.

The MAR rises 2–3 km (1.2–1.9 mi) above the surrounding ocean floor and its rift valley is the divergent boundary between the North American and Eurasian plates in the North Atlantic and the South American and African plates in the South Atlantic. The MAR produces basaltic volcanoes in Eyjafjallajökull, Iceland, and pillow lava on the ocean floor. The depth of water at the apex of the ridge is less than 2,700 m (1,500 fathoms; 8,900 ft) in most places, while the bottom of the ridge is three times as deep.

The MAR is intersected by two perpendicular ridges: the Azores–Gibraltar transform fault, the boundary between the Nubian and Eurasian plates, intersects the MAR at the Azores triple junction, on either side of the Azores microplate, near the 40°N. A much vaguer, nameless boundary, between the North American and South American plates, intersects the MAR near or just north of the Fifteen-Twenty fracture zone, approximately at 16°N.

In the 1870s, the Challenger expedition discovered parts of what is now known as the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, or:

An elevated ridge rising to an average height of about 1,900 fathoms [3,500 m; 11,400 ft] below the surface traverses the basins of the North and South Atlantic in a meridianal direction from Cape Farewell, probably its far south at least as Gough Island, following roughly the outlines of the coasts of the Old and the New Worlds.

The remainder of the ridge was discovered in the 1920s by the German Meteor expedition using echo-sounding equipment. The exploration of the MAR in the 1950s led to the general acceptance of seafloor spreading and plate tectonics.

Most of the MAR runs under water but where it reaches the surfaces it has produced volcanic islands. While nine of these have collectively been nominated a World Heritage Site for their geological value, four of them are considered of "Outstanding Universal Value" based on their cultural and natural criteria: Þingvellir, Iceland; Landscape of the Pico Island Vineyard Culture, Portugal; Gough and Inaccessible Islands, United Kingdom; and Brazilian Atlantic Islands: Fernando de Noronha and Atol das Rocas Reserves, Brazil.

Ocean floor

Continental shelves in the Atlantic are wide off Newfoundland, southernmost South America, and northeastern Europe. In the western Atlantic carbonate platforms dominate large areas, for example, the Blake Plateau and Bermuda Rise. The Atlantic is surrounded by passive margins except at a few locations where active margins form deep trenches: the Puerto Rico Trench (8,376 m or 27,480 ft maximum depth) in the western Atlantic and South Sandwich Trench (8,264 m or 27,113 ft) in the South Atlantic. There are numerous submarine canyons off northeastern North America, western Europe, and northwestern Africa. Some of these canyons extend along the continental rises and farther into the abyssal plains as deep-sea channels.

In 1922, a historic moment in cartography and oceanography occurred. The USS Stewart used a Navy Sonic Depth Finder to draw a continuous map across the bed of the Atlantic. This involved little guesswork because the idea of sonar is straightforward with pulses being sent from the vessel, which bounce off the ocean floor, then return to the vessel. The deep ocean floor is thought to be fairly flat with occasional deeps, abyssal plains, trenches, seamounts, basins, plateaus, canyons, and some guyots. Various shelves along the margins of the continents constitute about 11% of the bottom topography with few deep channels cut across the continental rise.

The mean depth between 60°N and 60°S is 3,730 m (12,240 ft), or close to the average for the global ocean, with a modal depth between 4,000 and 5,000 m (13,000 and 16,000 ft).

In the South Atlantic the Walvis Ridge and Rio Grande Rise form barriers to ocean currents. The Laurentian Abyss is found off the eastern coast of Canada.

Water characteristics

Surface water temperatures, which vary with latitude, current systems, and season and reflect the latitudinal distribution of solar energy, range from below −2 °C (28 °F) to over 30 °C (86 °F). Maximum temperatures occur north of the equator, and minimum values are found in the polar regions. In the middle latitudes, the area of maximum temperature variations, values may vary by 7–8 °C (13–14 °F).

From October to June the surface is usually covered with sea ice in the Labrador Sea, Denmark Strait, and Baltic Sea.

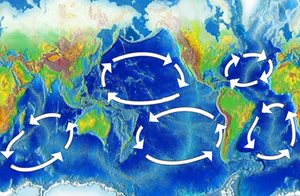

The Coriolis effect circulates North Atlantic water in a clockwise direction, whereas South Atlantic water circulates counter-clockwise. The south tides in the Atlantic Ocean are semi-diurnal; that is, two high tides occur every 24 lunar hours. In latitudes above 40° North some east–west oscillation, known as the North Atlantic oscillation, occurs.

Salinity

On average, the Atlantic is the saltiest major ocean; surface water salinity in the open ocean ranges from 33 to 37 parts per thousand (3.3–3.7%) by mass and varies with latitude and season. Evaporation, precipitation, river inflow and sea ice melting influence surface salinity values. Although the lowest salinity values are just north of the equator (because of heavy tropical rainfall), in general, the lowest values are in the high latitudes and along coasts where large rivers enter. Maximum salinity values occur at about 25° north and south, in subtropical regions with low rainfall and high evaporation.

The high surface salinity in the Atlantic, on which the Atlantic thermohaline circulation is dependent, is maintained by two processes: the Agulhas Leakage/Rings, which brings salty Indian Ocean waters into the South Atlantic, and the "Atmospheric Bridge", which evaporates subtropical Atlantic waters and exports it to the Pacific.

