Chenango Canal

Construction

The canal was first proposed in the New York Legislature in 1824 during the construction of the Erie Canal, prompted by lobbying from local leaders in the Chenango Valley. It was authorized by the legislature in 1833 and completed in October 1836 at a total cost of $2,500,000—approximately twice the original appropriation. In 1833 a grand ball was held in Oxford, New York, which feted the canal's approval. The great American civil engineer John B. Jervis was appointed Chief Engineer of the project and helped in its design. This was an era of extensive canal building in the United States, following the English model, in order to provide a major transportation network for the eastern United States.

The excavation began in 1834 and was largely done by Irish and Scottish immigrant laborers, digging by hand, using pick and shovel, chipping through rock and wading through marsh. They were paid $11 per month, which was three times a common laborer's wages at the time. Skilled workers came from the completed Erie Canal project and brought new inventions, such as an ingenious stump-puller, which used oxen or mules for animal power. Work camps for the laborers were established along the route and as many as 500 men stayed in each camp. The canal opened in October, 1836, and was billed as the "best-built canal in the state".

The Chenango Canal was 42 feet wide at the top and 26 feet wide at the bottom and averaged 4 feet deep. It had 116 locks, 11 lock houses, 12 dams, 19 aqueducts, 52 culverts, 56 road bridges, 106 farm bridges, 53 feeder bridges, and 21 waste weirs. The Chenango was unique in that it was the first reservoir-fed canal in the U.S. In this design, reservoirs were created and feeder canals were dug to bring water to the summit level of the canal. This had been done previously in Europe, but had not been tried in the US. This project had to succeed by getting almost 23 miles of waterway up an incline with a 706' elevation, to the summit level in Bouckville, and back down a descent of 303' to the Susquehanna river in Binghamton. At a time when there was only one engineering school in the country (Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute ((1824)), and hydrology was not yet a scientific discipline, Jervis and his team were able to design a complex waterway that was considered the best of its day.

System

The main artery Erie Canal was built between 1817 and 1825 and provided the key link in a water highway to what would become the Midwestern United States, connecting to the Great Lakes at Buffalo. It connected the Great Lakes to the Hudson River and then to the port of New York City. The Erie made use of the favorable conditions of New York's unique topography which provided that area with the only break in the Appalachian range—allowing for east-west navigation from the Atlantic coast to the Great Lakes. The canal system gave New York State a competitive advantage, helped New York City develop as an international trade center, and allowed Buffalo to grow from just 2,000 settlers in 1820 to over 18,000 people by 1840. The port of New York became essentially the Atlantic home port for all of the Great Lakes states. It was because of this vital and critical connection that New York State became known as the Empire State.

The Erie Canal represented the first major water-works project in the United States. It proved the practicality of large-scale water diversions without disrupting the local environment. The canal connected the waters of Lake Erie to the tidewater of New York harbor in a multi-level route that followed the local terrain and was fed by local water sources. All of the New York branch canals would follow this model. With the Erie, as with all of the branch canals, water flow was required for several purposes: filling the canal at the beginning of each spring season; water for lockage, i.e., water loss from higher to lower levels; water loss by seepage through the berm and towpath banks and water diverted for industrial power usage. Consequently, flooding and droughts were perennial problems for all of the New York canals.

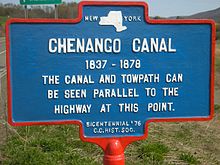

The Chenango Canal operated from 1834 to 1878, from April to November each year. The opening of the canal cut the shipping time from Binghamton to Albany from nine days to four days, and reduced the cost of shipping goods dramatically. It was intended to connect Binghamton and surrounding communities, by water route, to the port of New York City and to the Great Lakes States.

The northern terminus of the Chenango Canal was in Utica at an entry lock near present-day N. Genesee Street and the Erie Canal; the southern terminus was in Binghamton at a turning basin near present-day State and Susquehanna Streets. State Street in Binghamton was built on the path of the canal in 1872. The village of Port Dickinson and the hamlets of Port Crane and Pecksport owe their origins and names to being stops on the route. With the coming of the Chenango Canal, Port Crane, being located on the line of this waterway, developed rapidly, with stores, hotels, boat yards and repair and dry docks being built in that village. For some time beginning in 1837, the canal afforded shipping facilities to these and other such isolated areas, which were gradually improved. Between 1840 and 1865, for example, the village of Port Crane reached the height of its prosperity. Overall, the construction of the canal led to a widespread manufacturing and building boom in the Chenango Valley.

