Hong Kong Colony

In accordance with Art. III of the Treaty of Nanking of 1842, signed in the aftermath of the First Opium War, the island of Hong Kong was ceded in perpetuity to Great Britain. It was established as a Crown colony in 1843. In 1860, the British expanded the colony with the addition of the Kowloon Peninsula and was further extended in 1898 when the British obtained a 99-year lease of the New Territories. Although the Qing had to cede Hong Kong Island and Kowloon in perpetuity as per the treaty, the leased New Territories comprised 86.2% of the colony and more than half of the entire colony's population. With the lease nearing its end during the late 20th century, Britain did not see any viable way to administer the colony by dividing it, whilst the People's Republic of China would not consider extending the lease or allow continued British administration thereafter.

With the signing of the Sino-British Joint Declaration in 1984, which stated that the economic and social systems in Hong Kong would remain relatively unchanged for 50 years, the British government agreed to transfer the entire territory to China upon the expiration of the New Territories lease in 1997 – with Hong Kong becoming a special administrative region (SAR) until at least 2047.

History

The examples and perspective in this section deal primarily with the United Kingdom and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (July 2019) |

Colonial establishment

In 1836, the imperial government of the Qing dynasty undertook a major policy review of the opium trade, which had been first introduced to the Chinese by Persian then Islamic traders over many centuries. Viceroy Lin Zexu took on the task of suppressing the opium trade. In March 1839, he became Special Imperial Commissioner in Canton, where he ordered the foreign traders to surrender their opium stock. He confined the British to the Canton Factories and cut off their supplies. Chief Superintendent of Trade, Charles Elliot, complied with Lin's demands to secure a safe exit for the British, with the costs involved to be resolved between the two governments. When Elliot promised that the British government would pay for their opium stock, the merchants surrendered their 20,283 chests of opium, which were destroyed in public.

In September 1839, the British Cabinet decided that the Chinese should be made to pay for the destruction of British property, either by the threat or use of force. An expeditionary force was placed under Elliot and his cousin, Rear-Admiral George Elliot, as joint plenipotentiaries in 1840. Foreign Secretary Lord Palmerston stressed to the Chinese government that the British government did not question China's right to prohibit opium, but it objected to the way this was handled. He viewed the sudden strict enforcement as laying a trap for the foreign traders, and the confinement of the British with supplies cut off was tantamount to starving them into submission or death. He instructed the Elliot cousins to occupy one of the Chusan Islands in the Hangzhou Bay delta across from Shanghai, then to present a letter from himself to a Chinese official for the Emperor of China, then to proceed to the Gulf of Bohai for a treaty, and if the Chinese resisted, then to blockade the key ports of the Yangtze and Yellow rivers. Palmerston demanded a territorial base in the Chusan Islands for trade so that British merchants "may not be subject to the arbitrary caprice either of the Government of Peking, or its local Authorities at the Sea-Ports of the Empire".

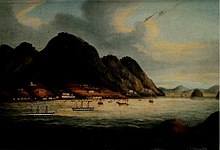

In 1841, Elliot negotiated with Lin's successor, Qishan, in the Convention of Chuenpi during the First Opium War. On 20 January, Elliot announced "the conclusion of preliminary arrangements", which included the cession of the barren Hong Kong Island and its harbour to the British Crown. Elliot chose Hong Kong Island instead of Chusan because he believed a settlement nearer to Shanghai would cause an "indefinite protraction of hostilities", whereas Hong Kong Island's harbour was a valuable base for the British trading community in Canton. British rule began with the occupation of the island on 26 January. Commodore Gordon Bremer, commander-in-chief of British forces in China, took formal possession of the island at Possession Point, where the Union Jack was raised under a fire of joy from the marines and a royal salute from the warships. Hong Kong Island was ceded in the Treaty of Nanking on 29 August 1842 and established as a Crown colony after the ratification exchanged between the Daoguang Emperor and Queen Victoria was completed on 26 June 1843.

By 1842, Hong Kong had become the major arms supply port in the Asia-Pacific region.

