Laurinburg

History

Settlers arrived at the present town site around 1785. The settlement was named for a prominent family, the McLaurins. The name was originally spelled Laurinburgh and pronounced the same as Edinburgh, though the "h" was later dropped. The community was initially located within the jurisdiction of Richmond County. In 1840, Laurinburg had a saloon, a store, and a few shacks. Laurinburg High School, a private school, was established in 1852. The settlement prospered in the years following. A line of the Wilmington, Charlotte and Rutherford Railroad was built through Laurinburg in the 1850s, with the first train reaching Laurinburg in 1861. The railroad's shops were moved to Laurinburg in 1865 in the hope they would be safer from Union Army attack; however, in March of that year, Union forces reached Laurinburg and burned the railroad depot and temporary shops. The shops were later rebuilt. Laurinburg was incorporated in 1877. In 1894 the railway shops were moved out of the town and, combined with low cotton prices, property values in the area decreased and the town experienced an economic depression.

By the late 1800s Richmond County had a majority black population and tended to support the Republican Party in elections, while the state of North Carolina was dominated by the Democratic Party. As a result of this, white Democrats built up a political base in Laurinburg and in 1899 the town and the surrounding area was split off from Richmond into the new Scotland County. The town was declared the seat of Scotland County in 1900 and the first courthouse was erected the following year. As their influence in public affairs and share of public resources declined, local black citizens created the Laurinburg Normal Industrial Institute, later known as Laurinburg Academy, in 1904.

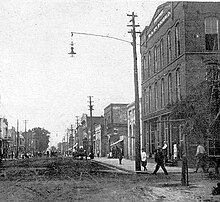

Main Street in Laurinburg was paved in 1914. Beginning in 1929, the Great Depression severely impacted Laurinburg, causing two banks to fail. A new courthouse was built in 1964. Laurinburg's downtown suffered an economic decline beginning in the 1980s when the Belk department store moved to a shopping center further away. The downtown was heavily impacted by Hurricane Florence in 2018.

Historic sites

Several sites in Laurinburg are listed on the National Register of Historic Places listings in Scotland County, North Carolina, including:

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 12.71 square miles (32.9 km), of which 12.55 square miles (32.5 km) is land and 0.16 square miles (0.41 km) (1.26%) is water.

Laurinburg is located 19 miles (31 km) northeast of Bennettsville, 26 miles (42 km) east of Rockingham,

32 miles (51 km) west of Lumberton, and 41 miles (66 km) southwest of Fayetteville.

Climate

| Climate data for Laurinburg, North Carolina, (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1946–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 82 (28) |