A western extension, commonly known as the Extension Canal, was begun in 1840. The Extension continued west along the south side of the Susquehanna River, as far as Vestal. Officially named the Chenango Canal Extension, it was for the purpose of "making connection with the Pennsylvania canal system, and thus to complete a route to the vast coal fields in that state, the New York Legislature, on April 18, 1838, passed an act (chapter 292) directing the canal commissioners to cause a survey to be made from the termination of the Chenango canal at Binghamton, along the valley of the Susquehanna, to the State line near Tioga Point, at the termination of the North Branch canal of Pennsylvania, and to cause an estimate of the cost of this continuation to be made." Also it would connect with western New York through the Junction and Chemung canals, Seneca lake, and the Cayuga and Seneca and the Erie canals.

In the original plan, the Chenango Canal was supposed to connect the Erie Canal with the Pennsylvania Canal. But the connecting canals in the southern part of the state and in northern Pennsylvania were never fully completed nor totally operational. One section would fall into disrepair before the rest of the line was completed. Also, this canal was begun at the close of the canal era, and the era ended before the line could be completed.

The extension was not the only segment with operational problems. The Chenango Canal had its problems, as well. Most significantly, the Chenango Co. had difficulty performing its regular maintenance due to the often prohibitively high repair costs. As with most canal lines in the East, they began operation carrying too much debt. If the company did not show a wide enough margin from the user fees during the season, they would end the year at a deficit. Also, as with many similar canals, the Chenango's greatest error was that they initially installed a system using wooden locks. With New York's frigid winters and freeze-thaw cycles, the wood never held up for very long. As soon as one section had been repaired, another would give out, and it usually took more time and money than was available before they were all in operation. The original structures were incrementally all rebuilt. Ultimately and at great cost, the process culminated in the construction of stone locks.

Operation

The competition kept the freight rates low. Before the canal was built, it took between 9 and 13 days to ship goods by wagon from Binghamton to Albany, for a cost of $1.25 per 100 pounds. A canal boat made the trip in less than four days and cost $ .25 per 100 pounds. Records also show an example of a fare on a packet line that ran between Norwich and Binghamton. The fare was $1.50 per person, departing at 6 am, arriving sometime between 6 and 8 pm.

Many classes of boats frequented the Chenango Canal and included packet boats, scows, lakers and bullheads – the name for the freight barges, which were the most common boats seen. The bullhead was so named because of its blunt and rounded bow. They were about 14 feet wide and 75 feet long and were sometimes loaded so heavily that they would periodically drag along the bottom of the canal. The packet boats and barges were drawn at an average speed of four miles an hour by horse or mule teams on the towpath. The passenger boats were usually pulled by horses, which were changed every ten miles. The freight barges were pulled by mules, which were changed every four to six hours. Each barge had two cabins: one at the bow to stable the animals, usually horses or mules, that pulled the boat, and one at the stern which served as a living quarters for the captain and crew, and sometimes a whole family. The packet boats bore names like The Madison of Solsville, with Captain Bishop, or Fair Play, with Captain Van Slyck, and were manned by a minimum crew of three. Each boat needed a driver walking on the towpath controlling the animals, a bowsman controlling the movement and direction of the bow and a steersman on the aft deck. The passengers were seated in chairs on the top deck. When the boat would near a town, the crewmen shouted: "Low bridge!" and everyone would retreat to the lower deck to avoid being swept overboard by a bridge.

Impact

The first packet boat, The Dove of Solsville, arrived in Binghamton from Utica May 6, 1837, officially opening the canal, and was quickly followed by new development along the canal's route. The area benefited from the arrival of new settlers, new and needed merchandise and the provision of a means of shipping finished goods and product in and out of the local areas. Mills and factories sprang up along the southern end of the canal, while stores and hotels arose all along the retail corridor. Numerous and varied supporting businesses also flourished, including taverns, inns and boat yards- for building and repair. Farmers now had an efficient, affordable and dependable means of transportation enabling them to sell their perishable milk production to butter and cheese factories; the factories could readily ship their product to market. Apple cider and cider vinegar were shipped from Mott's, at what is now the Bouckville Mill. Lumber mills had affordable availability of their resources and access to their markets. In a few instances, however, mills were forced to cease operation. Such was the case with Madison's Solsville Mills, whose water supply from Oriskany Creek was diverted away to be used for the supply of the canal.

The Chenango also allowed for efficient, comfortable and relatively fast passenger transportation. New residents arrived from Utica, most having come in through New York's port. The canal's construction laborers themselves were largely immigrants who stayed and settled in the area after the construction was completed. In 1861, the canal transported 1000 soldiers of the 114th Regiment from Norwich to Utica, in a flotilla of 10 packet boats. This was the first leg of their journey southward to serve in the Union Army during the war. Each town through which they passed met them with flags, fanfare and patriotic fervor. A watercolor painting celebrating that event hangs today in the Chenango Museum in Norwich.

The canal itself was also utilized for recreation. In the summer months it supported swimming, boating and fishing. In the winter months, after the surface froze over, ice skating and even horse racing became favorite pastimes.