Water masses

| Water mass | Temperature | Salinity |

|---|---|---|

| Upper waters (0–500 m or 0–1,600 ft) | ||

| Atlantic Subarctic Upper Water (ASUW) |

0.0–4.0 °C | 34.0–35.0 |

| Western North Atlantic Central Water (WNACW) |

7.0–20 °C | 35.0–36.7 |

| Eastern North Atlantic Central Water (ENACW) |

8.0–18.0 °C | 35.2–36.7 |

| South Atlantic Central Water (SACW) |

5.0–18.0 °C | 34.3–35.8 |

| Intermediate waters (500–1,500 m or 1,600–4,900 ft) | ||

| Western Atlantic Subarctic Intermediate Water (WASIW) |

3.0–9.0 °C | 34.0–35.1 |

| Eastern Atlantic Subarctic Intermediate Water (EASIW) |

3.0–9.0 °C | 34.4–35.3 |

| Mediterranean Water (MW) | 2.6–11.0 °C | 35.0–36.2 |

| Arctic Intermediate Water (AIW) | −1.5–3.0 °C | 34.7–34.9 |

| Deep and abyssal waters (1,500 m–bottom or 4,900 ft–bottom) | ||

| North Atlantic Deep Water (NADW) |

1.5–4.0 °C | 34.8–35.0 |

| Antarctic Bottom Water (AABW) | −0.9–1.7 °C | 34.6–34.7 |

| Arctic Bottom Water (ABW) | −1.8 to −0.5 °C | 34.9–34.9 |

The Atlantic Ocean consists of four major, upper water masses with distinct temperature and salinity. The Atlantic subarctic upper water in the northernmost North Atlantic is the source for subarctic intermediate water and North Atlantic intermediate water. North Atlantic central water can be divided into the eastern and western North Atlantic central water since the western part is strongly affected by the Gulf Stream and therefore the upper layer is closer to underlying fresher subpolar intermediate water. The eastern water is saltier because of its proximity to Mediterranean water. North Atlantic central water flows into South Atlantic central water at 15°N.

There are five intermediate waters: four low-salinity waters formed at subpolar latitudes and one high-salinity formed through evaporation. Arctic intermediate water flows from the north to become the source for North Atlantic deep water, south of the Greenland-Scotland sill. These two intermediate waters have different salinity in the western and eastern basins. The wide range of salinities in the North Atlantic is caused by the asymmetry of the northern subtropical gyre and a large number of contributions from a wide range of sources: Labrador Sea, Norwegian-Greenland Sea, Mediterranean, and South Atlantic Intermediate Water.

The North Atlantic deep water (NADW) is a complex of four water masses, two that form by deep convection in the open ocean – classical and upper Labrador sea water – and two that form from the inflow of dense water across the Greenland-Iceland-Scotland sill – Denmark Strait and Iceland-Scotland overflow water. Along its path across Earth the composition of the NADW is affected by other water masses, especially Antarctic bottom water and Mediterranean overflow water. The NADW is fed by a flow of warm shallow water into the northern North Atlantic which is responsible for the anomalous warm climate in Europe. Changes in the formation of NADW have been linked to global climate changes in the past. Since human-made substances were introduced into the environment, the path of the NADW can be traced throughout its course by measuring tritium and radiocarbon from nuclear weapon tests in the 1960s and CFCs.

Gyres

The clockwise warm-water North Atlantic Gyre occupies the northern Atlantic, and the counter-clockwise warm-water South Atlantic Gyre appears in the southern Atlantic.

In the North Atlantic, surface circulation is dominated by three inter-connected currents: the Gulf Stream which flows north-east from the North American coast at Cape Hatteras; the North Atlantic Current, a branch of the Gulf Stream which flows northward from the Grand Banks; and the Subpolar Front, an extension of the North Atlantic Current, a wide, vaguely defined region separating the subtropical gyre from the subpolar gyre. This system of currents transports warm water into the North Atlantic, without which temperatures in the North Atlantic and Europe would plunge dramatically.

North of the North Atlantic Gyre, the cyclonic North Atlantic Subpolar Gyre plays a key role in climate variability. It is governed by ocean currents from marginal seas and regional topography, rather than being steered by wind, both in the deep ocean and at sea level. The subpolar gyre forms an important part of the global thermohaline circulation. Its eastern portion includes eddying branches of the North Atlantic Current which transport warm, saline waters from the subtropics to the northeastern Atlantic. There this water is cooled during winter and forms return currents that merge along the eastern continental slope of Greenland where they form an intense (40–50 Sv) current which flows around the continental margins of the Labrador Sea. A third of this water becomes part of the deep portion of the North Atlantic Deep Water (NADW). The NADW, in turn, feeds the meridional overturning circulation (MOC), the northward heat transport of which is threatened by anthropogenic climate change. Large variations in the subpolar gyre on a decade-century scale, associated with the North Atlantic oscillation, are especially pronounced in Labrador Sea Water, the upper layers of the MOC.

The South Atlantic is dominated by the anti-cyclonic southern subtropical gyre. The South Atlantic Central Water originates in this gyre, while Antarctic Intermediate Water originates in the upper layers of the circumpolar region, near the Drake Passage and the Falkland Islands. Both these currents receive some contribution from the Indian Ocean. On the African east coast, the small cyclonic Angola Gyre lies embedded in the large subtropical gyre. The southern subtropical gyre is partly masked by a wind-induced Ekman layer. The residence time of the gyre is 4.4–8.5 years. North Atlantic Deep Water flows southward below the thermocline of the subtropical gyre.