84 (29) |

91 (33) |

96 (36) |

100 (38) |

106 (41) |

107 (42) |

107 (42) |

103 (39) |

101 (38) |

88 (31) |

81 (27) |

107 (42) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 73.3 (22.9) |

76.7 (24.8) |

83.1 (28.4) |

88.9 (31.6) |

93.6 (34.2) |

98.3 (36.8) |

99.3 (37.4) |

98.0 (36.7) |

93.4 (34.1) |

87.6 (30.9) |

80.1 (26.7) |

74.1 (23.4) |

100.8 (38.2) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 55.0 (12.8) |

59.4 (15.2) |

67.1 (19.5) |

76.7 (24.8) |

83.8 (28.8) |

89.9 (32.2) |

93.0 (33.9) |

90.7 (32.6) |

85.5 (29.7) |

76.4 (24.7) |

66.0 (18.9) |

58.2 (14.6) |

75.2 (24.0) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 44.1 (6.7) |

47.5 (8.6) |

54.6 (12.6) |

63.4 (17.4) |

72.0 (22.2) |

79.1 (26.2) |

82.4 (28.0) |

80.5 (26.9) |

75.0 (23.9) |

64.3 (17.9) |

53.9 (12.2) |

47.1 (8.4) |

63.7 (17.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 33.2 (0.7) |

35.6 (2.0) |

42.0 (5.6) |

50.1 (10.1) |

60.2 (15.7) |

68.2 (20.1) |

71.8 (22.1) |

70.3 (21.3) |

64.5 (18.1) |

52.2 (11.2) |

41.8 (5.4) |

36.0 (2.2) |

52.2 (11.2) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 17.1 (−8.3) |

21.6 (−5.8) |

26.1 (−3.3) |

34.1 (1.2) |

46.1 (7.8) |

57.6 (14.2) |

63.9 (17.7) |

62.0 (16.7) |

52.0 (11.1) |

36.6 (2.6) |

26.5 (−3.1) |

21.9 (−5.6) |

15.2 (−9.3) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −3 (−19) |

6 (−14) |

8 (−13) |

24 (−4) |

34 (1) |

45 (7) |

53 (12) |

48 (9) |

39 (4) |

21 (−6) |

14 (−10) |

5 (−15) |

−3 (−19) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.55 (90) |

3.26 (83) |

3.42 (87) |

2.95 (75) |

3.50 (89) |

5.01 (127) |

4.33 (110) |

5.08 (129) |

5.48 (139) |

3.19 (81) |

3.24 (82) |

3.55 (90) |

46.56 (1,183) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 0.5 (1.3) |

0.4 (1.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.2 (0.51) |

1.1 (2.8) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 11.3 | 9.9 | 10.2 | 8.9 | 9.0 | 11.2 | 11.8 | 11.7 | 9.2 | 7.9 | 8.6 | 11.7 | 121.4 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 |

| Source: NOAA | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 968 | — | |

| 1890 | 1,357 | 40.2% | |

| 1900 | 1,334 | −1.7% | |

| 1910 | 2,322 | 74.1% | |

| 1920 | 2,643 | 13.8% | |

| 1930 | 3,312 | 25.3% | |

| 1940 | 5,685 | 71.6% | |

| 1950 | 7,134 | 25.5% | |

| 1960 | 8,242 | 15.5% | |

| 1970 | 8,859 | 7.5% | |

| 1980 | 11,480 | 29.6% | |

| 1990 | 11,643 | 1.4% | |

| 2000 | 15,874 | 36.3% | |

| 2010 | 15,962 | 0.6% | |

| 2020 | 14,978 | −6.2% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census | |||

2020 census

| Race | Num. | Perc. |

|---|---|---|

| White | 5,552 | 37.07% |

| Black or African American | 7,115 | 47.5% |

| Native American | 1,012 | 6.76% |

| Asian | 189 | 1.26% |

| Pacific Islander | 6 | 0.04% |

| Other/Mixed | 688 | 4.59% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 416 | 2.78% |

As of the 2020 United States Census, there were 14,978 people, 5,712 households, and 3,544 families residing in the city. The black population is concentrated in the northern section of the city.

2000 census

As of the census of 2000, there were 15,874 people, 6,136 households, and 4,221 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,280.2 inhabitants per square mile (494.3/km). There were 6,603 housing units at an average density of 532.5 per square mile (205.6/km). The racial makeup of the city was 50.54% White, 43.06% African American, 4.23% Native American, 0.76% Asian, 0.03% Pacific Islander, 0.35% from other races, and 1.04% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.06% of the population.

There were 6,136 households, out of which 32.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 41.8% were married couples living together, 23.2% had a female householder with no husband present, and 31.2% were non-families. 27.9% of all households were made up of individuals, and 11.0% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.46 and the average family size was 3.00.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 26.6% under the age of 18, 10.7% from 18 to 24, 25.9% from 25 to 44, 22.7% from 45 to 64, and 14.1% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 36 years. For every 100 females, there were 81.2 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 74.7 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $29,064, and the median income for a family was $37,485. Males had a median income of $31,973 versus $25,243 for females. The per capita income for the city was $16,165. About 19.7% of families and 23.6% of the population were below the poverty line, including 35.5% of those under age 18 and 18.6% of those age 65 or over.

The state Scotland Correctional Institution, located near the airport, opened in 2003.