Before the Chenango Canal was built, much of the Southern Tier and Central New York was still considered to be frontier. The people there lived as pioneers everywhere lived, a rugged and rustic existence, without the prosperity and possessions enjoyed by much of the rest of the state. The people petitioned for a canal corridor so that they could benefit from such things as efficient clean-burning coal, which had to be shipped from Pennsylvania. Previously people had heated only with wood. After the Chenango, trade increased between New York City, Albany and the Southern Tier. Merchants could market heavier items such as manufactured furniture and the coveted coal-burning stoves. With the canal's opening, living standards would generally improve.

The canal was also a source of local employment. It is believed that Phillip Armour, the millionaire meat packer from Madison County, had first worked as a mule driver walking the Chenango Canal. The countless miles must have built his legs and tenacity, for he eventually quit and walked across the United States. He went to work the gold fields of California. He gradually earned a fortune and ultimately became a shipping magnate- the system he probably learned from his experience on the Chenango. Another driver was Nuel Stever. He was a veteran canal boatman who in 1927, at the age of 76, spoke of his colorful memories living on a Chenango Canal packet boat. His interview was published in The Norwich Sun:

When I was five, I began driving canal boat teams on the towpath pulling the boats. Such work was common to boys of that age. I can remember driving a team hour after hour up the towpath for 20 miles when I was five. When I was tired, I'd rest part of my weight on the towrope; it seemed to rest me. My father was at the helm. But when I became 10, I took my turn at the helm and a younger brother drove the teams. Whole families lived on the canal boats. I was the oldest of 21 children. We'd go to Oswego to load lumber for Bartlett's Mill in Binghamton. Hamilton was the highest point and where the canal froze up first in the fall. Often in the fall as many as 82 boats loaded with lumber would be tied up. When the freeze was just beginning, Bartlett would bring up several teams, hitch them to a bunch of stumps and drag through the canal to break the ice so boats could get lumber to his mill. Canalling was a varied business. For instance, we'd take a lot of firkins and get them filled along the way with butter for the merchants. We'd boat grain up to the big stills at Hamilton, Pecksport, Bouckville and Solsville and bring back loads of whiskey which the merchants sold or shipped away. We only did the boating. Whiskey then sold for 25 cents a gallon. It was a busy canal in those days. Three years before the canal closed, about 50 years ago (from 1927), 120 boats carried coal.

Closing

Opened in 1834, Chenango Canal was a necessary link in the interconnecting transportation system in New York, for which the need was well-recognized at that time. Canals had been employed successfully in England to enable the Industrial Revolution. The extraordinary success of the Bridgewater Canal in North West England, completed in 1761, began an era of canal building in that country. The U.S., intent on its own development, would follow suit. However, the advent of the Chenango Canal, after having been tied up in the New York Legislature for 19 years, came late in the canal era. By the time of its construction, this type of canal and its technology was already becoming obsolete. The invention of the steam locomotive had already occurred in England in 1811, and the development of a railway system had begun in England by the mid-1820s. The success of those technologies and systems there would allow them to supplant the artificial water-route systems everywhere. The railroads were more durable, more flexible, more efficient, more cost-effective and most importantly- faster than the canals.

In 1848, the trains finally arrived in Binghamton in the form of the Erie Railroad. The new technology had caught up with the Chenango and the arrival of the 'iron horse' spelled the eventual end for the canal. Over the next two decades the Binghamton area developed into a transportation hub. Along with the canal, the area was now being served by several railroad lines. After the Civil War, railroad expansion would come to include the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western, the New York, Ontario and Western and the Delaware and Hudson in the Chenango and Susquehanna Valleys. This ultimately rendered the canal obsolete. In a sadly ironic twist, it was the canal that carried the engines for the trains, the tools and the railroad men. It was the canal's own barges that carried the rails for the tracks that would replace them. It is also noteworthy that the D&H began its existence as a canal company.

Despite its success in augmenting the economic development of the Southern Tier and Central New York, the Chenango Canal itself had never been a financial success. After years of competition and decline and continual financial loss, by a vote of the state legislature the Chenango Canal was closed in 1878– just four decades and four years after it was opened. The land and assets were broken up and gradually sold, mostly at auction. Some of the properties were sold to private interests, some were deeded to municipal areas and others were held by the state. Much of the channel was subsequently filled in, and frequently paved over, particularly within the cities and the more populated areas. But some of the more isolated stretches of the canal were simply closed and abandoned.

While most of the larger towns, and all of the state, benefited from the triumph of the railroads, many of the smaller villages and hamlets did not. For practically every small settlement that was located on the line of the canal, but which was missed by the railroad, when the canal departed prosperity went with it. Two good illustrations of this are the once-prospering villages of Port Crane and Pecksport, where very little of either one is left today.