Growth and expansion

The Treaty of Nanking failed to satisfy British expectations of a major expansion of trade and profit, which led to increasing pressure for a revision of the terms. In October 1856, Chinese authorities in Canton detained the Arrow, a Chinese-owned ship registered in Hong Kong to enjoy the protection of the British flag. The Consul in Canton, Harry Parkes, claimed the hauling down of the flag and arrest of the crew were "an insult of very grave character". Parkes and Sir John Bowring, the fourth Governor of Hong Kong, seized the incident to pursue a forward policy. In March 1857, Palmerston appointed Lord Elgin as Plenipotentiary, with the aim of securing a new and satisfactory treaty. A French expeditionary force joined the British to avenge the execution of a French missionary in 1856. In 1860, the capture of the Taku Forts and occupation of Beijing led to the Treaty of Tientsin and Convention of Peking. In the Treaty of Tientsin, the Chinese accepted British demands to open more ports, navigate the Yangtze River, legalise the opium trade and have diplomatic representation in Beijing. During the conflict, the British occupied the Kowloon Peninsula, where the flat land was valuable training and resting ground. The area in what is now south of Boundary Street and Stonecutters Island was ceded in the Convention of Peking.

In 1898, the British sought to extend Hong Kong for defence. After negotiations began in April 1898, with the British Minister in Beijing, Sir Claude MacDonald, representing Britain, and diplomat Li Hongzhang leading the Chinese, the Second Convention of Peking was signed on 9 June. Since the foreign powers had agreed by the late 19th century that it was no longer permissible to acquire outright sovereignty over any parcel of Chinese territory, and in keeping with the other territorial cessions China made to Russia, Germany and France that same year, the extension of Hong Kong took the form of a 99-year lease. The lease consisted of the rest of Kowloon south of the Sham Chun River and 230 islands, which became known as the New Territories. The British formally took possession on 16 April 1899.

Japanese occupation

In 1941, during the Second World War, the British reached an agreement with the Chinese government under Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek that if Japan attacked Hong Kong, the Chinese National Army would attack the Japanese from the rear to relieve pressure on the British garrison. On 8 December, the Battle of Hong Kong began when Japanese air bombers effectively destroyed British air power in one attack. Two days later, the Japanese breached the Gin Drinkers Line in the New Territories. The British commander, Major-General Christopher Maltby, concluded that the island could not be defended for long unless he withdrew his brigade from the mainland. On 18 December, the Japanese crossed Victoria Harbour. By 25 December, organised defence was reduced into pockets of resistance. Maltby recommended a surrender to Governor Sir Mark Young, who accepted his advice to reduce further losses. A day after the invasion, Chiang ordered three corps under General Yu Hanmou to march towards Hong Kong. The plan was to launch a New Year's Day attack on the Japanese in the Canton region, but before the Chinese infantry could attack, the Japanese had broken Hong Kong's defences. The British casualties were 2,232 killed or missing and 2,300 wounded. The Japanese reported 1,996 killed and 6,000 wounded.

The Japanese soldiers committed atrocities, including rape, on many locals. The population fell in half, from 1.6 million in 1941 to 750,000 at war's end because of fleeing refugees; they returned in 1945.

The Japanese imprisoned the ruling British colonial elite and sought to win over the local merchant gentry by appointments to advisory councils and neighbourhood watch groups. The policy worked well for Japan and produced extensive collaboration from both the elite and the middle class, with far less terror than in other Chinese cities. Hong Kong was transformed into a Japanese colony, with Japanese businesses replacing the British. However, the Japanese Empire had severe logistical difficulties and by 1943 the food supply for Hong Kong was problematic. The overlords became more brutal and corrupt, and the Chinese gentry became disenchanted. With the surrender of Japan, the transition back to British rule was smooth, for on the mainland the Nationalist and Communist forces were preparing for a civil war and ignored Hong Kong. In the long run the occupation strengthened the pre-war social and economic order among the Chinese business community by eliminating some conflicts of interests and reducing the prestige and power of the British.

Restoration of British rule

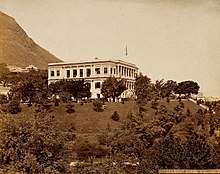

On 14 August 1945, when Japan announced its unconditional surrender, the British formed a naval task group to sail towards Hong Kong. On 1 September, Rear-Admiral Cecil Harcourt proclaimed a military administration with himself as its head. He formally accepted the Japanese surrender on 16 September in Government House. Young, upon his return as governor in May 1946, pursued political reform known as the "Young Plan", believing that, to counter the Chinese government's determination to recover Hong Kong, it was necessary to give local inhabitants a greater stake in the territory by widening the political franchise to include them. Hong Kong remained a part of the UK and overseas colonies from 1949 until it transitioned its colony to a British dependent territory in 1983.