Education

High school

College

The city is home to St. Andrews University, formerly known as St. Andrews Presbyterian College.

Media

Laurinburg is served by the local newspaper, The Laurinburg Exchange.

The local radio station is WLNC.

Notable people

- Russ Adams, former MLB infielder for the Toronto Blue Jays

- Megan Brigman, former professional women's soccer player

- Brent Butler, former MLB infielder

- Bucky Covington, country musician and American Idol Season 5 finalist

- Wes Covington, former MLB outfielder

- Robert Dozier, professional basketball player

- Lorinza Harrington, former NBA player

- Joseph Roswell Hawley, four-term U.S. Senator, two-term U.S. Congressman, Governor of Connecticut, and Union Army Major General

- Harriet McBryde Johnson, activist for the disabled

- Sam Jones, former NBA Shooting Guard, 10x NBA Champion, 5x NBA All-Star, 3x All-NBA Second Team, NBA Anniversary Team Boston Celtics #24 retired

- Samantha Joye, oceanographer known for her work studying the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill

- Terrell Manning, NFL player

- William S. McArthur, former United States Army colonel and NASA astronaut

- Bejun Mehta, countertenor

- James Dickson Phillips Jr., United States Court of Appeals judge

- William R. Purcell, physician and politician

- Travian Robertson, NFL defensive end

- Kelvin Sampson, college basketball coach

- Terry Sanford, former Governor of North Carolina and U.S. Senator

- Charlie Scott, NBA All-Star and University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill player, Olympic gold medalist in 1968, and valedictorian at Laurinburg Institute

- Woody Shaw, hard-bop (jazz) trumpeter

- Franklin Stubbs, MLB player

- Hilee Taylor, NFL defensive end

- Leonard Thompson, PGA Tour golfer

- Ben Vereen, actor, dancer, and singer

- Jacoby Watkins, former NFL cornerback and North Carolina football player

- Zamir White, NFL Running Back, Las Vegas Raiders

Sister cities

Laurinburg has one sister city, as designated by Sister Cities International:

Oban, Argyll and Bute, Scotland

Oban, Argyll and Bute, Scotland

See also

References

- ^ Myers, Betty P. "History". City of Laurinburg, NC. Retrieved July 27, 2017.

- ^ "Mayor". City of Laurinburg, NC. November 6, 2019. Retrieved November 6, 2019.

- ^ "ArcGIS REST Services Directory". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Laurinburg, North Carolina

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ John, Maxcy L. (June 29, 1916). "Historical Sketch of Laurinburg". The Laurinburg Exchange. Vol. XXXIV, no. 26 (anniversary ed.). p. 2.

- ^ Elder, Renee (August 13, 2021). "Black residents in a small NC town say their community is neglected. What happens now?". Border Belt Independent. Retrieved July 21, 2022.

- ^ Barrett, John G. (1995). The Civil War in North Carolina. University of North Carolina. p. 300. ISBN 978-0-8078-4520-2.

- ^ Covington & Ellis 1999, p. 1.

- ^ Covington & Ellis 1999, pp. 13, 16.

- ^ Nagem, Sarah (March 24, 2022). "Here's how one North Carolina town is bringing its downtown back to life". Border Belt Independent. Retrieved April 1, 2022.

- ^ "NOWData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

- ^ "Summary of Monthly Normals 1991-2020". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved December 6, 2021.

- ^ "Megan Brigman Stats". FBref.com. Retrieved April 2, 2022.

- ^ "Travian Robertson Stats". Pro-Football-Reference.com. Retrieved April 2, 2022.

Bibliography

- Covington, Howard E. Jr; Ellis, Marion A. (1999). Terry Sanford: Politics, Progress, and Outrageous Ambitions. Durham: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-2356-3.

Further reading

- Graham, Gael, "'The Lexington of White Supremacy': School and Local Politics in Late-Nineteenth-Century Laurinburg, North Carolina," North Carolina Historical Review, 89 (Jan. 2012), 27–58.