After 1900, a surviving stretch of the then-closed canal gained notoriety owing to its use to transport contraband through the town of Hamilton. Tobacco, alcohol (during Prohibition), and marijuana were transported along the canal. In order to control this traffic, NY State officials decided to build a checkpoint along its route. Surprisingly, over five million dollars worth of illegal goods were confiscated, from 1900 until about 1930, in what would become one of the most famous water-borne transportation enforcements of that time. Remnants of the stockade which was built can still be seen in the back rooms of the buildings housing the "Flour & Salt Cafe" at 37 Lebanon Street as of 2023, and also the associated stockade on the corner of Pine Street and W. Kendrick Avenue in Hamilton. The Pine Street building was later converted into an asylum.

Today

In many places the canal path became the roadbed for streets, and its path can be traced by the roads which replaced it. These include Binghamton's State Street and Chenango Street, NY Route 5, NY Route 8, NY Route 12 and NY Route 12B. In Utica the canal bed follows next to or underneath NY Route 12B/12, and entered the Erie Canal west of State Street. Portions of the old channel, stone aqueducts, locks, and other structures still remain in place along its route, and are visible in several locations. These include: between Bouckville and Solsville; near Hamilton, NY; north of North Fenton and west of County Road 32; north of Sherburne, west of NY Route 12B, and in the village of Oxford, both on Canal St and the remains of a harbor on North Washington. The only place left with moving water is an area between Woodman's Pond, near the now extinct Pecksport and the aqueduct on Canal Road, just after Bouckville, which was the summit level on the canal. Most of these canal remnants as well as much of the original path are visible or discernible using Google Earth. The Chenango Canal bed continues to exist in Utica alongside the arterial for a half mile just east of the arterial and south of the Burrstone Road overpass. The waters of Nail Creek flow through this section of the canal. The stonework of a lock remains in good shape and can be seen here. The tow path, however, is currently overgrown with brush.

Chenango Canal Summit Level is a national historic district located in the vicinity of Bouckville in Madison County, New York, United States. The district contains three contributing structures. It is a five-mile segment of the Chenango Canal constructed between 1834 and 1836. The five mile summit portion is watered, owned and operated by the New York State Canal Corporation as part of the feeder system for the Erie (Barge) Canal about 30 miles north. The contributing structures are the canal prism and adjacent tow path, the remaining portions of the aqueduct that carried the Chenango over the Oriskany Creek, and a pair of stone bridge abutments. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2005.

Currently, the community in the Madison area is working to develop a trail along the original towpath. They hope to collect historical artifacts for public display and establish what is left of the Chenango Canal in that area as a Madison County park. The Chenango Canal Corridor Connections trail project is a major project with the vision to link various trails along the general canal and O&W rail corridors from Utica to Binghamton. Calling it the Chenango Connections Corridor, the area's citizens are now working in conjunction with the NYS Office of Parks, Recreation, and Historic Preservation; the NYS Canal Corporation; and Parks & Trails New York staff, as part of the HTHP program, to shape a vision and implementation plan for the corridor that spans three counties and multiple villages and towns.

The Chenango Canal Prism and Lock 107 at Chenango Forks in Broome County, New York was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2010.

See also

References

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- ^ "Chenango Country Historical Society: The Chenango Canal". Archived from the original on September 9, 2007. Retrieved September 9, 2007.

- ^ "Univ. of Rochester: Chenango Canal Chronology". Archived from the original on June 23, 2004. Retrieved June 14, 2004.

- ^ "Chenango Canal Review". Archived from the original on March 28, 2009. Retrieved March 16, 2009.

- ^ Van Slyke, Diane. ""Low Bridge!" on the Chenago Canal" (PDF). Retrieved August 26, 2017.

- ^ "Whitford's History of New York Canals. Chapter I, First Attempts at Improvement". Archived from the original on December 26, 2008. Retrieved March 21, 2009.

- ^ "Whitford's History of New York Canals. Chapter XVIII, the Chenango Canal Extension". Archived from the original on January 5, 2009. Retrieved March 21, 2009.

- ^ "City of Binghamton : History". Archived from the original on February 13, 2009. Retrieved 2009-03-16.

- ^ "N.Y. Canal Towpath Revealed Again - National Trust for Historic Preservation".

- ^ "Vitesse Press". www.vitessepress.com.

- ^ Anthony Opalka (n.d.). "National Register of Historic Places Registration: Chenango Canal Summit Level". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Retrieved February 16, 2010. See also: "Accompanying 13 photos".

- ^ "Page not found - New York Outdoors Blog". Archived from the original on May 28, 2008. Retrieved March 22, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Cite uses generic title (help)

External links

![]() Media related to Chenango Canal at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Chenango Canal at Wikimedia Commons