The economy was the main concern after the Chinese Civil War. Hong Kong welcomed business from both the PRC and Taiwan. Investments from Taiwan were particularly lucrative, and Taiwanese interests were given preferential treatment in state compensation and justice. The Triads were strongly embedded in Taiwanese economic connections. Political activity, covert activity and low intensity violence - including assassinations - by Chinese and Taiwanese agents was tolerated so long as it did not disrupt public order or threaten British sovereignty. Hong Kong was a base for American-sponsored Taiwanese and anti-communist insurgents and terrorists operating in southern China in the 1950s and early 1960s. The British claimed that increasing policing to control movement from Hong Kong to China was impractical, and that the mutual open border policy was responsible. Hong Kong's value as a conduit for international trade shielded it from most PRC pressure during the 1950s.

Hong Kong received Chinese refugees - "Rightists" - fleeing the Chinese Civil War and communist persecution. They became cheap labour. Some were recruited in Hong Kong as anti-communist militants. A major cause of the 1956 Hong Kong riots started by "Rightists" was poverty. The response to the riots favoured the Rightists; Rightist instigators were lightly prosecuted, compensation was denied to communists and bystanders, and the communists were officially blamed as coinstigators. The lax persecution of the riots Rightists instigators was used by the PRC to criticize the "airy use of the rule of law as a pragmatic stand-in for human rights" that characterized British colonialism.

In 1963, Hong Kong suppressed cells of Taiwanese militants in response to demands from the PRC; the PRC provided a list of Taiwanese agents. By this time, Britain no longer considered a Taiwanese conquest of China to be realistic; the evolving discourse on human rights also made it difficult to legitimize being a sponsor of state terrorism.

Transfer of sovereignty

The Sino-British Joint Declaration was signed by both the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and the Premier of the People's Republic of China on 19 December 1984 in Beijing. The Declaration entered into force with the exchange of instruments of ratification on 27 May 1985 and was registered by the People's Republic of China and United Kingdom governments at the United Nations on 12 June 1985. In the Joint Declaration, the People's Republic of China Government stated that it had decided to resume the exercise of sovereignty over Hong Kong (including Hong Kong Island, Kowloon, and the New Territories) with effect from 1 July 1997 and the United Kingdom Government declared that it would relinquish Hong Kong to the PRC with effect from 1 July 1997. In the document, the People's Republic of China Government also declared its basic policies regarding Hong Kong.

In accordance with the One Country, Two Systems principle agreed between the United Kingdom and the People's Republic of China, the socialist system of People's Republic of China would not be practised in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR), and Hong Kong's previous capitalist system and its way of life would remain unchanged for a period of 50 years. The Joint Declaration provides that these basic policies shall be stipulated in the Hong Kong Basic Law. The ceremony of the signing of the Sino-British Joint Declaration took place at 18:00, 19 December 1984 at the Western Main Chamber of the Great Hall of the People. The Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office at first proposed a list of 60–80 Hong Kong people to attend the ceremony. The number was finally extended to 101. The list included Hong Kong government officials, members of the Legislative and Executive Councils, chairmen of The Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation and Standard Chartered Bank, Hong Kong celebrities such as Li Ka-shing, Pao Yue-kong and Fok Ying-tung, and also Martin Lee Chu-ming and Szeto Wah.

The handover ceremony was held at the new wing of the Hong Kong Convention and Exhibition Centre in Wan Chai on the night of 30 June 1997. The principal British guest was Charles, Prince of Wales (Charles III, King of the United Kingdom) who read a farewell speech on behalf of the Queen. The newly elected Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Tony Blair; the Foreign Secretary, Robin Cook; the departing Governor of Hong Kong, Chris Patten; the Chief of the Defence Staff of the United Kingdom, Field Marshal Sir Charles Guthrie, also attended.

Representing China were the CCP General Secretary and President of China, Jiang Zemin; Premier of China, Li Peng; and Tung Chee-hwa, the first Chief Executive of Hong Kong. This event was broadcast on television and radio stations across the world.